Nuremberg laws

With the Nuremberg Laws - also known as the Nuremberg Race Laws or Aryan Laws - the National Socialists institutionalized their anti-Semitic and racist ideology on a legal basis. They were accepted unanimously at the 7th Reich Party Congress of the NSDAP , the so-called “Reich Party Rally of Freedom”, in the early evening (5.45 pm) of September 15, 1935 by the Reichstag , which had been convened by telegram to Nuremberg for this purpose . They included

- the law for the protection of German blood and German honor ( RGBl. I p. 1146) - the so-called blood protection law - and

- the Reich Citizenship Law (RGBl. I p. 1146).

- In addition to these two “race laws”, the Imperial Flag Act (RGBl. I, p. 1145) is now often included under the collective term “Nuremberg Laws”, although it was not counted among them at the time.

All three laws were promulgated in the Reich Law Gazette Part I No. 100 on September 16, 1935 with the addition “at the Reich Party Rally of Freedom”. They were repealed by the Allied Control Council Act No. 1 of September 20, 1945.

"Blood Protection Act"

The law for the protection of German blood and German honor , passed on September 15, 1935, prohibited marriage and extramarital sex between Jews and non-Jews . It was supposed to serve the so-called “keeping the German blood clean”, a central component of the National Socialist racial ideology . Violations of the law were referred to as " racial disgrace " and threatened with prison and penitentiary (exclusively for male participants) - regardless of which party was Jewish.

This determination was often personally attributed to Adolf Hitler . It testifies to his image of women , according to which women are sexually immature. A supplementary ordinance dated February 16, 1940, requested by Hitler, according to which the woman should remain exempt from punishment despite the accusation of favoritism, points in this direction. The lawyers Wilhelm Stuckart and Hans Globke provide a purely practical justification in their legal commentary from 1936: The statement of the woman involved is usually required for the transfer, and the woman is no longer entitled to refuse to provide information if released from punishment .

Section 3 of the law, which only came into force on January 1, 1936, prohibited Jews from employing “ German-blooded ” maids under 45 years of age. Behind this was the ideological assumption that “the Jew” would otherwise attack them.

Shortly after the race laws were passed, a First Ordinance on the Blood Protection Act on November 14, 1935 (RGBl. I p. 1334 f.) Stipulated that “ Jewish mixed race with two Jewish grandparents” would only be “German-blooded” or “Jewish Mixed race with a Jewish grandparent “were allowed to marry. Corresponding applications were mostly unsuccessful; after 1942 they were no longer accepted “for the duration of the war”. Marriages between two “quarter Jews” should not be concluded. “Quarter Jews” and “Germans with blood”, on the other hand, were allowed to marry. Behind this was the racist paradigm of preserving “German and related blood”. A section 6 of the First Ordinance extended the ban on marriage to other groups: as a matter of principle, all marriages that endangered the “keeping of German blood” should be avoided. A circular listed " Gypsies , Negroes and their bastards ".

Section 4 of the law forbade Jews to hoist the Reich and national flags or to display the colors of the Reich. The threat of punishment was imprisonment for up to a year. However, Jews were allowed to "show the Jewish colors".

As early as February 1935, the Gestapo had forbidden Jews to use the swastika flag, without a legal basis at that time; A corresponding decree of the Reich Ministry of the Interior followed in April . Allegedly this was supposed to prevent the attempt by Jewish companies to camouflage themselves with flags and to pass themselves off as "Aryan".

German-Japanese marriages represented a special case, due to possible diplomatic entanglements with the Japanese alliance partner. These were undesirable and were often prevented by German authorities despite the lack of a legal basis. For this purpose, according to research by the historian Harumi Shidehara Furuya, intensive investigations were carried out in each individual case on the background of those affected - in particular on the diplomatic relevance. In Japan, the diplomatic missions abroad tried to give the outside impression that the Japanese were “honorary Aryans” and described the term “Aryans” as “perhaps not scientifically flawless”. In practical terms, "he simply means: Gentile". Internally, however, the German embassy in Tokyo pointed out in February 1939 that “a basic regulation must be made”, whereby “Japanese racial pride and sensitivity” must be spared. In September 1940 Hitler himself took the view that “it would be more correct, in the interests of keeping the German race pure, not to allow such marriages in the future, even if there were reasons for foreign policy in favor of such marriages”. However, the head of the Reich Chancellery, Hans Heinrich Lammers , convinced him to "postpone all similar applications for at least 1 year through dilatory treatment from now on, in order to then turn to rejections." Hitler agreed to this proposal.

Reich Citizenship Law

The Reich Citizenship Law created different classes of citizens.

According to this law, only the “Reich citizen” should have full political rights (Section 2, Paragraph 3 of the Reich Citizenship Act - RBG). This person must - initially - be a citizen of "German or related blood" and prove through his behavior that he is "willing and able to serve the German people and the Reich faithfully." 2 RBG).

