Restitution of looted art

Restitution of art looted from the National Socialist era is the attempted restoration of ownership of works of art that were stolen during the Nazi era by returning or compensating them to the former owners or their heirs. The term looted art refers to a "loss caused by persecution" that primarily affected Jews and those who were persecuted as Jews, whether within the then German Reich from 1933 to 1945 or in one of the areas occupied by the Wehrmacht during World War II .

In a statement to the House Banking Committee in Washington in February 2000, taking into account the problem of specific figures, it was assumed that around 600,000 works of art were stolen, expropriated, confiscated or robbed by Germans between 1933 and 1945: 200,000 within Germany and Austria, 100,000 in Western Europe and 300,000 in Eastern Europe. At the end of the Second World War, the Allied occupying powers found a large number of stolen works of art, secured them and returned them to the respective countries of origin. Nevertheless, many works of art of unclear origin ended up in the international art trade and in public collections. The number of works of art that have not been returned to their rightful owners and may still be identifiable and are believed to be in public collections and private collections scattered around the world is estimated at up to 10,000.

With the so-called Washington Declaration , 44 states agreed to a non-binding international regulation in 1998, according to which these states undertake to ensure that looted art is found and returned. Since then, well over a thousand paintings and art objects from around 20 countries have been restituted to the owners or their heirs.

expression

The term restitution goes back to the Latin verb "restituere", which can be translated as "to restore". It has been anchored in international law since the 19th century with the principle of the inviolability of private property in armed conflicts.

In the legal field, it means the restoration of a legal situation (here the right to property ) that has been disturbed by injustice under international law. The return of the stolen property ( restitutio in integrum ) is the simplest form of restoring legal peace . Subsequent to this is exchange for something of equal value ( restitution in kind ), originally physical, in practice often with money, or compensation for the loss if restoration is impossible. In the context of cultural assets, restitution refers to the return of, for example, illegally exported and traded cultural assets, and in the case of Nazi-looted art, the return of cultural assets confiscated as a result of persecution.

Post-war restitutions

At the end of the Second World War, the Allied occupying powers found themselves in a difficult situation with regard to the stolen art and cultural assets:

- Most of the paintings that were stolen or bought from those persecuted within the Reich were privately owned, often in the collections of Nazi leaders or regional officials. Some works ended up in museum collections, others were sold through the international art trade. In all cases, however, their origin was not clearly documented and their whereabouts were often unknown.

- Some of the works of art stolen from the occupied territories were also found in private collections, particularly in the collections of the National Socialist elite. A large part was stored in almost 1,500 depots, some of which were well documented. Larger holdings were also taken over from public collections and museums or moved through the art trade, particularly in Switzerland. Since the full extent of the robbery is not known, most of it must be considered lost, especially the art treasures from Eastern Europe.

- During the war, many public and some private collections were evacuated to protect them from bomb damage. These camps were often identical to the depots for looted art, resulting in a difficult-to-understand mixture of actual property and looted art both from their own country and from the occupied countries.

- The extensive collections of the museums in Danzig, Breslau and Berlin as well as the Prussian State Library represent a legal and political peculiarity, which were evacuated to Eastern Pomerania and Lower Silesia during the course of the war . When the former German territory east of the Oder-Neisse line fell under Soviet and Polish administration after the Potsdam Agreement of August 2, 1945 , these extensive depots, in which an unknown quantity of looted art was also stored, came into Polish sovereign territory.

The problems of restitution were exacerbated from the start by the Cold War and the demarcation between East and West. The 5 million cultural objects found in the 1,500 depots in Germany and Austria were divided into 2.5 million in the American-occupied zone , 2 million in the Soviet zone and 500,000 objects in the other areas. Between 1945 and 1950 the Americans and British restituted 2.5 million cultural objects. From 1944 to 1947, the Soviets transferred 1.8 million cultural objects from the zone they occupied to their own country, of which they returned between 1955 and 1958 around 1.5 to 1.6 million objects to the GDR and other Warsaw Pact states. Individual holdings were exchanged between the Eastern and Western powers, for example works of art stored in Thuringia that came from France and art treasures from Poland found in Baden-Württemberg. However, since all of these bundles were mixed with objects from different origins, it was often difficult to trace the ownership structure. The stock of German property that has remained in Russia is the subject of numerous disputes under international law and is often seen as a synonym for "looted art".

Internal and external restitution

Most of the works of art found were in Bavaria and thus in the American-occupied zone . So it was the Americans who shaped the principles of restitution. What was found was first collected and pre-sorted in so-called "Collecting Points". The local conditions resulted in the most important collection point for looted art, the “ Central Collecting Point ”, being built in the former administration building of the NSDAP and in the Führerbau on Königsplatz in Munich . Here, works of art were brought in from around 600 storage depots in the three western zones, centrally recorded and registered, their origin and ownership determined as far as possible and then restituted. The works of art that were intended for the “ Fuhrer Museum ” in Linz and works from the Hermann Göring collection also flowed into this inventory . From August 1945 to May 1951, the Munich Collecting Point was able to publish 250,000 of the works of art found. A total of 463,000 paintings were returned during this period. In the case of internal restitution , i.e. returns within Germany, the main concern was the repatriation of the actual property to the museums, insofar as this could be distinguished from looted art. With external restitution , works of art were returned to the countries from which they had been stolen. It was restituted exclusively to states in trust ; Private individuals could not register any claims. After that, it was up to the respective administrations to return the works to the former owners or to decide on further handling. In many cases, the governments of the states included the works of art in their own collections, regardless of their origin, and in some cases sold them in later years. This has resulted in very different country-specific problems and legal situations to this day.

legal development

The damaging, destroying and robbing of cultural assets in war, which has always been practiced in armed conflicts, was first outlawed by the Hague Convention on Land Warfare (HLKO) of 1907. The HLKO is a comprehensive international legal agreement between the signatory states. German warfare in World War II clearly showed the limited effect of international law. The Allies emphasized in the London Declaration of January 5, 1943 that on the basis of the ban on looting contained in Article 56 HKLO "every transfer and sale of property [...] will be declared null and void". The mutual restitution claims of the states were based on this regulation.

