Schwabing art find

The Schwabinger Kunstfund (also called Münch (e) ner Kunstfund or Kunstfund in Munich ) is a collection of 1280 works of art from the possession of Cornelius Gurlitt (1932–2014), son of the art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt (1895–1956). Some of the works have been considered lost since 1945; others were unknown in art history research, including a work by Marc Chagall . 499 works were initially suspected of being Nazi-looted art . So far, however, this has only been proven in five cases.

The framed and unframed pictures were confiscated from February 28 to March 2, 2012 in Cornelius Gurlitt's Schwabing apartment as part of an investigation by the Augsburg public prosecutor . This was kept secret by the investigating public prosecutor's office and only became known to the public through a report by the news magazine Focus on November 3, 2013, in which an art discovery was reported. The seizure and subsequent publication of the private collection is described by some lawyers as unlawful. Later discoveries in Salzburg increased the publicly known total of the so-called Gurlitt Collection to over 1500 works of art.

history

Triggers the investigation

In September 2010, Cornelius Gurlitt was checked by German customs investigators on the train from Zurich to Munich. The customs administration has the task of monitoring the movement of cash that is brought into or out of the European Community ( Section 1 (3a) of the Customs Ordinance - Customs Administration Act). At the request of the customs officials, persons must report cash worth 10,000 euros or more and explain its origin ( Section 12a, Paragraph 2 of the Customs Ordinance). If necessary, the persons can be physically searched at a suitable location ( Section 10 (3) Customs Ordinance). Gurlitt is said to have stated in response to a question from the customs investigator that he did not carry any cash with him. It can be assumed that the officer correctly asked for cash over the limit and Gurlitt said no. During a body search on the train toilet, the officers discovered 9,000 euros. Gurlitt gave his personal details and his Munich address. When the investigators investigated the suspicion of a black money account in Switzerland, it was found that Gurlitt was not registered in Munich and had neither bank details nor social security.

In September 2011, the Augsburg public prosecutor obtained a judicial search warrant , on the basis of which at the end of February 2012 Gurlitt's apartment was searched and his art collection was confiscated. The content of the search warrant is unknown, but it is alleged to contain allegations of tax offenses and embezzlement. In any case, it must regularly contain the allegation and identify the evidence sought ( § 102 ff StPO).

The Chief Public Prosecutor Reinhard Nemetz of the Augsburg Public Prosecutor stated in November 2013 that the pictures were not found by chance. They "searched specifically in connection with the tax criminal investigation and then took away everything that seemed prima facie to be relevant to the evidence."

However, the public prosecutor's office subsequently refused to provide further information on the alleged criminal offenses and the preliminary investigation.

Seizure of the collection

The works of art were confiscated in the context of investigations by the Augsburg public prosecutor's office on account of “a criminal offense subject to tax secrecy ” and on suspicion of embezzlement in Gurlitt's private apartment in Munich- Schwabing . In contrast to the first reports, there were not 1400 to 1500 works, but 1280. In the course of the search, the entire collection was confiscated. The legal basis of the seizure is controversial. In December 2013 the art expert Sibylle Ehringhaus requested the return of all pictures to Gurlitt.

On November 9, 2013, the police in Kornwestheim in Baden-Württemberg seized another 22 paintings from the house of Cornelius Gurlitt's brother-in-law, Nikolaus Fräßle, at Fräßle's request because he feared for the safety of the works of art. The police have no evidence of a criminal act.

Formation of a working group and publication of works suspected of being looted

On November 11, 2013, the Bavarian Ministry of Justice announced that, together with the Bavarian Ministry of Culture , the Federal Ministry of Finance and the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture, a working group (“task force”) of at least six experts for provenance research would be put together under the direction of Ingeborg Berggreen-Merkel . Her goal is to create transparency and to continue researching the provenance. In addition, works suspected of being looted would be published on the platform of the Magdeburg coordination office . The legality of this publication is in doubt.

According to the Federal Criminal Police Office , around 970 works are to be checked, minus confiscated objects that clearly have no relation to “degenerate art” or Nazi-looted art. Of these, around 380 works can be classified as “degenerate art”, and around 590 works must be checked to see whether they were illegally acquired or expropriated during the Nazi era. According to a report from the world , 13 of the 25 works published so far on the aforementioned platform belonged to the Dresden lawyer Fritz Salo Glaser (1876–1956). The still incumbent Minister of State for Culture, Bernd Neumann , announced that more works would be added to the online directory.

The head of the working group announced on November 14, 2013 that hundreds more paintings from the art treasure would be posted on lostart.de in a few days. The Augsburg public prosecutor will announce all around 590 works that are considered to be possible Nazi looted property. After a first, not yet legally binding court decision at the end of January 2014, the press has a right to the complete list of all paintings confiscated from Cornelius Gurlitt.

In the media, the work of the task force is viewed rather critically, as the provenance of only 11 of the 500 images could be clarified by the beginning of 2016, the rightful owner of only five could be determined, only two images have been returned so far. Time evaluates the result as a result of incorrect expectations:

“The term task force should signal determination, downright military assertiveness. A political instrument was thus created - and it was forgotten how tedious scientific provenance research is. The disappointment was programmed. "

New law in planning

At a cabinet meeting on January 7, 2014, the Bavarian Justice Minister Winfried Bausback announced the draft for a law on the return of cultural property (colloquially: "Lex Gurlitt"), which was presented to the Federal Council on February 14 . Claims for the return of legal heirs of victims of Nazi art policy should no longer automatically expire after 30 years. The prerequisite is that the current owner is " bad faith ", that is, an owner of so-called looted art must have at least evidence at the time of acquisition that the work of art did not legally belong to the seller.

Securing works in Salzburg

On February 10, 2014 Gurlitt's spokesman Stephan Holzinger announced that more than 60 works of art had been seized from Gurlitt's house in Salzburg , including Marine, temps d'orage by Édouard Manet and works by Claude Monet , Auguste Renoir and Pablo Picasso . His supervisor, lawyer Christoph Edel, arranged for the seizure to be carried out in order to protect the works from burglary and theft; they should also be examined for their origin. At the end of March 2014, Gurlitt's lawyers and representatives announced that the Salzburg part of the Gurlitt Collection was four times as large as previously assumed and comprised a total of 238 works of art - including 39 oil paintings. The other works were located in parts of the building that were previously inaccessible. The total number of known works in the Gurlitt Collection increased to around 1,500 works of art. To distinguish these works, one also speaks of the Salzburg art find.