In this way, a three-way division was legally prepared:

- "Reich Citizens" (§ 2 RBG), who are only allowed to do so under the "provisions of the law" (§ 2 Paragraph 3 RBG)

- "Citizens" (with reference to the Reich and Citizenship Act of 1913, but which the state "is particularly obliged to do" (Section 1, Paragraph 1, Clause 2 RBG)) and

- ultimately those who could not meet either of the two criteria.

The intended “Reich Citizenship Letters” (Section 2 (2) RBG) were not awarded until the end of the Second World War: he would even have the “German” as a citizen per se in those “which prove through his behavior that he is willing and is suitable to serve the German people and the Reich in loyalty "(§ 2, Paragraph 1, Clause 2 RBG), who could have become" citizens of the Reich "and thus" sole bearers of full political rights "(§ 2, Paragraph 3 of the RBG) are - and those who could not or did not want to achieve this - “have to classify”.

The “three-way division” stipulated by this law was practically only used against those who are not “German or related blood”: Section 3 of the Reich Citizenship Act made possible any - legal-formal - administrative regulation for the interpretation of this law with reference to persons who are not “ citizens of German or related blood”.

So was z. For example, the assimilated “ Jewish half-breeds ” were only granted the right to vote and “provisional citizenship”. As a result of the Reich Citizenship Law, no Jew was allowed to hold a public office any more, by ordinance . The Jewish civil servants , who had previously been spared dismissal due to the so-called front fighter privilege in the 1933 Law for the Restoration of the Civil Service , had to resign on December 31, 1935. In addition, Jews lost the right to vote in politics . Further ordinances to the Reich Citizenship Act in 1938 withdrew their license from Jewish doctors and lawyers (4th ordinance on the RBG of July 25, 1938 and 5th ordinance on the RBG of November 30, 1938). Finally, the 11th ordinance on the Reich Citizenship Act of November 25, 1941, initiated by Hitler, became significant. German Jews were thus deprived of their citizenship if they took up residence abroad. In Deportation lost Jews crossing the border of their nationality, also went all their property and assets , including its claims under life and annuity formally to the State.

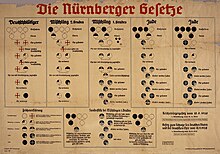

classification

The First Ordinance on the Reich Citizenship Act of November 14, 1935 defined who could remain citizens of the Reich as a “Jewish half-race” and who would be excluded as “Jew”:

- People with at least three Jewish grandparents were considered (full) "Jews".

- People with one Jewish parent or two Jewish grandparents were considered a “first-degree hybrid”.

- People with a Jewish grandparent part were classified as a "second degree half-breed".

"Mixed race first degree" who belonged to the Jewish religious community or were married to a Jew were classified as "Jews". The term “ valid Jew ” came up for them later . All other " half-Jews " and "quarter Jews" were officially referred to as " Jewish mixed race ".

Exceptions

In Section 7 of the First Ordinance on the Reich Citizenship Law , Hitler personally reserved the right to approve exceptions: “The Fuehrer and Reich Chancellor can grant exemptions from the provisions of the implementing ordinances”. The often abbreviated quote “I decide who is a Jew with me!” Is attributed to Hermann Göring , but it does not match the facts.

Of more than 10,000 requests for improvement that were checked and filtered by several lower courts, only a few were successful. The participation of the petitioners in the world war and political services to the "movement", their "racial appearance" and their character assessment were essential criteria. “Full Jews” were only favored in two cases. By the year 1941, 260 "half-breeds of the first degree" had achieved their equality with a "German-blooded" ("Certificate of classification within the meaning of the first ordinance to the Reich Citizenship Act of November 14, 1935"). In 1,300 cases, petitioners were reclassified from “valid Jews” to “Jewish mixed race”.

According to a decree of the High Command of the Wehrmacht on April 8, 1940, the "first degree half-breeds" and the " Jewish Versippten " (the "German-blooded" spouses in so-called mixed marriages ) were to be released from the Wehrmacht . Exceptions were only possible with Hitler's personal approval until 1942, but were still tolerated in exceptional cases. In June 1944 the "second degree half-breeds" were also to be excluded from service in the Wehrmacht. With the tacit support of their superiors, some of these soldiers, who had been declared unworthy of defense, remained in the Wehrmacht. After the assassination attempt on July 20, 1944 , Hitler revoked his special permits for officers who were considered to be "first degree half-breeds"; at the same time, all of the officers with “Jewish infiltration” were dismissed at the end of 1944. In reality, individual soldiers who had been issued with a “German Blood Declaration” at an early stage continued to serve until the end of the war.

