Religion of the Bavarians

The beliefs widespread among the Bavarians in the transition phase from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages are referred to as the religion of the Bavarians .

Written sources

The vita of St. Severin von Noricum from the 5th century gives extensive information about the regions of today's Lower and Upper Bavaria, the Salzburg region and western Upper Austria, which were later settled by the Bavarians .

Severin von Noricum, a Christian Roman, did missionary work in Noricum at a later date and took on important organizational tasks, as the administration was left to decay. After his death in Favianis, today's Mautern in Lower Austria, Eugippius wrote a comprehensive work on the work of Saint Severin, which provides a comprehensive insight into the situation in the province of Noricum at that time. The Vita Sancti Severini reports that the Romanized Norics in the 5th century were all Christians, as were the Germanic tribes living under the Romans.

About the Teutons on the other side of the Danube, who would later become the main part of the Bavarian population, one only learns more details from the Rugians . After St. Severin, however, the written tradition breaks off completely and there is only information about this region from the middle of the 6th century, which is very sporadic and comes from travelers like St. Venantius Fortunatus . It was not until the mission of Scottish monks in the early 8th century that the creation of texts flourished again in the Bavarian region. These texts from the 8th century were all written by Christian monks and contain practically no information about the beliefs of the Bavarians from the time before. As a result, there are very few written sources about this time gap of 200 years, especially not about the religion of the Bavarians, but rather about political events.

Archaeological sources

Grave goods are an essential source of practiced religiosity. On the basis of grave finds and their additions it can be established that the ancestors of the Bavarian people had ideas of whatever kind of life after death. Most of the finds date from the 6th to 7th centuries.

There were weapons rank insignia for men and women’s jewelry as status symbols . In addition, objects of everyday use such as jugs and tools were available. Gold leaf crosses should also be mentioned, which varied in shape as jewelry additions . Charon coins have also been found as symbols of faith given along with them. The archaeologist Roland Knöchlein recognizes the end of any previously practiced Germanic religiosity at the latest at the row cemetery of Waging .

Isolated additions can still be found in the 9th - 11th centuries. However, they were replaced with the replacement of the row field graves by the cemeteries in the newly built or already existing church buildings.

Important finds, on which the archaeological knowledge of the beliefs of the Bavarians are based, were found in the following places:

- Waging am See , Traunstein district

- Petting at Waginger See

- Heining near Laufen on the Salzach

- Emmering , Fürstenfeldbruck district

- Staubing near Kelheim in the Altmühltal

- Kemathen near Kipfenberg in the Altmühltal

- Altenerding

- Moosinning near Erding

- Steinhöring , Ebersberg district

- Ergolding , Landshut district

- Alburg near Straubing

- Niedertraubling , Regensburg district

- Pocking slip near Passau

- Wels in Upper Austria (excavations at the train station)

- Rudelsdorf near Hörsching , Linz-Land district

- Linz-Zizlau

- Schwanenstadt (Pausinger Villa), Vöcklabruck district

Religious Traditions

The Romanesque population in the former Noricum Ripense and Raetia Secunda had been largely Christian since the 4th century . The written records from old Bavarian sources and Latin manuscripts from this region report very little of a pre-Christian religion of the Bavarians. The only source of information is therefore archeology .

The transition from antiquity to the Middle Ages is an era in which the Bavarian tribe began to form. Even then there was a juxtaposition of beliefs that had come to the country in the wake of the Romans, such as Judaism and Arianism . From the Goths , the Arian variant of Christianity quickly spread to neighboring tribes and to the groups from which the Bavarians had emerged in the 6th century.

However, the question of how widespread this form of Christianity was among the Bavarians is disputed. Archaeological findings do not give a clear answer to this question. For example, some researchers interpret the existence of grave goods as a pagan custom, indicating the existence of a Germanic religion, while others attribute the turning away from the cremation of the dead to burial to a Christian influence. The missionary work of the Goths through the Wulfilabibel coincides with their task of cremation. It is also conceivable that a syncretic concept of faith could emerge from Germanic and Greek-Christian elements. This is supported by the addition of clearly Christian objects in the Bavarian burial grounds, such as the custom of putting gold leaf crosses in the grave of the dead from the 7th century from Lombard Italy .

