Picts

Picts ( Latin: picti Latinized form of the old Greek πύκτις "the painted ones") is the Roman name for peoples in Scotland . The name is traced back to the custom of the Picts to get a tattoo . The Pict stones are out of the question as a designation of origin , as they were made between the 5th and 9th centuries. The peoples referred to by the Romans as Picts are probably not one people ( ethnic group ), but rather different peoples with differing cultural traditions, who, however, entered into political and military alliances in the face of common enemies (Romans, Scots , later also Vikings ) .

The origin of the Picts is unclear. Their language and culture disappeared when the Picts and Celtic Scots kingdoms were united under Kenneth MacAlpin in 843 AD .

Little is known of the culture of the Picts. Almost only late picture stones and steles have survived that are richly decorated with characters, some in their own language, and ornaments . Among these are the cross slabs of the 9th century. Place names and the patterns on their late handicrafts and engraved stones suggest that the Pictish peoples may have been British Celts . Their enemies, however, the Scots, were Gaelic - Irish Celts.

The Picts in History

The only contemporary written documents about the Picts come from the Romans , which mainly describe the relationship between Romans and Picts. The Poppleton manuscript , on which the Pictish Chronicle is based, is significant for the history of the Picts . The Picts are first mentioned by Eumenius in AD 297 .

Encounters between Romans and Picts

The first documented incidents with the Picts occurred in the 1st century when the Romans conquered the British Isles as far as the Forth and the Clyde . Since the year 122, when he visited Britain , the Roman Emperor Hadrian had Hadrian's Wall built, a wall with integrated forts for the troops stationed there, against the constant attacks by "Caledonians and other Picts" . 142 began his successor Antoninus Pius at the height of Forth and Clyde with the construction of the advanced Antoninuswall , which was shorter but probably not finished. The Romans only maintained the wall until the year 161 and then retreated back to Hadrian's Wall.

In 184 the northern peoples overran Hadrian's Wall and caused considerable damage to the Romans, but the governor Ulpius Marcellus was able to restore it to its former state, and his successor, the later emperor Publius Helvius Pertinax , ensured a longer period of rest between 185 and 187; thereupon emperor Commodus took on the victorious name Britannicus . In 208 the then Roman governor of Britain called on the emperor Septimius Severus to help. This fought back the insurgents in hard battles until 210 and was therefore given the same winner's name. After his death in February 211, his sons Caracalla and Geta left the British north to fend for themselves and returned to Rome. During the rest of the 3rd century Hadrian's Wall formed the border of Britain, but around the year 300 fighting on the northern border is documented again.

The Pict Wars

Since the summer of 305 the Roman emperor Constantius I , later nicknamed Chlorus , undertook a successful campaign against the "Caledonians and other Picts". For this he took on the winning name Britannicus Maximus for the second time in the same year , but died on July 25, 306 in Eboracum , today's York . His grandson Constans waged a war against the Picts in 343, which is symbolized in a series of coins by the depiction of the emperor in a ship. In 360 the Emperor Julian dispatched his master Lupicinus against the Picts and the allied Scots of Ireland who had invaded Britain.

After that there were more and more skirmishes with the northern peoples. For the year 364, the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus names the Dicalydones, Verturiones, Skoten, Attacotti and Saxons as the peoples who caused problems for the Roman Empire in Britain. To this day it is unclear what relationships these peoples had with one another and where the others settled apart from the Scots and Saxons.

In 367 the Picts, Skots and Attacotti allied themselves in a Conspiratio barbarica ('barbaric conspiracy'). The Roman general Flavius Theodosius was sent to Britain by Emperor Valentinian I to put it down; after that, Hadrian's Wall was renovated in 368. The subsequent peace only lasted until 382, when the Picts and Scots invaded Britain again, but they were repulsed by the then military commander Magnus Maximus .

At the beginning of their clashes in the 1st and 2nd centuries, the Picts were reluctant to accept the expansion of Roman rule in Britain. They used the slow decline of Roman authority in the 3rd century for raids because usurpations and the associated troop withdrawals on the continent promised easy prey in the less intensely defended country. Treasure finds with silver handicraft items suggest that the Picts melted these and Roman coins. A more speculative theory about the raids is that increased population pressure forced the Picts to spread south.

