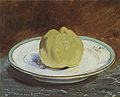

Asparagus bunch

Édouard Manet , 1880

46 × 55 cm

oil on canvas

Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud , Cologne

The asparagus bundle , also a bundle of asparagus , asparagus bunch , asparagus or asparagus still life ( French Une botte d'asperges or Asperges ), is a still life by Édouard Manet, painted in oil on canvas in 1880 . It has a height of 46 cm and a width of 55 cm. It shows a bunch of asparagus on green foliage and a white surface against a dark background. The picture, which is reminiscent of Dutch Baroque painting in terms of motifs , belongs to Manet's late work with its impressionistic style of painting. The history of reception is unusually extensive and varied for a still life. Manet's asparagus bundle served the painter Carl Schuch as a model for his own works, it flowed into the literary work of the novelist Marcel Proust and the conceptual artist Hans Haacke used the provenance of the painting to show the path of an Impressionist picture from France through various Jewish collections before it was acquired in 1968 with donations from German companies for the collection of the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Cologne .

Image description

Manet's asparagus bundle shows a motif based on traditional still life painting . In the center of the picture lies a bundle of white asparagus spears in the bright light. The view goes from the side to the asparagus bundle, the purple tips of which are aligned to the right edge of the picture. It is held together by two thin willow rods that were used to transport the vegetables. The asparagus bunch lies on a base of green leaves that extend from the left side to the lower right corner of the picture. Manet's biographer Théodore Duret speaks of a “lit d'herbes vertes” (bed of green leaves) . For the art historian Mikael Wivel , Manet presents the asparagus the way a greengrocer shows his goods. A bluish-white background can be seen at the bottom left and in the middle of the right edge of the picture, which could be a tablecloth or a light marble slab. The signature “Manet” can be found on the lower left on this light background. The upper half of the picture is covered by a black and brown background, in which “the colors are velvety interwoven”, as the author Gotthard Jedlicka states.

In this composition, the green leaves and the purple asparagus tips have the difficult task of separating the asparagus stalks from the ground, both of which have a similar color. Gotthard Jedlicka sees a connection to the colors of the background in the dark willow branches. For him, there is also a first impression in which the asparagus spears appear yellow and the tips appear purple. On closer inspection, however, they are "painted with an indescribable wealth of color tones". In the asparagus stalks, Jedlicka sees further color nuances in yellow, such as blue, white, rosy and violet tones, and in the tips he recognizes red, blue, green, yellow and other colors, with each tip being individually painted. For Jedlicka, Manet's brushstroke ranges from “wide and pastose application to the finest drawing in lines and dots”. The museum director Gert von der Osten emphasizes that Manet's still lifes were “painted quite openly impressionistically with ingenious accuracy”.

Manet's style of painting in this picture was examined in detail by employees of the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud in Cologne in 2008 on the occasion of the exhibition Impressionism: How light came onto the canvas . When looking at the work in transmitted light, in which the painting is illuminated from behind, it could be proven that Manet applied the brown color of the background to the gray-primed canvas in a thin, " old-master " manner . He worked with a flat brush and left out the area of the asparagus stalks. When looking at the painting with the help of a microscope, the painting style in the area of the asparagus was also analyzed. Here Manet worked with a narrow brush and placed the lines next to one another and crossed them. In contrast to traditional painting, he did not mix the colors carefully on the palette, but first directly on the canvas. The impression of the fleeting style of painting is reinforced by the sometimes impasto application of the paint. The “wet on wet painted colors” are a sign that Manet probably created the painting within “a single working session”.

Manet's second asparagus picture

Manet's bundle of asparagus is closely linked to another painting by the artist, the picture The Asparagus in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris , on which a single asparagus stick can be seen. There is an anecdotal story about the creation of the two pictures. Afterwards the art collector Charles Ephrussi saw the painting Bundle of Asparagus in Manet's studio in 1880 and arranged with the painter to buy the picture for 800 francs , but generously sent him 1000 francs. Manet then painted the small-format picture The Asparagus and sent it to Ephrussi. He added the note to the picture at “Il en manquait une à votre botte” (“There is still one missing in your bundle”).