Agreement between Gurlitt and the authorities

According to media reports, an agreement was reached between Gurlitt, the Bavarian Ministry of Justice and the federal government in April 2014 . Gurlitt then made all works deemed to be contaminated available for provenance research for one year. The federal government and the state of Bavaria are to bear the costs of this research. In the case of any works with withdrawal due to Nazi persecution, a fair and equitable solution is sought with the claimants. This agreement will remain in effect even after the death of Cornelius Gurlitt on May 6, 2014 and will pass to his heirs.

Kunstmuseum Bern as heir to the collection

On May 7, 2014, the foundation of the Kunstmuseum Bern announced in a statement that it had been appointed sole heir in Cornelius Gurlitt's will . According to a report in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung , however, it was unclear which works would be transferred to Bern and when . First, the will must be checked for validity. Bavarian authorities assumed that the foundation was bound by the agreement signed by Gurlitt. This means that all works that are suspected of being looted will remain in Germany for at least one year. On the other hand, according to the report, all works classified as “harmless” could be transferred to Bern in 2014 after examining the will. As Gurlitt's legal successor, the Kunstmuseum Bern Foundation (KMB) is the new contact for the task force set up by the federal government and for the heirs of previous owners. The Board of Trustees had to decide within six months whether the inheritance would be accepted. According to museum director Matthias Frehner, the problems of the collection were discussed during the legally stipulated period . A distant relative has announced that the family will contest the as yet unopened will if the family is ignored.

On November 22, 2014, the Board of Trustees of the Kunstmuseum Bern decided to take on the Gurlitt estate, which was made public two days later at a press conference in Berlin. 440 pictures that were classified as "degenerate art" and 280 pictures that were created by Gurlitt's relatives or acquired after 1945 are to be transferred to Bern immediately. A separate research center is also to be founded in Bern. Suspicious works of art should remain in Germany until their provenance and possible applicants have been clarified. Exhibitions should help to clarify. Germany takes on the legal costs for possible restitutions and disputes and also takes responsibility for the Salzburg Fund.

In December 2016, a judgment was passed on the Gurlitt inheritance: A cousin had doubted that Cornelius Gurlitt was capable of making a will at the time his will was drawn up. The competent higher regional court ruled, however, that there were no sufficient indications for this; the will is therefore valid, the collection must be handed over to the museum in Bern.

Around 400 works from the find were exhibited in 2017/2018, some of them in parallel at the Kunstmuseum Bern and the Bundeskunsthalle Bonn . The focus of the double show was on the subjects of “degenerate art” and looted art.

Ownership assessment

The legal assessment of property rights to art objects, which the National Socialists described as "degenerate" and removed from public museums or confiscated from often Jewish owners, is complex. Carl-Heinz Heuer sums up the situation as follows: As morally unsustainable as the persecution of “degenerate” art was, from a legal point of view no restitution could be demanded. Not only the confiscation from state museums, but also the expropriation from private collections, despite all their reprehensibility, are effectively legal acts of the German Reich, which is dominated by National Socialist rule. What remains is solely a moral dimension.

The legal historian Uwe Wesel declared on December 1, 2013 on Deutschlandfunk that Gurlitt was the legal owner of all works confiscated from him. Today there is no longer any possibility of doing justice to the original owners. Immediately after the Second World War, the Allies had legally regulated that claims for restitution by the original owners were excluded (MilRegG No. 59). However, this statutory ordinance only concerned the British zone of occupation, and the document does mention cases of mandatory reimbursement. Wesel continues, however, that it is unfortunately the case that today's lawyers are often no longer familiar with these Allied laws. The public prosecutor's office in Augsburg therefore probably made serious legal errors out of ignorance and was guilty of a breach of official duty . The seizure and publication of the pictures in the lost art database are not lawful. He sees it as a state liability case , so that Gurlitt can claim compensation from the state for the damage he suffered from all this.

Legal basis

The Munich film producer, director and author Maurice Philip Remy has in his book The Gurlitt. The true story of Germany's biggest art scandal, the question of the legal basis for restitution of stolen art, presented in detail on a case-by-case basis . He referred to Jürgen Lillteicher's Freiburg dissertation , a brochure initiated by the historical commission of the party executive committee of the SPD and published by the Hamburg historian Barbara Vogel , a newspaper commentary by the lawyer Uwe Wesel , a legal opinion by Johannes Wasmuth and the documentation of the organizer of the Washington declaration and US Ambassador Stuart E. Eizenstat . Remy found that the seizure of the Gurlitt collection by the Augsburg public prosecutor's office was not legally legitimized.

Allied Military Government Laws

The only ever existing legal basis was the American Military Government Act No. 59 of November 10, 1947, which was largely adopted by the British and French occupation forces through their own regulations. The law basically assumed a loss of property due to persecution if a transfer was made after January 30, 1933; there was therefore a reversal of the burden of proof . However, the claims could only be registered within a reporting period of one year, since the Allies did not want to endanger the reconstruction of the country by prolonged legal uncertainty. On June 30, 1950, however, it was finally over. Claims that had not been submitted until then were forfeited forever. Subsequent civil law prosecution was expressly excluded. The legal advisor of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation , Carola Thielecke, gives a deadline for December 31, 1969, which, however, is based on the later Federal Restitution Act .

Refund Act

In July 1957, the German Bundestag passed the Federal Restitution Act ; it only settled material damage, not a refund. According to Remy , the law ... lagged well behind the military government law ...; it was determined that a loss of wealth through sale should not be made up, even if it was under pressure to pay compulsory taxes. Thus ... a substantial part of the lost works of art was excluded from financial compensation. This also applied to the area of the former GDR. On December 23, 1990, the People's Chamber passed the law regulating open property issues - Property Act - (VermG) of September 23, 1990, the implementation of which was finally transferred to the Federal Office for Central Services and Unresolved Property Issues (BADV) as a continuing law . The registration deadline was June 30, 1993.