Two non-Roman sources attest to the activities of the Picts:

- A received letter from St. Patrick to Coroticus (a south-west Scottish king) from the 5th century reprimands him for his "shameful, vile and unchristian" behavior.

- The monk Gildas (500-570) lists three Pict Wars in 540: the first of 382, which was crushed by Magnus Maximus, the second of 396-398, led by the army master Stilicho and the third in 450, in which the Picts were beaten by Flavius Aëtius . The latter event is fictional, however, because Roman rule in Britain gradually waned after 410, when Emperor Flavius Honorius withdrew the remaining regular troops to protect Italy. However, Gildas mentions a final request for help from the Roman Britons to Aëtius for 446, which went unheard: At that time, however, the Saxons and Angles had already started to cross over to Britain and take possession of it.

Pict land after the withdrawal of the Romans

After the Romans left, the sources became very imprecise. The king list obtained from the monk Gildas cannot be reconciled with other sources, and modern historians suspect that the atrocities described therein were greatly exaggerated, if not fictitious, by Gildas.

After the Romans left the province of Britannia, the Picts advanced south. In 550 Bridei mac Maelcon was crowned "King of the Picts", who is said to have played an important role in the unproven conversion of the Picts to Christianity during the 6th century. Bridei was a dynamic leader. He united northern and southern Picts and managed to defeat the Skots.

After Bridei's death in 584, the Anglo-Saxons began to put pressure on the Picts under Æthelfrith , King of Northumbria . After he beat the Skots, Picts and Anglo-Saxons had become neighbors. At first, relations between the two peoples seemed to be positive and peaceful. There were even marriages among the respective royal families. In 668, however, Oswiu , king of Northumbria, seems to have expanded his territory to "Piktland".

For over 30 years, South Pictland was ruled from Northumbria. Wilfrid reports of a Pictish revolt from this time, which was cruelly suppressed by Ecgfrith of Northumbria: He is said to have built a bridge of Pictish bodies over two rivers, so that his army could cross these dry feet around the remaining Pictish army knock down. In 685, however, the Pict king Bridei mac Bili Ecgfrith defeated in the Battle of Dunnichen Mere . The Northumbrians remaining in Piktland were enslaved.

In 706 Nechton mac Derelei became leader of the Picts. He ended the conflict with Northumbria and began diplomatic relations with the Anglo-Saxons. However, Nechton had to assert himself again and again against attacks from his own ranks during his reign. His brother Ciniod was murdered by the King of Atholl.

In 724 Nechton abdicated and went to the monastery. His successor was fiercely contested, and in 729 Oengus mac Fergus finally took power. Oengus remained on the throne until his death in 761. During this time he waged war against the Scots, the Irish and Northumbria.

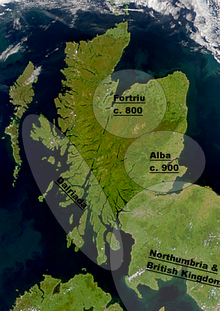

After the death of Oengus, the history of the Picts becomes unclear again. There appears to have been a lot of skirmishes, but also some common kings of Scots and Picts. In the middle of the 9th century, Kenneth MacAlpin , King of the Scots, allied with the Vikings and defeated the Picts. In 843 he was proclaimed King of the Scots and Picts. The Picts were incorporated into the Scottish Empire and the two cultures seem to have merged into one another.

language

The origin and the classification of the Pictish language could not be sufficiently clarified until today. With three popular theories each attempt is made to use the pictic as

- celtic ,

- non-Celtic but Indo-European

- non-Indo-European language

classify. None of the models has gained general recognition to date.

Inscriptions on engraved stones prove that the Picts spoke their own language with Irish-Gaelic , but also British loanwords . The number and type of non-Gaelic elements make a non-Celtic, possibly even non-Indo-European origin conceivable.