Members of the NSDAP , teams and subordinates of the SS as well as farmers within the meaning of the Reichserbhofgesetz were subject to even stricter criteria. They had to produce a large ancestral passport vulgo large Aryan proof, which showed a consistently "German-blooded" family tree up to the reference year 1800. The cut-off year 1750 was valid for SS leaders.

The Encyclopedia of National Socialism speaks of an "appointment as an honorary Aryan" and refers to the exception clause in Section 7 of the First Ordinance on the Reich Citizenship Act , which does not, however, use this term. Beate Meyer only uses the word "Ehrenarian" in quotation marks and casually for exceptional cases in which "deserving companions" with a Jewish background approached the party chancellery and Hitler directly and achieved an improvement in status without a formal process. Steiner / Cornberg point out that the term “honorary Aryan” did not officially exist and that it was only used colloquially .

Use of the trade and imperial flags

The Reichsflaggengesetz (Reichsflaggengesetz) declared the swastika flag to be the Reichsflagge and authorized the Reich Minister of the Interior to issue further implementing provisions. The fact that Jews were prohibited from using the Reich flag was not stipulated in the Reich Flag Act, but in the "Blood Protection Act".

In the following "Ordinance on the flagging of ships" of January 17, 1936 (RGBl. I p. 15), however, it is pointed out that the Reich Minister of Transport, in agreement with the Reich Minister of the Interior and the Deputy Leader, merchant ships whose owners are under the Provisions of Section 4 of the Blood Protection Act fall, which may prohibit the flying of the trade flag.

Come about

The seventh Reich Party Congress took place in Nuremberg from September 10 to 16, 1935. He was originally supposed to emphasize the introduction of conscription and the exemption from the restrictive provisions of the Versailles Treaty . Hence the title “Reich Party Rally of Freedom”.

On September 12th, the third day of the party congress, Reichsärzteführer Gerhard Wagner gave a speech in which he surprisingly announced that the National Socialist state would shortly prevent the further mixing of Jews and “Aryans” through a “law for the protection of German blood” . Adolf Hitler extended the order and left immediately of the Reich Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick to Ministerialdirigenten Wilhelm Stuckart and the head of the "nationality Referates" in the Reich Interior Ministry, Bernhard Lösener , and work out other administrative staff draft legislation. Since some of them had to travel from Berlin, the working group could not be constituted until the evening of September 13th in Nuremberg. Because of the time pressure, the responsible ministers waived requirements and left it to the ministerial officials to draft bills.

Wagner, who stayed with Hitler constantly in Nuremberg, wanted to introduce a compulsory separation of “ mixed marriages” and a ban on marriage for quarter Jews as well, while the ministerial bureaucrats pointed out difficulties in practical implementation. Hitler himself finally opted for the milder bill; he was able to present himself as a moderate statesman who had his party under control, and he avoided foreseeable conflicts with the Catholic Church .

The essential contents of these Nuremberg Laws remained indefinite and could be further developed at will. In the Blood Protection Act, for example, until November 1935 it was unclear who was considered a Jew under the law. It also remained open in which cases a prison sentence or prison sentence could be recognized. The legal quality of “citizens” and “provisional citizenship” remained completely unformed.

Reactions

According to Gestapo reports , the Nuremberg Laws were "largely received with satisfaction, not least because psychologically, more than the unpleasant individual actions, it will bring about the desired isolation of Judaism". In Catholic circles, however, they would “find no approval; The only thing that is welcomed is that the Jewish legislation prevents excesses in anti-Semitic propaganda and excesses ”. It must remain open whether these statements were representative and whether this partial criticism was only due to caution, because these statements overheard by SD employees came from public discussions.

The declaration of the Reich Representation of Jews in Germany of September 24, 1935, published in the Jüdische Rundschau , among others , began with the words: “The laws passed by the Reichstag in Nuremberg have seriously affected the Jews in Germany. But they should create a level at which a tolerable relationship between the German and the Jewish people is possible. [...] The prerequisite for a tolerable relationship is the hope that the Jews and Jewish communities in Germany will be given the moral and economic possibility of existence by ending their defamation and boycott. "

Representatives of the revisionist wing of the Zionists such as Georg Kareski (who, as chairman of the State Zionist Association, gave an interview to the attack - which was largely rejected), on the other hand, advocated a "complete separation of Jews and Aryans." Some Orthodox Jews welcomed the ban on "mixed marriage" . The "assimilants" in Germany are thus deprived of any basis. Other Jewish citizens believed that a permanent and legally regulated solution for living together had now been found. In doing so, they overlooked the fact that the Nuremberg Laws were only an empty framework. The fact that the notice deliberately gave the impression that these regulations apply “only full Jews” contributed to the reassurance; Hitler had previously deleted this note himself, but released the text for publication in the version of the draft.

