Panagia Episkopi

| Panagia Episkopi (Παναγία Επισκοπή) | ||

|---|---|---|

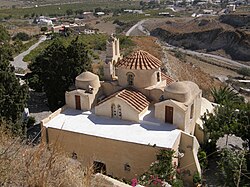

West side of the church |

||

| Data | ||

| place | Mesa Gonia , Santorini | |

| Construction year | 11./12. century | |

| Coordinates | 36 ° 22 '39 " N , 25 ° 27' 51" E | |

|

|

||

The Panagia Episkopi ( Greek Παναγία Επισκοπή ) is the former bishop's church on the Greek Cycladic island of Santorin (Thira) , which dates back to the Middle Byzantine period . It is also called Panagia tis Episkopis (Παναγία της Επισκοπής) or Naos Episkopis Thiras (Ναός Επισκοπής Θήρας). According to an inscription that has survived and has now been almost completely destroyed, the church building was donated by Emperor Alexios I Komnenos and replaced the previous building of a three-aisled early Byzantine basilica at the end of the 11th and beginning of the 12th century . The church is consecrated to Panagia ('All Saints'), a Greek Orthodox name for the Virgin Mary , the name suffix Episkopi means ' episcopal '. The Panagia Episkopi was the seat of the Orthodox diocese on Santorini until 1207 and from 1537 to 1827 .

location

The church was built on the northern foothills of the Profitis Ilias (Προφήτης Ηλίας), the highest point in Santorini with 567 meters. It stands on a hill about 600 meters southeast of the village of Mesa Gonia (Μέσα Γωνιά), which is also known as Episkopi Gonias (Επισκοπή Γωνιάς) after the former bishopric. The east coast of the island at Kamari (Καμάρι) is about two kilometers away from the Panagia Episkopi , the island capital Fira (Φηρά) is five kilometers northwest of the church. A partially paved road connects Mesa Gonia with Panagia Episkopi , in front of which there is a parking lot directly to the north.

description

Building

The Panagia Episkopi is a beige-washed cross- domed church with extensions. The central structure of the floor plan of a Greek cross with 14 meters in length and a maximum width of 11.10 meters by means of carrying a spool on the crossing patch dome in the middle of the structure. The roofs of the church with red bricks covered or simply plastered. The building has a total of five entrances, two in the south and two in the north and the main entrance in the west.

The east-facing cross arm of the church with the altar has a semicircular apse that is also recognizable in the exterior . A coupled triple window is set into this, which, like two smaller windows next to the apse, was walled up with colored glass stones . The red, green, yellow and blue glass stones are the only external light inlet of the chancel, which is otherwise only further illuminated from the interior of the church through the open doors of the iconostasis or over them. To the north of the chancel, on the northeast side of the building, there is a narrow bell carrier. In it hang four bells that can be operated on ropes from the outside.

On the flat roof of the western extension, accessible through a narrow staircase on the south side, there are two chapels. They were supplemented in the early 20th century through the entrance hall and to the Prophet Daniel and the Saint Gregory , the theologian consecrated.

|

|

|

|

| Entrance to the church grounds |

North-east side of the church with apse |

Triple window on the apse |

Entrance hall from the southwest |

Inside the Panagia Episkopi there are several larger and smaller rooms due to the additions, the church looks angled. The floor is laid out with marble slabs of different sizes. A relatively low synthronon is integrated in the apse . In front of the central church space is an entrance hall ( narthex ) in the west, which extends over the full width of the church. It originally had a side entrance from the north and south, in addition to the main entrance in the middle of the west wall. However, the southern part of the narthex was separated from the interior of the church and now represents a small side room that can only be reached from the outside through the southern entrance. In the south-east, the corner of the cross ground plan was filled with a separate room. It was added to resolve the dispute between Roman and Orthodox Christians in 1767 and a breakthrough to the chancel was added to serve as a chapel for the Roman Christians in the future.

Furnishing

Various icon stands are lined up on the walls of the interior. The best-known icon is that of Panagia Glykofilousa (Παναγιά Γλυκοφιλούσα 'Sweet Kissing Madonna '), which stands behind glass on the south side of the central church. The image, dated to the 12th century, is considered to be the most valuable icon of the church.

