Signature (art)

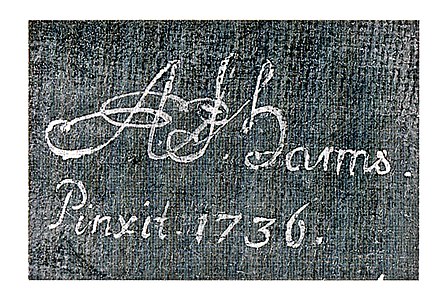

The signature is the signature of the name or the artist's mark and thus the copyright of an artist on his work. The signature is set up after the work is completed. They are written in full, reduced or ligated . A ligated signature is intertwined (also called a monogram ) or is formed as a pictorial monogram using signs and symbols. The signature is sometimes supplemented by a year or with explanatory additions such as pinxit (“he painted it”) or fecit (“he made it”).

Monogram, picture monogram, "speaking monogram"

- monogram

- is an artist's mark that is usually composed of the first letters of the artist's name who created the work of art.

- Image monograms

- are found relatively rarely on paintings. For the picture monogram, the artists used pictures, signs and symbols. Perhaps the best-known example of a pictorial monogram is the winged snake with a ring in its mouth and a crown on its head with Lukas Cranach the Elder. Ä. and his son "signed" her pictures. In the course of their artistic life, artists not only changed their signatures or monograms, but also their picture monograms, so that in the case of Lukas Cranach the Elder, for example. Ä. a rough chronological classification of his paintings is possible with the help of the picture monogram.

- Talking or talking monograms

- In art history, such signatures are called in which things are shown that either have the same name as the artist or can be derived from his name. The Flemish master Paul Bril (1554–1626) signed with glasses, the main master of the Ferrari school Dosso Dossi (around 1489–1542) signed with a bone ( osso ).

Forgery and authenticity

A large part, perhaps even the largest part, of the paintings that still exist were not signed by the artists or have no recognizable monogram or signature. A signed picture is easier to identify and promises greater profit in the market. For this reason, attempts were made at all times to upgrade unsigned paintings by adding a forged signature to them.

Real signatures age with the work of art and have the same signs of age. There are cracks in age ( craquelure ) not only in the paint layer of a painting, but also in the lines of the signature. A signature that was later placed on the painting is on the original craquelé and can therefore be recognized at a higher magnification than it was added later. Proof is more difficult if a painting has no or only very slight changes in age or a forged signature has aged centuries together with the painting. In most cases, only a comparative, graphological analysis is possible, in which the signature in question can be compared with secured original signatures of the artist.

Some signatures are difficult to read and photographically documented. Some are even only found with the help of a scientific painting examination because they are under heavily craquelured or browned varnishes or glazes. With the help of two methods, photography with double polarized light or with the help of infrared photography, it is often possible to make such signatures visible and documentable again.

history

Works of art were already signed in ancient times (since the 5th century BC), for example in Greek vase paintings. In the early Middle Ages the signature lost its importance because the artist anonymously stepped back behind his work of art. A few signatures can still be found on the decorative frame.

In the late period, the signature regains a certain meaning. But only the awakening of personality awareness among artists during the Renaissance increased the use of the signature to protect intellectual property . According to the modern image of man, the artist became a self-confident creator. With the development of a competitive art market at the latest , identification of the identity became a decisive evaluation factor.

Unsigned works of art

Unsigned works of art like in the Middle Ages are attempted in art history with the help of attribution, i.e. H. with the help of style criticism to assign an artist, an art era, an art landscape or a school. The style criticism assumes that every period is shaped by characteristic artistic conceptions. The individual artist is more or less subject to these and he gives expression to them with his artistic means. The time style influences the painting technique as well as the selection of motifs, formal elements and the way in which they are combined into a work of art. So in order to assign an unsigned work of art, the art historian has to record all of these features, order them. He has to recognize the features that are characteristic of a certain time, an art landscape, a school or a certain artist.

- Formations of signatures

Joseph Beuys

name written outAbbreviated picture signature of Karl Bobie's

first namePablo Picasso

only last nameSignature of Albrecht Dürer's

woodcut (as a monogram )The Cranach family of painters,

winged serpent with a ring in its mouthWolf Vostell's signature

with an indicated root sign

Name and monogram in the fine arts

It is best to use the artist's handwritten name for the signature to authenticate the authorship and to classify the work in a specific artistic curriculum vitae. What dating can still be helpful for. The question of the “if” of a signature continues to shift to the “how”. How a lettering is inserted into the image design or, if necessary, banished to the back as annoying. In the case of graphic reproductions, the signature in the template or printing form already allows the assignment (“signed in the stone”). Nevertheless, with modern graphics with a limited edition, the handwritten pencil signature of each individual sheet by the artist, usually in connection with a consecutive numbering of the copies (such as "36/100") has almost become the rule. It should guarantee the quality as the original graphic and the numerical limitation - although this is not always beyond doubt, as is the case with Salvador Dali . With other big names of classical modernism ( Pablo Picasso , Georges Braque , later Andy Warhol ) there are also individually unsigned prints in large numbers, sometimes from the same edition or based on the same template as signed copies, and then “ ceteris paribus ”in addition to the number of copies, the handwritten signature as an important value-creating factor. The derived nimbus of a highly personal marking may play a role here.

