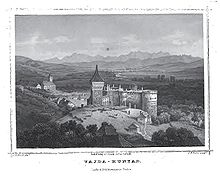

Hunedoara Castle

| Hunedoara Castle | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Hunedoara Castle |

||

| Alternative name (s): | Hunedoara Castle, Corvinilor Castle, Corvinian Castle, Corvinus Castle, Corvinesti Castle, Corvin Castle, Iron Market Castle, Black Castle, Vajdahunyad Castle, Hunyadi Castle | |

| Creation time : | 14th to. 15th century | |

| Castle type : | Höhenburg, rocky location | |

| Conservation status: | Received or received in substantial parts | |

| Standing position : | Princes | |

| Place: | Hunedoara , Romania | |

| Geographical location: | 45 ° 44 '57 " N , 22 ° 53' 18" E | |

|

|

||

The Hunedoara Castle (also Hunedoara Castle, German Eisenmarkt Castle ; Romanian Castelul Corvinilor or Castelul Huniazilor ; Hungarian Vajdahunyadi vár ) is one of the most important secular buildings in Transylvania . The rock castle was built on the remains of a fortification from the 14th century. It is located on a limestone rock in the middle of an industrial complex in the southwestern part of the city of Hunedoara (iron market) in Romania .

The Grade II listed castle bears another name ( Castle Corvinilor , stronghold of Corviner , castle Corvinus , Corvinesti Castle , Castle Corvin , castle Eisenmarkt , Black Castle , Vajdahunyad Castle , Castle Hunyadi ), which refer to their location or their owners.

After 1440, the Hungarian statesman and military leader Johann Hunyadi had an existing fortification converted into the ancestral seat of the Hunyadis . In the second construction phase after 1458, the castle was expanded under King Matthias Corvinus . At the beginning of the 17th century, Prince Gábor Bethlen carried out further major changes to the building. Today's castle has a mixture of different architectural styles .

The castle was first in Austria from 1724 and has been in the Romanian state since 1918. Today a museum has been set up in the building. The castle is also used as a film set . A large number of Romanian and international film productions were shot on the castle grounds.

history

According to a document dated October 18, 1409, King Sigismund of Luxembourg awarded the royal territory of Hunedoara (iron market) with a fortification to the noble Vojk (Voicu) Corbu . This probably immigrant boyar from Wallachia previously served as a knight at the king's court. At that time, the Transylvania region belonged to the Kingdom of Hungary .

Resident and owner of the castle

From the builder of the castle to Matthias Corvinus

Johann Hunyadi was the builder of the castle. He established it at the time when he was holding the office of governor or voivode (ung. Vajda) of the Kingdom of Hungary. The place of birth of this man as well as his origin are uncertain. He was the supposed son of the nobleman Vojk (Voicu) Corbu and Elisabeth Morzsinay. A folk legend also made him the son of King Sigismund of Hungary. The statesman and military leader from Transylvania was one of the most important political and military leaders of the 15th century in Europe.

Hunyadi's first son Ladislaus Hunyadi , who was born in the castle in 1433, became the owner of the property between 1456 and 1457. After his conviction and beheading on March 16, 1457 the property went to Matthias Corvinus, the second son of Johann Hunyadi and Erzsébet (Elisabeth) Szilágyi von Horogszeg. As a result of his activities, King Mathias Corvinus only stayed temporarily in the castle. In 1490 the king died.

Time after Matthias Corvinus

Matthias Corvinus' illegitimate son Johann Corvinus then became the new owner of the castle. He died in 1504 at the age of thirty-one. His widow, Beatrice de Frangepan , became the new lord of the castle as guardian of the half-orphans Christoph and Elisabeth. In the following year their son Christoph died and in 1507 their daughter Elisabeth died. Beatrice de Frangepan married Georg von Brandenburg after the mourning period ended in 1509 .

The Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach thus became the sole heir of the properties of Hunedoara Castle. However, Georg von Brandenburg handed over the castle and the goods belonging to it to the noble Gaspar and Nicolaus Török von Enning before his death. In 1526 the property was already in the hands of the Töröks.