Iconostasis

The iconostasis , which separates the main room of the church in the east from the chancel called Bema in an Orthodox church , is characterized by a brilliant multicolored effect. It has the usual five-part structure. In the lower part it consists of the original furnishings from the construction period of the church around 1100. Above is a wooden architrave from the post-Byzantine period with carvings, a frieze with 14 icons and a carved top. The variety of ornaments is considered unique in the Middle Byzantine era, there are connections to the 6th century and to churches in Constantinople, Venice and Ravenna.

The central passage, known as the Holy Door, is closed with a double-winged, chest-high door. The wings consist of valuable wood carvings from the 17th century with floral motifs and two dragons at the top. They are each painted with an apostle, Peter on the left , Paul on the right .

At the side of the central gate there is a permanently installed field on the left and right. They consist of upright flat marble slabs and feature a rare marble inlay technique, in which geometric and floral patterns were carved into the marble as reliefs. The motifs come from the Arabic tradition and are complemented by small birds, swastikas, flowers, palmettes and leaves. The depressions in the reliefs were filled with an originally red, now darkened mass of wax and mastic . Using the same technique, marble inlays are also applied to the paneling of the columns, connecting panels and the door lintels. Two icons are set above it. On the left side of the door the Panagia with the baby Jesus is depicted, on the right of the central door Christ Pantocrator with the blessing right hand and in the left arm holding a closed gospel book . These two icons are modern creations, in their place were icons from the 17th century until a theft in 1982.

The north and south gates to the chancel outside the supporting columns are clad with head-high icons of the Archangel Gabriel (left) and Saint Menas (right). The icon of Menas is partially inlaid with silver work. The wooden tower was made by local artists in the 18th century. It shows an architrave with various motifs, including grapes and birds. A frieze is set into it, in which 14 icons from the life of Jesus can be found. The original icons from the 17th century showed the feasts of the lives of Christ and Mary. Here, too, modern icons from the life of Jesus replace those stolen in 1982.

The variety of decorations on the iconostasis can be interpreted as a reminder of the traditions of golden Constantinople. She tries to bring together elements of all styles there "with a certain nostalgia". This results in a kind of Neo- Justinianism , which is implemented in a specifically Greek form using the marble inlay technique.

Frescoes

(fresco in the chancel)

The interior of Panagia Episkopi was decorated with frescoes when it was built . They were covered with plaster in Ottoman times. Moisture destroyed most of them over the centuries. Some of the frescoes could be exposed and restored. The style of the figures in the pictures is reminiscent of wall paintings in Cappadocia , which is why the Greek building researcher and Byzantinist Anastasios Orlandos assumed an eastern origin for the artist. He dated the frescoes around 1100. The frescoes show various hierarchs , martyrs and saints as well as scenes from the life of Jesus and other biblical stories.

Among the scenic representations, the feast of Herod Boethos is outstanding. The fresco depicts the king on his throne pointing to his wife Herodias when she presents him with a bowl with the head of John the Baptist . Further scenes depict the miracles of Christ, the resurrection of Christ, the birth of Mary and her dormition. All depictions are distinguished by their lively expression and harmonious coloring.

Building archeology

A three-aisled early Christian basilica stood on the site of the church before it was built. There are indications that it was founded as a monastery church, which Friedrich Hiller von Gaertringen pursued as early as 1900. However, due to many renovations, the monastery cannot be verified architecturally. Some walls and elements from the previous building have been used in the church, including the four strong pillars that support the central dome and parts of the east wall, left and right of the apse. Today's partition between the nave and the narthex was probably the original west wall of the basilica. The passage to the ship with marble door posts was the entrance gate. The larger entrance door on the north side was probably reused as a spoiler . Spolia from the ancient city of Alt-Thera on Mesa Vouno , a foothill of Profitis Ilias , was used at various points in the construction . These include Doric columns with capitals and bases , several architraves, round altars and carved bull heads.

|

|

|

|

| Access to the church from the main entrance on the west |

View of the frescoed south wing |

Icon stand of Panagia Glykofilousa |

Chancel with window in the eastern apse |

use

Since 1931 is the Panagia Episkopi the central sanctuary of the island of Santorini, since 1962 it is under monument protection . Every year on August 15, which is a feast day in all of Greece, the central celebration of the ' Dormition of Our Most Holy Master, the Theotokos ' takes place in and on the former bishop 's church. This feast corresponds in the Orthodox Church to the Assumption of Mary as it is celebrated in the Catholic Church. The icons of the church are carried around the church in a procession. In memory of the former goods of the church, a bowl of puree made from flat peas and beans is given to all believers after the service.

history

A local legend reports that in a chapel driven into the slope next to today's church hung an icon of Panagia , which left its place several times for no apparent reason and was found again on a nearby volcanic hill. The believers saw this as a sign that the icon no longer wanted to hang in the underground chapel, but in a free-standing church.

