Dutch-Portuguese War

The Dutch-Portuguese War was a colonial war between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Republic of the United Netherlands that ran from 1624 to 1661. The main fighting took place in South America and Africa . The conflict ended without a clear winner.

prehistory

With the death of Henry I (1512–1580), the ruling family of the Avis died out in the Kingdom of Portugal . As his successor, the Portuguese Cortes elected Philip II of Spain (1527-1598) in 1581 , who now ruled both empires in personal union (in Portugal as Philip I ). However, Portugal was thus also involved in the wars of the Kingdom of Spain against England and the United Provinces of the Netherlands ( → Eighty Years War ). Already during the failed attempt to invade England in 1588, most of the Portuguese fleet was drawn into the defeat of the great Spanish Armada and from then on was no longer available to protect the Portuguese overseas holdings.

The disadvantages of the Spanish War for the Portuguese state soon became apparent. In 1594, King Philip II closed the port of Lisbon to English and Dutch ships. The following year, English naval units raided the port city of Faro, and English pirate activities against Portuguese India soon began . From the year 1600 the newly founded British East India Company began to seize the Portuguese bases in the Far East . In 1622 she supported the Arabs in conquering the Ormuz base . The Dutch conquered Malacca from the Portuguese in 1601 and founded their own East India company the following year , which competed with the Portuguese trade in India . A few years later, a Danish , a Swedish and a French company followed, to the disadvantage of Portugal .

This development turned out to be particularly sustainable in South America . As early as 1593 and 1604, English and Dutch privateers raided the Portuguese cities in the colony of Brazil . However, the Dutch West India Company , founded in 1621, soon began a colonial expansion in the Atlantic region , which marked the beginning of a real war.

Course of war

The Netherlands on the offensive (1624-1640)

In 1624 a fleet of the company under the command of Jacob Willekens and Piet Pieterszoon Heyn conquered the city of Bahia from the Portuguese with 26 ships . Then she turned to Africa to conquer the Portuguese city of Luando , which failed, however. But the following year, on April 30, the city was recaptured by a Spanish-Portuguese expedition. After a second attempt at conquest failed in 1627, the Dutch turned against Pernambuco , the main production area for sugar and wood. Admiral Loneq conquered the city of Olinda in 1630 and thus laid the foundation stone for the colony of Dutch Brazil , whose capital soon became Recife . In the next few years there were changeful battles against the Portuguese settlers under the generals Matias de Albuquerque and Bagnuolo, as well as against Spanish-Portuguese naval units. The colony received hardly any support from the motherland. Nevertheless, the Dutch initially prevailed. By 1636 they hijacked around 700 ships, the value of which was around 100,000 guilders. But this could not cover the company's war costs.

In order to make the colony more independent and thus save money, Johann Moritz von Nassau-Siegen (1604–1679) was appointed governor of New Holland on August 4, 1636 and sent to the new colony. Technicians, scholars and fresh troops also arrived there with him on January 23, 1637, who made it possible to build up their own state system. Moritz von Nassau-Siegen consolidated the colony and expanded it to the northeast. Until 1642 the West Indian colony maintained garrisons in Maranhão , Ceará , Rio Grande do Norte , Paraíba , Itamaracá , Pernambuco , Alagoas and Sergipe . Although Moritz von Nassau-Siegen never had more than 6000 men, he tried in vain to take Bahia in 1638, but the following year he managed to repel a Portuguese attack on Refice. A decisive battle took place from January 12th to 17th, 1640 in the naval battle of Itamaracá , in which the Dutch fleet achieved a clear victory over the Spanish-Portuguese fleet of Count La Torre.

Economically, Brazil was also closely linked to the Portuguese colonies on the West African coast, because it was from there that it obtained working slaves . It was therefore natural that the West India Company tried to conquer these bases as well. The previous attempts in 1603, 1606 and 1607 to take Fort Elmina on the coast of Guinea had failed. Piet Heyn's venture also failed in 1624 and Jan Dirickszon's last attempt to take the fortress with 15 ships and 1200 soldiers in the Battle of Elmina in 1625 was foiled by the Portuguese governor Francisco de Sotomaior. In 1637 Moritz von Nassau-Siegen sent another expedition (9 ships; approx. 800 soldiers) against Elmina and captured the strategic base.