Ownership then changed within the Török family, initially from Gaspar and Nicolaus Török to Valentin Török . After Valentin Török's death in the dungeon of Yedikule , a Capitaneus Georg Badas married the widow. He also obtained the rights to part of the castle area. Valentin's sons Johann and Franz Török von Enying later regained full possession of the paternal inheritance through the payment of a severance payment of 12,000 thalers to Georg Badas.

Johann and Franz Török each left a son, Johann a son of the same name, Franz left Stefan Török, mentioned several times in Transylvanian history. At the beginning of 1605, Stefan, as the last male family member of his name, pledged the castle to the equestrian general and later Prince of Transylvania, Gábor Bethlen . However, the seizure money of 12,000 guilders was not collected from Stefan's heirs until 1618 because his sister Catharina was still alive after Stefan's death in 1612.

From Gábor Bethlen to the death of Catharina Zólyomi

Gábor Bethlen therefore only took possession of the goods complex after Catharina Török's death as a fallen crown property . Prince Bethlen and his wife Susanna Karolyi, who died in 1626, had two sons, Gabriel and Michael Bethlen, who died early. After his second marriage to Katharina von Brandenburg did not result in any descendants, the prince rearranged his inheritance matters. He found an heir in his relatives. His brother Stefan Bethlen and his wife had four sons and three daughters. Gábor raised his brother's son of the same name and adopted him in place of his son. After Gabor's death on November 15, 1629, Stefan Bethlen the Younger took possession of the castle and goods of Hunyad by virtue of a will.

A year later, Stefan Bethlen, the younger, died in his castle in Ecséd . Stefan's wife then compared herself with Stefan's father and his still living son Peter about the property and her inheritance claims. After Peter Bethlen died on August 3, 1646 and his father followed him two years later, the property passed to his daughter Catharina Bethlen. Their inheritance claims have been challenged several times.

Catharina was married to David Zólyomi, who himself tried to get into the Transylvanian princely chair. As a result, he was convicted of high treason on August 21, 1633 and then imprisoned in the Kővár Castle prison . Urgent pleading and urging meant that Catharina was later allowed to share the prison with her husband in which she gave birth to her daughter Kövari Catharina. During her voluntary imprisonment, she transferred part of the property to Stefan Tököli, her niece Maria's husband, in order to maintain the security and order of the property. After the death of her husband in 1651, Catharina Bethlen returned to Hunedoara. She then tried to get back the goods confiscated in the high treason trial, which she partially succeeded in doing. She lived there until 1666. After that, her inheritance fell to her children Maria and Nikolaus Zólyomi, who then shared the property. For unexplained reasons, her daughter Kövari Catharina was not mentioned in the drafting of the partition agreement.

From Nikolaus Zólyomi to the transition to Romanian ownership

The eleven-point contract was challenged in 1667 by Nikolaus Zólyomi, because of an inserted clause in favor of Stefan Tökölis, before the Diet held at Marosvásárhely . The lawsuit ended in a compromise. Afterwards Nikolaus Zólyomi married a sister of George I. Rákóczi for political reasons in order to end the existing hostilities between the two noble families Bethlen and Rákóczi . After separating from his unloved wife, however, he took sides against Georg II. Rákóczi . In a battle with Ákos Barcsay, he besieged the castle in Hunedoara to avenge Zólyomi's infidelity. After the siege, Nicholas was captured and imprisoned in Hungary until June 1660. After his imprisonment, Nikolaus' political activities continued during the dispute for the throne between Johann Kemény and Michael I. Apafi . For this reason he was charged with high treason and held captive in the fortress of Făgăraș for nine months until his successful escape on March 14, 1664 . Nikolaus Zólyomi used his newly won freedom to regain complete possession of his goods. He therefore contacted the Turkish commanders around Sultan Mehmed IV , who then asked Michael I. Apafi to return his property to Michael.

The death of Zólyomi in 1671 was therefore welcome news for Prince Michael I. The property now came completely into Michael’s hands. Emmerich Thököly later acquired the property from Michael I. Michael II Apafi , Michael I Apafi's son, then became the owner of the castle. When he died on February 1, 1713, his widow Catharina Apafis came into possession of the property. She died in 1724, after which the castle fell to the state treasury.

From this time on, Hunedoara Castle remained in state ownership: from 1724 to 1867 initially owned by Austria and then from 1867 to 1918 by Austria-Hungary . The building has been in Romanian ownership since 1918 .