The two pictures differ not only in terms of motif and size, but also in terms of color and design. While the asparagus bundle appears in the old masters chiaroscuro, Manet chose a light color palette typical of Impressionism for the individual asparagus stalks. Ephrussi was the last to own both Manet's asparagus pictures. During his lifetime he already sold the bundle of asparagus to the art trade, and after his death in 1905 the Bernheim-Jeune art dealer bought the asparagus stick . After that, the two pictures were rarely exhibited together. These include the Manet exhibitions in Charlottenlund in 1989 and in Madrid in 2003/2004. Most recently, both pictures were combined in exhibitions in 2017–2018 in Washington, DC and in 2019 in Chicago.

role models

A direct model for Manet's asparagus bundle is not known. However, various authors see a motivic relationship to Dutch baroque still life painting. For example, there are asparagus tied together in the elaborate still life compositions by Cornelis de Vos , Frans Snyders or Jan van Kessel the Elder . The closest match of the motif - a single bunch of asparagus on a table against a dark background - can be found in several pictures by the Dutch painter Adriaen Coorte . Manet knew some museums in the Netherlands from occasional trips to his wife Suzanne's homeland , but he had probably never seen any pictures by Coorte. On the other hand, he certainly knew the still lifes of his contemporaries Philippe Rousseau and François Bonvin , who repeatedly showed bundles of asparagus in their paintings. He was also familiar with the motif of a bundle of asparagus from the immediate vicinity. The Manet family owned land in Gennevilliers , which, like neighboring Argenteuil, was a well-known asparagus-growing area. Asparagus was therefore probably one of the dishes served in the Manet house and the painting Asparagus Bundle was probably created during the asparagus season in April or May 1880.

Manet's still life

In Manet's oeuvre there are still lifes in different work phases. His early still lifes from the 1860s show a clear relationship to images of baroque painting . These include the 1866 paintings The Salmon ( Shelburne Museum , Shelburne) and Still Life with Melon and Peaches ( National Gallery of Art , Washington, DC), which have complex arrangements of various objects. The art historian Emil Waldmann compared Manet's still lifes with the works of older artists and commented: “In his still life art , the most beautiful still life art there is, despite the Dutch, despite Chardin and Courbet , this incomparable ability to paint [...] celebrates the most incredible festivals , strangest kind. "

In contrast to Manet's early still lifes, his depictions of fruit and vegetables are in the last years of his life. Between 1880 and 1883 Manet repeatedly painted pictures in which a few identical objects or individual pieces became the subject. Still lifes like The Lemon ( Musée d'Orsay , Paris) or Apple on a plate (private collection) were created. For Mikael Wivel, Manet's late still lifes such as the Bundle of Asparagus and The Asparagus are not “natures mortes” (still life, literally dead nature ) in the traditional sense, but rather individual portraits of an object. Art historians therefore read Manet's still lifes less as vanitas pictures that symbolize transience ; in the case of asparagus bundles , such an assignment is entirely absent.

Provenance

Shortly after the painting was completed, it was bought by the banker and art collector Charles Ephrussi in 1880 , who paid 1000 francs for the picture (see Manet's second asparagus picture ). Ephrussi repeatedly loaned the picture to exhibitions: in 1884 for the Manet Memorial Exhibition at the Paris École des Beaux-Arts , in 1889 for the World Exhibition in Paris and in 1900 for the Exposition Centennale de l'Art Français as part of the Paris World Exhibition . Between 1900 and 1902 Ephrussi gave the still life to the Paris art dealer Alexandre Rosenberg . It has not been proven whether he sold it directly to him or initially gave it on commission. Various authors such as the Cologne museum director Gert von der Osten have assumed that the next owner was the Berlin legal scholar Carl Bernstein . Bernstein was a cousin of Ephrussi and had brought the first pictures of French Impressionism to Germany in 1882 and showed his collection in Berlin. However, Bernstein died in 1894 when the painting was still in Ephrussi's possession. Carl Bernstein is therefore leaving the previous owner.