The Armistice Period (1641-1648)

In December 1640 there was an overthrow in Portugal. The Portuguese nobility declared themselves independent from Spain and elected John IV (1604–1656) from the House of Braganza as the new king. On the one hand, the Portuguese colonies lost the support of Spanish military power, but on the other hand, the United Netherlands had to be interested in an end to the costly war. The order was issued to all subjects of the States General not to undertake any more acts of war against Portugal, at least in Europe. In 1641 negotiations took place in The Hague . The Portuguese ambassador wanted to conclude an armistice, while the restitution of Portuguese colonial property (in return for high severance payments) and an alliance against Spain should continue to be negotiated. The Dutch trading companies, on the other hand, were interested in an immediate peace agreement that would secure their property, or at least a peace limited to Europe that would relieve their finances. Nevertheless, the governor of the United Netherlands, Prince Friedrich Heinrich (1584–1647), accepted the Portuguese offer of an armistice. This immediately led to relaxation in Brazil, where prisoners were exchanged for the first time and the Portuguese guerrillas were withdrawn from New Holland. However, both sides hesitated to ratify the armistice in order to gain some advantage. Moritz von Nassau-Siegen sent another expedition to Africa, which took the cities of Luanda and Benguela as well as the islands of São Tomé and Annobón in Portuguese Angola in 1641 . On the Gold Coast she also conquered Adras , Minas and Calabares . With this step he pursued two goals: firstly, the West India Company wanted to get its own slave source and at the same time damage the Spanish-Portuguese economy. Only then was the armistice respected in practice.

But shortly afterwards, in 1642, an uprising against Dutch rule broke out in Maranhão. It quickly took on larger proportions without Moritz von Nassau-Siegen having the means to fight it effectively. As a result of the armistice agreement, the share prices of the West India Company, which could no longer count on the prizes from the pirate trips, had fallen. Accordingly, the subsidies for the New Holland colony had also been lowered. Under these circumstances, Moritz von Nassau-Siegen asked for his release in frustration and left the continent in May 1644. The government was then taken over by a civil-military council. Only a few months later, another uprising against the Dutch government broke out in Pernambuco under the leadership of the mulatto João Fernandes Vieira. The Portuguese administration in Bahia initially held back and did not help the insurgents. It was only when Vieiras guerrillas near Tabocas (15 kilometers from Recife) were able to record a military success against the Dutch troops and subsequently controlled the entire country with the exception of the cities that Governor General Telles da Silva decided to set up two regiments . Officially, they were supposed to come to the aid of the Dutch, but in fact they were intended to support the insurgents. When these regiments intervened, the situation of the Dutch became increasingly critical.

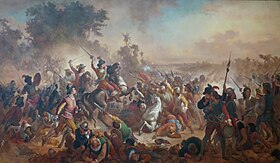

In 1648 the war flared up again completely. Initially, two attempts by the Dutch troops against Bahia and the Rio São Francisco failed. Then the Indian auxiliary troops defected to the Portuguese and on April 19, seven Dutch regiments (approx. 4,500 men) under Lieutenant General Siegmundt von Schkoppe at Guararapes (south of Recife) suffered a heavy defeat against only 2,400 Portuguese under the combined command of Fernandes Vieira , Vidal de Negreiros, Felipe Camarão and Henrique Dias, who were holed up on a hill. After this victory, Olinda fell into Portuguese hands. The Portuguese seized the opportunity and started an expedition to the west coast of Africa, where they recaptured the lost bases with minimal effort. According to the historian William C. Atkinson, this operation was the preliminary decision of the war. Control of the slave trade greatly improved the Portuguese position in South America, while the Dutch suffered a severe economic blow.

The Portuguese Offensive (1649–1661)

Only now did the Portuguese crown begin the war against the Netherlands again. Her means for this were limited, as she was in a war of independence against Spain ( → War of Restoration ). This conflict required the greatest financial outlay to be directed towards the Iberian Peninsula and the fleet also consisted of only a few ships. Therefore the Portuguese government decided to set up a trading company, which should maintain economic and military traffic with the colonies. By decree of the Portuguese King John IV , the General Society of the Brazilian Trade (Port .: Companhia Geral do Comércio do Brasil) was founded on March 10, 1649 . It was based in Lisbon and was legally obliged to maintain 36 ships and protect the trade routes. They largely fulfilled this task and brought important armaments to South America.

On February 19, 1649 there was the second battle at Guararapes. This time the Dutch defended the hills, but were trapped and wiped out by a Portuguese overwhelming force. About 1000 Dutch fell in the battle against 47 Portuguese, as well as 60 Indians and blacks. The war dragged on for the next few years without any results. The Dutch defended their permanent positions and were gradually pushed back. From 1652 their situation had become hopeless. In Europe, the United Netherlands became involved in a war against the Commonwealth of England ( → Anglo-Dutch War (1652–1654) ), which tied up all forces. At the end of 1653 only Recife remained. When Johann IV sent a fleet to cut off the Dutch colony from the sea, the garrison had to capitulate on January 26, 1654. All of New Holland was again in Portuguese possession.