Washington and subsequent declarations as voluntary commitments

In November 1998, was in DC Washington, in the United States Department of State ( United States Department of State ) and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has been advised (USHMM) supported conference, how to deal with during the Nazi era were made Jewish losses of artistic heritage , Books, archives as well as insurance and other property claims. This resulted in the Washington Declaration (Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art) , which listed eleven points of principles of a just and fair solution . On December 14, 1999 followed the joint declaration of the federal government, the federal states and the central municipal associations on the discovery and return of cultural property seized as a result of Nazi persecution, in particular from Jewish property (joint declaration) . This declaration only applies to public institutions and is legally non-binding. For private institutions and collectors, the declaration only had the character of a well-intentioned recommendation . In June 2009 the Prague Conference on Holocaust Issues followed, in which 46 nations took part. It concluded with the Theresienstadt Declaration, which was based on the Washington principles with regard to the handling of looted art. In November 2018, the Washington principles were finally affirmed in a binational joint declaration in Berlin.

On January 1, 2015, the German Center for the Loss of Cultural Property was established as a foundation under civil law by the federal government, the federal states and the three central municipal associations. The center has been responsible for the Gurlitt provenance research since 2016 and is therefore legally responsible for handling the collection.

Works

scope

According to the Augsburg public prosecutor's office , the collection consists primarily of paintings , gouaches , drawings and prints from the Classical Modern period and the 20th century, including by Max Beckmann , Marc Chagall , Otto Dix , Ernst Ludwig Kirchner , Oskar Kokoschka , Max Liebermann , August Macke , Franz Marc , Henri Matisse , Emil Nolde , Pablo Picasso and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff . But works from the 19th century to works from the 16th century have also been found, for example by Canaletto , Gustave Courbet , Pierre-Auguste Renoir , Carl Spitzweg and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec . A self-portrait by Dix and a previously unknown work by Chagall are particularly valuable in terms of art history.

value

Journalists - in ignorance of the found works - gave around one billion euros as the current market value in initial estimates. After the approximate holdings of the collection became known, art dealers estimated the value of the collection at a maximum of 50 million euros.

exploration

The art historian Meike Hoffmann from the “Degenerate Art” research center at Berlin's Free University was initially entrusted with determining the images and their provenance .

In addition, the Institute for Art History and the Faculty of Law at the University of Regensburg organized a symposium in 2015 with the title Gurlitt - What Now? .

origin

In the article “Gurlitt - What Now? Considerations of a lawyer ”, the more precise course of the conference is described and the origin of the Gurlitt Collection is discussed. According to the information cited there, at least 380 of the works that have emerged belong to the exhibits confiscated in 1937 as part of the “Degenerate Art” confiscation campaign. It is assumed that 590 other works of art are potentially Nazi-looted art - works that were stolen from their former Jewish owners or sold by them as a result of persecution - as well as works of art that were created by the National Socialists as part of the so-called "Action degenerate art" from 1937 onwards they were defamed as “ degenerate ” and removed from public collections. For some works, search reports from former owners or their heirs should be available in the database of the coordination office for the loss of cultural property .

Hildebrand Gurlitt Collection

Hildebrand Gurlitt's collection mainly contained works of classical modernism . After the end of the war, parts of the collection were confiscated by the Allied forces' Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Program and kept at the Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point . In 1950, Gurlitt received 125 works of art from the Collecting Point upon request, mainly paintings, prints and drawings, including Otto Dix's self-portrait. He was also given 29 sculptures and objects, African art, Meissen porcelain and four boxes with empty picture frames. Provenance researcher Willi Korte expressed the view that it was not conclusively certain that the Collecting Point had researched the provenance of each work. Gurlitt's five-page reimbursement list also includes the painting Two Riders on the Beach by Max Liebermann, the self-portrait by Otto Dix and the gouache by Marc Chagall. In 1956 pieces from Hildebrand Gurlitt's collection were exhibited in New York , San Francisco and Cambridge as part of the German Watercolors exhibition with financial support from the Federal Republic of Germany. In November 2013, the Austrian art historian Alfred Weidinger was amazed at the alleged discovery of this collection, saying that its existence and dimensions were known to "every important art dealer in southern Germany".

According to an interview published in Der Spiegel , Cornelius Gurlitt said on November 17th that his father had legally acquired all works and that he was not willing to voluntarily return them. At the end of January 2014, his lawyer contradicted the New York Times with this representation by the Spiegel ; his client was always interested in a fair and just solution. With the publication of the total number of works found in Salzburg at the end of March 2014, Gurlitt's representatives also announced that Gurlitt intended to return works that had been stolen from Jewish property to the owners or their heirs, and that they had been instructed to make justified returns to implement.

On February 14, 2014, Gurlitt's lawyers filed a complaint against the confiscation of the art collection with the Augsburg District Court. The lawyers are demanding that the collection be returned because of formal deficiencies in the court ruling at the time. The seizure of the pictures violates the principle of proportionality.

Origin of the works

Hildebrand Gurlitt was one of four art dealers who were commissioned with the exploitation of confiscated works of art during the Nazi era . For the art dealer Ferdinand Möller, it has been proven that, contrary to the requirements of government agencies (i.e. his clients), he did not bring some of the works of art that were deemed “ degenerate ” and confiscated from the territory of the Reich, but sold them to residents or acquired them himself. The literature suspects that the other art dealers, including Gurlitt, also traded in “degenerate art” in the empire or bought it back from abroad.

Known sales

So far, only one sale from the Gurlitt collection had become known to the public. In the late summer of 2011, Cornelius Gurlitt had Max Beckmann's gouache work Löwenbändiger auctioned by the Lempertz auction house in Cologne; it was sold for € 864,000. Before the auction, it was determined that the painting came from the estate of the Jewish art dealer and collector Alfred Flechtheim (1878–1937). Cornelius Gurlitt had previously reached a comparison with the heirs of Flechtheim . In the Lempertz catalog, the information on the origin of the picture referred to the Berlin gallery Alfred Flechtheim. Flechtheim had to flee abroad from the National Socialists in 1933. The Flechtheim heirs offer their help to the task force department by sharing their experiences with Cornelius Gurlitt on the occasion of the sale.