The theft of the property of Jews and those persecuted as Jews was defined as a crime against humanity in the sense of international law by the IMT statute (London Charter of the International Military Tribunal) of 1945. The systematic nature of the National Socialist art robbery aimed not only at physical destruction but also at ethnic and cultural destruction and was to be replaced by its own order. "The inner attitude of the perpetrator (mens rea), who strives for the extermination of another ethnic group in both physical and cultural terms, forms the link between physical destruction and the confiscation of property and assets, which in itself is not otherwise to be regarded as reprehensible . […] For this reason, the confiscation of works of art belonging to a member of an ethnic group, which is to be destroyed as a whole, is to be considered a crime against humanity.”

As a rule, private individuals had no direct and immediate claim against a state on the basis of international law. The restitution legislation therefore finds its place in the regulations of public law claims, i.e. those of a claimant against the state, as well as in the design of the civil law foundations, i.e. the legal relationship of citizens against each other or against legal persons.

Allied Laws

After the war, so-called nullity laws were passed in France, the Netherlands, Austria and other countries, which – in accordance with the London Declaration of 1943 – fundamentally regulated that legal transactions affecting groups of people persecuted during the occupation period were ineffective. In the three West German occupation zones, on the other hand, no general ineffectiveness regulation was pronounced. The German administrative bureaucracy, in particular the financial authorities with the same staff, argued that property losses during persecution and expropriation due to laws and regulations had formal legal validity and had been concluded with legal effect. Contrary to this attitude, the basis of the legal restitution rules were created by the Western Allies.

The American Military Government Act No. 59 of November 10, 1947 comprehensively regulated the restitution of property confiscated for racial, religious and political reasons and shaped legal principles that are still used today, for example in the implementation of the Washington Declaration . They are based on the preceding legal assumption that every legal transaction made by a persecuted person after January 30, 1933 is a persecution-related loss of assets, and thus contained a reversal of the civil-law rule on the burden of proof . After the cut-off date (September 15, 1935 - date of the Nuremberg Laws), all legal transactions could in principle be contested, since the seller could be assumed to be in a predicament. In public law, i.e. vis-à-vis the state, applications for compensation could be made. For this purpose, a registration period of twelve months from the entry into force of the law applied in the western allied zones. It was mainly used for immovable assets, but many injured parties could not make use of it because of its short, limited time. The regulations were largely meaningless for the restitution of works of art, since it was rarely known where the paintings and other works were located. There were no equivalent refund rules in the Soviet zone; there were only a few returns at the instigation of those affected.

In cases of "loss of property through sale" , it applies that robbery is not only to be understood as taking away , but also giving away , since under the pressure of persecution, through discriminatory tax levies, professional bans and confiscation of assets, people were forced to give up their belongings sell to finance subsistence or emigration under the steadily deteriorating conditions. In the case of a dispute, the new owner of a property previously owned by Jews had to prove

- that a reasonable purchase price, corresponding to the market value, was agreed,

- that the purchase price had been freely disposed of by the seller being prosecuted

- and in the event that the legal transaction was concluded after September 15, 1935, the promulgation of the Nuremberg Race Laws : that it would also have come about without the rule of National Socialism.

These procedural principles took into account the fact that those persecuted by the National Socialists had generally lost all relevant evidence during their persecution.

The application of Radbruch's formula

During their rule, the National Socialists legitimized the confiscation and expropriation, the "loss of property through state-sovereign action" with a variety of legal ordinances and regulations . Numerous laws were repealed by the Allied Control Council between 1945 and 1947, including Control Council Law No. 1 of September 20, 1945: the Reich Citizenship Law, the decree on the registration of Jewish assets, the law on the restoration of professional civil service, the law on admission to the bar and some others. But the mere repeal of the law was not sufficient in many cases. In the legal-theoretical debate, the legal philosopher Gustav Radbruch coined the thesis in 1946 that between positive law and justice , a decision should always be made against the law and in favor of material justice if and only if the law in question was either "unbearably unjust" is to be viewed or the law "consciously denies" the fundamental equality of all people inherent in the concept of law from the perspective of the interpreter. From this so-called Radbruch formula , three classification schemes have been developed for the legal validity of the National Socialist laws:

- The first group includes laws that must be applied even if they are unjust: This applies to the laws that were repealed after 1945 but remain in force for the period of their existence.

- The second group are "intolerably" unjust laws: They must give way to justice, so they are declared void retrospectively .

- In the third case, laws are named that do not even aim to be just. These laws are not rights. They are presented as if they never existed.

Regarding the restitution of stolen Jewish property, it was significant that certain laws were declared null and void. But it was not until February 14, 1968 that the Federal Constitutional Court ruled that the contradiction to justice had reached such an unbearable level with the "Eleventh Decree to the Reich Citizenship Law of November 25, 1941" that it had to be regarded as void from the start. Thus, at least in the case law, the confiscation of the belongings of the persecuted on the occasion of the deportations was condemned as unbearably unjust.