Another legend, recorded in 1701, tells that the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I (1048–1118) had given the church the entire land outside the former villages of Gonia and Pyrgos up to the summit of the highest mountain on the island. His wife Irene would have donated a generous amount of money. A certificate in the form of a Chrysobullos logo was drawn up about the foundations , the golden seal would have carried the image of the church. Such a certificate and a corresponding seal could not be found.

A proven reference to Emperor Alexius is the now largely destroyed inscription Ἀλέξιος ἐν Χῶ τῶ Θῶ αὐτοκράτωρ Ρωμαίων ὁ Κομνινὸς καì πιστὸς βασιλεύς (Alexius, in God Christ ruler of Rhomäer , Komnenos and pious Emperor ') inside the main entrance. There is also a fresco with a portrait of the emperor, which is dated to the 16th century and is therefore not contemporary, and it is badly damaged. In the literature it is discussed whether it could possibly also be Alexios II , who ruled from 1180 to 1183. Instead, the motifs in the marble inlays are cited, in particular the depiction of birds and the frequency of the crosses would correspond to illustrated manuscripts from the time of Alexios II. Against this is the fact that Alexios I has verifiably run a church building program and also has churches on neighboring islands Time to be dated. A foundation of the church before the death of the emperor in 1118 is therefore not excluded; various local texts, which give exact dates, come from the 19th century and probably have no factual basis.

The recorded history of the church begins in 1207 when the island of Santorini became part of the Duchy of the Archipelagos , ruled by the Republic of Venice , as a result of the fourth crusade . The Venetians drove the island's Orthodox bishop out and installed a Latin bishop. The Panagia Episkopi church was named as the seat of the displaced Orthodox bishop. While his Latin successor took his seat in Skaros on the edge of the crater, a Latin altar was erected next to the Orthodox one in Panagia Episkopi .

When the island, along with the whole of the Aegean , was conquered for the Ottoman Empire by Khair ad-Din Barbarossa in 1537 , the Orthodox bishop returned and took the church again as his bishopric. The island's Catholics did not accept this, largely because of the Church's valuable property and the agricultural and other income from it. The dispute escalated, both parties took up arms, so that in 1612 the conflict was sustained in front of both Patriarch Neophytos II and Sultan Ahmed I. Under their pressure, the two parties were able to come to an agreement in 1614, the church lands were divided and both denominations were allowed to hold their services in the church.

The dispute between Orthodox and Catholics flared up again as a result. It was about who was allowed to hold the first evening service on the central feast day of the Dormition of the Virgin , on which a large procession to the church took place, and who was to celebrate the great mass on the day itself. The conflict simmered until 1758, when Patriarch Kyrillos V issued a decree that all Orthodox who shared a church with Catholic Christians would be excommunicated . Sultan Mustafa III. issued a Ferman , according to which the Church was transferred to the Orthodox Christians. The Catholics ignored the instruction because they knew they were under the protection of the Western ambassadors in Constantinople and continued to hold masses in the church. In 1767, the Patriarch and Sultan issued another order asking the Catholics to build an annex to the church, which was intended for their services. In the same year, a small room with a simple barrel vault was created in the southeast of the church . It is accessible through a door in the south wall and has a breakthrough to the chancel, in which both altars are located.

Apart from the division of the land between the denominations in 1614, in 1711 the upper part of the church land with the summit of the Profitis Ilias mountain and two small chapels on the mountain was separated. It was transferred to two brothers on the island who founded the monastery of the Prophet Elias , which still exists today . In 1827 the new church in Fira , the main town on the island, was consecrated. The bishopric moved there. After the establishment of the Kingdom of Greece in 1832, the church's property was gradually expropriated. From 1850 the church sold its remaining property, the last vineyards in 1902.