Especially in the larger former Roman cities and forts, such as Iuvavum (Salzburg), Lauriacum (Enns), Boiotro (Passau), Castra Regina (Regensburg), Augusta Vindelicorum (Augsburg) and in the Tyrolean and Salzburg alpine valleys existed despite the turmoil Migration of peoples partly still a Romanesque population. These novels, which remained in the Bavarian settlement area, were all Catholic Christians, as can be seen from the Vita Sancti Severini . They continued to venerate local Christian saints such as Florian von Lorch and Afra von Augsburg and often lived next to the newly immigrated Germanic tribes.

Pieces of jewelery from graves, which were dug around 500, already suggest a Christian population for this time. She clearly professed her Christianity. Archaeologists deciphered the “Unterhaching Code”, the Christian imagery of the early Middle Ages, from finds from excavations in Unterhaching .

Romanesque graves can be found next to possibly Germanic graves in Bavarian row grave fields. The proselytizing by Irish-Scottish monks beginning in 615 then led to a larger extent to the conversion of the Bavarians to the Catholic variant of Christianity. Saints Eustasius , Agilus and Emmeram of Regensburg were of particular importance. But it was only through political pressure from the more powerful Franks that Catholicism was able to gain a stronger foothold among the Germanic Bavarians, with Saints Korbinian and Rupert playing an important role. For example, around 700 Catholic dioceses were established in the Bavarian Duchy, the oldest of which was Salzburg (696), later Regensburg (around 700), Freising (716), Passau (739) and Eichstätt (mid / 2nd half of the 8th century). . The final followers of Arianism were probably only persuaded to convert after the victory of the Franks over the Lombards, which were closely associated with the Bavarians, in 774. The overthrow of the likewise Arian Lombards by the already Catholic Franks meant the final end of Arianism in Europe.

A Christian synodal activity since the foundation of the diocese in 739 goes hand in hand with Bavarian regional synods under Duke Tassilo in Dingolfing around 770 AD and Neuching in 772. Bishop Arn von Salzburg invites you to a council held in 799 in Reisbach , an important Bavarian town in the early Middle Ages. This was the first time and place handed down to the Bavarian Metropolitan Synod of Bishops. Bishops, abbots, priests, archpriests and deacons from all over Bavaria were out and about on early medieval streets to meet in Reisbach.

Catholic Christianity has slowly established itself among the Bavarians, through cultural exchange with the Romans since the final phase of the Western Roman Empire until the final integration of Bavaria into the Frankish Empire in 788. To what extent Germanic rites or also Celtic and pagan-Roman relics in the Romanesque Population of the Alpine region was actually passed on is not documented. The Germanophile folklore of the 19th and early 20th centuries asserted a continuity from pre-Christian times to today's customs, a point of view that is now heavily criticized and questioned. Recently, interest in the Alpine Celts has risen sharply and so a hidden continuity Celtic rites is occasionally later bajuwarisierte keltoromanische rest of the population to present-day customs asserts a thesis which stands on a weak scientific basis. In addition, a Slavic origin of some customs is assumed for the eastern regions in Lower Austria, Styria and Carinthia, which were later populated by the Bavarians. However, none of these theories have been substantiated.

State of research

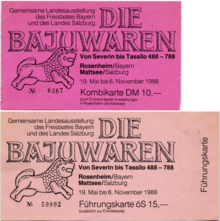

In 1987/88 the extensive row grave field in Waging am See was found and archaeologically developed. On this occasion, Rosenheim and the Salzburg municipality of Mattsee jointly organized a Bavarian jewelery exhibition in 1988 under the title The Bavarians - From Severin to Tassilo 488 to 788 . Since then, new archaeological accidental finds from the period of the 6th and 7th centuries have been made through building projects, which further increased the level of knowledge. It was not until 1990 that one of the oldest graves identified as Bavarian was discovered in Kemathen near Kipfenberg , and in 1991 another early medieval burial ground was found in Petting am Waginger See. The campaign at the grave field in Schwanenstadt in Upper Austria was completed in 1996 and the grave field in Wels was not noticed until 2005 through renovations at the local train station. This last find offers particularly interesting findings as there is a continuous burial there from the 4th to the 8th century.