A spindle whorl , the so-called Buckquoy spindle whorl , has an Ogham inscription which, prior to the research results of Katherine Forsyth (published from 1995), was considered to be written in Pictish. Research now (especially in the wake of Katherine Forsyth's publications) tends to view the Picts as Celtic-speaking. Possibly they were simply that part of the British Celts that was never subjugated by the Romans and that was cut off from the rest of Britain by the construction of the Roman border walls. Pre-Indo-European substrate is assumed to be in the names of some islands, which have no known etymological explanation and do not seem to come from a Celtic or Germanic language.

religion

Little more is known about the religion of the Picts than what Roman historians and Christian monks have written.

cult

Almost certainly there were a large number of deities among the Picts, including local deities of mountains, trees, rivers, lochs, animals, or forests. For example, the large number of bulls engraved stones found in the vicinity of Burghead could suggest a bull cult.

Whether the Picts knew about human sacrifice is controversial. Pictish stones from the later, Christian period depict trees decorated with human heads. Other engravings show people in kettles, which could be representations of sacrifices or rebirth - some prominent Celtic legends revolve around the kettle (Kettle by Gundestrup) the rebirth.

Caves ( Sculptor's Cave , Wemyss Caves ) or prehistoric stone circles and formations may have served as cult centers .

Burials

There are a number of Pictish graves in Scotland. It was previously believed to be concentrated in the east and northeast of Scotland, but aerial photographs and recent excavations show typical Pictish burial mounds in the Borders in Lothian and Dumfries and Galloway . The Picts seem to have buried their dead in a wide variety of ways: burials and cremations, burials in stone boxes , under cairns and round mounds of earth (barrows). There is also excarnation . It is unclear how these practices were chosen for any particular person or group.

Cairns predominate in the north of Scotland. Cairns often contain a number of individual burials, sometimes five to six, while burial mounds almost always contain only one grave. A burial ground may contain cairns and barrows, and excavations and dating indicate that these were contemporary, usually dating from the 3rd to 6th centuries AD. Thereafter, burials in unprotected grave fields become less common; more recent burials arise more often in connection with churches. Garbeg at Drumnadrochit with results from the 10th to the end of the 11th century is rather an exception.

The graves are always oriented roughly east-west, even in the centuries before the introduction of Christianity. In the unusual, rather rare, burials, the head is in the west. Remarkably, almost all Pict burials are free of gifts, in contrast to the richly furnished Anglo-Saxon burials in England at the time.

The Pictish Church

The Picts were reportedly Christianized by St. Ninian and St. Columba during the 5th and 6th centuries . Modern historians suspect, however, that Christianity in Piktland could only finally establish itself in the course of the 8th century or even later. Most of the evidence of an early Pictish church is stone sculptures and engravings (e.g. Pictish crosses ).

Corporate structure

The Picts were tribal (i.e., organized into tribes), rural (rural), hierarchical, and family-centered.

Piktland was thought to be divided into seven independent regions (kingdoms): Fortriu (now Strathearn and Menthieth), Fothriff (now Fife and Kinross), Circhenn ( Angus and Mearns), Fotla (now Atholl), Catt, Ce and Fidach. These regions were inhabited by tuaithe (sing. Tuath ) or derbfhines (family associations). A derbfhine consisted of the descendants of a common great-grandfather (i.e. all 2nd degree relatives in the paternal line). The land belonged to the family association and was farmed together.

The women had a high status - higher than that of the Romans and other contemporary cultures, for example. There is evidence from Roman authors that there were female warriors among the Picts.

The society was structured strictly hierarchically ( professional society ). Hereditary or elected kings were at the top, slaves and serfs at the bottom.

Kings

The royal dignity was hereditary. However, various sources contradict one another as to whether it was inherited through the father or mother line. The names of the kings ( maqq or mac , 'son of ...') and other evidence rather point to the father line, although it cannot be ruled out that the mother line was used in exceptional cases.

Noble

Below the kings there were different degrees of nobles. Nobles were on the one hand warriors, but also professionals such as poets, artists, craftsmen, legal scholars, historians and musicians. Their abilities allowed them to assume a higher status than they were due to be born.

Free

The majority of the population belonged to the free. Free farmers were and paid taxes from the harvest to the king, who in return provided them with military protection.

Serfs

At the bottom of the hierarchy were slaves and serfs. They are mentioned in the 5th century in St. Patrick's letter to King Coroticus : Patrick scolds Coroticus for buying Christian slaves.