As a result of the public attention the art find attracted, it was announced in November 2013 that a painting by August Macke , Woman with a Parrot in a Landscape (1914), was auctioned by Villa Grisebach in Berlin for almost 2.4 million euros in 2007. That is the highest price that has ever been paid for a work by Macke at an auction in Germany. This picture was also on the list of works that the Americans returned to Hildebrand Gurlitt in 1950. According to the auction house, the consignor of the work was not Cornelius Gurlitt personally.

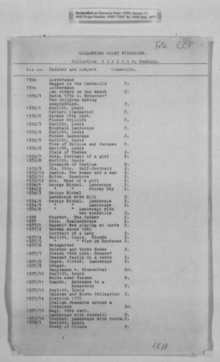

Selected works from 2013

Eleven selected works were presented to the public by the Augsburg public prosecutor at a press conference on November 5, 2013. These are:

- an etching by Canaletto with a view of Padua without any indication of the origin;

- a preliminary drawing for a painting by Carl Spitzweg: Couple making music . Hildebrand Gurlitt bought it at the beginning of January 1940 for 300 marks from the music publisher Henri Hinrichsen , who was about to flee to Brussels. The heirs are considering reclaiming;

- a hand-colored woodcut by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner: Melancholisches Mädchen , which was probably once owned by the Kunsthalle Mannheim ;

- a painting by Max Beckmann from Zandvoort and listed in the artist's catalog raisonné - this find was not discussed in detail at the press conference;

- a gouache by Franz Marc: Horses in Landscape , it was owned by the Moritzburg Art and Craft Museum in Halle (Saale) ;

- a painting by Gustave Courbet: Girl with Goat , known to be sold at auction in 1949;

- a gouache by Marc Chagall: allegorical scene not listed in the painter's catalog raisonné; it was part of the bundle confiscated by the Allies in 1945 and is listed there under the inventory number 2004/4 ; Gurlitt told the American authorities in June 1945 that the picture belonged to his sister, who was a student of Chagall; In 1950, however, he handed over a letter from the painter Karl Ballmer , in which he confirmed that he had given him both this picture and Picasso's portrait of a lady with two noses in Switzerland in 1943; on January 25, 1951, both pictures were returned to Gurlitt. In December 2013 there was another report that the picture came from the collection of the German-Jewish Blumstein family from Riga, Latvia, and had been confiscated by the Gestapo in 1941 ;

- by Henri Matisse the portrait of a seated woman, which was confiscated in 1942 by the task force Reichsleiter Rosenberg from the bank vault of the art dealer Paul Rosenberg in Libourne . His granddaughter Anne Sinclair claims the restitution of the painting. It was returned to the heirs in May 2015.

- a painting by Max Liebermann: Two riders on the beach , probably in the Friedmann Collection in Breslau until 1939 and after allied confiscation from 1945 to 1950 then in 1954 on loan from Gurlitt to the Liebermann retrospective of the Kunsthalle Bremen (restituted in May 2015), and others Drawings and sketches;

- a color lithograph with a portrait of a woman by Otto Dix;

- a painting with a self-portrait by Otto Dix, which is not listed in the painter's catalog raisonné, but was already documented in art history.

criticism

Criticism of the secrecy by the authorities

According to the Focus article from November 3, 2013, the case is said to have been classified as a "highly political secret" by the responsible authorities and ministries in Bavaria and Berlin . Noticeable is u. a. that at the beginning of September 2013 at a conference on the tenth anniversary of the “Research Center for Degenerate Art” of the Free University of Berlin, the expert Meike Hoffmann spoke of investigations on the subject of Gurlitt as a future project . In any case, the responsible public prosecutor in Augsburg referred to the tax secrecy and initially did not comment, although the find was twenty months ago. According to the lawyer and art lawyer Peter Raue , the long-term secrecy by the authorities is probably the biggest art scandal of the German post-war period . The provenance researcher Willi Korte also expressed criticism of the secrecy and suggested that the State Minister for Culture participate in the investigation.

Anne Webber, founder and board member of the London-based Commission for Looted Art in Europe , called for a list of the images to be published immediately. Your commission represents hundreds of families around the world and searches for thousands of paintings. "We need a culture of transparency and the works of art back as soon as possible."

Rüdiger Mahlo, the Germany representative of the Jewish Claims Conference founded in 1951 , which represents the compensation claims of Jewish victims of National Socialism, explained that the case and the official handling of the found works of art seemed "symptomatic of the handling of Nazi-looted art".

Reactions

The German authorities argue about who is responsible for keeping the works of art locked up for so long. According to the Bavarian Ministry of Justice in Munich, the Berlin Federal Office for Central Services and Unresolved Property Issues has been dealing with the case for a long time. The Federal Office for Central Services and Unresolved Property Issues is responsible for the return of cultural goods that could have been extorted from their owners during the Nazi era; it is part of the Finance Minister's portfolio .

Rüdiger Mahlo's criticism was successful: according to a report by the news magazine Der Spiegel on November 18, 2013, the task force panel of experts under the academic leadership of the art historian Uwe Hartmann will be expanded from originally six to ten people, including two representatives from the Jewish Claims Conference and one Representative of the public prosecutor.

Criticism of the public dealings with Cornelius Gurlitt

Journalist Julia Voss criticized the Gurlitt precedent set by the authorities and questioned its legality. Apparently, private individuals who are in possession of looted art demand more transparency than public institutions. So now a private person has to answer for years of neglect by the federal and state governments.

In a newspaper article, The Lost Honor of Cornelius Gurlitt, the art historian Daniel Kothenschulte criticized the media's reckless treatment of Cornelius Gurlitt: “Cornelius Gurlitt was not a collector, he was an heir. He wasn't a curator like his father. He sees himself as a keeper to this day, and you have to believe him, even if he was probably thinking of the general public in the end. His obvious social anxiety opposed any sense of the public. He must feel traumatic that he is now being dragged into the public eye. "

The Bernese gallery owner Eberhard W. Kornfeld , who himself was in business contact with Gurlitt, described the events surrounding the Munich art find as a media hysteria in which lurid front pages and articles are worked with without any regard for precise information. Warning voices that relativized the events would not be heard. Two standards are also measured: While Ferdinand Möller is considered a great hero and savior of “degenerate” art in Germany, Hildebrand Gurlitt is demonized for the same act and his remaining legacy is confiscated.