The monogramming, typically as a combination of two or three initial letters, may be understood as an alternative to naming, which identifies the author in a less intrusive way. It is an expression of modest stepping back behind the work, but at the same time also flirting with one's own fame, which can be recognized in the abbreviation. In fact, the monogram has been in the service of a modern-looking marketing strategy for a long time, at least with Albrecht Dürer , which turned the monogram into a logo or a brand . It shaped a corporate identity in the early manual workshop productions . A special and memorable graphic or calligraphic design is typical - such as the interlacing of the two letters in Albrecht Dürer's work. This execution experienced its climax under the influence of Art Nouveau , for example with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec or (with full name) with Egon Schiele . A certain degree of recognition of the artist is a prerequisite for the purposes of monogramming (the logo strives for recognition and at the same time assumes it). The considerable number of monograms documented in Goldstein's dictionary of monograms shows that some artists may have overestimated their potential for them. The contemporary often puzzles which real person is hidden behind the artist's monogram of his favorite picture.

Additional abbreviations

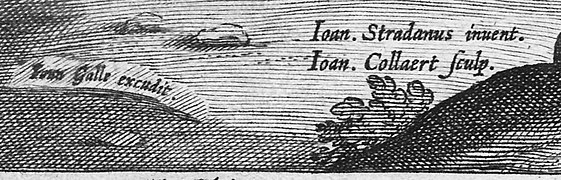

- Up until the 19th century, the name was often used on works of modern visual arts with the addition “ f. "Or" fec. “( Latin fecit with the meaning“ […] has made it ”added, on paintings often with a“ p. ”,“ Pinx. ”Or“ pinxit ”, has painted it '). In the case of reproductions, e.g. as a copper engraving of a painting, this can be used to describe the template.

- In the case of printmaking , a handwritten signature of the artist can be placed on each individual sheet or he has signed “in the plate”, i.e. a signature that is printed with the print is reversed, engraved or etched into the printing block. From the early modern period up to the 19th century, these printed signatures had the suffix “ sc. ” Or “ sculp. ” As an alternative to the “fecit” mentioned . "(Lat. Sculpsit ," [...] it stung ") or" gr. P. “( Fr. Gravé par , 'engraved by'). Must be distinguished from the citation of the designer or artist who created the sketch (is " inv. " For lat. Invenit , it has invented ', also called " del. " Or " delin. For" delineavit , it has drawn "or" pinx . ”For pinxit 'created the painting reproduced in the graphic').

- The lithographic printer or the lithographic company is marked with “ lith. "(" [...] lithographed it ") and the wood engraver who engraved the stick with" xyl. “(For xylographed, so 'made the wood engraving'). The " exc. “( Excudit 'has published') refers to the printer of the paper who is the publisher. This naming of those involved in the production process on graphical sheets from the 16th to the 19th century is called "address". If arranged in a line below the edge of the picture, the artist is usually on the left and the publisher on the right.

- Often (or only) the name of the foundryman or the casting workshop appears on bronze castings , the name of the medalist (die cutter) and possibly the mint on medals . If a bust was used as a template for the engraving of the medal, the signature of the sculptor can also be indicated on the medal .

- XA or XA ("Xylographische Anstalt") was mainly used in the 19th century to supplement the signatures on wood engravings , for example by Johann Gottfried Flegel , Richard Brend'amour and Eduard Hallberger .

List of Latin terms

The following are common Latin terms and abbreviations listed on prints.

reproduced in the name of the painter or draftsman, for example in a copper engraving |

|

|---|---|

| p ., pinx ., pinxit | painted [it] |

| del ., delin ., delineavit | has drawn |

| inv ., inven ., invenit | has designed |

| comp ., composuit | did |

| fig ., figuravit , effigiavit | has shown |

| by the name of the engraver | |

| cael ., caelavit | has engraved |

| inc ., incidit | has cut |

| by the name of the engraver or eraser | |

| sc ., sculp ., ( aere ) sculpsit , exculpsit | has engraved (in copper) |

| ( aere ) exarat | grub (in copper) |

| f ., fec ., fecit | did [it] |

| by the name of the eraser | |

| f ( ecit ) aqua ( fortis ) | made with (strong) water |

| by the name of the printer | |

| imp ., impressit | has printed |

| in the name of the publisher (in the sense of a printer or publisher) |

|

| exc ., excudit | has published |

| div ., divulgavit | has spread |

| formis | with printing forms from |

| sumptibus | at the expense of |

| in photographic techniques | |

| ph. , ph.sc. , photosculpsit | who has edited a template z. B. a heliogravure |

- Examples of signatures

Henricus F.ab Langren Sculpsit - signature of the engraver Henricus Florentius van Langren , from Deliniantur in hac tabula ... , Amsterdam, 1596

G. Eberlein fec. 1903 - Engraving by the sculptor Gustav Eberlein on the Wagner monument in Berlin

Related terms

- In the applied arts of the pre-industrial era, the printed, punched, embossed or stamped manufacturer's marks are usually not referred to as “signatures”, although they often have this function. A signature that is manually painted on ceramic, engraved in metal or cut into artificial glass is correctly named that way.

