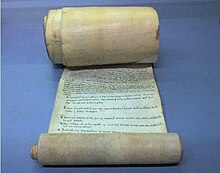

Scroll

| Storage medium Scroll

|

|

Joshua scroll |

|

| General | |

|---|---|

| lifespan | if properly treated, thousands of years |

| size | usually unrolls several meters |

| Weight | usually a few hundred grams |

| origin | |

| predecessor | Clay tablet |

| successor | Code |

The scroll (also called book scroll or volume ) is a labeled papyrus or parchment sheet in roll form and the typical book form of antiquity. In late antiquity , the codex prevailed as a new form of book , for which parchment was increasingly used and whose shape largely corresponds to today's paper book .

In the Middle Ages , parchment scrolls were mainly used for administrative registers. The term Rotulus (Latin) and the German terms Rodel and Rödel derived from it are also used for this (the word Rolle also comes from the Latin rotulus and rotula ). Occasionally there were rotuli made of paper (for example a paper rotulus about the process expenses of the Essen monastery 1353-1355).

Origin and Distribution

Ancient scrolls

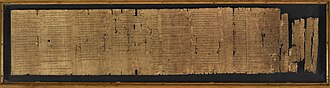

Ancient scrolls are preserved from many cultures, the oldest come from Egypt. In ancient Egypt , the papyrus scroll has been around since the 4th millennium BC. Known.

The scroll was adopted from Egypt in Greece . According to Herodotus , the papyrus has replaced leather as a writing material . In Greece the papyrus roll was since the 6./5. Century BC Widespread in Rome not before 3rd / 2nd Century BC Chr.

The scrolls were largely superseded in the 4th and 5th centuries by the Codex , a bound block of parchment or papyrus sheets that essentially corresponds to today's book form. In part, the role form for literary texts persisted into the 6th century, especially in Eastern Europe . The scroll was still a symbol of classical education ( paideia ) in the 6th century .

When Egypt fell to the Arabs in the 7th century, papyrus also became rare in the Byzantine Empire . Documents written on papyrus rolls have survived until the 11th century.

Sillybos (Greek, Sing. Sillybos ; Latin, tituli or indices ) were used to indicate the title and author of a work , which were strips of parchment that were attached to the scrolls of antiquity.

Rotuli in the Middle Ages

In the European Middle Ages literary, liturgical and scientific books were produced almost exclusively as codices. Scrolls came into use in western Europe via Byzantium from the 9th century . They spread especially in England since the 12th and 13th centuries. Century in the administration, z. B. for accounts and property registers (see also documents from the Middle Ages and early modern times ) and were then also used for works of genealogical or historical content.

In the German Middle Ages, manorial registers in particular were kept as rotuli. This is also where the German words Rodel and Rödel refer, which were mainly used to describe Urbare . The citizen role (also citizen protocol, citizen registration book , libri civium, burbok or citizen book) recorded all persons with granted urban civil rights . The Alemannic parlance uses the term toboggan synonymously to this day . The names differ depending on the purpose, so there was a patch toboggan or a covered toboggan . The use of rotuli for list-like directories also derives from modern names such as Stammrolle , Handwerksrolle and Musterrolle .

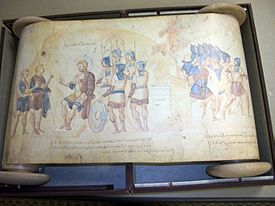

In southern Italy , rotuli are used as liturgical manuscripts for the Exsultet ( Exultet scroll ). These richly illustrated manuscripts align the images and text the other way around, as the rotulus was rolled over the edge of the desk when reading it so that it hung down on the outside. On the outside, the images were then properly aligned for the audience, while the editor saw them upside down. In England , the Rotulus was used for a long time for the sheriff's accounts to the head office ( pipe rolls ) .

Until the early modern period , Benedictine monasteries in particular had the so-called Totenrotel made from pieces of parchment stuck together. With them, other convents were informed of the death of their own monks for the purpose of prayer .

Usage today

Today very few texts are carried out as scrolls. In Jewish worship, the tradition of the handwritten scroll ( Hebrew מגילה Megilla ) to this day received in the Torah scroll , for the megillot and other biblical books. Since the biblical scrolls contain the name of God, they are treated with special care and must not be touched with the hands. In Judaism there are also copies in codex form. These are not intended for the worship service, but as templates for copying.

Manufacturing

materials

The scroll mostly consisted of papyrus and was the predominant book form in antiquity until the 4th century AD. In the library of the Attalids in Pergamon are in the 2nd century BC BC. Parchment rolls attested to in literature. In late antiquity , the codex prevailed as a book form and parchment as a writing material. Scrolls made of leather or parchment were much rarer. These writing materials are generally more durable than papyrus, which is particularly sensitive to the influence of moisture.