Accusation of political criminal justice, lack of legal basis

In an article in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on November 25, 2013 , Volker Rieble accused the Augsburg public prosecutor of perverting the rule of law in the Gurlitt case . He denied any legal basis for the confiscation of the pictures and their publication on the Internet. The public prosecutor's office has no political tasks to perform and is not called to determine the true owners of works of art. In a constitutional state, it is completely irrelevant for the public prosecutor whether property and property relations raise political questions; it basically has nothing to do with civil law claims. She was not allowed to inform potential claimants about the existence of the pictures (because by doing so she would break the "criminal procedural secrecy") nor put a picture list on the Internet, thus informing everyone about the financial situation and increasing Cornelius Gurlitt's risk of becoming a victim of a violent crime . The Federal Minister of Justice's proposal to discontinue the criminal proceedings in the event of a waiver is obscene. Only dictatorships would take advantage of criminal proceedings. The rule of law and basic rights should curb the state power precisely when it attacks the individual for a good cause and with the consent of the majority of the population.

As a result of the exhibition at the Bundeskunsthalle, Johannes Wasmuth referred Gurlitt's inventory. The Nazi art theft and the consequences in the Bonner Generalanzeiger on the Allied restitution rights : Because they expired in 1950, claims for restitution that had not been registered before were lost. So the state and the Ariseurs became the legal owners of the Nazi looted property and still are today. Under German law, therefore, Gurlitt should never have been claimed because of his collection. The handout for the implementation of the “Declaration of the Federal Government, the Länder and the Local Central Associations on the Finding and Returning of Cultural Property Stolen as a Result of Nazi Persecution, in particular from Jewish Property” , is the basis of action for LostArt.de ; It confirms this legal opinion: There it is stated that the joint declaration by the federal government, the states and the municipal umbrella organizations based on the Washington Declaration on the discovery and return of cultural property confiscated as a result of Nazi persecution does not have legal claims to the surrender of cultural property (justified) .

Report on the work of the Schwabing Art Fund Taskforce

After two years as head of the Schwabinger Kunstfund Taskforce , Ministerial Director Ingeborg Berggreen-Merkel presented the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and Media, State Minister Monika Grütters , with the 76-page report on the work of the Schwabinger Kunstfund Taskforce, including a plastic bag with data carriers to the confiscated works of art from Gurlitt's possession. This was not the expected final report of the task force , which had been pending for a year , but merely a work report or interim report, as Berggreen-Merkel told the press. The report shows that the 16 members of the task force mostly had to do their work in addition to their actual work, only met seven times in the two years and costs of 1,888,600 euros were incurred during this time. There was only one provenance researcher among the members; the rest of the people belonged to institutions from seven countries that were "at full capacity with their (local) jobs," as Michael Sontheimer noted in a mirror comment on the press conference. In this respect, "the Schwabinger Kunstfund task force ... is a blatant fraudulent label ".

The provenance of the 499 works of art to be checked could only be clarified in eleven cases, including the three works that Cornelius Gurlitt himself had negotiated with the descendants of the previous Jewish owners, as well as a portrait of his great-grandfather Louis Gurlitt , four of whom were listed in a dealer list and therefore unsuspicious pictures and a work by Jean-Louis Forain , the provenance of which emerged from a newspaper article stuck on the back.

The report, which the Süddeutsche Zeitung described in its headline the next day as a non- final report, suggests that the Gurlitt Collection “only contains about as many works with a contaminated provenance as any German museum. It is not unusual for between five and ten percent of a collection in Germany to be suspected of being looted. ”The small number of claimants named in the report is also remarkable. Although there were 200 inquiries, only 23 of them contained specific claims.

literature

- Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany , Kunstmuseum Bern (Hrsg.): Gurlitt inventory . Hirmer, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-7774-2962-5 .

- Stefan Koldehoff : The pictures are among us. The Nazi-looted art business and the Gurlitt case . Galiani, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-86971-093-8 .

- Stefan Koldehoff, Ralf Oehmke, Raimund Stecker : The Gurlitt case. A conversation . Nicolai, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-89479-863-5 .

- Annette Weber , Johannes Heil (ed.): Ersierter Kultur: the Gurlitt case . Conference publication Heidelberg 2014. Berlin: Metropol, 2015 Table of contents

- Maurice Philip Remy : The Gurlitt Case. The real story of Germany's biggest art scandal . Europe, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-95890-185-8 .

Web links

- List of works confiscated in 1945 ; National Archives documents

- Magdeburg coordination office : Schwabinger Kunstfund

- Bundestag printed matter 18/205, response of the federal government to the Schwabing art find

- Katharina Mutz and Nadine Lindner: Art discovery - The Gurlitt case and the consequences , in Deutschlandfunk - " Background " from February 13, 2014

- Agreement between the Federal Republic of Germany, the Free State of Bavaria and the Kunstmuseum Bern Foundation , dated November 24, 2014.

- Lists of works from the holdings from Munich and Salzburg , published by the Kunstmuseum Bern on November 27, 2014.

- Online archive of the Gurlitt art find ; Bundeskunsthalle database - Gurlitt inventory

Individual evidence

- ↑ Maurice Philip Remy: The Gurlitt case: The true story of Germany's greatest art scandal. , Europa Verlag 2017, ISBN 978-3958901858 .

- ↑ a b Rule of Law Expressionism . Der Spiegel, November 18, 2013

- ↑ "Not a chance find". Reinhard Nemetz in an interview with Heribert Prantl. Süddeutsche Zeitung of November 22, 2013

- ↑ Stefan Koldehoff , Tobias Timm : They are finally back! , Die Zeit , No. 46, November 7, 2013

- ↑ Ingeborg Ruthe: Henchmen of the Nazis , Frankfurter Rundschau, November 4, 2013

- ↑ Breakdown series Too many questions remain unanswered ( Memento from November 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) br.de, November 20, 2013, accessed November 20, 2013

- ↑ a b Daniel Boese: Sensational find. Press conference ( Memento from November 5, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), art - Das Kunstmagazin , November 5, 2013

- ^ Sensational art treasure in Munich. Focus , November 3, 2013, accessed November 3, 2013 .