No restitution of "degenerate" art

Of the 20,000 works of art that were confiscated in 1937 as part of the "Degenerate Art" campaign, the majority were previously owned by the museums concerned and thus belonged to the "public sector". The law on the confiscation of products of degenerate art (confiscation law) passed in 1938 was not repealed by the Control Council, but existed until 1968 and only became invalid after it was not included in the collection of the Federal Law Gazette. The legal reasoning for maintaining the existing status was that the German Reich was the owner of the works of art and could also sell them in accordance with the property rights; the sales transactions thus retained their validity. In September 1948, the Monuments and Museums Council of Northwest Germany followed this view and, in order to maintain legal peace, decided not to make any reclaims. However, most of the confiscated works of art are considered lost, a prominent example being Franz Marc's The Tower of the Blue Horses .

However, the assessment of the privately owned paintings that were confiscated as "degenerate art" in 1937, such as the 13 paintings by the art historian Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers , which she had entrusted to the Hanover Provincial Museum as a loan, or the collection of the widow Frieda Doering, is different , which was donated to the City Art Museum in Szczecin . After the war, Frieda Döring's heirs sued for return or compensation on the basis of the Allied restitution order. The lawsuit was dismissed by the restitution courts in 1965 and 1967, since the ruling at the time was of the opinion that the expropriation of the paintings without compensation was not an injustice to be judged according to the principles of restitution for loss caused by persecution, since the collector herself had not been persecuted. The confiscation of the works of art belonging to Frieda Döring was the result of a general ideological campaign by the Nazi regime and had no direct connection with her person.

In the legal discourse of the following years, this view was questioned and many lawyers proposed the application of Radbruch's formula and the declaration of the nullity of the confiscation law, since this law established a political and ideological defamation campaign aimed at the psychological destruction of the artists.

In the proceedings of the heir Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers against the Lenbachhaus in Munich for the publication of the painting by Paul Klee Sumpflegende , this view was confirmed. With the decision of December 8, 1993, the Munich Regional Court ruled that the confiscation law is to be regarded as void, at least for works of art originating from private ownership. The lawsuit was nevertheless dismissed and the painting not restituted as the court ruled that the absolute statute of limitations of thirty years had expired, despite the fact that Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers could not leave the Soviet Union.

Laws of the Federal Republic of Germany

In 1952, with the Transition Agreement , the Allies placed responsibility for restitution under the stipulation that the Federal Republic of Germany undertook to provide effective compensation to those who had been persecuted for racial, political or religious reasons. As part of the resulting reparation policy , a number of laws were enacted dealing with the restitution of property and compensation for those persecuted:

- With the Luxembourg Agreement of 1952, the Federal Republic undertook to create compensation laws and to pay a total of DM 3.5 billion as global restitution for persecution, slave labor and stolen Jewish property to Israel and the Jewish Claims Conference (JCC). These funds were to be used, among other things, to integrate the destitute, mainly Eastern European Jews who had emigrated to Israel .

- The Federal Supplementary Law on Compensation for Victims of National Socialist Persecution (BergG) of 1953 provided for compensation for loss of life, body and health, freedom, property and assets. It also received the tax damages suffered during the Nazi era, e.g. B. through the Reich flight tax or the Jewish property tax. German nationals who had to be resident in West Germany were eligible to apply.

- The Federal Compensation Act (BEG) of 1956 expanded the group of people who were regarded as victims of persecution and included other facts, but still excluded claims from people resident abroad. Russian prisoners of war , forced labourers , communists , Roma , Yeniche , euthanasia victims , forced sterilized , “ asocial ” and homosexuals were not taken into account.

- With the Federal Restitution Act (BRüG) of 1957, the Federal Republic of Germany undertook to pay damages for confiscated and no longer locatable assets, provided that these items had entered the territory of the Federal Republic of Germany. It thus expressly included the restitution of property that had been stolen in Western and Eastern Europe if it could be proven that the stolen property had been taken to West Germany. The deadline for filing claims under this law was March 31, 1959.

- The BEG final law of 1965 was expressly intended to restore "national honor" and draw a "dignified line". It contained numerous improvements, extensions of deadlines and exceptions for cases of hardship. Finally, it was determined that no more applications could be submitted after December 31, 1969.

In the GDR almost no refunds took place, since according to the historiography of the time "the fascist takeover of power was caused by the monopoly capitalists and the working class was abused" and can now not be held accountable. Accordingly, there was no legal regulation.

statute of limitations on claims

Both the Allied measures and the restitutions made by the Federal Republic of Germany in the 1950s and 1960s are considered inadequate, particularly with regard to the Nazi looting of cultural assets. In practice, only a few works of art were restituted "inside" in the post-war period. The reimbursement laws, with their tight deadlines, fell short. Also, only a few of the former owners still lived in Germany. Many had been murdered, the survivors emigrated, families torn apart. The problem was also that the whereabouts of many works of art were not known - and often are not known to this day. Intransigence, a lack of guilt and the unwillingness of the new owner to return the stolen property also played a not inconsiderable role.

This becomes particularly clear in the case of the widow Elisabeth Gotthilf, whose painting by Leopold von Kalckreuth "The Three Ages" was "disposed of" as Jewish removal goods when her apartment in Vienna was confiscated in March 1938. In 1941, the picture of unknown provenance came to the Bavarian State Painting Collections and was stored there first because of the war and later because of a lack of exhibition space. After the war, Elisabeth Gotthilf searched unsuccessfully for her lost painting; it was only in 1970 that the family was able to locate it in Munich. Your request for return was denied with the notice that all deadlines for filing the claim had expired.

From the end of the 1960s, efforts were made to draw a line under the topic, as was clearly expressed in the BEG final law. At the latest after the thirty-year statute of limitations according to the Civil Code , the restitution of Jewish property was considered a closed topic.