The asparagus bundle came to Berlin in 1903 at the latest. The art dealer Paul Cassirer took over the picture and exhibited it in May 1903 at the VII Art Exhibition of the Berlin Secession . Its president was the Berlin painter Max Liebermann . He must have seen the picture in this exhibition and read the positive review of the picture in the magazine Kunst und Künstler . But he probably knew the picture earlier, as he was in Paris with Ephrussi. Liebermann finally acquired the painting on April 6, 1907 from Paul Cassirer for 24,300 Reichsmarks. As can be seen from the photographs, the picture found its place in the Liebermann Villa on Wannsee. Liebermann loaned the picture to the 1926 International Art Exhibition in Dresden and the 1932 Manet Exhibition in Paris. He remained the owner of the painting until his death in 1935. After the so-called " seizure of power " by the National Socialists in 1933 and the Reichstag fire that followed a few weeks later, Liebermann - whose house on Pariser Platz was within sight of the Reichstag - decided to take parts of his art collection abroad. Under the pretext of showing the pictures in exhibitions abroad, the art dealer Walter Feilchenfeldt , who was a friend of Liebermann, was able to persuade the director of the Kunsthaus Zürich , Wilhelm Wartmann , to take 14 pictures from the collection. These included Manet's bundle of asparagus , which was actually shown in the 1938 exhibition Honderd Jaar Franske Kunst in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam . In the same year, Liebermann's daughter Käthe managed to leave Germany together with her husband Kurt Riezler and their daughter Maria. They were able to take the pictures from the Liebermann Collection previously stored in Zurich with them to the United States. After the death of Liebermann's wife Martha , who committed suicide in 1943 before the planned deportation to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, the daughter Käthe, now living in New York City, inherited the asparagus still life. She died in 1952, her husband in 1955. The remaining art collection of Max Liebermann passed into the possession of her daughter Maria White, who lived in Northport . This loaned the picture from 1966–1967 for the Manet retrospective in Chicago and Philadelphia .

After Konrad Adenauer's death in 1967, the bank manager Hermann Josef Abs, in his capacity as chairman of the Wallraf-Richartz Board of Trustees, the friends' association of the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne , initiated a fundraising campaign to give the museum a painting in memory of the former mayor of Cologne and first Federal Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany. Numerous German companies, including banks, trading companies and industrial companies, took part in the fundraising campaign. Through the mediation of the art dealer Marianne Feilchenfeldt , Walter Feilchenfeldt's widow, Abs acquired Manet's asparagus still life from Maria White's possession for USD 1,360,000. In the same year, the painting entered the collection of the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum on permanent loan from the Board of Trustees. As the museum, as one of the few important art collections in the Federal Republic of Germany, did not yet have any work by Manet, the new addition closed an important gap. The picture of a French painter with the dedication in memory of Konrad Adenauer is at the same time symbolically linked to the work of the Chancellor for the Franco-German friendship .

reception

Carl Schuch

Manet's bundle of asparagus had an influence on other artists from an early age . In 1884 the painters Karl Hagemeister and Carl Schuch visited the Manet memorial exhibition in Paris at the École des Beaux-Arts , in which, among other things, the bundle of asparagus could be seen. Hagemeister later recalled how Manet's works had an effect on Schuch: "He studied the asparagus and Manet's roses [...] in detail and considered them to be a step forward against the ancients and Courbet." Schuch then repeated in his Paris years until 1892 a bundle of asparagus integrated into his still lifes, such as the paintings Apples on White; with basket, pewter jug and asparagus bundle from 1884/1885 ( Kaiser Wilhelm Museum , Krefeld) and lobster, tin can and asparagus bundle from 1884 ( Von der Heydt Museum , Wuppertal).

Marcel Proust

Charles Ephrussi, the first owner of Manet's asparagus bundle , had the writer Marcel Proust as a guest in his apartment in the spring of 1899 . Proust saw Manet's bundle of asparagus there and later used it as a suggestion for various passages in his novel In Search of Lost Time . In the volume In Swanns Welt, he describes asparagus stalks, “which looked as if they had been painted with ultramarine and pink and whose tips, dipped in violet and sky blue, one after the other - which still bore traces of the nourishing soil - had shades of iridescent colors that were not earthly Proust also took up the story of Ephrussi's acquisition of the asparagus picture and had his fictional characters discuss the value of an asparagus picture: “Swann actually had the forehead to advise us to buy the asparagus bundle. We even had the picture in the house for a few days. There was nothing more than that on it, a bunch of asparagus, just like the one we're swallowing, but I didn't swallow Mr Elstir's asparagus. He asked for three hundred francs for it. Three hundred francs for a bunch of asparagus! They are worth at most a Louis d'or ... "