Researched stories and legends

There are several tales and legends about the castle. In addition to other castles in Transylvania, it is also traded as "the real Dracula's castle", but Vlad III. Drăculea not possessed them. He only visited the then owner and ally Matthias Corvinus at the castle. In 1462, Vlad III. flee to Transylvania after a crusade against the Turks. On his escape he found protection with Matthias Corvinus, the then King of Hungary, who later had Drăculea imprisoned for twelve years in Visegrád Castle and probably temporarily in Hunedoara Castle for alleged treason .

The legend of the well

According to the story, the 28-meter-deep castle well in the courtyard of the castle was dug by three Turkish prisoners, who were promised their freedom if they dig until they reached the water. When they had completed their task after 15 years of work, their clients refused to keep their promises. According to the legend, the wrongly translated inscription of the prisoners "You may have water, but hardly any feelings" on a castle wall near the well testifies to the bitter disappointment of the Turks.

The legend of the raven

The Corvin family coat of arms depicts a raven with a gold ring in its beak. There are various stories and an allegorical fresco in the castle about the heraldic bird with a ring. A legend tells that Johann Hunyadi was the illegitimate son of King Sigismund of Luxembourg and his mother Elisabeth Morzsinay. Subsequently, Sigismund is said to have married Elisabeth to the nobleman Vojk (Voicu) Corbu.

As a sign of identification, Sigismund gave his lover a ring as a gift for the unborn child. During a trip, a raven stole the glowing ring while eating. Johann Hunyadi then killed the raven and won his ring back. To commemorate this event, he later chose the raven as a symbol for his seal. According to another popular story, Johann Hunyadi's son Matthias I called himself Corvinus (Latin for raven) because he derives this name from the Hunyadi family coat of arms.

Building history

Predecessor castle

The building, which was built on a previous castle, has undergone a lot of conversion and renovation work as well as extensions over the course of time, each in the style typical of its era. Some historians date the first stone fortifications to the 14th century. Others, however, assume the 15th century. This weir system was elliptical in shape with pointed ends. The walls were up to 2 meters thick. Limestone, gravel and dolomite were used. Research from the First World War revealed that the fortress had a triangular tower.

After being awarded to Vojk (Voicu) Corbu, the castle also formed the central location of Hunyad County . It was a link in a chain of earlier defensive structures that were located close to the national border. Such castles were built according to the strategic requirements of the time, especially against the background of the Turkish threat .

Ancestral seat of the Hunyadi

The castle, commissioned by Johann Hunyadi after 1440, is a masterpiece of Gothic secular architecture, reminiscent of the French castles of that time. Hunyadi had the fortress converted into his ancestral castle. When exactly he came into his inheritance is unknown. However, he then appointed a castle bailiff who was not known by name and who defended his rights during his absence.

In 1446, when Johann Hunyadi became imperial administrator of Hungary, the chapel, which was begun in 1442, stood. It forms the oldest part of the ancestral castle of the Hunyadi. In the first construction phase, more walls were built around the already existing fortress. In addition, the round towers Pustiu, Tobosarilor and Capistrano as well as the rectangular portal towers Nou de poarta and Vechi de poarta on the northwest and southeast side of the castle were built. The representative residential wing and the knight's hall below from 1452 were built in the western part. A long gallery connected the newly built Njebois tower with the castle.

Johannes Hunyadi lived above the knight's hall in close proximity to his friend Johannes von Capistrano - an itinerant preacher - who lived in a cell in the northwest corner bastion. Later lords of the castle lodged in the part of the castle above the main gate. The living area was near the dungeon with its " Iron Maiden " located under the knight's hall . Hunyadi's first son Ladislaus Hunyadi is said to have been born in 1433 on the stone seat in the face of the second northern bay window of the castle.

The Matia-Loggia, also known as Matthias Wing, was not built until the second construction phase under King Matthias Corvinus after 1458. In this phase of construction, the eastern extension on the north side of the castle and the access bridge rising from the deep valley floor, that of five brick high pillars is supported. The construction work in the Renaissance style was completed around 1480 under Matthias Corvinus. The year 1480, carved in stone above the main gate, confirms this assumption. The Hunyad castle area became a county a year later .