Leather rolls were used by the Egyptians, Assyrians , Persians and Jews , among others . The leather scrolls with religious Jewish texts found in Qumran in 1947 are of great importance (see Dead Sea Scrolls ).

processing

A papyrus roll is created by gluing individual sheets of paper together (singular kollema ; plural kollemata ). On average, a roll consists of around 20 leaves and, with a leaf width of around 25–30 centimeters, reaches a length of around 6–10 meters.

When gluing the papyrus sheets, attention was paid to a uniform grain direction. On the inside, the writing side of the roll (recto side), the fibers of the leaves run horizontally, because when writing the kalamos it is easier to guide them parallel to the grain. On the outside (verso side), where the fibers run vertically, they prevent the calamos from running.

The first sheet, the protokollon , is the only sheet with a vertical grain on the inside. It is left blank when writing and serves as a protective cover for the papyrus roll. The fact that a broad field remains free at the end of the role is also attributed to aesthetic intent and conservational considerations.

labeling

Inks of various formulations were used for writing . Prescribed positions could be erased with a sponge and overwritten again. However, papyri that have been completely washed off and rewritten hardly come across - unlike overwritten parchment (see Palimpsest ).

The title of the text is usually noted at the end of the roll ( explicit ). In addition, it is attached to the outside of the closed roller in the vertical direction. Since several roles are often required for a single work (the structure of extensive ancient texts in "books" is due to this), the author's name and the title of the work must be noted at the beginning and at the end of each role.

Papyrus rolls were sometimes also written on the back (verso side), especially afterwards when they were used a second time, when rolls were removed from the archives of the authorities as waste . Then the back was used, for example, for business records or - much more often - for private copies of literary texts. Such roles described on both sides are called opisthographs if the second inscription comes from the same hand or from the same context. The opisthographer (the described outside) is usually younger than the text on the inside of the scroll and thus provides a term for it ante quem . If roles contain dated administrative texts, the opisthographers can be precisely timed.

In contrast, it seldom happened that a text was started on the inside and continued on the outside (at most in the case of notes or material collections by authors).

Typeface

Literary roles (volumes) as well as the Torah scrolls were described parallel to the longitudinal edge in equally wide columns (Greek selis ; Latin pagina , which, however, usually means page ) with a uniform number of lines, which are separated from each other by spacing (intercolumn). A wide strip remains free above and below the columns, on the one hand to protect the font from damage and on the other hand to ensure a pleasing appearance. In contrast to this, the lines of writing in the rotulus , which was particularly common in the Middle Ages, run across the longitudinal edge. Short lines are considered a high quality feature in typeface. The indispensable conceptual distinction between volume and rotulus according to the course of the lines is repeatedly disregarded, sometimes even in specialist literature, which then gives rise to misunderstandings.

On Greek papyri, scriptura continua is used within the lines, i.e. without spaces or separators between the individual words. In later literary papyri there are various diacritical marks such as B. Colons to clarify sections of thought. They go back to the text-critical work of the grammarians in the large Hellenistic libraries (e.g. Alexandria ). Such signs, the use of certain abbreviations as well as different forms of writing provide important information about the dating of papyri in palaeography . In contrast to Greek papyri, Latin papyri have more points of separation between the words.

Illustrations are rare in papyrus rolls. Wherever they appear, outlined figures (outline drawings) are usually framelessly inserted into the font block of the column. From here the term role style is derived in the terminology of book illumination .

handling

Read

Both hands are required to read a scroll. The text to be read is rolled out with the right hand, while the text that has already been read is rolled up with the left hand, provided that it is not simply left hanging loosely. For Hebrew scrolls, as used in synagogue worship, the reading direction is reversed.

As a rolling aid, a wooden stick (Greek omphalos ; Latin umbilicus = navel) could be inserted into the roll or glued to the right edge of the last kollema . For religious reasons, a Hebrew Bible scroll must not be touched with the hands, but only by the handles. A small, often artistically designed, pointer is used for reading ( Jad , literally "hand"). After reading it, the role must be rolled back again.

The Latin term volume is derived from this type of handling (literally “roll”, from volvere “roll”, “wälzen”).

storage

Rolls were placed in baskets, jugs, or pots, or stacked lying on wooden racks, shelves, or cupboards. For transport purposes in particular, they could also be kept in box-shaped or chest-shaped containers (book cases). Such containers (Greek kibotos , kibotion , kiste , teuchos ; Latin capsa , scrinium ) are known from numerous pictorial representations. A cylindrical shape was typical in the Roman world. In the sculpture it appears as an attribute of erudition and literacy as a statue support next to the sitter's foot.