- ↑ a b Peter Dittmar: How Picassos ended up in a trashed apartment. Die Welt , November 3, 2013, accessed November 4, 2013 .

- ↑ a b Julia Voss : Münchner Kunstfund: Where is the rule of law? Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , November 17, 2013, accessed on November 17, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c Volker Rieble : Schwabinger Kunstfund: Politische Strafjustiz. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, November 25, 2013, accessed on November 25, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c Stephanie Lahrtz: Münchner Kunstfund: Return all paintings to Gurlitt? Neue Zürcher Zeitung , November 25, 2013, accessed on November 28, 2013 .

- ↑ Interview: Art expert demands return of all pictures to Gurlitt. In: Augsburger Allgemeine , December 4, 2013, accessed December 6, 2013.

- ^ Louise Barnett: Art dealer paid Nazis just 4,000 Swiss Francs for masterpieces , Daily Telegraph , November 10, 2013, accessed November 11, 2013

- ↑ Alexander Ikrat: Munich art in Kornwestheim? , stuttgarter-nachrichten.de, November 10, 2013, accessed on November 11, 2013

- ↑ Joint press release of the Bavarian State Ministry of Justice, the Bavarian State Ministry for Education and Culture, Science and Art, the Federal Ministry of Finance and the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media , accessed on November 12, 2013

- ^ The federal government and Bavaria publish suspicious works . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , November 11, 2013.

- ^ Münchner Kunstschatz: Authorities publish suspicious works from Gurlitt's fund , Spiegel Online from November 11, 2013

- ↑ Tim Ackermann: A new lead in the Gurlitt case leads to Dresden. Die Welt, November 12, 2013, accessed November 13, 2013 .

- ↑ sueddeutsche.de: Authorities publish the first pictures on the Internet

- ↑ FAZ.net: 590 pictures are published

- ↑ The press is entitled to the list of Gurlitt pictures ( memento from January 31, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), wdr.de, accessed on February 3, 2014

- ↑ Stefan Dege: The Gurlitt Task Force is leaving - questions remain. Deutsche Welle, January 14, 2016, accessed January 15, 2016 .

- ↑ Christiane Habermalz: Task Force: It remains at five stolen art works. Deutschlandfunk, January 14, 2016, accessed on January 15, 2016 .

- ↑ Nicola Kuhn: The meager balance of the Gurlitt task force. Die Zeit, January 14, 2016, accessed on January 15, 2016 .

- ↑ Lucas Elmenhorst: Comments on the suggestion of a "Lex Gurlitt". Handelsblatt, January 9, 2014, accessed on January 29, 2014 .

- ^ Corinna Budras: Law initiative on looted art: Lex Gurlitt in the Federal Council - The Gurlitt case. In: FAZ. January 14, 2014, accessed March 7, 2014 .

- ↑ New law after the Gurlitt case ( Memento from January 8, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), www.br.de, accessed on January 8, 2014

- ↑ The Washington Post: Art collector in German find: works in Austria too ( Memento from February 11, 2014 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ dpa: Art find: Gurlitt hoarded 60 other valuable pictures. In: Zeit Online. February 11, 2014, accessed February 11, 2014 .

- ↑ https://www.fr.de/kultur/kunst/gurlitt-hortete-noch-mehr-bilder-11256274.html

- ↑ a b gurlitt.info press release of March 26, 2014 ( memento of April 1, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on March 27, 2014

- ↑ a b Gurlitt wants to return pictures. Süddeutsche.de , March 26, 2014, accessed on March 26, 2014 .

- ^ To the Salzburger Kunstfund handelsblatt.com

- ↑ https://www.justiz.bayern.de/presse-und-medien/pressemitteilungen/archiv/2014/47.php

- ^ Testament of Cornelius Gurlitt. The Gurlitt Collection is to go abroad , süddeutsche.de from May 6, 2014.

- ↑ Gurlitt Collection comes to Bern: "Like a bolt from the blue". In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . May 7, 2014, accessed May 7, 2014 .

- ^ Deceased collector: Gurlitt's pictures go to the Kunstmuseum Bern. In: Spiegel Online. May 7, 2014, accessed May 7, 2014 .

- ↑ Gurlitt's legacy puts the art museum in trouble. bernerzeitung.ch, May 8, 2014, accessed May 8, 2014.

- ↑ Stefan Koldehoff: Art Legacy: Who Will Be Heir to Gurlitt? In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , May 11, 2014.

- ↑ Michael Sontheimer: Gurlitt Collection in Switzerland: Taskforce "Ahnungslos". At Spiegel Online , November 24, 2014 (accessed November 25, 2014).

- ↑ Julia Voss and Niklas Maak: Gurlitt case - no ifs or buts: Bern accepts the inheritance. faz.net, November 24, 2014 (accessed November 25, 2014).

- ↑ dpa: Gurlitt's pictures go to Bern. In: FAZ.net . December 15, 2016, accessed October 13, 2018 .

- ↑ Gurlitt is already regarded as the “figurehead” for Bern , Der Bund, January 15, 2018

- ↑ Reinhard Birkenstock : What rights does Cornelius Gurlitt have? Die Welt , November 17, 2013, accessed November 28, 2013 .

- ↑ Heinrich Wefing : Curse of the treasure. Die Zeit , November 21, 2013, accessed on November 28, 2013 .

- ↑ Carl-Heinz Heuer: The property law problem of "degenerate" art. Free University of Berlin , archived from the original on December 2, 2013 ; Retrieved November 25, 2013 .

- ↑ Act No. 59. Restitution of identifiable property to victims of the National Socialist repression of May 12, 1949. In: Ordinance Gazette for the British Zone. Hamburg. May 28, 1949. No. 26. pp. 152-165.