The restitutions after 1990

The situation changed with German reunification in 1990. In the public discussion, which grew out of the demand for the restitution of socialized property, a new debate arose about the theft of the property of the persecuted and murdered under National Socialism, which had previously received little attention. On September 29, 1990, the GDR parliament, which still existed, passed the property law with the aim of reversing property losses since 1945. Under pressure from Jewish organizations, this law was amended so that property lost for racial, political, religious or ideological reasons between 1933 and 1945 was also to be included in the restitution. This was intended to fulfill the reparation obligations of the Allied restitution law assumed by Germany in the context of the two-plus-four negotiations in September 1990.

The Road to the Washington Declaration

When it became known that insurance deposits and stolen gold from formerly Jewish property were being deposited in Swiss banks, the discussion at the international level became even more explosive. When on January 1, 1998, two paintings by Egon Schiele , both on loan from the Leopold Museum in Vienna, were confiscated on behalf of the heirs of former Jewish owners at a major retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) New York , this steered the public Attention to the issue of the incomplete restitution of art looted by the Nazis.

The first affected painting, Schiele 's Tote Stadt III from 1911, came from the collection of Viennese cabaret artist Fritz Grünbaum , who died of tuberculosis in the Dachau concentration camp . The sister of his wife, who was also murdered, probably took the picture with her when she fled to Switzerland in 1938 and sold it there. Through other sales outlets, it came into the possession of the Viennese art collector Rudolf Leopold in 1960, after whose donation it has been part of the museum's inventory since 2001. Before the end of the exhibition, Fritz Grünbaum's heirs living in the USA had demanded that it be returned in accordance with American law. In May 1998, the confiscation order was lifted because the picture had come to New York under "safe conduct" under the Arts and Cultural Affairs Law and it had to be returned accordingly. Since then it has been back in Vienna.

The second painting is Egon Schiele’s “ Portrait of Valerie Neuziel ” (“Wally”) from 1912. It belonged to the private collection of the Viennese gallery owner Lea Bondi-Jaray from 1925 until it was “Aryanized” in 1938. Her request for return was not granted before her death in 1968. Her heirs applied for the artwork to be released during the exhibition at MoMA. As in the Grünberg case, the confiscation was overturned in May 1998 under the Arts and Cultural Affairs Law, but it remained in court custody under the National Stolen Property Act. An out-of-court settlement was reached in July 2010. The painting was returned to the heirs by the Leopold Museum Private Foundation and returned to the collection in exchange for a payment of 19 million dollars to the heirs.

These spectacular processes with cross-border effects sensitized the international art world, both museums and the art trade. More than 50 years after the end of the war, it became clear that the problem of Nazi-looted art had not been solved and that there was a considerable need for action. In December 1998, at the Washington Conference on Holocaust-Era Assets, attended by 44 states, 12 non-governmental organizations, particularly Jewish victims' associations, and the Vatican, the so-called “ Washington Declaration ”. The final statement was received with applause by the participants. It seeks to locate works of art that were confiscated during the National Socialist era, find the rightful owners or their heirs, and take the necessary steps quickly to find fair and just solutions.

The declaration contains neither a legally binding obligation nor does it justify individual restitution claims by those affected, but it does represent a general regulation that was shaped by legal regulations in many of the participating countries and led to considerable consequences and sensational restitutions.

measures in Germany

With the Washington Declaration , Germany has also committed itself to checking state museum holdings for cultural assets confiscated as a result of Nazi persecution and returning found works of art to their rightful owners. On December 14, 1999, a "joint declaration by the federal government, the states and the central municipal organizations on the tracing and return of cultural property confiscated as a result of Nazi persecution, especially from Jewish property" (joint declaration) was issued. However, no individual, enforceable claim for return can be derived from this, as it existed or exists in the allied reimbursement laws, the BRüG, the BEG and the Assets Act. Rather, the museums should be given guidelines on how to handle and deal with art that is suspected of being looted by the Nazis. In practice, this means that requests for return are examined on the basis of Allied legislation and that deadlines that have already expired can be disregarded. This is a voluntary, moral commitment, not a binding legal regulation. It applies to public institutions; This legal formation does not apply to private collections, art dealers and auction houses, even if some private institutions have expressly declared their adherence to the Washington Principles. In recent years there have been some efforts to exclude the objection of the statute of limitations in certain cases in the Civil Code , in order to be able to successfully assert claims against Jewish owners for works of art confiscated as a result of persecution.

provenance research

Provenance research in particular , i.e. research into the history and origin of a work of art, subsequently became a labour-intensive central research field in museum work, because all works of art created before 1945 and purchased or taken over after 1933 can theoretically come from looted art inventories. To support this almost unmanageable task, the federal and state governments in Magdeburg have set up the coordination office for cultural property losses as a central public institution . The main task of this office is to collect search and find reports of cultural assets. Using the communication possibilities of the Internet, the Internet database “Lost Art Register”, which is freely accessible worldwide, was set up for this purpose in 2000. This is where international reports of searches and finds of cultural assets confiscated as a result of Nazi persecution as well as other items taken away in connection with the Second World War are documented. The aim of the coordination office's work is to identify the actual owners in order to support the research mandate for the public collections. The coordination office does not have the task of carrying out independent provenance research or of influencing restitution negotiations.

A balance sheet in October 2008 showed that up to this point in time 6,630 objects from 70 institutions had been reported as possibly found looted art. By the same date, around 4,000 artworks had been entered as "wanted".