Art of war

Many Pictish stone steles and sculptures depict warriors, so that historians can get a fairly precise picture of a Pictish army. On the sculptural stones of Aberlemno the way of fighting of the Picts of the late migration period and the early Middle Ages can be clearly seen. The battle at Dunnichen Mere from 685, in which Ecgfrith of Northumbria was defeated by Bridei Mac Bili, is probably shown.

In the center of the Pictish army is a typical shield wall , symbolized by three warriors standing one behind the other. The one in front fights with a sword and a round shield, while the next warrior has a shield around his neck and fights with a long spear from the second row. The third warrior stands ready to fill any gaps that may arise. On the flanks is the cavalry armed with swords, spears, and shields. Some historians also see a kind of comic strip in the illustration, which shows the course of the battle. Accordingly, the cavalry would not be on the flanks of the foot troops.

weapons

The most important weapons of the Picts appear to have been the spear and the sword . Spears are depicted with leaf-shaped tips. There were both javelins and spears for hand-to-hand combat. The swords were made of iron and had a crossguard and pommel. These were probably richly decorated depending on the status of the owner. In only two cases of the sword scabbards have the chords (lower end of the scabbard) made of silver. They come from the St. Ninians Horde from the Shetlands, are U-shaped and richly decorated. Such chords can also be seen on the picture stones, so that one can assume that this is a typical shape.

In addition to spears and swords, axes appear to have been used in hand-to-hand combat. Depictions show both one-handed and two-handed war axes.

There are also depictions with bows and possibly crossbows. The Picts would then have used the crossbow relatively early in comparison with other peoples.

armor

So far, archaeologists have only found smaller fragments of chain mail. Silver hooks very likely come from Roman Loricae squamatae .

Referring to the Caledons and Maeatae (peoples of what is now Scotland), Herodian writes that the British have no armor.

There were apparently two different types of shield: On the one hand, rectangular or oblong-oval shields, which were similar to the Roman scutum , but were smaller and more manageable; on the other hand the Gaelic round shields already described, which enjoyed great popularity. They were depicted on many stones, but also in the Book of Kells and were possibly of Irish origin.

Armor cannot be identified with certainty on any picture stone. The central figure of the Sueno's Stone (obviously a leader) could be wearing a gambeson or something similar. Whether helmets can be seen on the Dupplin Cross is controversial.

transport

According to the records of Tacitus , the Caledonians used war chariots in the battle of Mons Graupius . Although war chariots appear on Irish stone sculptures, no such depictions have been found in northern Scotland. While the Gauls had given up the chariots when Caesar arrived, they were probably used by the British until the 1st century AD. Until the appearance of the picture stones (around 400 at the earliest) they were also given up here.

The horse, however, was an important means of transport for the Pictish warriors. It was ridden with or without a saddle. In addition, boats were used for troop transport and war.

economy

The Pict economy was largely based on agriculture. However, they also conducted brisk trade with other countries and cultures of the time. They obtained precious metals and foreign currency through raids on the Romans and their neighbors, the Skots.

Agriculture

The agriculture of the Picts was based on animal husbandry . 61% of the bones found by researchers from that time come from cattle, 31% from pigs and only 8% from sheep and goats.

The herds of cattle were small and only as many animals were slaughtered as necessary. Sheep and goats were raised for their meat, not for their wool.

Craft

Many handicraft items were made from organic materials and did not survive time. Numerous everyday objects are depicted on engraved stones: carved benches and chairs, day beds, beautifully decorated tripods for the equally beautifully decorated kettles with handles.

The Picts also knew a variety of tools: pliers, anvils, hammers and axes for various purposes are depicted on various stones.

Weaving does not seem to have been widespread in Piktland. There are no finds of looms or tools required for them after the year 200.

Woodworking, on the other hand, was widespread. There are some very beautiful wooden containers with carved ornaments from the Loch Glashan area (Argyll), in which tools were kept. Spatulas, clips, needles, handles, spindles, combs, etc. were made of wood, but also of bone and were richly decorated.

Few leatherworks survived. A shoe was found in Dundurn that was made from one piece and decorated over and over. This indicates a high level leather craft.