German-speaking authors

When Manet's bundle of asparagus was shown in the exhibition at the Berlin Secession in 1903 , the art critic Emil Heilbut praised the painting in the magazine Kunst und Künstler : “Then follows a bunch of asparagus, which are brightly colored on green leaves, a work that is wonderfully, is just almost too beautiful. a sweet euphoria of the color, the perfection itself. ”Later, the asparagus bundle was in the possession of the painter Max Liebermann , who in 1916 declared in an article for the magazine Kunst und Künstler ,“ a bundle of asparagus [...] is enough for a masterpiece ”. In his Manet biography, published in 1912, Julius Meier-Graefe paid tribute to the work: “The asparagus at Liebermann's are much more than asparagus. The peculiarity of matter, which is not based on color alone but on reactions of our sense of touch and all sorts of other sensations, is not only reproduced here, but doubled. It is as if the entire sensual apparatus of our body is concentrated in the eyes ”. The Berlin museum director Hugo von Tschudi praised Manet's late work still lifes - whereby he also mentioned the asparagus bundle - and underlined that the painter of nature succeeded in unveiling “coloristic charms of previously unimagined delicacy”.

The art theorist August Endell studied Manet's bundle of asparagus in detail in 1908 . He saw in the picture a “wonderfully perfect technique” and certified the painter that he had discovered “that a bunch of asparagus, which until then had only been regarded as an edible object, is a small wonderland of the most delicate, wonderful colors, so beautiful and so charming as the fragrant flower, as the most beautiful woman ”. On the basis of Manet's bundle of asparagus, Endell went on to explain the difference between the “object of our thought” and the “perceptual image”. He made a distinction: "Manet had only seen the asparagus with the air above it and the shadow, the others had only seen edible asparagus without color, without shadow, without air, because none of that could be eaten." Seeing work more than edible asparagus, be it, according to Endell, "a revelation, the beginning of a new, richer life".

For the art historian Gotthard Jedlicka, Manet's asparagus bundle is one of the “gems” that “claim and control an entire wall on their own”. Manet has succeeded in reproducing "a whole world in an indescribable abundance of drawings and colors" "with the simple motif of a bundle of asparagus on a kitchen table".

Hans Haackes Manet Project '74

For the 150th anniversary of the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum , the exhibition Projekt '74 took place in Cologne . In the summer of 1974, in addition to the Wallraf-Richartz Museum, other cultural institutions such as the Kunsthalle Köln and the Kölnischer Kunstverein presented “Art in the early 1970s” under the motto “Art remains art ”. The artist Hans Haacke , who then submitted his Manet project '74 , was also invited to this exhibition . In a room installation he wanted to present Manet's painting Bundles of Asparagus on an easel and on ten panels on the walls to depict the social and economic situations of the people who had possessed the picture since its creation. Although the project had prominent advocates in Evelyn Weiss , then curator for modern art at the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Manfred Schneckenburger , director of the Kunsthalle, and Wulf Herzogenrath , director of the Kunstverein, it was made by Gert von der Osten, the general director of the museums the city of Cologne, declined without knowing the details of the project. The Manet project '74 was shown instead in the Cologne gallery by Paul Maenz . Since Manet's original picture was not available there, Haacke made do with a color reproduction in original size.

Haacke had determined the provenance of the asparagus bundle and found out that, according to Manet, all other owners of the picture and all art dealers who were ever involved in the sale of the picture were Jews. He presented the résumés of the individual previous owners, including those of Max and Martha Liebermann. Another panel was dedicated to Hermann Josef Abs . The chairman of the Wallraf-Richartz board of trustees and long-time spokesman for the board of directors of Deutsche Bank initiated the purchase of the painting for the museum. In his résumé, Haacke not only listed Abs's role in the Federal Republic, but also his numerous functions during the National Socialist era, during which he played an inglorious role "in the" Aryanization "of Jewish assets". The journalist Annika Karpowski commented: "The supposedly generous patron, the banker Hermann Joseph Abs, turned out to be the beneficiary of the expropriation of Jewish assets." The non-approval of Haackes Manet project '74 at the official exhibition of the city of Cologne solved many Protests from other artists, including Daniel Buren and Sol LeWitt . With his work, Haacke anticipated later discussions about looted art and provenance research.

literature

- Brigitte Buberl (Ed.): Cézanne, Manet, Schuch; three ways to autonomous art . Exhibition catalog Museum for Art and Cultural History of the City of Dortmund, Hirmer, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-7774-8640-X .

