Rudolf Boehm (pharmacologist)

Rudolf Boehm , actually Rudolph Albert Martin Boehm (born May 19, 1844 in Nördlingen , † August 19, 1926 in Bad Kohlgrub , Upper Bavaria) was a German physician and pharmacologist .

Life

Son of a doctor, he studied medicine in Munich and Würzburg and received his doctorate in medicine in Würzburg. (Information that he also studied in Leipzig and received his doctorate there is incorrect.) At the father's request, he first chose a clinical subject and became an assistant in the psychiatric clinic at the Würzburg Juliusspital . The director of the clinic, Franz von Rinecker , a versatile scholar, recognized Boehm's interest in experimental work and recommended him to deepen his physiological training with Carl Ludwig in Leipzig. Here he met the discoverer of nucleic acids Friedrich Miescher and the pharmacologist Oswald Schmiedeberg , who was already a professor in Dorpat , today's Tartu in Estonia. In Leipzig, Boehm began his studies on cardiac toxins , in which he examined the effects of alkaloids such as muscarine , nicotine and veratrine on frog hearts and with which he completed his habilitation in physiology with Adolf Fick in Würzburg in 1871 . In 1872 he took over the chair of pharmacology, dietetics and the history of medicine in Dorpat from Schmiedeberg, who was called to Strasbourg that same year . From 1881 to 1884 he was Professor of Pharmacology in Marburg , and from 1884 until his retirement in 1921 Professor of Pharmacology in Leipzig. Here, according to his plans, an exemplary institute was built for the time, which was destroyed in the Second World War. In 1888 Boehm was elected a member of the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina . Since 1886 he was a full member of the Saxon Academy of Sciences .

research

General

Boehm has studied the pharmacology and toxicology of many substances. He dealt particularly intensely with plants in which, following the example of the discoverer of morphine Friedrich Sertürner, he searched for the effective ingredients. This included, for example, the worm fern . In 1920, in the most important manual in his field, the Handbuch der Experimental Pharmakologie , now the Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology , edited by his student Arthur Heffter , he wrote the chapters on the aconite group (ingredients of the blue monkshood ), veratrine and protoveratrine (ingredients of the white Germer , Veratrum album) as well as curare and curare alkaloids . Otto Krayer started out from Boehm's work on the ingredients of the White Germer in his further research into these substances.

Curare

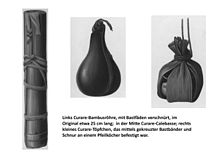

Best known, and still having an impact in practical medicine today, was Boehm's research on curare. He divided the curare preparations into three types: “The South American arrow poison curare ... is manufactured by Indian tribes in equatorial South America in the river areas of the Orinoco and Amazon and is very irregularly supplied, recently again very sparsely, in European trade. According to the packaging and also the chemical components, three types can be distinguished: 1. Calabash curare (in pumpkin skins, gourds), 2. Pot curare (in small clay pots), 3. Tubocurare (in bamboo tubes). "

In 1912, the surgeon Arthur Läwen in Leipzig performed muscle relaxation for the first time during an operation on a person . He wrote: “A great disadvantage of superficial anesthesia is that the patient excessively tenses the abdominal muscles, especially when suturing the abdominal wall, so that a proper layer suturing is very difficult. ... It is precisely this abdominal tension that is to blame for the fact that deep anesthesia is often required in the last stage of the operation. This again brings the risk of overdosing into the vicinity. I have now tried to prevent this tension in the abdominal muscles in other ways. I used curarin , the active substance made by Boehm from the curare preparations. Curarin has the great advantage over curar drugs of being a precisely dosed preparation, in which the same dose always corresponds to the same effect with absolute reliability. With the usual curare preparations I would never have dared to experiment on humans. ... The effect of the abdominal wall suture (was) very clear and pleasant. … Unfortunately, the curar drug is currently not available in sufficient quantities. ” Perhaps it was this lack of supplies that made Läwen's thoughts and observations forgotten: They came too early for the circumstances of the time. In any case, the American doctors who introduced curare preparations into anesthesiology for all future in 1942 apparently no longer knew anything about him.

On the basis of Boehm's work, the chemical structure of tubocurarin was finally clarified in 1935 : “The South American arrow poisons known as curare were shown by Boehm ... to be of three kinds, distinguished primarily by their containers and secondarily by their different chemical characteristics. … An opportunity arose of examining the three types of curare described by Boehm, and I have been able to confirm the fundamental soundness of his observations. “ The Swiss-Italian pharmacologist and recipient of the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine 1957 Daniel Bovet ruled in 1948 (from the French): "Even today one has to start from Boehm's classification if one wants to get an overall picture of the geographical origin, the forms of trade and the use of the curar preparations."