- ↑ The Gurlitt case and its consequences. Why is everything statute-barred so quickly? The legal historian Uwe Wesel in conversation with Stefan Koldehoff . In: Deutschlandfunk. Cultural issues. December 1, 2013. Accessed December 9, 2013.

- ↑ Maurice Philip Remy: The Gurlitt case. The real story of Germany's biggest art scandal. Europa Verlag, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-95890-185-8 , expropriation, p. 228-237, 602 .

- ^ Jürgen Lillteicher: The restitution of Jewish property in West Germany after the Second World War. A study of the experience of persecution, the rule of law and politics of the past 1945-1971 . Dissertation. Freiburg 2002. Available online: urn: nbn: de: bsz: 25-opus-21837 (pdf, 3.18 MB) [1]

- ^ Paul Ingendaay: Historical commission before from: The memory of the SPD is to be abolished. In an open letter, the historian Christina Morina addresses the SPD board. He wants to abolish his historical commission. Numerous scientists have joined the call. In: FAZ. August 6, 2018, accessed December 30, 2018 .

- ↑ Barbara Vogel (ed.): Restitution of Nazi looted art. The historically justified claim to a legal position. Eat. 2016

- ↑ Uwe Wesel: Art theft debate: Augsburger Landrecht. Is Cornelius Gurlitt a victim of justice? According to valid allied law, the son of the Nazi art dealer is without a doubt the owner of his paintings. All refund requests are no longer effective. In: Zeit Online. February 13, 2014, accessed December 30, 2018 .

- ^ Nephew of the Bonn gallery owner and founder of the Remagener Kulturbahnhof Rolandseck Johannes Wasmuth

- ↑ Johannes Wasmuth: Access to works of art under Nazi rule. In: Journal for Open Property Issues (ZOV) No. 2. 2015. pp. 98–113

- ^ Felix Bayer (dpa): Nazi looted art. Germany reaffirms its obligation to provide information. Spiegel Online, November 26, 2018, accessed December 30, 2018 .

- ↑ Stuart E. Eisenenztat: Imperfect Justice: Looted Assets, Slave Labor, and the Unfinished Business of World War II. Washington, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7867-5105-1 .; Stuart E. Eisenstat: Imperfect Justice. The dispute over compensation for victims of forced labor and expropriations. Munich, 2003. ISBN 3-570-00680-8

- ↑ as a result of the Military Government Act No. 52 of May 1945: Thorsten Kurtz: The Supreme Restitution Court in Herford. An investigation into the history, establishment and establishment of an international court of appeal in Germany. Berlin, Boston 2014. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-3-11-031663-6

- ↑ Maurice Philip Remy: The Gurlitt case. The real story of Germany's biggest art scandal. Europa Verlag, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-95890-185-8 , pp. 231 .

- ^ Carola Thielecke: Searching for traces - Nazi looted property research in libraries and archives information on the legal situation. Searching for traces - Nazi looted property research in libraries and archives. A further training offer from practice for practice. In cooperation with the Jewish Museum Berlin December 10th / 11th, 2015 in Berlin. Initiative advanced training for scientific special libraries and related institutions, December 28, 2015, p. 5 , accessed on January 1, 2018 .

- ↑ According to Section 30 of the Federal Restitution Act , claims in the event of innocent failure to meet deadlines (April 1, 1958) and reinstatement in the previous status in accordance with Section 169 of the Federal Compensation Act was possible until December 31, 1969

- ↑ except: loss of property due to sale

- ↑ on the proceedings between 1952 and 1957: Jürgen Lillteicher: Limits of Restitution. The restitution of Jewish property in West Germany after the Second World War. Lecture for the conference “Provenance Research for Practice. Research and documentation of provenances in libraries ”on September 11th and 12th in Weimar. Initiative advanced training for scientific special libraries and related institutions eV, 2015, pp. 6–8 , accessed on January 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Maurice Philip Remy: The Gurlitt case. The real story of Germany's biggest art scandal. Europa Verlag, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-95890-185-8 , pp. 232 .

- ^ Carola Thielecke: Searching for traces - Nazi looted property research in libraries and archives information on the legal situation. Searching for traces - Nazi looted property research in libraries and archives. A further training offer from practice for practice. In cooperation with the Jewish Museum Berlin December 10th / 11th, 2015 in Berlin. Initiative advanced training for scientific special libraries and related institutions, December 28, 2015, p. 8 , accessed on January 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Principles of the Washington Conference in relation to works of art that were confiscated by the National Socialists (Washington Principles). In: Foundation German Center for the Loss of Cultural Property. Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media, accessed on January 3, 2019 .

- ↑ Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. BUREAU OF EUROPEAN AND EURASIAN AFFAIRS / DECEMBER 3, 1998, December 3, 1998, accessed on June 10, 2019 .

- ↑ Joint statement of December 14, 1999, accessed on March 28, 2009: [2]

- ↑ Maurice Philip Remy: The Gurlitt case. The real story of Germany's biggest art scandal. Europa Verlag, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-95890-185-8 , pp. 236 .

- ↑ Prime Minister of the Czech Republic: THERESIENSTÄDTER DECLARATION June 30, 2009. Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media, June 30, 2009, pp. 6–7 , accessed on January 4, 2019 .

- ↑ JOINT DECLARATION on the implementation of the Washington Principles of 1998 between the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Department Head for Culture and Communication in the Federal Foreign Office and the advisor to the US State Department for Holocaust Affairs and the Special Envoy for State Department Holocaust Affairs. Berlin, Germany November 26, 2018. Federal Government, November 26, 2018, accessed on January 4, 2019 .

- ^ Foundation German Center for the Loss of Cultural Property. The Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media, January 1, 2015, accessed on January 3, 2019 .

- ↑ Previously unknown masterpieces by Dix and Chagall discovered. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , November 5, 2013, accessed on November 5, 2013 .

- ↑ a b The picture of Dix has long been known . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , November 7, 2013.

- ^ Nazi looted art: 1,500 works of art were in homes for decades. Bayerischer Rundfunk: B5 aktuell, November 3, 2013, archived from the original on November 6, 2013 ; Retrieved November 3, 2013 .