- Günter Busch (Ed.): Max Liebermann, Vision of Reality, selected writings and speeches . Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-596-11686-4 .

- Françoise Cachin , Charles S. Moffett and Juliet Wilson-Bareau : Manet: 1832–1883 . Exhibition catalog, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, German edition: Frölich and Kaufmann, Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-88725-092-3 .

- Théodore Duret : Histoire d'Édouard Manet et de son oeuvre: avec un catalog des peintures et des pastels . H. Floury, Paris 1902.

- August Endell : The Beauty of the Big City . Strecker & Schröder, Stuttgart 1908.

- TA Gronberg: Manet, a retrospective . Levin, New York 1989, ISBN 0-88363-173-3 .

- Stéphane Guégan: Manet, inventeur du moderne . Exhibition catalog Paris, Gallimard, Paris 2011, ISBN 978-2-07-013323-9 .

- Karl Hagemeister : Karl Schuch, his life and his works . Cassirer, Berlin 1913.

- Anne Coffin Hanson : Edouard Manet . Exhibition catalog Philadelphia Museum of Art and The Art Institute of Chicago, Falcon Press, Philadelphia 1966.

- Emil Heilbut : Art and Artist . Bruno Cassirer, Berlin 1903.

- Paul Jamot: Manet . Exhibition catalog, Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris 1932.

- Gotthard Jedlicka : Manet . Rentsch, Erlenbach 1941.

- Luzius Keller: Marcel Proust Encyclopedia . Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-455-09561-6 .

- Peter Lünzner: Asparagus with Manet and Proust . Lünzner, Hanover 2001.

- George Mauner: Manet, the still-life paintings . Exhibition catalog Paris, Baltimore 2000–2001. Abrams, New York 2000, ISBN 0-8109-4391-3 .

- Galerie Matthiessen (ed.): Exhibition Edouard Manet, 1832–1883, paintings, pastels, watercolors, drawings . Matthiessen Gallery, Berlin 1928.

- Manuela B. Mena Marqués: Manet en el Prado . Exhibition catalog, Madrid 2003, ISBN 84-8480-053-9 .

- Julius Meier-Graefe : Edouard Manet. Piper, Munich 1912.

- George Moore : Modern painting . W. Scott, London 1898.

- Tobias G. Natter , Julius H. Schoeps (Eds.): Max Liebermann and the French Impressionists . Exhibition catalog Jewish Museum Vienna, DuMont, Cologne 1997, ISBN 3-7701-4293-4 .

- Wolfram Nitsch: Marcel Proust and the arts . Contributions to the Proust symposium and the arts of the Marcel Proust Society in Cologne in November 2002, Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-458-17207-6 .

- Sandra Orienti: Edouard Manet . Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main 1981, ISBN 3-548-36050-5 .

- Gert von der Osten : Manet, dedicated by the Wallraf-Richartz Board of Trustees to the willing donors to acquire Edouard Manet's still life for the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne . Combination of two articles from the Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch Volume XXXI 1969 and Volume XXXIII 1971, Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne.

- Marcel Proust : In search of lost time . Translation by Eva Rechel-Mertens, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1979, ISBN 3-518-03949-0 .

- Eliza E. Rathbone (Ed.): Renoir and friends: Luncheon of the boating party . Exhibition catalog The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC 2017, ISBN 978-1-911282-00-6

- Iris Schäfer, Caroline von Saint-George, Katja Lewerentz: Impressionism, How light came onto the canvas . Exhibition catalog Cologne and Florence, Skira, Milan 2008, ISBN 978-88-6130-611-0 .

- Allan Scott, Emily A. Beeny, Gloria Lynn Groom (Eds.): Manet and modern beauty: the artist's last years . Exhibition catalog Art Institute of Chicago and J. Paul Getty Museum, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 2019, ISBN 978-1-60606-604-1 .

- Hugo von Tschudi : Edouard Manet . Bruno Cassirer, Berlin 1913.