Restoration and remodeling in the 16th and 17th centuries

In 1534 the castle was besieged, conquered and partially destroyed by Emerich Csibak, a zealous follower of Zápolyas, as a result of disputes between the then lord Valentin Török and Prince Johann Zápolya . Shortly thereafter, Valentin Török changed his mind in favor of Zápolyas. As a result, in 1535 Zápolya confirmed Valentine's possession of the castle. He also had the building of Csibak restored. In 1599, Mihai Viteazul briefly gained sovereignty over Transylvania. In the same year, part of the castle and the neighboring town of Hunedoara were set on fire by Michaels Wallachians during battles .

At the beginning of the 17th century, Prince Gábor Bethlen came into possession of the castle. Gábor was the third owner who made major changes to the structure. Bethlen changed some areas of the castle for new civil and military uses. He built the Palatul mare and the white tower (Alb tower) on the east side, the ammunition bastion and the castle-like porch. Furthermore, the appearance of the interior of the chapel was fundamentally changed during the reign of Bethlen.

At the time of Peter Bethlen, a wall in front of it was built some distance from the castle bridge, then called the "barrier". It formed a kind of kennel around the so-called "Husarenhof". Several buildings stood in the protected space created by this surrounding wall. The first floor of the buildings, which had twenty-three loopholes, also served as a defense. The upper areas of the buildings were intended as apartments for court judges and stable masters. They were also used to house the Pandours .

Repairs and renovations by the 21st century

After the death of Catharina Apafis in 1724, the property fell to the tax authorities , who housed the mining office in the castle and used the building to store iron. A year later the castle was appropriately repaired. Further repairs were carried out in 1748 and 1754. In 1786, considerable damage to the roof came to light, which was repaired a year later.

Major repairs were carried out in 1817. In that year, Emperor Franz I and his fourth wife, Karoline Auguste von Bayern, went on a trip to Transylvania. After a three-day court camp in the castle, the emperor provided an amount of thirty thousand guilders for the most urgent renovations. As soon as the construction work was completed, however, lightning struck the chapel during a storm. This caused considerable fire damage to this and the surrounding structure.

Because of the poor condition of the castle as a result of the lightning damage, a public intervention by a Hunyad district mine inspector later took place. A report in the newspaper "Kedveskedőben" in June 1823 it resulted in a donation of Hunyader county . In the following years the castle could be restored.

Until the middle of the 19th century, the corridor of the part of the castle built in the 17th century and the wing built in the time of Johann Hunyadis were still in ruins. In addition, neither the tower nor the gallery were covered. The large old eastern bastion belonging to the main building was painted in red and white boxes. The castle had ninety-seven windows partially facing the castle courtyard and one hundred and eighty-one loopholes. Some of the adjoining Gothic windows were damaged by bullets. Several coats of arms had been carved out over the doors. There were rainwater openings at the corners of the wall. The courtyard was irregular and uneven. Rock formed the pavement. In addition to the farm buildings, there were two barns, a cattle shed and a poultry yard in the vicinity of the castle. After the repair work, the Hunyad District Office was housed in the castle rooms in 1852. However, it did not last long at this point.

Because on April 13, 1854, at 11 p.m., a fire broke out in the rooms on the north side, which increased in size, fanned by the strong north wind, and finally took over the whole building. Despite all the efforts, the fire could no longer be controlled. Because of this fire or the previous fires, the building is also called the "black castle".

Major renovation work on the ruins was only started in 1868 under the architect Ferenc Schulcz. Among other things, Schulcz began restoring the Gothic architecture in the knight's hall and restoring old sculptures. After his death, Imre Steindl , the builder of the parliament building in Budapest , continued the work until 1874 with a different emphasis. Steindl was obviously not interested in restoring the castle, but in renewing it. The architects Iuliu Piaczek and Antal Khuen carried out subsequent renovations. From today's perspective, the castle has suffered greatly from the inadequate restoration work of the 19th century.

In 1907 the architect Stefan (Istvan) Möler resumed the work that had been interrupted. A new phase of restoration began in 1956 on the basis of research by Oliver Velescu, a historian and architect of monument preservation. With the inclusion in the National Plan for Restoration in 1997, further construction, electrical and heating work as well as restoration and conservation work on frescoes and artistic objects were carried out. The Romanian Parliament provided funds for the repairs until 2004.