Quite a lot of works made from bones have been preserved. These are sewing tools, needles, clothes needles, combs, belt buckles, etc. Many of these objects are not only decorated with carvings, but also with bronze rivets.

Stone was used by the Picts to make grindstones, molds for metal bars, and pot lids.

The Picts themselves did not make glass. However, it appears they melted imported glass to make glass beads and bracelets.

The most widespread craft was blacksmithing. Iron was made into a variety of objects: fasteners, buckles, arrow and spearheads, axes, chisels, awls, hammer heads, knives, nails, metal hoops for barrels, handles, swords.

Not only iron, but also bronze and silver were melted and worked by Pictish craftsmen. Molds have been found to show that these metals were cast. The molds consisted of two parts, and the complex three-dimensional decorations were already carved into the mold. At Dunadd in Dalriada , objects of tin were also made in this way; and in Dunadd and Dunollie also some of gold.

trade

Pottery and containers found indicate that the Picts traded with other peoples. Apparently the merchant ships came from the Mediterranean along the Atlantic coast across the Irish Sea to Scotland.

The neighbors in Northumbria and Ireland were also busy trading. Pictish metalwork has even been found among the Vikings.

clothing

A single piece of clothing has stood the test of time. It is the so-called Orkney Hood , a cowl that was found while cutting peat in 1867. It is made of (presumably natural brown) wool in a herringbone weave, on which ribbon-woven ribbons and fringes are attached. Further conclusions about traditional costume elements can be drawn from the records of the Romans as well as from the stone sculptures.

Women wore a long shirt and a wrap that was held together with a fibula . The women depicted on the sculptures wore their hair relatively short - no longer than shoulder-length and tied up.

In the pictures, men wear a kind of tunic and the same cloak tied together with a fibula as the women , unless they were wearing the war equipment described above . Pictish men wore their hair long (sometimes back-length) and had beards.

Both men and women wore brooches, clothes pins, hairpins, finger rings , bracelets and chokers as jewelry .

pastime

The Picts knew various board games , some of which originally came from the Irish and the Romans.

There is also evidence that making music and singing were popular pastimes. Two different types of harps were found: large instruments that stood on the floor and were played seated (similar to today's concert harps). There was also a smaller harp that the musician held in his hand to play.

The horn was also played (Sachsenhorn?). On the stone of Nigg there are figures with a cymbalum , an instrument that has not been found anywhere in the Pictish region.

literature

- Jürgen Diethe: The Picts: History and Myth of an Enigmatic People . König, Greiz 2011, ISBN 978-3-939856-44-3 .

- Lloyd and Jenny Laing: The Picts and the Scots. Alan Sutton, Stroud 1993, ISBN 0-86299-885-9 .

- Nick Aitchinson: The Picts and the Scots at War. Alan Sutton, Stroud 2003, ISBN 0-7509-2556-6 .

- William A. Cummins: The Age of the Picts. Alan Sutton, Stroud 1995, ISBN 0-7509-0924-2 .

- George and Isabel Henderson: The Art of the Picts. Sculpture and Metalwork in early medieval Scotland. Thames and Hudson, London 2004, ISBN 0-500-23807-3 .

- Alexander Demandt : The late antiquity. Roman history from Diocletian to Justinian 284-565 AD. 2nd edition, Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-07992-4 .

- Benjamin Hudson: The Picts. Wiley-Blackwell, 2014. ISBN 978-1-4051-8678-0 (linen); ISBN 978-1-118-60202-7 (paperback).

- Katherine Forsyth : The ogham-inscribed spindle-whorl from Buckquoy: evidence for the Irish language in pre-Viking Orkney? In: Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland . tape 125 , 1995, pp. 677-96 ( online [accessed July 12, 2012]).

Movies

- Centurion - Fight or Die ; UK 2010; Director, Screenplay: Neil Marshall; Synopsis: Battle of the Ninth Roman Legion against the Picts in AD 117; FSK: 18

- The eagle of the ninth legion ; USA, UK 2011; Director: Kevin Macdonald; Script: Jeremy Brock; Synopsis: the lost standard of the Ninth Legion is sought beyond Hadrian's Wall in the land of the Picts; FSK 12