literature

- Marion Bertram: The early medieval grave fields of Pocking-Inzing and Bad Reichenhall-Kirchberg - Reconstruction of two old excavations; Museum for Pre- and Early History, Berlin, 2002, 399 pages, ISBN 3-88609-201-1

- Thomas Fischer : The Bavarian row grave field of Staubing - Studies on the early history in the Bavarian Danube region . Lassleben, Kallmünz 1993, ISBN 3-7847-5126-1 .

- Ronald Knöchlein: The row grave field of Waging am See , series of publications by the Bajuwarenmuseum No. 1, Liliom Verlag, Waging am See, 2000, ISBN 3-927966-75-4

- Hans Losert, Andrej Pleterski: Altenerding in Upper Bavaria - structure of the early medieval burial ground and "ethnogenesis" of the Bavarians ; srîpvaz-Verl., Berlin (inter alia), 2003, 499 pages, ISBN 3-931278-07-7

- Ludwig Pauli: Pagan and Christian Customs In: Hermann Dannheimer: The Bajuwaren - From Severin to Tassilo 488 to 788 - . Free State of Bavaria, Munich 1988, pp. 274–280.

- Knut Schäferdiek, Winrich Alfried Löhr, Hanns Christof Brennecke: Schwellenzeit: Contributions to the history of Christianity in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages ; Chapter: Was there a Gothic-Arian mission in southern Germany? (Page 203ff), Walter de Gruyter Verlag, 1996, 546 pages, ISBN 3110149680 , in full text on Google Books

- Rudolf Simek : Religion and Mythology of the Teutons , Darmstadt, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Theiss Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-8062-1821-8

- Tovornik Vlasta: The Bavarian burial ground of Schwanenstadt, Upper Austria . Monographs on early history and medieval archeology. Volume 9, 2002. 152 pages, ISBN 3-7030-0372-3

Web links

- Dieter Dörfler: The Bavarians from Waginger See. A visit to the Bavarian Museum recalls the life of our ancestors .

- Karl Heinz Rieder: Kemathen - The first real Bajuware. Germanic warrior grave in the Altmühltal reveals a piece of the history of our ancestors .

- Large burial ground discovered in Wels . Website of the ORF Upper Austria, notification from August 12, 2005.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Maria-Barbara von Stritzki: Art. Grabbeigabe. In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Vol. 12, Stuttgart 1983, Col. 429-445; Helmut Geißlinger, Eckardt Meineke, Giesela Schiller: Art. Grave and grave custom. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Vol. 12, pp. 491-515; Kurt Reindel: grave goods and the church. In: Journal for Bavarian State History . No. 58, pp. 141f.

- ↑ Cf. Ronald Knöchlein: The row grave field of Waging am See , p. 70, quote: A properly organized form of Germanic religiosity with sanctuaries and priests ... had already become part of a strange world for the people behind the row graves.

- ↑ Ronald Knöchlein, The row grave field of Waging am See, page 66, quote: Correspondingly, the rich equipment of the Waging men's graves 66 and 77, in the period between 610 and 640, in the eyes of contemporaries did not contradict Christian ones Emblems in the form of gold leaf crosses, ...

- ↑ Ronald Knöchlein, The row grave field of Waging am See, page 60, quote: It is a death custom adopted from Lombardy Italy. The crosses are made of very thin, foil-like sheet of gold that has not been used for practical purposes and were sewn onto the robes of the deceased before they were buried.

- ↑ Archaeological State Collection Bavaria, "Karfunkelstein und Silk" , 2010

- ↑ Early Middle Ages - Merovingian period . Website of the Archäologische Verein im Landkreis Freising eV. Accessed on October 12, 2012.

- ↑ http://www.unser-vilstal.de/index.php?cat=59&subcat=81

- ↑ Large burial ground discovered in Wels . ORF Upper Austria website , August 12, 2005. Accessed October 12, 2012.