In 1915, a fire in the Panagia Episkopi building destroyed most of the books, church documents and priestly robes. The icons of the church remained undamaged. The earthquake of July 9, 1956, in which large parts of Mesa Gonias were destroyed, caused severe damage to the church building. The inhabitants of Mesa Gonias subsequently founded the coastal town of Kamari below the traditional place. The reconstruction and a thorough restoration of the Panagia Episkopi lasted until 1986. During the work, all 26 portable icons were stolen in 1982, including three frescoes removed from the walls and framed. They never showed up again.

literature

- Anastasios Orlandos : Ή 'Πισκοπή τής Σαντορήνης (Παναγία τής Γωνιάς). In: Archeion tōn Byzantinōn mnēmeiōn tēs Hellados 7, 1951, pp. 178-214.

- Matthaeos E. Mendrinos: Panagia Episcope - The Byzantine Church of Santorini , published by the Bishops' Conference, 2nd edition 2000 (translation from Greek into English by Vassiliki Alipheri)

- Claudia Barsanti, Silvia Pedone: Una nota sulla scultura ad incrostazione e il templon della Panaghia Episcopi di Santorini. In: Mélanges Jean-Pierre Sodini. Paris 2005, ISBN 2-9519198-7-5 , pp. 405-425.

Web links

- Angeliki Mitsani: Ναός Επισκοπής Θήρας. Περιγραφή. Ministry of Culture and Sport (Greece), accessed October 24, 2013 (Greek). (Short version also in English)

- Episkopi (Mesa) Gonia. Panagia Episkopi. www.santorini.gr, accessed on October 25, 2013 (English).

- Santorini Churches: Panagia Episkopi Church. www.santonet.gr, October 18, 2007, accessed October 24, 2013 (English).

- Svetlana Tomekovic Database of Byzantine Art: Panagia Episkopi , Princeton University - Index of Christian Art

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Angeliki Mitsani: Ναός Επισκοπής Θήρας. Περιγραφή. Ministry of Culture and Sport (Greece), accessed October 24, 2013 (Greek).

- ↑ a b Barsanti, Pedone 2005, p. 419.

- ↑ Mendrinos 2000, pp. 17-21.

- ↑ Barsanti, Pedone 2005, p. 424.

- ↑ a b Mendrinos 2000, pp. 36-37.

- ↑ Mendrinos 2000, p. 37.

- ↑ Barsanti, Pedone 2005, p. 425.

- ^ Episkopi (Mesa) Gonia. Panagia Episkopi. www.santorini.gr, accessed on October 25, 2013 (English).

- ↑ Mendrinos 2000, pp. 23-26.

- ↑ Mendrinos 2000, p. 15.

- ↑ Mendrinos 2000, pp. 10-11 .; Ministerial Ordinance No. 9763. (PDF) In: Government newspaper of the Hellenic Republic, Volume 2, Sheet No. 415. November 19, 1962, accessed on February 7, 2014 .

- ↑ a b c Mendrinos 2000, p. 6.

- ↑ a b Recorded by Antonio Giustiniani, the bishop of Syros in 1701, printed in: Georg Hofmann : Vescovadi cattolici della Grecia V. Thera (Santorino) (= Orientalia Cristiana Analecta 130). Pontificium Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, Rome 1941, pp. 80-106, here p. 94f.

- ↑ Mendrinos 2000, p. 26.

- ↑ Christopher Walter: A New Look at the Byzantine Sanctuary Barrier . In: Revue des études byzantines 51, 1993, pp. 203-228, here p. 209.

- ↑ Barsanti, Pedone 2005, pp. 415f.

- ↑ Mendrinos 2000, p. 7.

- ↑ Mendrinos 2000, pp. 7-10.

- ^ Giorgos Ioannis Alexakis: Santorin, Thirasia . An island of lava. Michalis Toubis, Koropi 1998, ISBN 978-960-540-259-4 , pp. 102 .

- ↑ Mendrinos 2000, p. 10.

- ↑ Mendrinos 2000, p. 41.

- ↑ Emile A. Okal, Costas E. Synolakis, Burak Uslu, Nikos Kalligeris, Evangelos Voukouvalas: The 1956 earthquake and tsunami in Amorgos, Greece . In: Geophysical Journal International . tape 178 . Wiley, 2009, p. 1535 ( online [PDF; accessed February 3, 2014]).

- ^ A b Santorini Churches: Panagia Episkopi Church. www.santonet.gr, October 18, 2007, accessed October 24, 2013 (English).