Description of the castle complex

The castle stands west of the old town of Hunedoara on a rock with an area of around 7,000 square meters. The building is enclosed on the west and south sides by the river Zlasti. A large moat surrounds the castle on the east and south sides. Parts of the upstream surrounding wall around the so-called "Husarenhof", which was built some distance from the castle bridge, are still preserved.

The dimensions of the castle vary in width between 10 meters (in the area of the Njeboisa wing) and 50 meters. In the north-south extension (including the Njeboisa tower) the castle is around 120 meters long. The premises of the castle and its outbuildings consist of five bastions, two halls, two halls, five anteroom, twenty-eight living rooms, nine oriel rooms, a bakery and a casemate on the east side . There is also the chapel and two terraces on the northern side.

The castle can be reached via two bridges. The main access on the west side is via a mighty wooden bridge standing on stone pillars, at the end of which there is a drawbridge that overcomes the Zlaşti gorge. Immediately in front of the bridge is a saint's house . The remains of a crumbled servants' house have been preserved directly below the main bridge next to the Zlaşti River. The small older wooden bridge stands on the east side of the castle. After crossing the main access bridge one arrives at the square portal tower (Turnul nou de poarta). The year 1480 can be seen above the main gate . At the end of the bridge, a few steps behind the statue of St. John Nepomuk , the inscription BEATVS IOANNES NEPOMVCENVS SANGVIN (IS) VNDA VT VE (STE) PVRPVRATVS HVNGARIAE (PATRONVS) can be read with the year 1664.

The former living and representative rooms are grouped around the manageable courtyard. The dungeon area and the ossuary are in the basement, the knight's hall and the chapel room on the ground floor. The family coat of arms of the Hunyadis with raven and ring is attached to the structure in several places. Some coats of arms are attached to doors or have been carved into the masonry above door entrances. In the knight's hall there are stone decorations with further coats of arms on the vaulted ceiling at the confluence of the arching edges. The most famous castle inscription is attached twice to a Gothic support column in the knight's hall. The writing, which already refers to the builder Johann Hunyadi, is carved on a column band once in Gothic and once in Latin script. The Latin inscription reads: Hoc opus fecit fieri Magnificus Johannes de Hunyad regni Hungariae gubernator. Anno Domini - MCCCCLII. The servants were also housed on the ground floor. The council chamber was on the first floor. The guests were accommodated on the 2nd floor or the attic in the southern part of the castle.

Adjacent to the main access bridge with the portal tower, the first terrace and the Loggia Matia (Matthias wing ) are added clockwise . The castle's most famous fresco from the 15th century can be seen in the Matthias wing. It shows three scenes in six pictures. The first scene in the lower part of the poorly preserved illustration shows a man with his right hand raised. In the opposite, better picture, a woman is holding an apple with a cross in her right hand. In the second scene in the middle part of the picture, a male person holds a ring in his right hand. The woman in the adjacent picture raises her left arm and turns her head away. Furthermore, a raven with a ribbon in its beak can be seen in the illustration. The third scene in the upper part of the image shows a gesture by the man. On the other hand, a pregnant woman is holding a loop with two rings in her left hand. The fresco matches another illustration that shows a hunting scene with a wild boar.

In the castle there are other frescoes from the era of Matthias Corvinus, who had the walls decorated with a series of paintings. In addition to frescoes with court games in the renaissance style, the surviving pictures from the raven legend also belong to it. The frescoes were discovered in 1883 by Stefan Möller, a professor of medieval building history from Budapest. Möller saw in this the evidence for the alleged descent of Hunyadis from King Sigismund. Other historians saw the genesis of the family coat of arms in the illustrations. According to the prevailing opinion of experts, the allegorical frescoes represent a coherent series of events.

Behind the loggia in the northern part of the castle is the Pictat Tower (also called Buzdugan Tower ) with the second terrace (Platforma de artilerie) . Between the two round towers Pictat and Tobosarilor, there is the chapel in the eastern part of the building and the castle fountain next to it. There is an old Arabic inscription on the buttresses of the chapel. For a long time the inscription was associated with the legend of the fountain . It was interpreted as: "You may have water, but hardly any feelings." The Arabic writing expert Mihail Guboglu translated the inscription differently. According to his translation, a prisoner probably chiseled the following sentence into the stone: "The person who dug this well is Hassan, who lives as a prisoner with the Giaurs, in the fortress next to the church." the letters GB (for Gábor Bethlen) and the years 1624 and 1629 .

