Hildebrand Gurlitt

Hildebrand Gurlitt (born September 15, 1895 in Dresden , † November 9, 1956 in Oberhausen ) was a German art historian and art dealer . From 1925 to 1930 he was director of the König-Albert-Museum in Zwickau and from 1931 to 1933 director of the art association in Hamburg . During the National Socialist era he worked as an art dealer. On the one hand, he was commissioned to sell the so-called “ degenerate art ” (defamed modern and avant-garde art ) confiscated from German museums abroad. On the other hand, after the beginning of the Second World War , Gurlitt was one of the main buyers for the Hitler Museum in Linz in the National Socialist art theft, mainly in France. From 1948 he was head of the art association for the Rhineland and Westphalia .

Life

family

Hildebrand Gurlitt came from Dresden. His father was the art historian Cornelius Gurlitt , his grandfather the landscape painter Louis Gurlitt . His grandmother Elisabeth Gurlitt (nee Lewald) was a sister of the writer Fanny Lewald , she came from a Jewish family. One of his brothers was the musicologist Wilibald Gurlitt , Hildebrand Gurlitt's cousins were the art dealer Wolfgang Gurlitt and the composer Manfred Gurlitt .

Hildebrand Gurlitt married the dancer Helene ("Lena") Hanke (1895–1968) in 1923, called "Bambula" by her classmates like Yvonne Georgi , one of Mary Wigman's first students . With her he had the son Cornelius (1932–2014) and a daughter Nicoline Benita Renate (1935–2012).

Military service and training

Gurlitt was an officer in the German Army from 1914 to 1918 . He was wounded three times while serving in the First World War . He then studied art history , first at the TH Dresden , from 1919 at the Humboldt University in Berlin and then at the Art History Institute of the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main . There he was in 1924 with a dissertation on the architectural history of St. Catherine's Church in Oppenheim at Rudolf Kautzsch Dr. phil. PhD.

Museum management - commitment to avant-garde art

From April 1, 1925 to April 1, 1930, Gurlitt was in charge of the King Albert Museum in Zwickau , which was inaugurated on April 23, 1914 . This municipal museum was built to house the council school library , the mineral collection donated in 1868 , the manuscripts of the council archives and the art objects owned by the municipality and the collection of the antiquity association. Gurlitt was the museum's first full-time director, and his appointment was to mark the beginning of the targeted development of a modern art collection. He focused on the works of avant-garde contemporary painters and organized numerous exhibitions.

In 1925, immediately after his appointment, he presented works by Max Pechstein in a large exhibition, from which he also acquired works for the museum. In 1926 the focus was on Käthe Kollwitz and the young Dresden, in 1927 works by Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff were shown and in 1928 an exhibition was dedicated to Emil Nolde . At the same time Gurlitt was interested in the works of the painters Oskar Kokoschka , Emil Nolde, Lovis Corinth , Max Liebermann , Max Slevogt , Ernst Ludwig Kirchner , Otto Dix , Lyonel Feininger , Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky . Gurlitt was in close personal contact with numerous artists of his time, including Ernst Barlach .

Gurlitt had the Bauhaus in Dessau design and paint the Zwickau Museum; this redesign, which was presented to the public in 1926, met with national approval. The financial resources of the museum were very modest. Therefore Gurlitt occasionally sold a traditional work from the 19th century. This and the propagation of modern art provoked increasing resistance from conservative circles in Zwickau. The local group Zwickau of the Kampfbund for German culture stood out in particular . Campaigns against Gurlitt's preferred acquisition of modern art led to his dismissal on April 1, 1930. Officially, the financial bottlenecks in the city of Zwickau were given as the reason. On the mediation of Ludwig Justi , Gurlitt became head of the Kunstverein in Hamburg in May 1931 .