On March 28, 2007, the Culture Committee of the Bundestag held a hearing on the subject of the return of Nazi-looted art with lawyers, historians and museum representatives. It became clear that the required intensification of provenance research would require greater financial resources. During the hearing, some experts suggested establishing a central contact point at the German Museums Association, where funding can be requested and where the research results come together. In 2008, this office for provenance research at the Institute for Museum Research of the National Museums in Berlin - Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation began its work. It has the task of providing museums, libraries, archives and other publicly maintained institutions in the Federal Republic of Germany with the preservation of cultural property with material support in provenance research. A budget of one million euros per year was made available for this purpose, which was increased to two million euros in 2012.

At present, there is an increasing willingness on the part of museums to face up to their own historical responsibility and initiate provenance research on their own initiative. The provenance research of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation in Berlin, the Hamburger Kunsthalle and the Bavarian State Painting Collections is described as exemplary . Positions have been established in these museums and filled with art historians dedicated solely to researching the provenance of museum exhibits.

Another institution set up after the Washington Declaration is the Advisory Commission in connection with the return of cultural property confiscated as a result of Nazi persecution. especially from Jewish ownership , also called the Limbach Commission . It was set up on July 14, 2003 under the direction of the Magdeburg coordination office and serves to clarify disputes in return matters.

provenance documentation

Since January 1, 2006, the Federal Office for Central Services and Unresolved Property Issues (BADV) has been systematically examining the remainder of the "Central Collecting Point Munich" again. This portfolio, which was handed over to a trust company of the Foreign Office in May 1952 , is now part of the departmental assets of the Federal Finance Administration. In May 2008, it contained around 2,300 paintings, graphics, sculptures, handicrafts and an additional 10,000 coins and books. By the 1960s, most of these had been placed on permanent loan in about a hundred museums. Success is hoped to come from more accessible sources than were available to post-war provenance researchers, as well as from the opportunities offered by the Internet. A selection of previous research results has been published in one of the “Provenance Documentation” databases. It is primarily intended to illustrate "the seriousness of the efforts of the German state in the field of redress for National Socialist injustice". By May 2008, the return of 36 researched works was planned or had already taken place.

After researching Nazi-looted items in the Nuremberg city collections, the provenance of some books, paintings and graphics could be clarified and it was determined or suspected that they were confiscated as a result of Nazi persecution. The objects are listed on the homepage of the city archives and can therefore be viewed by the public.

return cases

In December 2008, a symposium convened to mark the 10th anniversary of the Washington Declaration took stock. After that, it was possible that the topic was given greater importance both publicly and in the professional world, but measured in terms of the scope, there were few results in the search for and return of Nazi-looted art. Since many cases are negotiated and closed privately, the coordination office in Magdeburg cannot give any specific figures.

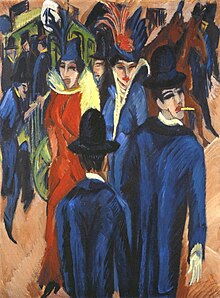

In public, it is the spectacular cases that determine the topic. An outstanding example is the return of the painting by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, now referred to as Causa Kirchner: Berlin street scene . In August 2006 it was announced that the Berlin Senate would return the painting to the heiress of the former Jewish owner, in accordance with the Washington Declaration. The case triggered heated discussions and legal disputes and made it clear, both in politics and in the media, the existing legal uncertainty that the legally non-binding but morally binding principles can trigger.

362 paintings, graphics, handicrafts, books and musical instruments were returned in 2019 thanks to the work of the research association Provenance Research Bavaria (FPB).

Looting of cultural property in public libraries

While the return of works of art attracts a comparatively large amount of public attention, little is known about other state-organized thefts of other cultural assets. However, the Washington Agreement affects cultural assets in a broader sense. In many German libraries these illegal acquisitions are being researched more or less intensively. For example, the Berlin City Library still contains large quantities of books from formerly Jewish property. A receipt for 45,000 Reichsmarks from 1943 provided the first clue. The city library had thus bought 45,000 books from the city pawn shop, which came from the homes of deported Jews. In an exchange of letters between the pawn shop, the city treasurer and the library management, it was argued that the books could not be given to the library free of charge because the proceeds from the sale were intended to serve "all purposes connected with solving the Jewish question" (i.e. mass murder finance the victims). The acquisition of the individual books can be traced in part in the acquisition books of the city library, in which each acquired volume is usually listed with its title and accession number. Below that there is a reference volume J 1944-1945 with 1,920 listed titles, the J stands for Jewish books .

Restitution as an international problem

The fact that the problem of the works of art to be restituted is not limited to Germany is evident from the large number of countries that were occupied and plundered by the Germans in World War II. The sale of the looted art via Switzerland before and during the Second World War ensured that it was distributed worldwide. Decades of disregard for the problem, including by the art trade, has also promoted the worldwide distribution of works that were once owned by Jews. After the signing of the Washington Declaration by 44 states, recognizing the international problem and with a common goal, the handling and legal implementation in the individual countries is still very different. Since 1998, around a thousand works of art worldwide have been returned to the heirs of their former owners or restored through compensation payments based on the Declaration.

Austria

In contrast to Germany, a nullity law was passed in Austria on May 15, 1945, which declared legal transactions during the German occupation to be null and void if they were “carried out in the course of political or economic penetration by the German Reich”. According to this, previous owners could have demanded the return of assets without being bound by a deadline if they had been lost due to political, racial or economic persecution. As a result, however, this broad legal regulation was specified by 1949 with seven restitution laws, partially restricted and given deadlines. By 1956, ownership of 13,000 works of art could be clarified. The actual return to the many former owners who had emigrated was prevented by the rigid export ban law of 1918. A large number of works of art from well-known collections remained in Austrian museums. An example of the mentioned problems that arose from the external restitution is the decision of the Advisory Board under the Austrian Art Restitution Act of 2012 on a painting by Eduard von Grützner . The German Federal Office for External Restitutions handed this over to the Austrian state in 1958, which ultimately left it to the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere . It was not until 2012 that the advisory board recommended restituting the work to the heirs of the previous owner.