- Mikael Wivel : Manet. Exhibition catalog Charlottenlund, Copenhagen 1989, ISBN 87-88692-04-3 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ The following titles can be found in the literature: Bundles of asparagus in Gert von der Osten: Manet , p. 7 and G. Tobias Natter, Julius H. Schoeps: Max Liebermann and the French Impressionists , p. 216; A bunch of asparagus in Sandra Orienti: Edouard Manet , p. 52; Bundle of asparagus in Françoise Cachin, Charles S. Moffett, Juliet Wilson-Bareau: Manet , p. 451; Asparagus in Emil Heilbut: Art and Artists , p. 292, Asparagus Still Life in Iris Schäfer, Caroline von Saint-George, Katja Lewerentz: Impressionism , p. 126.

- ↑ Une botte d'asperges is given as a French title by Natter / Schoeps, see G. Tobias Natter, Julius H. Schoeps: Max Liebermann und die Französisch Impressionisten , p. 216; Asperges is the title in the Manet exhibition in Paris in 1932, see Paul Jamot: Manet , p. 60.

- ↑ a b c Gert von der Osten: Manet , p. 7.

- ↑ Théodore Duret: Histoire d'Édouard Manet et de son oeuvre , p. 261.

- ^ "The bunch lies there just as the greengrocer would have displayed it on his counter" in Mikael Wivel: Manet , p. 140.

- ↑ Gotthard Jedlicka speaks of a "white, bluish shimmering oilcloth" and of a "tablecloth" in Gotthard Jedlicka: Manet , p. 199. Thereafter he describes the underground as a "tablecloth" or generally as a "kitchen table" in Gotthard Jedlicka: Manet , P. 200.

- ↑ Juliet Wilson-Bareau has referred to a “marble surface that appears again and again in his late still lifes”, see Juliet Wilson-Bareau: Manet: Immediately paint what one sees in Brigitte Buberl: Cézanne, Manet, Schuch; Three Paths to Autonomous Art , p. 122. Such a table can be seen, for example, in the paintings Roses and Tulips in a Vase , Roses in a Glass Vase and The Bouquet of Lilacs . From Manet's visitor, George Moore, it is recorded that "a marble table on iron supports, such as one sees in cafes" (a marble table with iron feet, like you can see it in cafes) was in his studio, see George Moore : Modern painting , p. 31.

- ↑ a b c d e f Gotthard Jedlicka: Manet , p. 200.

- ↑ In relation to the painting with the individual asparagus, Manuela B. Mena Marqués pointed out how difficult it is to paint the asparagus when the background is the same: “Asparagus is perhaps the most difficult of all the studies he produced during those months; the yellowish white vegetable lies on a table of the same color ". Catalog text in English from Manuela B. Mena Marqués: Manet en el Prado , p. 485.

- ↑ Iris Schäfer, Caroline von Saint-George, Katja Lewerentz: Impressionism: How light came onto the canvas , p. 127.

- ↑ a b c Gert von der Osten: Manet , p. 9.

- ↑ a b Mikael Wivel: Manet , p. 140.

- ↑ Manuela B. Mena Marqués: Manet en el Prado , p. 323.

- ↑ Eliza E. Rathbone: Renoir and friends, Luncheon of the boating party , pp. 95 and 133.

- ↑ The Cologne asparagus picture was only awarded for the exhibition in Chicago. See Allan Scott, Emily A. Beeny, Gloria Lynn Groom: Manet and modern beauty: the artist's last years , p. 291.

- ↑ Mena Marqués reminds the picture of baroque painting, see Manuela B. Mena Marqués: Manet en el Prado , p. 485; Françoise Cachin writes that the bundle of asparagus is “a bit like the Dutch still life of the seventeenth century”, see Françoise Cachin, Charles S. Moffett, Juliet Wilson-Bareau: Manet , p. 451.

- ↑ Adriaen Coorte's painting Asparagus Bundle did not enter the collection of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam until 1903, that is, 20 years after Manet's death. George Mauner notes: "... the one by S. Adrian Coorte in the seventeeth century, which he had, in fact, never actually seen ..." George Mauner: Manet, the still-life paintings , p. 48; Gert van der Ostern keeps the question open and writes about Coortes still life: "... if Manet should have known the earlier work ...", Gert von der Osten: Manet , p. 11.