time of the nationalsocialism

Dismissed as head of the art association

In Hamburg, too, the National Socialists took a stand against Gurlitt's conception of art. The Hamburger Kunstverein "promote the international and Bolshevik art course" announced the National Socialist sculptor and high functionary of the Kampfbund for German Culture , Ludolf Albrecht , who was appointed on March 5, 1933 as a representative of the already harmonized Reich Association of Visual Artists Germany Gau Northwest Germany . Gurlitt was able to hold an exhibition of modern Italian art in April 1933 - with temporary support from the National Socialist First Mayor of Hamburg , Carl Vincent Krogmann , who had been in office since March 8 - in which he also housed modern German works. But the pressures soon became too strong because, among other things, Gurlitt's supporter Krogmann, who was not averse to modern art, was pursuing his own National Socialist goals and giving up Gurlitt's protection. Krogmann began to align the art association. Gurlitt was forced to resign on July 14, 1933. His successor was the art historian Friedrich Muthmann .

Art dealer in Hamburg

After his release, Gurlitt set up shop in Hamburg with the company Kunstkabinett Dr. H. Gurlitt self-employed as an art dealer . The business premises were briefly at Klopstockstrasse 35 and then at Alten Rabenstrasse 6 in Hamburg-Rotherbaum until the house was destroyed in the Second World War . Gurlitt was very successful. "He offered the best, internationally respected art by older and younger masters, modern art, but also 'degenerate' under the hand." Since the trade in "degenerate art" was forbidden, Gurlitt "allegedly" carried out this business in a basement room so that no one was aware of the illegal processes.

In 1937 there was a scandal over an exhibition of paintings by Franz Radziwill , which Gurlitt organized in the rooms of his art gallery. Radziwill was a member of the NSDAP and had exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1934. In 1935 Radziwill had fallen out of favor with parts of the NSDP. His pictures were considered too modern. He had to temporarily give up his professorship at the Düsseldorf Art Academy. Pictures of him were confiscated and exhibitions closed. In 1937 he was actually rehabilitated again. At the opening, radical students in the Nazi student union turned against Radziwill, against Professor Wilhelm Niemeyer from the art college, who gave the opening lecture, and against Gurlitt. In this context, Gurlitt was threatened with the closure of his gallery.

In 1937 Gurlitt tried to win Ernst Barlach for the design of the tympanum of the Petrikirche in Hamburg , which Barlach refused so as not to cause trouble for his patrons like Hermann F. Reemtsma . Gurlitt also wanted to have a font for the Johanneskirche in Hamm designed by Barlach. In 1942 he gave up his Hamburg residence and moved to Dresden.

Trade in confiscated "degenerate art"

Four art dealers were appointed for the sale of confiscated “degenerate art”, known as the “recovery campaign”, among them, in addition to Gurlitt, Karl Buchholz , Ferdinand Möller and Bernhard A. Böhmer . The sales and barter deals took place between 1938 and 1941. According to the knowledge that Meike Hoffmann gained during her research into the activities of Bernhard A. Boehmer, Gurlitt took over works on paper and paintings, but no images (sculptures and sculptures) from the confiscated property.

Gurlitt also sold confiscated works to domestic collectors. The Sprengel Collection benefited from this . Karl Schmidt-Rottluff's marshland with a red wind turbine was one of the acquisitions that Bernhard and Margit Sprengel made on this route .

The confiscation of works of art of "degenerate" art was justified by the law on confiscation of products of degenerate art of May 31, 1938. This decreed that corresponding works of art could be confiscated in favor of the Reich without compensation if they had previously been in the property of Reich citizens or domestic legal entities. Some of these works of art were burned. Works of art that were believed to be able to be sold abroad for foreign currency were collected at Schönhausen Palace . The whereabouts of many works of art that changed hands at the time or were stored in the cellar of the Propaganda Ministry remained unclear.

An ostracized expressionist painting from the “Chamber of Horrors” of the Moritzburg Museum , Franz Marc's Tierschicksale from 1913, Gurlitt sold in May 1939 for 6000 Swiss Francs to the Kunstmuseum Basel and received a commission of 1000 Swiss Francs. In a secret operation in 1939 , the art dealer August Klipstein and Gurlitt brokered several Vasili Kandinsky paintings that had been confiscated as “degenerate art” in the United States.

Art acquisition in France for the special order Linz

In 1943, the new head of the special order Linz appointed Hermann Voss Gurlitt as his main buyer in France. Gurlitt thus rose to become an influential player in the special order for Linz.