In order to be able to specifically access stored rolls, they were provided with small strips of parchment (Greek silliboi , Latin tituli ) on which the author's name and book title were noted. These strips were attached to the top of the roll so that they could be read even when the rolls were densely packed.

In comparison to the codices written on both sides, scrolls require considerably more space for storage, as they are only written on one side and cannot be stacked. They also catch fire faster in a fire.

See also

literature

- Giulio Battelli : Rotolo liturgico, in: Enciclopedia Cattolica X, Città del Vaticano 1953, pp. 1399–1402.

- Horst Blanck: The book in antiquity. Beck, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-406-36686-4

- Hubert Cancik and Helmuth Schneider (eds.): The new Pauly. Encyclopedia of Antiquity. Vol. 10. Metzler, Stuttgart a. Weimar 1997, ISBN 3-476-01480-0

- Guglielmo Cavallo : Rotoli di Exultet dell'Italia meridionale, Bari 1973.

- Severin Corsten, Stephan Füssel and Günther Pflug (eds.): Lexicon of the entire book system. Vol. 6. 2., completely revised edition. Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-7772-0327-0

- Umberto Dallari: I Rotuli dei Lettori Legisti e Artisti dello Studio Bolognese dal 1384 al 1799. Bologna 1899.

- Etienne Doublier, Jochen Jorendt, Maria Pia Alberzoni (eds.): The rotulus in use. Possible uses - design variance - interpretations . Böhlau, Cologne 2020, ISBN 978-3-412-51802-8

- Helmut Hiller and Stephan Füssel: Dictionary of the book. Sixth, fundamentally revised edition. Klostermann, Frankfurt a. M. 2002, ISBN 3-465-03220-9

- André Jacob: Rouleaux grecs et latins dans l'Italie méridionale, in: Recherches de codicologie comparée. La composition du codex en Orient et en Occident. Texts édités par P. Hoffmann. Index rédigés by C. Hunzinger. Paris, École normal supérieure, 1998, pp. 69-97.

- Otto Mazal : Greco-Roman Antiquity. Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, Graz 1999, ISBN 3-201-01716-7 (History of Book Culture; Vol. 1)

- Thomas Meier u. a. (Ed.), Materiale Textkulturen. Concepts - Materials - Practices (Series of publications of the Collaborative Research Center 933 1), De Gruyter, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-11-037128-4

- Gabriel Nocchi Macedo: The Parchment Roll: a Forgotten Chapter in the History of the Greek Book . In: Polymatheia: studi classici offerti a Mario Capasso. Lecce 2018, 319–342. ISBN 978-88-6760-379-4

- Richard H. Rouse: Roll and Codex, in: Paläographie 1981, ed. v. Gabriel Silagi, Munich 1982 (Munich Contributions to Medieval Studies and Renaissance Research 32), pp. 107–123.

- Leo Santifaller : About late papyrus rolls and early parchment rolls, in: Fs. For Johannes Spörl, 1965, pp. 117-133.

- Birgit Studt : usage form of medieval rotuli. The word on the way to writing - the writing on the way to the picture, in: Vestigia Monasteriensia. Westphalia - Rhineland - Netherlands, ed. v. Peter Johanek, Mark Mersiowsky u. Ellen Widder, FS f. Wilhelm Jansen, Bielefeld 1995 (Studies on Regional History 5), pp. 325–350.

- Michaela Zelzer : From the role to the codex, in: Text als Realie, ed. v. Karl Brunner, Gerhard Jaritz, Vienna 2003 (meeting reports d ÖAW-PH 704; publications by the Institute for Reality Studies of the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Age 18), pp. 9–22.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Duden online: Toboggan

- ↑ Duden online: role , see details under origin.

- ↑ Herodotus, 5.58

- ↑ Cf. Enno Giele et al.: Roles, scrolling and (de) folding , in: Thomas Meier u. a. (Ed.): Materiale Textkulturen. Concepts - Materials - Practices (series of publications of the Collaborative Research Center 933 1), De Gruyter, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-11-037128-4 , pp. 677-693, especially pp. 686 f.

- ^ Totenrotel in PW Hartmann's art dictionary

- ↑ The Esther Scroll in Florence Information from the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana (Italian)

- ↑ See Enno Giele et al. a .: Rolling, scrolling and (un) folding , in: Thomas Meier u. a. (Ed.): Materiale Textkulturen. Concepts - Materials - Practices (series of publications of the Collaborative Research Center 933 1), De Gruyter, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-11-037128-4 , pp. 677–693, especially pp. 677–681.