The confiscation of the Schiele paintings Wally and Tote Stadt III in New York on January 1, 1998 brought the problem into public discussion and scandalized Austria's "refusal to return" practice. Taking this into account, the federal law on the return of works of art from Austrian federal museums and collections was passed on December 4, 1998 . It created an acknowledgment that a "second expropriation" was taking place through the export prohibition laws. As a result, there were much acclaimed releases, such as 224 works of art to the heirs of Louis Rothschild in February 1999, on the recommendation of the Art Restitution Advisory Board , or the five paintings by Gustav Klimt to the heiress of the Bloch-Bauer family, Maria Altmann , in May 2006 after a long lawsuit. But the hesitant provenance research and restitution practice is still criticized, especially by the Jewish community in Vienna .

France

As an Allied power and co-signatory, France had already declared the London Agreement of January 5, 1943 to be national law in November 1943, thereby annulling any transfer of property during the National Socialist occupation. In 1944, a commission was set up to repatriate the stolen cultural assets. By 1950, 45,000 of the 61,000 works of art stolen and then confiscated could be restituted to the owners or their heirs. Of the remaining 16,000, 2,000 were given to various national museums under the inventory designation "Musées Nationaux Récupération" (MNR). Approximately 12,500 works rated as less valuable were sold in the following years; the remainder were allocated to an artists' support fund.

At the beginning of the 1990s, the MNR holdings in public collections became a problem because they were all Nazi-looted items and the museums had never bothered to find the rightful owners. In September 1999, the "CIVS" was founded, the Commission for the Compensation of Victims who had been harmed by looting under anti-Semitic laws during the occupation. By 2005, 15,000 applications had been made, of which around 200 related to the loss of works of art. Compensation was paid in 64 cases, 22 were rejected. The return of works of art was ordered in four cases.

Netherlands

After the war, the problem of looted art received little attention in the Netherlands. Most of the returned works of art from the Collecting Points between 1946 and 1948 ended up in public museums without any research being carried out into their origins, so Fritz Mannheimer ’s collection went to the Rijksmuseum and the international art trade . It was not until the 1990s that a change in thinking began, when Jacques Goudstikker 's heirs demanded clarification about the gallery holdings that had been believed lost and it became known that many of the paintings were on display in the Dutch collections. In 1997 an investigative commission was set up to examine the Dutch museum holdings. In March 1998, the institutions themselves founded the "1940-1948 Museum Acquisitions Project" to research the provenances. In 2001, this work gave rise to the “Advisory Commission on Restitution Applications for Cultural Objects from the Second World War – Instituut Collectie Nederland” (ICN). Their tasks consisted of provenance research, determining the loss process and deciding on return applications. A deadline of April 4, 2007 was set for requests for restitution, after which no more requests should be made.

By 2005, this commission had made twenty-one recommendations for the return of 200 art objects. In the Goudstikker case, 200 paintings found were returned to the heirs, and another 500 have been identified in museums and private collections around the world, but particularly in Germany. The Dutch state bought back four old master paintings, and the heiress gave him a fifth as a thank you for the provenance work.

See also

web links

- Special exhibition Good Business. Art trade in Berlin 1933-1945. April to July 2011, Active Museum in the New Synagogue Berlin , accessed May 18, 2020

- Special exhibition Robbery and Restitution. Jewish-owned cultural assets from 1933 to the present day. 2008/2009 at the Jewish Museum Berlin and the Jewish Museum Frankfurt am Main , accessed December 4, 2010

- Lost Art Register of the German Lost Art Foundation Magdeburg, retrieved on April 23, 2018

- Implementation of the Federal Restitution Act (BRüG) / research for works of art at the Federal Office for Central Services and open property issues

- “Special order Linz” – Zeit.de

- CCP database (original index cards) in the German Historical Museum

- International Research Portal for Records Related to Nazi-Era Cultural Property

- Veit Probst : Lecture "The digitization of historical auction catalogues: A new source base for provenance research and restitution processes" on YouTube

literature

- Thomas Armbruster: Restitution of Nazi booty, the search, salvage and restitution of cultural assets by the Western Allies after World War II. Zurich, de Gruyter, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-89949-542-3 . ( Writings on the protection of cultural assets ) (Also: Zurich, University, dissertation, 2007).

- Inka Bertz, Michael Dorrmann (ed.): Looted art and restitution. Jewish-owned cultural assets from 1933 to the present day. Published on behalf of the Jewish Museum Berlin and the Jewish Museum Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-8353-0361-4 , (exhibition catalog for an exhibition of the same name in 2008/2009 at the Jewish Museum Berlin and the Jewish Museum Frankfurt) .

- Thomas Buomberger: Looted art-art robbery. Switzerland and the trade in stolen cultural assets at the time of the Second World War. Orell Füssli, Zurich 1998, ISBN 3-280-02807-8 .

- Uwe Fleckner (ed.): Attack on the avant-garde. Art and art policy in National Socialism. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-05-004062-2 , ( writings of the research center "Degenerate Art" 1).

- Constantin Goschler, Philipp Ther (ed.): Looted art and restitution. "Aryanization" and Restitution of Jewish Property in Europe . Fischer Paperback Publishing House, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-596-15738-2 .

- Ulf Häder: Contributions by public institutions in the Federal Republic of Germany on dealing with cultural assets from former Jewish possession. Coordination office for loss of cultural property, Magdeburg 2001, ISBN 3-00-008868-7 , ( Publications of the coordination office for loss of cultural property 1).