The forms of colonial war

The conduct of war in Brazil differed significantly from the forms common in Europe at the time. The Portuguese residents in particular pursued guerrilla tactics, the most striking element of which was the ambush. Prisoners were treated ruthlessly, which led to violent protests by the Dutch colonial administration under Prince Johann Moritz. In return, they threatened reprisals against the civilian population. The Portuguese often treated the Dutch as pirates and accused them of allying themselves with “man-eating” Tapuja Indians. In fact, the Indians tended to massacre their enemies on their own initiative.

The regular military of the Dutch West India Company consisted mainly of undisciplined and often poorly cared for soldiers from a wide variety of nations: Dutch, German, French, English and Poles. Often they were mercenaries, but in other cases they were settlers who were promised land for their military service. The Portuguese armed forces were also very heterogeneous: Allied Indians, evangelized Indians, black slaves recruited from the plantations, mongrel units from the border regions, a corps made up of Neapolitans, Spaniards and Portuguese, and finally the militia-like formations of the Portuguese settlers. The troops were qualitatively inferior to the Dutch associations and were often armed only with agricultural tools such as machetes and pitchforks. The slaves and allied Indians proved to be particularly unreliable in the course of the war. Many changed camps, even several times, depending on the war situation.

Peace treaty and consequences

In 1657 the Dutch first attacked the Portuguese mainland and blocked Lisbon for three months. Before the final peace agreement between the two powers, Portugal lost practically all of its possessions in East Asia. Ceylon fell in 1655 , and in 1663, after a first peace treaty in August 1661, Malabar was lost. Only Portuguese India , Macau , Timor and a few other possessions on the Lesser Sunda Islands remained Portuguese. However, in the final peace agreement in 1663, Portugal continued to claim the coasts of Brazil and West Africa, although it had to pay monetary compensation to the United Netherlands.

According to the historian Jaime Cortesão, the common struggle of Indians, slaves and Portuguese settlers created a “Brazilian sense of community” for the first time , while the denominational component of the conflict gave the war the character of a crusade.

After the loss of East Indian colonies and the decline in the East India trade, Brazil developed into the most important and above all most profitable colonial property in Portugal. The cane sugar grown there with the help of African slaves and, from the beginning of the 18th century, especially gold and diamonds became the basis of Portugal's wealth.

Remarks

- ^ Ernst Gerhard Jacob: Principles of the History of Portugal and its Overseas Provinces , Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1969, p. 110f

- ^ Ernst Gerhard Jacob: Principles of the history of Portugal and its overseas provinces , Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1969, p. 111

- ^ Ernst Gerhard Jacob: Fundamentals of the history of Portugal and its overseas provinces , Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1969, p. 112

- ↑ Walther L. Bernecker / Horst Pietschmann / Rüdiger Zoller: Eine kleine Geschichte Brasiliens , Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt / Main 2000, p. 75

- ^ A b Johann Moritz (Nassau-Siegen). In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Vol. 14, p. 270

- ^ Ernst Gerhard Jacob: Fundamentals of the history of Portugal and its overseas provinces , Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1969, p. 114

- ↑ Walther L. Bernecker / Horst Pietschmann / Rüdiger Zoller: A Little History of Brazil , Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt / Main 2000, p. 76

- ^ A b William C. Atkinson: History of Spain and Portugal , Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, Munich 1962, p. 228

- ↑ Walther L. Bernecker / Horst Pietschmann / Rüdiger Zoller: A Little History of Brazil , Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt / Main 2000, p. 79f

- ^ A b Eduardo Bueno: Brasil - Uma Historia , São Paulo 2003

- ↑ Walther L. Bernecker / Horst Pietschmann / Rüdiger Zoller: A Little History of Brazil , Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt / Main 2000, p. 85f

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, the following statements are based on: Walther L. Bernecker / Horst Pietschmann / Rüdiger Zoller: Eine kleine Geschichte Brasiliens , Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt / Main 2000, pp. 76-78

- ^ AH Oliveira Marques: History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire , Alfred Kröner Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, p. 239

- ^ Ernst Gerhard Jacob: Fundamentals of the history of Portugal and its overseas provinces , Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1969, p. 122

- ^ Jaime Cortesão: Dois Centenários. In: Ocidente (1954), p. 57

literature

- Walter G. Armando: History of Portugal . W. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 1966.

- William C. Atkinson: History of Spain and Portugal . Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, Munich 1962.

- Walther L. Bernecker et al. a .: A little history of Brazil . Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt / M. 2006, ISBN 3-518-12150-2 .

- Ernst G. Jacob: Basic features of the history of Portugal and its overseas provinces . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1969.

- António Henrique de Oliveira Marques : History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 385). Translated from the Portuguese by Michael von Killisch-Horn. Kröner, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-520-38501-5 .