In occupied France, various organizations were involved in the theft of art belonging to Jews, Freemasons and people who were considered enemies of the state by the Nazi authorities. The largest of these robbery organizations, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg , whose deputy head, Bruno Lohse , also acted as the chief purchaser of French art for the Göring Art Collection , was the German embassy in Paris at the beginning of the occupation, and also at the beginning of the occupation The Künsberg special command of the Foreign Office and the Linz special order. Art has also been stolen from public and private French possession. The justification for this was the attempt to reverse the allegedly unlawful removal of works of art by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1806. The art protection department of the German occupation administration also took part in the theft of art for a time by confiscating art objects from Jewish property and handing them over to Reichsleiter Rosenberg's operational staff. Confiscated works that were not needed by the big robbery organizations were also given to the art trade in Paris. Therefore, stolen works of art were sometimes also available in normal stores. Gurlitt also bought pictures there, which were often stolen works of art.

post war period

After the " Dresden Bombing Night " in February 1945, the Gurlitts family temporarily lived with his mother in Possendorf near Dresden. Gurlitt fled from there with his wife and two children and arrived on March 25, 1945 in a truck at the castle of Baron Gerhard von Pölnitz , whom he knew from Berlin and Paris, in Aschbach near Bamberg . American troops reached Aschbach on April 14, 1945. Von Pölnitz, who headed the NSDAP 's local branch, and the art dealer Karl Haberstock , who was also registered in the palace, were arrested. Gurlitt was picked up by the US Army and placed under house arrest.

According to Gurlitt's sworn testimony, he had transported boxes of works of art from his possession on the truck, which he had previously deposited in various places in Saxony. The boxes were confiscated by the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Section special unit , first brought to Bamberg and then kept at the Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point . Gurlitt initially stayed in Aschbach and lived in the castle's forester's house. He later traveled afterwards and tried to get the pictures published, which he succeeded in five years later, in 1950.

The Monuments Men , as the special unit was called, were essentially interested in returning looted art that had reached Germany from one of the occupied countries to the respective country of origin - in order then to leave it to the authorities of the countries of origin to deal with the individual restitution employ. At the beginning of June 1945 Gurlitt was questioned in Aschbach by US Lieutenant Dwight McKay about his role as a Nazi art dealer. According to the minutes of this questioning, Gurlitt described how he had been hired by the head of the Linz special order, Hermann Voss , in early 1943 to help him buy works of art for the Führer Museum in occupied Paris. Gurlitt denied any involvement in the looted art trade in France. According to a report in the Süddeutsche Zeitung in 2013, the Allies' investigations did not focus on "degenerate art", modernity, which Hildebrand Gurlitt had traded abroad with the official permission of the National Socialists, but on works of French provenance. Works by Courbet, Oudry and Degas, all of which were allegedly legally acquired in the Paris art trade in 1942, are said to have suggested suspicion of looted art.

In the post-war period, Gurlitt went through a denazification process . According to his judicial chamber file, Gurlitt stated a taxable income of 178,000 Reichsmarks for 1943 and assets of 300,000 Reichsmarks for 1945. The examining authorities, however, determined a fortune of 450,000 Reichsmarks for 1945. The rehabilitation was achieved through an acquittal by the Bamberg-Land ruling chamber in June 1948 because he was able to assert his Jewish origins, his non-membership of Nazi organizations and his commitment to modern art. One of the exonerating witnesses was Max Beckmann . Evidence for this is a file found in Coburg, the content of which was reported in the Coburger Tagblatt in November 2013. In 1947 Gurlitt resumed his contacts with other art dealers and obviously tried to use his knowledge of the whereabouts of works of art during the Nazi era. Then in 1948 he became head of the art association for the Rhineland and Westphalia in Düsseldorf .

Death and honor

Hildebrand Gurlitt died on November 9, 1956 as a result of a car accident on the motorway near Oberhausen. Two weeks earlier he had gotten under a truck with his DKW on a return trip from Berlin to Düsseldorf and has been in a coma ever since. Gurlitt had suffered from a cataract and was considered an unsafe road user. He was buried in the Düsseldorf North Cemetery .