- Hannes Hartung: Art theft in war and persecution. The restitution of looted and looted art in conflict of laws and international law. de Gruyter, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-89949-210-2 , ( writings on the protection of cultural assets ), (also: Zurich, Univ., Diss., 2004).

- Stefan Koldehoff: The pictures are with us. The business of Nazi-looted art. 1st edition. Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-8218-5844-9 .

- Jörn Kreuzer, Susanne Küther from the Institute for the History of German Jews : "Second-hand Nazi loot" - provenance research in the library of the IGdJ , in: Brintzinger et al. (Ed.): Libraries: We open worlds , Münster 2015, ISBN 978-3-95925-000-9 , pp. 238-248; Digital copy (PDF; 14 MB)

- Susanne Küther Institute for the History of the German Jews : Everything kosher? - NS looted property research in a Jewish special library , lecture text on the occasion of the event Search for Traces - NS looted property research in libraries and archives on 10./11. December 2015, "Initiative advanced training for scientific special libraries and related institutions eV" digital copy (PDF; 1.1 MB)

- Hanns Christian Löhr: The brown house of art, Hitler and the "special order Linz". Visions, crimes, losses. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-05-004156-0 .

- Hanns Christian Löhr: The iron collector. The Hermann Goering collection. Art and Corruption in the “Third Reich”. Man, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-7861-2601-0 .

- Melissa Müller , Monika Tatzkow: Lost Pictures, Lost Lives - Jewish Collectors and What Became of Their Works of Art. Elisabeth-Sandmann-Verlag, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-938045-30-5 .

- Jonathan Petropoulos: Art theft and collecting mania. Art and Politics in the Third Reich. Propylaea, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-549-05594-3 .

- Andrea FG Raschèr : Restitution of cultural assets: bases for claims - obstacles to restitution - development. In: KUR – Art and Law , Volume 11, Issue 3–4 (2009) p. 122. doi : 10.15542/KUR/2009/3-4/13

- Alexandra Reininghaus: Recollecting. Robbery and Restitution. Passagen-Verlag, Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-85165-887-3 .

- Gunnar Schnabel, Monika Tatzkow: Nazi Looted Art. Manual art restitution worldwide. Proprietas Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-00-019368-2 .

- Julius H. Schoeps , Anna-Dorothea Ludewig (eds.): A debate without end? Looted art and restitution in German-speaking countries . Publisher for Berlin-Brandenburg, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-86650-641-1 .

- Birgit Schwarz: Hitler's Museum. The photo albums “Picture Gallery Linz”. Documents for the "Führer Museum". Böhlau, Vienna and others 2004, ISBN 3-205-77054-4 .

- Birgit Schwarz: genius mania. Hitler and art. Böhlau, Vienna and others 2009, ISBN 978-3-205-78307-7 .

- Katharina Stengel (ed.): Before the annihilation. The state expropriation of Jews under National Socialism. Campus-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main and others 2007, ISBN 978-3-593-38371-2 , ( Scientific Series of the Fritz Bauer Institute 15).

itemizations

- ↑ Hannes Hartung: Art theft in war and persecution. The restitution of looted and looted art in conflict of laws and international law. Zurich 2004, p. 60 f.

- ↑ Jonathan Petropoulos in testimony before the United States House Committee on Financial Services in Washington on February 10, 2000 ( memento of October 17, 2012 at the Internet Archive ), retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ↑ Hannes Hartung: Art theft in war and persecution. The restitution of looted and looted art in conflict of laws and international law. Zurich 2004, p. 44 f.

- ↑ Herrick, Feinstein: Resolved Stolen Art Claims, 2009 , accessed April 18, 2020.

- ↑ Erich Kaufmann: The international law bases and limits of restitution. AöR 1949, p. 13 f.; quoted here from Hannes Hartung: Art theft in war and persecution. The restitution of looted and looted art in conflict of laws and international law. Zurich 2004, p. 66.

- ↑ Hannes Hartung: Art theft in war and persecution. The restitution of looted and looted art in conflict of laws and international law. Zurich 2004, p. 28.

- ↑ Gunnar Schnabel, Monika Tatzkow: Nazi Looted Art. Handbook. Art restitution worldwide. Berlin 2007, p. 164.

- ↑ Jonathan Petropoulos in testimony before the United States House Committee on Financial Services in Washington on February 10, 2000 ( memento of October 17, 2012 at the Internet Archive ), retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ↑ Iris Lauterbach : The Central Art Collecting Point in Munich. In: Inka Bertz, Michael Dorrmann (ed.): Looted art and restitution. Jewish-owned cultural assets from 1933 to the present . Frankfurt a. M. 2008, p. 197.

- ^ Joint Allied London Declaration of 5 January 1943, paragraph 3; quoted here from Wilfried Fiedler : The Allied (London) Declaration of 5 January 1943: Content, Interpretation and Legal Nature in Post-War Discussion . available from the Legal Archives of the University of Saarland [1] , accessed on March 27, 2009

- ↑ Hannes Hartung: The restitution of looted art in Europe. In: Julius Schoeps, Anna-Dorothea Ludewig (eds.): A debate without end? Looted art and restitution in German-speaking countries . Berlin 2007, p. 178 fn. 6

- ↑ Gunnar Schnabel, Monika Tatzkow: Nazi Looted Art. Handbook. Art restitution worldwide. Berlin 2007, p. 102 f.

- ↑ Jost von Trott zu Solz : Art restitution on the basis of the resolutions of the Washington Conference of 1998 and the joint declaration of 1999. In: Julius Schoeps , Anna-Dorothea Ludewig (ed.): A debate without end? Looted art and restitution in German-speaking countries . Berlin 2007, p. 191.