This is followed by the Palatul mare and the old gatehouse (Turnul vechi de porta) . In between is the old access area with the small wooden bridge. The white tower (Turnul alb) stands right next to the bridge, on the south side of the castle the Pustiu round tower. The remote southern Njeboisa tower is connected to the castle via a 33-meter-long gallery standing on round, walled-up arched pillars, with a covered drawbridge at the end of the gallery. Adjacent to the gallery in the west are the Capistrano Tower and the Palatul mare with the knight's hall. Four ornate Gothic turrets adorn this area. From there you can reach the main bridge with the portal tower again.

Replicas of the castle

In the City Park in the Hungarian capital Budapest in 1896 which originated Vajdahunyadvár . The castle was initially made as a wooden model to illustrate the Hungarian architecture for the millennium celebration of the Hungarian people. Because of the great response, the Hungarian builder Ignác Alpár then built today's stone castle. The main part of the structure was modeled on the Hunedoara Castle (then Vajdahunyad Castle). Among other things, the Njeboisa tower and the ornate Gothic turrets were copied.

In addition, Hunedoara Castle was recreated in a Lego model between November 2006 and January 2007 .

Todays use

A tour of the castle including a museum visit or rental for commercial films is possible by prior arrangement. The castle is open to the public all year round. Special tours for individuals and groups are offered. The same applies to photo and film recordings. Medieval events and festivals take place regularly on the castle grounds.

In 1974 the castle museum was opened. At the beginning it housed medieval pieces. The collections were later expanded to include archeology, ethnology, decorative arts and old books. The museum has also been concerned with Dacian and Roman history since 1990 . The museum now has the CORVINIANA - Acta Musei Corvinensis, Ed. Muzeul Castelul Corvinilor, with ten volumes (Volume 1: 1994, Volume 2: 1995, Volume 3: 1996, Volume 4: 1997, Volume 5: 1998, Volume 6: 1999, Volume 7: 2000, Volume 8: 2001, Volume 9 : 2005, Volume 10: 2006).

The castle is often rented as a film set. A large number of Romanian and international film productions (artistic films, documentaries or commercials) have already been shot there. The productions include François Villon , Mihai Viteazul , Michelangelo Buonarotti , The Damned Kings , Vlad , Jacqou le Croquat , Blood Rayne , Martin Luther , Nostradamus (1994) and Heinrich the 8th. The Pro7 television series 48 Hours of Fear was also launched in 2002 shot in the castle. In the single video Don't waste your time by singer Kelly Clarkson , recorded in 2007, the castle can be seen several times as a backdrop.

The castle is also one of the locations in the 2018 film The Nun .

literature

- JSversch, JG Gruber: Hunyad. In: General Encyclopedia of Sciences and Arts. Gleditsch 1835. ( Online version at Google Books )

- Johann Gottfried Sommer: The Vajda Hunyad Castle in Transylvania. In: Pocket book for the dissemination of geographical knowledge. JG Calvesche, Prague 1847, pp. 1-10. ( Online version at Google Books )

- Wilhelm Schmidt: The ancestral castle of the Hunyad in Transylvania. Verlag Theodor Steinhausen, Hermannstadt 1865. ( Online version at Google Books )

- Oliver Velescu: Castelul de la Hunedoara. Ed. II. Editura Meridiane, Bucharest 1968.

- Gheorghe Anghel: Medieval castles in Transylvania. Bucharest 1973.

- Gustav Gündisch : Studies on the Transylvanian art history. Böhlau 1976, ISBN 3-412-01476-1 .

- Birgitta Gabriela Hannover: Discover Romania: Art treasures and natural beauties. Trescher Verlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-89794-104-5 .

Web links

- Castelu Corvinilor website (Romanian)

- Castelul Corvinestilor film on YouTube

Individual evidence

- ↑ Birgitta Gabriela Hannover: Discover Romania: Art treasures and natural beauties. 2007, p. 181.

- ↑ Mențiuni documentare , accessed on March 26, 2018 (Romanian).

- ↑ a b c d The Hunyadis. Brief history of Transylvania. ( mek.niif.hu , accessed March 27, 2009)

- ^ Johann Gottfried Sommer: The Vajda Hunyad Castle in Transylvania. 1847, p. 1.