On January 24, 1957, Leopold Reidemeister gave a speech in memory of Hildebrand Gurlitt at the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen. In 1965 a street in Düsseldorf was named after Hildebrand Gurlitt.

Gurlitt Collection

Hildebrand Gurlitt also created a private collection of works, predominantly of classical modernism. This included, for example, Paul Klee's painting Swamp Legend from 1919, which was confiscated from the Provincial Museum in Hanover in 1937, but was on loan from Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers . After the picture had been mockingly shown in the “ Degenerate Art ” exhibition, Gurlitt took it over - like many other works of art - from this inventory and finally bought it in 1941 for 500 Swiss francs for his own collection.

Parts of the Gurlitt collection were confiscated by the Allies in Aschbach Castle in 1945 and kept at the Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point , but returned in 1950. In 1945/46 he returned Max Liebermann's painting Wagen in den Dünen by Max Liebermann, which he had acquired from the possession of the Hamburger Kunsthalle . He was one of the lenders at the first exhibition of paintings by the Blue Rider after the Second World War in 1949 in Munich. In 1956 pieces from Hildebrand Gurlitt's collection were exhibited as part of the German Watercolors exhibition in New York, San Francisco and Cambridge.

In February 2012, 1,280 works, mostly works on paper, as well as framed pictures, most of which had disappeared since the Nazi era, were discovered and confiscated by customs officers in the Munich apartment of Gurlitt's son Cornelius . According to media reports, these should include around 300 works that were confiscated in German museums as so-called “degenerate art” from 1937 onwards, and another 200 works that were searched for as Nazi-looted art ; this number has not been confirmed by the prosecution. The works of the masters of classical modernism are particularly valuable: Marc Chagall , Ernst Ludwig Kirchner , Paul Klee , Oskar Kokoschka , Franz Marc , Henri Matisse and Emil Nolde . After the end of the Second World War, Gurlitt and in the 1960s his widow described the pictures he had kept as being burned in the war. The art historian Meike Hoffmann from the “Degenerate Art” research center at the Free University of Berlin was commissioned to determine the origin and value of the works. The find was only known to the public in early November 2013. Among other things, Max Liebermann's Two Riders on the Beach , the David Friedmann collection until 1939 , Breslau, and Franz Marc's horses in landscape were shown at the press conference on the Schwabing art find. The former owner of the Marc watercolor until 1937 was the Moritzburg Art and Industry Museum in Halle (Saale) .

Between the beginning of February and the end of March 2014, the representatives of Gurlitt's son Cornelius announced that a total of 238 additional works of art from the collection, including 39 oil paintings, had been discovered in a Salzburg house by Cornelius Gurlitt and that the latter intended to steal works that were stolen from Jewish property to be returned to the owners or their heirs.

At the beginning of September 2014 it became known that another painting by Claude Monet (possibly around 1864) was found in Gurlitt's effects .

On November 6, 2013, the Austrian art historian Alfred Weidinger was astonished at the alleged discovery of this collection; its existence and dimensions were known to all art historians in southern Germany.

Publications

- Building history of the Katharinenkirche in Oppenheim a. Rh. Frankfurt, Phil. Diss., 1924.

- Introduction and text accompanying the reprint based on the copy in the Prussian State Library by Peter Paul Rubens, Palazzi di Genova 1622 , Berlin 1924. (online)

- The city of Zwickau. Förster & Borries, Zwickau 1926.

- From old Saxony. B. Harz, Berlin 1928.

- To Emil Nolde's watercolors. In: Art for everyone. Munich 1929, p. 41. (digitized version)

- The Katharinenkirche in Oppenheim a. Rh. Urban-Verlag, Freiburg i. Br. 1930.

- Museums and exhibitions in medium-sized cities . In: Das neue Frankfurt, international monthly for the problems of cultural redesign , Frankfurt 1930, p. 146. (online)

- New English painting . In: Die neue Stadt, international monthly for architectural planning and urban culture , Frankfurt am Main 1933, p. 186. (online)

- Wilhelm Buller Collection. Art Association for the Rhineland and Westphalia, Düsseldorf 1955.