- ↑ George Mauner refers to pictures of asparagus by Manet's contemporaries. In George Mauner: Manet , p. 48.

- ↑ Mena Marqués suspects the period of origin to be April or May, see Manuela B. Mena Marqués: Manet en el Prado , p. 485

- ^ Galerie Matthiessen: Exhibition Edouard Manet, 1832–1883, paintings, pastels, watercolors, drawings , p. 12.

- ↑ TA Gronberg: Manet, a retrospective , S. 346th

- ↑ Gert von der Osten: Manet , p. 9. In the exhibition catalog Philadelphia, Chicago 1966–1967, “Bernstein, Paris” is named as one of the previous owners of the picture. See Anne Coffin Hanson: Édouard Manet . P. 192. In the exhibition on Manet's still lifes in Paris and Baltimore 2000–2001, “Bernstein Berlin 1907” is noted as the previous owner. See George Mauner: Manet, the still-life paintings , p. 174.

- ↑ Natter, Schoeps: Max Liebermann and the French Impressionists , p. 237.

- ↑ TA Gronberg: Manet, a retrospective , S. 347th

- ↑ Such a photo with Max Liebermann seated in front of the Manet pictures Madame Manet in the garden in Bellevue and bundles of asparagus on the wall is reproduced in Natter, Schoeps: Max Liebermann and the French Impressionists , p. 231.

- ^ A b Anne Coffin Hanson: Édouard Manet , p. 192.

- ↑ a b Natter, Schoeps: Max Liebermann and the French Impressionists , p. 241.

- ^ With a letter of May 2, 1933 to Director Dr. Wartmann lists Walter Feilchenfeldt 14 pictures from the Liebermann collection that should be handed over to the Kunsthaus Zürich for safekeeping. In addition to works by Cézanne , Degas , Daumier , Renoir and Monet , this list includes six works by Manet. Position 1 on this list is labeled Manet, asparagus . The list is reprinted in Natter, Schoeps: Max Liebermann and the French Impressionists , p. 239.

- ↑ a b c T. A. Gronberg: Manet, a retrospective , p. 348.

- ↑ TA Gronberg: Manet, a retrospective , S. 363rd

- ↑ The Wallraf-Richartz-Museum acquired a portrait of Antonin Proust von Manet through Hildebrand Gurlitt in 1943 for 3,300,000 francs (165,000 Reichsmarks), but had to return the picture to France after 1945. The painting is now in the Musée Fabre in Montpellier . See Stéphane Guégan: Manet, inventeur du moderne , p. 283 and entry on the portrait of Antonin Proust at www.culture.gouv.fr .

- ^ Karl Hagemeister: Karl Schuch, his life and his works , p. 152.

- ↑ Several authors have written about Manet's asparagus bundles as a template for certain passages in Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time , for example Luzius Keller in Proust and the art collectors in Wolfram Nitsch: Marcel Proust und die Künste , p. 305.

- ↑ Marcel Proust: In Search of Lost Time , Volume 1 In Swanns Welt , p. 162.

- ↑ Marcel Proust: In Search of Lost Time , Volume 5 Die Welt der Guermantes , p. 1911.

- ^ Emil Heilbut: The Exhibition of the Berlin Secession in Art and Artists, p. 309.

- ↑ Max Liebermann published the article Appearance and Fantasy in the magazine Kunst und Künstler in 1916, in which he paid tribute to Manet's asparagus bundles . See Günter Busch: Max Liebermann, Vision of Reality, selected writings and speeches , p. 50.

- ^ Julius Meier-Graefe: Edouard Manet , p. 288.

- ↑ Hugo von Tschudi: Edouard Manet , pp. 50–51.

- ↑ August Endell: The Beauty of the Big City , pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Gotthard Jedlicka: Manet , p. 199.

- ^ Jürgen Hohmeyer: Art on the dump . Article in Der Spiegel from July 15, 1974

- ↑ TA Gronberg: Manet, a retrospective , S. 343rd

- ↑ Niklas Maak: Art critical? . Article in the FAZ of December 22, 2006.

- ↑ Annika Karpowski: Happy Birthday, Hans Haacke! , Article on http://www.artnet.de/ from August 12, 2011

- ↑ TA Gronberg: Manet, a retrospective , S. 345th