- ↑ a b Proprietari , accessed on March 26, 2018 (Romanian).

- ↑ Wolfgang Huber: GEORG (the pious), Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 30, Bautz, Nordhausen 2009, ISBN 978-3-88309-478-6 , Sp. 472-484.

- ^ Wilhelm Schmidt: The ancestral castle of the Hunyad in Transylvania. 1865, p. 25.

- ^ Wilhelm Schmidt: The ancestral castle of the Hunyad in Transylvania. 1865, p. 31.

- ^ Wilhelm Schmidt: The ancestral castle of the Hunyad in Transylvania. 1865, p. 33.

- ^ Zólyomi Dávid. In: Magyar Életrajzi Lexicon 1000-1990.

- ^ A b Wilhelm Schmidt: The ancestral castle of the Hunyad in Transylvania. 1865, p. 55.

- ↑ Capper-online.de, accessed on March 6, 2009

- ↑ vlad-tepes.de, accessed on March 9, 2009

- ↑ a b Legendele castelului , accessed on March 26, 2018 (Romanian).

- ↑ Holger Richter: With raven and ring - The crossbows of the Hunyad era (15th century). In: The horn bow crossbow - history and technology. Verlag Angelika Hörnig, 2006, ISBN 3-938921-02-1 , p. 190.

- ↑ Rumaenien-info.at, accessed on March 1, 2009 ( Memento from November 7, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Plan of the castle at traseeromania.ro accessed on March 26, 2018.

- ^ A b Wilhelm Schmidt: The ancestral castle of the Hunyad in Transylvania. 1865, p. 13.

- ^ Horst G. Klein, Katja Göring: Romanian country studies. Narr, Tübingen 1995, ISBN 3-8233-4149-9 , p. 142.

- ^ Wilhelm Schmidt: The ancestral castle of the Hunyad in Transylvania. 1865, p. 16.

- ↑ Scurtă istorie , accessed on March 26, 2018 (Romanian).

- ^ Wilhelm Schmidt: The ancestral castle of the Hunyad in Transylvania. 1865, p. 26.

- ^ Johann Gottfried Sommer: The Vajda Hunyad Castle in Transylvania. 1847, p. 10.

- ^ Wilhelm Schmidt: The ancestral castle of the Hunyad in Transylvania. 1865, p. 44.

- ^ Wilhelm Schmidt: The ancestral castle of the Hunyad in Transylvania. 1865, p. 46.

- ^ Wilhelm Schmidt: The ancestral castle of the Hunyad in Transylvania. 1865, p. 56.

- ↑ Schulcz Ferencz (Hungarian), mek.niif.hu, accessed on March 16, 2009

- ^ University of Graz: Yearbook of the Art History Institute of the University of Graz. Akademische Druck und Verlagsanstalt, 1971, p. 23.

- ↑ Parlamentul Romaniei Camera Deputatilor (rum.) Accessed on March 26, 2009 (PDF; 4.8 MB)

- ↑ Cuibul de vulturi al Corvinilor ( Memento of December 3, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) (evz.ro, accessed on March 6, 2009)

- ^ Wilhelm Schmidt: The ancestral castle of the Hunyad in Transylvania. 1865, p. 45.

- ^ Wilhelm Schmidt: The ancestral castle of the Hunyad in Transylvania. 1865, p. 44.

- ↑ castelulcorvinilor.ro - documents, accessed on March 18, 2009 ( Memento of July 12, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ ( page no longer available , search in web archives )

- ^ Announcements of the anthropological society in Vienna. F. Berger, 1935, p. 76.

- ^ Wilhelm Schmidt: The ancestral castle of the Hunyad in Transylvania. 1865, p. 32.

- ↑ Carneycastle.com, accessed 7 March 2009

- ↑ a b Noutăți , accessed on March 26, 2009 (Romanian).

- ↑ castelulcorvinilor.ro - Museum, accessed on March 2, 2009 ( Memento from June 17, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ castelulcorvinilor.ro, accessed on March 6, 2009 ( Memento from July 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ castelulcorvinilor.ro, accessed on March 1, 2009 ( Memento from January 24, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Prosieben.de, accessed on March 1, 2009

- ↑ MYVideo - Don't waste your time, accessed July 3, 2009