- Richard Gessner. Friends of Main Franconian art and history, Würzburg 1955.

literature

- Andreas Baresel-Brand, Nadine Bahrmann, Gilbert Lupfer (eds.): Art find Gurlitt. Ways of Research , De Gruyter, Berlin 2020, ISBN 978-3-11-065813-2 .

- Maike Bruhns : Art in Crisis. Vol. 1: Hamburg Art in the “Third Reich”. Dölling and Galitz, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-933374-94-4 .

- Anja Heuss: art and cultural property theft. A comparative study on the occupation policy of the National Socialists in France and the Soviet Union. Winter, Heidelberg 2000, ISBN 3-8253-0994-0 (also dissertation , University of Frankfurt am Main 1999).

- Meike Hofmann and Nicola Kuhn: Hitler's art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt 1895–1956. The biography . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-69094-5 .

- Stefan Koldehoff : The pictures are among us. The business with Nazi-looted art and the Gurlitt case , Galiani, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-86971-093-8 .

- Michael Löffler: Hildebrand Gurlitt (1895–1956), first Zwickau museum director. Zwickau Municipal Museum , Zwickau 1995.

- Kathrin Iselt: Special representative of the Führer: the art historian and museum man Hermann Voss (1884–1969). Cologne, Weimar, Vienna, Böhlau 2010, ISBN 978-3-412-20572-0 .

- Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany , Kunstmuseum Bern (Hrsg.): Gurlitt inventory . Hirmer, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-7774-2962-5 .

- Isgard Kracht: In action for German art. Hildebrand Gurlitt and Ernst Barlach. In: Maike Steinkamp, Ute Haug (ed.): Works and values. About trading and collecting art under National Socialism. (= Writings of the research center “Degenerate Art” 5) Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-05-004497-2 , pp. 41–60.

- Leopold Reidemeister: In memoriam Dr. Hildebrand Gurlitt: b. September 15, 1895, died November 9, 1956. Commemorative speech given at the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen on January 24, 1957. Düsseldorf 1957.

- Katja Terlau : Hildebrand Gurlitt and the Art trade during the Nazi Period. In: Vitalizing Memory. International Perspectives on Provenance Research. American Association of Museums. Washington 2005, pp. 165-171.

- Vanessa-Maria Voigt: Art dealer and collector of the modern age during the National Socialism. The Sprengel Collection 1934 to 1945. Reimer, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-496-01369-3 , pp. 130–155.

- Catherine Hickley: “The Munich art hoard. Hitler´s dealer and his secret legacy ", Thames & Hudson Ltd., London 2015, ISBN 978-0-500-25215-4 (translation into German 2016).

- Jens Griesbach: Discovered: Letters from Nazi art dealers . In: Uetersener Nachrichten . October 18, 2016, p. 23. Mail bag with letters from Gurlitt and Bernhard A. Böhmer found in Güstrow .

Web links

- Literature by Hildebrand Gurlitt in the catalog of the German National Library

- Portrait photo Hildebrand Gurlitts (around 1930) , Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , September 9, 2008

- Documents on Hildebrand Gurlitt at Lost Art , Magdeburg coordination office

- Susanne Altmann: The Gurlitt case. The victim-perpetrator profile. From savior to profiteer: How Hildebrand Gurlitt got his art collection , in: art - Das Kunstmagazin , issue 1/2014

- Flavia Foradini: The Gurlitt collection should be sold to benefit Jewish organizations , The Art Newspaper, online edition 20th Nov 2014 (English)

- Flavia Foradini: The other Gurlitt: the dealer cherished by 'degenerate' artists and Nazis alike , The Art Newspaper , January 2015 (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ "Dr. H. Gurlitt died " , press release of the Art Association for the Rhineland and Westphalia of November 9, 1956 (" on November 9, in the morning at 6.30 a.m., in the Josephs Hospital in Oberhausen-Sterkrade ")

- ↑ His grandmother Elisabeth Lewald (1822–1909) was the daughter of the Jewish merchant David Marcus (1787–1846) and his wife Zippora (née Assur, 1790–1841). After the Prussian Jewish edict of 1812 , the father and with him the family were baptized (Protestant), dropped the Jewish-sounding name Marcus and called himself, in Prussian terms, "Lewald". After David's brothers August, Markus and Friedrich had given up the name Marcus and adopted the family name Lewald, he also officially changed his name. In 1838 David Marcus Lewald was elected honorary city councilor of Königsberg for six years.