- ↑ BVerfGE 23, 98 of February 14, 1968

- ↑ Collection of the Federal Law Gazette, Part III, December 31, 1968; See Hans Henning Kunze: Restitution of degenerate art, property law and international private law. Berlin 2000, p. 261 f.

- ↑ Gunnar Schnabel, Monika Tatzkow: Nazi Looted Art. Handbook. Art restitution worldwide. Berlin 2007, p. 365.

- ↑ Hans Henning Kunze: Restitution of degenerate art, property law and international private law. Berlin 2000, p. 262. de Gruyter Verlag, ISBN 978-3-11-016818-1 (writings on the protection of cultural assets / Cultural Property Studies).

- ↑ Judgment LG Munich of December 8, 1993 in IPRax 1995, p. 43; see also: Gunnar Schnabel, Monika Tatzkow: Nazi Looted Art. Handbuch. Art restitution worldwide. Berlin 2007, p. 289 f.

- ↑ Constantin Goschler: Two waves of restitution. The return of Jewish property after 1945 and 1990. In: Inka Bertz, Michael Dorrmann (eds.): Looted art and restitution. Jewish-owned cultural assets from 1933 to the present . Frankfurt a. M. 2008, p. 30.

- ↑ Ilse von zur Mühlen: Leopold von Kalckreuth's triptych The three ages - The case of Elisabeth Gotthilf. In: Coordination Office for the Loss of Cultural Assets (ed.): Contributions by public institutions in the Federal Republic of Germany to dealing with cultural assets from former Jewish possession . Magdeburg 2001, p. 244 ff.

- ↑ Dan Diner: Restitution. About the search of property for its owner. In: Inka Bertz, Michael Dorrmann (ed.): Looted art and restitution. Jewish-owned cultural assets from 1933 to the present . Frankfurt a. M. 2008, p. 21 f.

- ↑ Peter Raue: Summum ius summa iniuria - stolen Jewish cultural property put to the test by the lawyer. In: Your own story. Provenance research in German museums in an international comparison. Publications of the Coordination Office for the Loss of Cultural Assets, Magdeburg 2002, p. 288 f.

- ↑ Gunnar Schnabel, Monika Tatzkow: Nazi Looted Art. Handbook. Art restitution worldwide. Berlin 2007, p. 393.

- ↑ Chronology: The "Wally case". In: The Standard. 21 July 2010, retrieved 27 February 2011

- ↑ Washington Declaration of December 3, 1998 accessed April 26, 2020

- ↑ Gunnar Schnabel, Monika Tatzkow: Nazi Looted Art. Handbook. Art restitution worldwide. Berlin 2007, p. 193.

- ↑ Joint Statement of December 14, 1999, retrieved March 28, 2009: [2]

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Dillmann: More legal certainty. September 12, 2018, retrieved June 24, 2019 .

- ↑ Bundesrat Drucksache 2/14: Draft of a law to exclude the statute of limitations for claims for the return of lost items, in particular in the case of cultural property confiscated during the Nazi era (cultural property return law - KRG) . January 7, 2014 ( bundesrat.de [PDF; retrieved June 24, 2019]).

- ↑ Lost Art Register, Magdeburg: Lostart: Coordination Office for the Loss of Cultural Assets in Magdeburg , retrieved on May 8, 2009

- ↑ Interview with Dr. Michael Franz: The facts are difficult to reconstruct. In: Badische Zeitung October 10, 2008, documented at: — ( Memento of April 26, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), retrieved March 23, 2009

- ↑ Job site home page: [3] , retrieved January 22, 2014

- ↑ Commissioner for Culture and Media ( Memento of April 14, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), bundesregierung.de, retrieved on April 15, 2013

- ↑ Federal Office for Central Services and Unresolved Property Questions, Provenance Research: — ( Memento of April 12, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) – retrieved on March 28, 2009

- ↑ Object List

- ^ "Taking responsibility" organized by the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation and the Coordination Office for the Loss of Cultural Assets, Berlin, December 12, 2008

- ↑ Monika Tatzkow, Gunnar Schnabel: Press release and report on the return of the painting by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner: "Berliner Straßenszene" — ( Memento of August 20, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), retrieved on March 28, 2009

- ↑ Bavarian provenance research association publishes 2019 activity report

- ↑ Fokke Joel: Books of the Murdered. An exhibition in Berlin shows the books that were stolen from Jewish households during National Socialism. Finding the works was detective work. In: Die Zeit No. 5/2009; about the exhibition in Berlin January/February 2009:

- ↑ Art Law Group, Herrick, Feinstein LLP: Resolved Stolen Art Claims ( memento of 2 April 2016 at the Internet Archive ), retrieved 27 February 2011

- ↑ Gunnar Schnabel, Monika Tatzkow: Nazi Looted Art. Handbook. Art restitution worldwide. Berlin 2007, p. 127 ff.

- ↑ Resolution of the Art Advisory Board ( Memento of February 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Gunnar Schnabel, Monika Tatzkow: Nazi Looted Art. Handbook. Art restitution worldwide. Berlin 2007, p. 140 f.

- ↑ Gunnar Schnabel, Monika Tatzkow: Nazi Looted Art. Handbook. Art restitution worldwide. Berlin 2007, p. 144 ff.

- ↑ Pieter den Hollander, Melissa Müller: Jacques Goudstikker (1897–1940), Amsterdam. In: Melissa Müller, Monika Tatzkow: Lost images, lost lives. Jewish collectors and what became of their artworks , Munich 2009, p. 229.