The Boehm School of Pharmacology

The largest pharmacology school in the German-speaking area goes back to Rudolf Buchheim and Oswald Schmiedeberg, the second largest to Rudolf Boehm. His immediate students included Arthur Heffter (1859–1925), first professor in Bern , Walther Straub (1874–1944), first professor in Marburg, Oscar Gros (1877–1947), first professor in Halle , Josef Schüller (1888–1968 ), Professor in Cologne , and Fritz Külz (1887–1949), professor first in Kiel . Among the younger ones, only Otto Krayer (1899–1982) and Melchior Reiter (1919–2007) are mentioned; Krayer described the Boehm School in a book that Reiter published in 1998.

In 1999 the Pharmacological Institute Leipzig named itself the Rudolf Boehm Institute for Pharmacology and Toxicology .

Web links

- Literature by and about Rudolf Boehm in the catalog of the German National Library

- Rudolf Boehm in the professorial catalog of the University of Leipzig

- Overview of Rudolf Boehm's courses at the University of Leipzig (winter semester 1884 to summer semester 1914)

- Rudolf Boehm on uni-leipzig.de

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Matthias Hennig: Life and work of the pharmacologist Rudolf Boehm (1844-1926). Dissertation. Leipzig 2000.

- ↑ R. Boehm: Studies on cardiac toxins. Stubers bookstore, Würzburg 1872.

- ^ Johannes Büttner: Boehm, Rudolf. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 2, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1955, ISBN 3-428-00183-4 , p. 379 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Member entry of Rudolf Boehm at the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina , accessed on October 12, 2012.

- ^ Members of the SAW: Rudolf Boehm. Saxon Academy of Sciences, accessed on September 30, 2016 .

- ↑ W. Straub: The Filixgruppe. In A. Heffter (Ed.): Handbook of experimental pharmacology. Second volume. Springer, Berlin 1924, pp. 1548–1562.

- ↑ a b R. Boehm: Curare and Curarealkaloide. In: A. Heffter (Hrsg.): Handbuch der experimental Pharmakologie. Second volume. Springer, Berlin 1920, pp. 179–248.

- ^ R. Boehm: Veratrin and Protoveratrin. In A. Heffter (Ed.): Handbook of experimental pharmacology. Second volume. Springer, Berlin 1920, pp. 249-282.

- ↑ R. Boehm: The aconite group. In: A. Heffter (Hrsg.): Handbuch der experimental Pharmakologie. Second volume. Springer, Berlin 1920, pp. 283-319.

- ^ Rudolf Böhm: The South American arrow poison curare in chemical and pharmacological relation. In: Treatises of the mathematical-physical class of the royal Saxon society of science. 20, 1895, pp. 201-238 and 24, 1897, pp. 3-52.

- ↑ A. Läwen: About the connection of local anesthesia with anesthesia, about high extradural anesthesia and epidural injections of anesthetic solutions in tabular gastric crises. In contributions to clinical surgery. 80, 1912, pp. 168-189.

- ↑ Harold R. Griffith, G. Enid Johnson: The use of curare in general anesthesia. In: Anesthesiology. 3, 1942, pp. 418-420.

- ↑ Harold King: Curare alkaloid. Part I. Tubocurarine. In: Journal of the Chemical Society. 1935, pp. 1381-1389.

- ↑ Wolf-Dieter Wiezorek, Martin Müller: Rudolf Boehm's contribution to the research of the Kurare. In: NTM series for the history of science, technology and medicine. 12/2, 1975, pp. 97-107.

- ^ Jürgen Lindner, Heinz Lüllmann: Pharmacological institutes and biographies of their directors. Editio Cantor, Aulendorf 1996, ISBN 3-87193-172-1 .

- ^ Otto Krayer: Rudolf Boehm and his school of pharmacology. Zuckerschwerdt, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-88603-635-9 .

- ^ Website of the Rudolf Boehm Institute for Pharmacology and Toxicology with photos of Boehm

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Boehm, Rudolf |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Boehm, Rudolph Albert Martin |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German physician and pharmacologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 19, 1844 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Nordlingen |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 19, 1926 |

| Place of death | Bad Kohlgrub , Upper Bavaria |