- ↑ Hedwig Müller: Mary Wigman. Life and work of the great dancer. Edited by the Berlin Academy of the Arts. Quadriga, Weinheim 1986 ISBN 3-88679-148-3 , p. 75

- ^ Phantom Collector: The Mystery of the Munich Nazi Art Trove. spiegel.de/international, November 11, 2013, accessed on November 19, 2013.

- ↑ Maike Bruhns : Art in the Crisis. Vol. 1: Hamburg Art in the “Third Reich”. Dölling and Galitz, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-933374-94-4 , p. 590.

- ^ Pressure Mounts to Return Nazi-Looted Art. New York Times

- ^ Document from 1948: Biographical Declaration of Dr. Hildebrand Gurlitt

- ↑ See Fig. Sworn Statement Dr. H. Gurlitt 1945

- ^ Dissertation in the catalog of the German National Library.

- ^ History of the collection ( Memento from November 6, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Website of the Zwickau Art Collections.

- ↑ Vanessa-Maria Voigt: Art dealers and collectors of the modern age under National Socialism. The Sprengel Collection 1934 to 1945. Reimer, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-496-01369-3 , p. 134.

- ↑ In detail: Maike Bruhns: Art in the crisis. Vol. 1: Hamburg Art in the “Third Reich”. Dölling and Galitz, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-933374-94-4 .

- ↑ Maike Bruhns: Art in the Crisis. Vol. 1: Hamburg Art in the “Third Reich”. Dölling and Galitz, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-933374-94-4 , p. 102.

- ↑ Mark Nixon: Samuel Beckett's German Diaries 1936–1937. London / New York 2011, note 15.

- ↑ Maike Bruhns: Art in the Crisis. Vol. 1: Hamburg Art in the “Third Reich”. Dölling and Galitz, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-933374-94-4 , p. 227.

- ↑ a b Stefan Koldehoff: The pictures are among us. The Nazi-looted art business and the Gurlitt case. Galiani, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-86971-093-8 , p. 27.

- ↑ a b Isgard Kracht: The Fight for German art. Hildebrand Gurlitt and Ernst Barlach. In: Maike Steinkamp, Ute Haug (ed.): Works and values. About trading and collecting art under National Socialism. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-05-004497-2 , p. 53.

- ^ A b Maike Bruhns: Art in the Crisis. Vol. 1: Hamburg Art in the “Third Reich”. Dölling and Galitz, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-933374-94-4 , p. 591.

- ↑ See also: Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers

- ↑ Meike Hoffmann : Trade in “degenerate art”. In: Active Museum of Fascism and Resistance in Berlin : Good Business - Art Trade in Berlin 1933–1945. Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-00-034061-1 , pp. 144-145.

- ↑ Ruth Heftrig, Olaf Peters , Ulrich Rehm (eds.): Alois J. Schardt. An art historian between the Weimar Republic, “Third Reich” and exile in America (= writings on modern art historiography , volume 4). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-05-005559-6 , p. 98.

- ↑ Meike Hoffmann (Ed.): A dealer of “degenerate” art: Bernhard A. Böhmer and his estate. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-05-004498-9 . (= Writings of the research center “Degenerate Art” 3.), p. 211.

- ↑ Vanessa-Maria Voigt: Art dealers and collectors of the modern age under National Socialism. The Sprengel Collection from 1934 to 1945. Reimer, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-496-01369-3 , pp. 142–149.

- ^ Database "Degenerate Art" of the Free University of Berlin

- ↑ Felix Bohr, Özlem Gezer, Lothar Gorris, Ulrike Knöfel, Sven Röbel, Michael Sontheimer and Steffen Winter: Das Phantom . In: Der Spiegel . No. 46 , 2013, p. 153 ( online - November 11, 2013 ).