- Chinese seal - a name stamp in the Chinese art tradition

- Printer brand

- Coin and medal signature

- Stonemason's mark

Legal

- Falsification of an artist's signature is a criminal offense according to § 107 UrhG .

- Forgery of works of art ( art forgery ) is not an independent offense in Germany, but is punished according to § 263 StGB ( fraud ) and § 267 StGB ( forgery of documents ).

literature

-

Georg Kaspar Nagler : The monogramists and those known and unknown artists of all schools who use a figurative sign, the initials of the name, the abbreviation of the same to designate their works , & c. have served. Taking into account letterpress marks , the stamp of art collectors , the stamp of the old gold and silversmiths, the majolica factories , porcelain manufacturers, etc. News about painters , draftsmen , sculptors , architects , engravers , shape cutters , letter painters , lithographers , stamp cutters , enamellers , goldsmiths, Niello , metal and ivory workers, engravers , armourers, etc. With the rapid indexes of the works of anonymous masters , whose marks are given, and the reference to the products of well-known artists labeled with monograms or initials ... also supplement ... the New general artist lexicons, and supplement to the well-known works by A. Bartsch, Robert-Dumesnil, C. le Blanc, F. Brulliot , J. Heller, etc.

-

First volume , Munich: Georg Franz, 1858

- also available as a reprint from 1991

-

First volume , Munich: Georg Franz, 1858

- Joseph Heller: Monogram lexicon, containing the known, dubious and unknown CHARACTERS, as well as the abbreviations of the names of the draftsmen, painters, form cutters, engravers, lithographers etc. with short messages about the same ...

-

Second volume , Bamberg by JS Sickmüller, 1831

- Unchanged reprint of the edition: Niederwalluf near Wiesbaden: M. Sendet, 1971, ISBN 3-500-23590-5 .

-

Second volume , Bamberg by JS Sickmüller, 1831

- Brockhaus art. Artists, epochs, technical terms . 3rd, update u. revised Edition. Verlag F. A. Brockhaus, Mannheim 2006, ISBN 3-7653-2773-5 , pp. 844-845.

- Felix Philipp Ingold : On the signature of the work. In: ders .: On behalf of the author. Works for art and literature. Wilhelm Fink, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-7705-3984-2 , pp. 299-374.

- Ernst Rebel: Printmaking. History, technical terms . Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-15-018237-9 , pp. 247-249.

- Fritz Goldstein, Ruth Kähler: Monogram Lexicon. International directory of monograms by visual artists since 1850. Volume 1, Verlag de Gruyter, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-11-014453-0 .

- Paul Pfisterer: Monogram Lexicon. International directory of monograms by visual artists of the 19th and 20th centuries. Volume 2, Verlag de Gruyter, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-11-014300-3 .

- Joachim Heusinger von Waldegg: Signatures of Modernity. Ernest Rathenau-Verlag, Karlsruhe 2015, ISBN 978-3-946476-00-9 .

Special:

- Franz Bornschlegel: Style Pluralism or Unity? The writings in the South German sculpture workshops of the early Renaissance. In: Epigraphik 2000. Ninth symposium for medieval and modern epigraphy. Klosterneuburg, 2000, ed. Gertrud Mras, Renate Kohn: Research on the history of the Middle Ages 10, Vienna 2006, pp. 39–63.

- MJ Libmann: The artist's signature in the 15th and 16th centuries as an object of sociological investigation. In: Peter H. Feist (Ed.): Lucas Cranach, Artists and Society . Cranach Committee of the German Democratic Republic, Wittenberg 1973.

Web links

- Ad Stijnmann: Explanation of labels on graphic sheets . At: Virtual Kupferstichkabinett (PDF, 209 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Knut Nicolaus: Signatures - real or forged . In: Art & Antiques . tape III , 1988.

- ↑ Joachim Heusinger von Waldegg: Signatures of Modernity . 2015, p. 31, 321 .

- ^ Franz Goldstein, Ruth Kähler: Monogram Lexicon. International directory of monograms by visual artists since 1850 . tape 1 , 1999.

- ↑ z. B. Entry Pinxit. In: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon . 6th edition. tape 15 .. Leipzig 1908, p. 894 ( zeno.org ).

- ↑ z. B. Entry Del. [2]. In: Herders Conversations-Lexikon . tape 4 .. Freiburg im Breisgau 1854, p. 808 ( zeno.org ).

- ^ Fons van der Linden: DuMont's handbook of graphic techniques: manual and machine printing processes; Letterpress, gravure, planographic printing, screen printing; Reproduction techniques, multi-color printing . DuMont, Cologne 1983, ISBN 3-7701-1237-7 , pp. 103 f .

- ^ Antony Griffiths: Prints and printmaking; To introd. to the history and techniques . British Museum Publ., London 1980, ISBN 0-7141-0770-0 , pp. 124 .

- ↑ Deliniantur in hac tabula… , picture on Wikimedia Commons, excerpt

- ↑ Information from the German National Library