- ↑ Schwabinger Kunstfund: A denial, further reports, sober estimates . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . November 22, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ Retirees hoarded 1500 stolen masterpieces. Der Tagesspiegel , November 3, 2013, accessed on November 3, 2013 .

- ^ Symposium Art & Law: Gurlitt - what now? uni-regensburg.de

- ↑ a b Henning Kahmann: "Gurlitt - What now? Considerations of a lawyer". Art Chronicle, July 2016, accessed April 3, 2017 .

- ↑ Vanessa-Maria Voigt: Art dealers and collectors of the modern age under National Socialism. The Sprengel Collection 1934 to 1945. Reimer, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-496-01369-3 , pp. 138-139, with details.

- ^ Munich art discovery is a "political problem of the federal government". In: Deutschlandradio , November 8, 2013, accessed on November 9, 2013.

- ↑ a b Gurlitt's list. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, November 6, 2013, accessed on November 6, 2013 .

- ^ Allies confiscated Gurlitt works after the end of the war In: Süddeutsche Zeitung. November 5, 2013, accessed November 5, 2013.

- ↑ German watercolors, drawings and prints [1905-1955]. A midcentury review, with loans from German museums and galleries and from the collection Dr. H. Gurlitt. American Federation of Arts, New York 1956.

- ^ Art find: Allies had confiscated works after the war. Courier , November 6, 2013, accessed November 6, 2013 .

- ↑ Münchner Kunstschatz: Gurlitt does not want to voluntarily return a single picture , spiegel.de, November 17, 2013, accessed on November 17, 2013

- ^ German at Center of Looted-Art Case Is Said to Consider Restitution Claims , accessed January 28, 2014

- ↑ Gurlitt's lawyers demand the return of the pictures , accessed on February 22, 2014

- ^ Hans Henning Kunze: Restitution "Degenerate Art": Property Law and International Private Law. de Gruyter, Berlin 2000, p. 46.

- ^ Max Beckmann , Lempertz.com, accessed November 4, 2013

- ↑ a b Ira Mazzoni : The Reclaimer and His Son (with a photo of Beckmann's lion tamer from the auction house catalog). Süddeutsche.de , November 3, 2013, accessed on November 3, 2013 .

- ↑ Who do the expensive works of art belong to? In: The time . November 4, 2013, accessed November 4, 2013.

- ↑ Gurlitt case: Flechtheim heirs offer help to Gurlitt's task force , spiegel.de, November 22, 2013, accessed on November 23, 2013

- ↑ Thomas E. Schmidt: August Macke from Gurlitt estate auctioned off at Grisebach , zeit.de, November 30, 2013, accessed on December 13, 2013

- ↑ The art messie hid these works in his apartment . In: Focus , November 5, 2013.

- ↑ In pictures: Long-lost art unveiled in Germany . In: BBC News , November 5, 2013.

- ^ Matthias Thibaut: The long way to Spitzweg , zeit.de, November 29, 2013, accessed on November 29, 2013

- ↑ Fabienne Riklin and Julia Stephan: Schweizer gave Gurlitt pictures by Picasso and Chagall , schweizamsonntag.ch, November 9, 2013, accessed on November 11, 2013

- ↑ Hildebrand Gurlitt: Allied Interrogation June 1945 , accessed on November 11, 2013

- ↑ Chagall belonged to a Jewish family , stuttgarter-nachrichten.de, December 11, 2013, accessed on December 17, 2012

- ↑ Munich art find of exceptional quality. Little clarity about ownership structure , Neue Zürcher Zeitung of November 6, 2013

- ↑ Strauss-Kahn's ex-wife demands painting back , welt.de, November 8, 2013, accessed on November 8, 2013

- ↑ a b Nazi looted art back with a Jewish family. Tages-Anzeiger , May 15, 2015.

- ↑ 1500 lost works of art discovered in an apartment , Süddeutsche Zeitung , November 3, 2013

- ↑ Meike Hoffmann's speech at the conference on March 3rd / 4th. September 2013 in Berlin, in the original via video, [3]

- ↑ Most important art find of the post-war period. n24.de, November 4, 2013, accessed November 4, 2013

- ↑ Münchener Kunstfund is “political problem of the federal government” in Deutschlandradio , November 8, 2013, accessed on November 9, 2012

- ↑ www.lootedartcommission.com , see also English Wikipedia

- ↑ Harriet Alexander, Louise Barnett, Nick Squires: Art experts demand Germany releases list of € 1bn Nazi art trove. In: The Telegraph . November 4, 2013, accessed November 4, 2013

- ^ A case of mass robbery. In: Jüdische Allgemeine . November 4, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013

- ^ Jewish Claims Conference involved in Gurlitt Task Force in: Der Spiegel , November 18, 2013, accessed November 19, 2013.

- ^ Julia Voss: Gurlitt database: The precedent. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, November 13, 2013, accessed on November 13, 2013 .

- ↑ Daniel Kothenschulte : The lost honor of Cornelius Gurlitt. In: The world . November 19, 2013. Retrieved November 19, 2013 .

- ↑ Eberhard W. Kornfeld : Der Münchner Kunstfund: Eine Medienhysterie. Neue Zürcher Zeitung , November 23, 2013, accessed on November 28, 2013 .

- ↑ Johannes Wasmuth: Standpunkt: The exhibition "Inventory Gurlitt" in the Bundeskunsthalle served sensationalism. A comment and a warning about state injustice. General-Anzeiger Bonn, March 20, 2018, accessed on December 28, 2018 .

- ↑ Handout for the implementation of the "Declaration of the Federal Government, the Länder and the Municipal Central Associations on the Finding and Returning of Cultural Property Stolen by National Socialist Persecution, especially from Jewish Property" from December 1999 from February 2001 revised in November 2007. Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and Media , May 2013, p. 27 , accessed on December 28, 2018 .

- ^ Michael Sontheimer: Final report of the Gurlitt task force: Label fraud. In: Der Spiegel. January 16, 2016, accessed December 28, 2018 .

- ↑ Jens Bisky, Catrin Lorch, Jörg Häntzschel: Non-final report . Süddeutsche Zeitung, January 15, 2016