- ↑ The winding path of Kandinsky's «Three Sounds». Bern newspaper .

- ↑ Kathrin Iselt: Special Representative of the Führer: The art historian and museum man Hermann Voss (1884–1969). Böhlau, Cologne 2010, ISBN 978-3-412-20572-0 . P. 289.

- ↑ Anja Heuss: Art and cultural property theft. A comparative study on the occupation policy of the National Socialists in France and the Soviet Union. Winter, Heidelberg 2000, ISBN 3-8253-0994-0 , p. 116.

- ↑ a b c d Sworn statement by Dr. H. Gurlitt of June 10, 1945 , PDF, 11 pages

- ↑ Americans had a list of Gurlitt paintings ( memento from November 12, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), mdr.de, November 8, 2013

- ↑ Felix Bohr, Lothar Gorris, Ulrike Knöfel, Sven Röbel, Michael Sontheimer: The Art Dealer to the Führer. In: Der Spiegel, 52/2013, pp. 105–144.

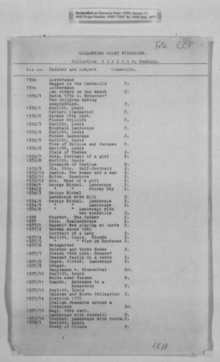

- ↑ ALIU LIST OF RED FLAG NAMES. Art Looting Intelligence Unit (ALIU) Reports 1945–1946, full text on lootedart.com.

- ^ Munich art discovery is a "political problem of the federal government". In: Deutschlandradio , November 8, 2013, accessed on November 9, 2012.

- ↑ Ira Mazzoni : The Gurlitt Collection. sueddeutsche.de, November 7, 2013, accessed on November 7, 2013.

- ^ A b c NS gallery owner: Files in Coburg. In: Coburger Tageblatt , 9./10. November 2013.

- ^ Art dealer Gurlitt was probably not a Nazi favorite . In: inFranken.de . ( infranken.de [accessed on June 3, 2017]).

- ^ Daniela Wilmes: Competition for the modern. On the history of the art trade in Cologne after 1945. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 3-05-005197-3 , pp. 174–175.

- ↑ Vanessa-Maria Voigt: Art dealers and collectors of the modern age under National Socialism. The Sprengel Collection 1934 to 1945. Reimer, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-496-01369-3 , p. 154.

- ↑ a b www.faz.net, November 11, 2013

- ↑ Vanessa-Maria Voigt: Art dealers and collectors of the modern age under National Socialism. The Sprengel Collection 1934 to 1945. Reimer, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-496-01369-3 , pp. 138-139 with details.

- ↑ Lost family treasure . ( Memento of December 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), zdf.de, November 9, 2013, accessed on November 30, 2013

- ↑ Süddeutsche Zeitung of November 6, 2013: Allies confiscated Gurlitt works after the end of the war. List of images from the US National Archives .

- ^ Julia Voss: Looted art: indulgences with the modern. faz.net, November 27, 2013, accessed December 7, 2013.

- ↑ German watercolors, drawings and prints [1905-1955]. A midcentury review, with loans from German museums and galleries and from the collection Dr. H. Gurlitt. American Federation of Arts, New York 1956.

- ↑ Breakdown series Too many questions remain unanswered ( Memento from November 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) br.de, November 20, 2013, accessed November 20, 2013

- ^ Art find in Munich. Munich art finds contain previously unknown works. In: zeit.de, November 5, 2013.

- ↑ gurlitt.info press release of March 26, 2014 ( memento of April 1, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on March 27, 2014

- ↑ Gurlitt wants to return pictures. Süddeutsche.de , March 26, 2014, accessed on March 26, 2014 .

- ↑ Taskforce “Schwabinger Kunstfund”: Gurlitt still had a Monet in his suitcase. Report from Deutschlandradio Kultur , September 5, 2014.

- ^ Courier dated November 6, 2013

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gurlitt, Hildebrand |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gurlitt, Paul Theodor Ludwig Hildebrand (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German art historian and art dealer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 15, 1895 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Dresden |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 9, 1956 |

| Place of death | Dusseldorf |