Representatives of the industry in Nazi Germany had concerns about possible effects abroad. However, the feared sanctions were hardly noticeable. Since according to the law the "Jewish half-breeds" Rudi Ball (ice hockey) and Helene Mayer (fencing) were allowed to take part in the 1936 Summer and Winter Olympics held in the German Reich, and they were also perceived as Jews abroad , there were planned sanctions in connection with the Olympic Games (especially on the part of the USA) withdrawn from the ground.

The reports of the social democratic Sopade describe the Nuremberg Laws as exceptional political laws with a “sexual pathological character”, by which the Jews are assigned a position “outside of humanity”. The Führer is the "prisoner of his bandits" and has to give in to their terrorist demands.

Later episodes

Until the end of the National Socialist German Reich , the legal status of Jews was further restricted by a large number of other laws and ordinances , which affected almost all areas of public and private life.

After the Jewish star was introduced in occupied Poland in 1939 , Jews in the Reich had to wear it as of September 19, 1941. The male Jewish part of a "mixed marriage" was also obliged to wear the star if the marriage had remained childless.

The Jewish partners from mixed marriages as well as the “Jewish Versippten”, as the “German-blooded” husbands from mixed marriages were called, were obliged to do forced labor in the course of the war and were often barracked in camps of the Todt Organization . In Berlin, shortly before the end of the war, the “German-blooded” wives were appointed accordingly.

The plans mentioned in the minutes of the Wannsee Conference in 1942 and those discussed by speakers in two subsequent conferences were not implemented. Thereafter, the forced divorce of mixed marriages with subsequent deportation as well as the forced sterilization of Jewish mixed race were named as goals.

The three Nuremberg Laws were repealed by the Allied Control Council Law No. 1 of September 20, 1945.

Controversial interpretations

The question of whether the Nuremberg Laws were a spontaneous decision or whether a long-cherished plan was implemented was controversial among historians.

Most of the older specialist literature shows that the race laws came into being completely surprising and were passed spontaneously. This contradicts the fact that on July 26, 1935 registrars had already been instructed not to process bids for mixed marriages due to a pending new regulation. Even Hitler's thought games about a new citizenship law and memoranda of Hanns Kerrl and Roland Freisler on the marriage law can be proven as early as 1933. The unimplemented draft of a law "regulating the position of the Jews", which Rudolf Hess sent to Julius Streicher on April 6, 1933 , anticipates the provisions of the later "Blood Protection Act" in Section 15 and contains stricter regulations than the Reich Citizenship Act.

The historian A. Przyrembel describes the 37th session of the Criminal Law Commission as the "first significant brainstorming [...] which prepared the conception of the Nuremberg Laws and its implementation provisions in essential aspects", which in the summer of 1934 was attended by Roland Freisler and Fritz Grau as well as the later one Resistance fighter Hans von Dohnanyi took part in his capacity as advisor to the Nazi Reich Minister of Justice Franz Gürtner . At the meeting, he criticized the fact that the draft law worked out there “does not achieve the overarching goal of 'racial legislation' - namely the guarantee of fundamental 'racial protection'."

The extent to which demands from the party base and incidents such as the Kurfürstendamm riot of 1935 accelerated or even prompted the legal regulation is judged controversially . The “violence from below”, the “popular anger” staged by party branches, was used at least by individual influential National Socialists such as Reinhard Heydrich and Gerhard Wagner to demand stricter laws against Jews. Others feared a loss of trust among the population if the unleashed violence disrupted peace and order and the state's monopoly of force was undermined. According to Saul Friedländer , the Nuremberg Laws “should make it known to everyone that the party's role was anything but played out […] This would reassure the mass of party members, individual acts of violence against Jews would end through the establishment of clear 'legal' guidelines, and the political one Activism would be “directed towards well-defined goals”.

Lately the widespread representation of Lösener's in the specialist literature has been questioned, who describes Wilhelm Frick as disinterested and uninformed. Longerich refers to an entry in Goebbels' diary of September 14, 1935:

“Frick and Hess there too. Consult laws. New citizenship law ... Ban on Jewish marriages ... We are still working on it. But that is how it is decided. The cleaning will be received. "

The self-portrayal of the ministerial officials involved, who stylized their participation as a moderating influence or even resistance, is also controversial today. At least the alleged maximum demands, such as sterilization or treating “eighth Jews” like “full Jews”, cannot be proven in any of the six drafts found.

The thesis, published by non-specialist researchers since 2005, that the Committee for Legal Philosophy founded by Hans Frank had "played a major role" in the preparation of the Nuremberg Laws, aroused decided opposition and led to an international debate about "fake news" on this issue .

statistical data

The number of “religious Jews” is estimated at 505,000 to 525,000 in 1933, to which, according to the National Socialists' definition, a further 180,000 assimilated Jews should be added. Norbert Frei assumes 562,000 people who were considered Jews in 1935 according to the First Ordinance on the Reich Citizenship Law .

Yehuda Bauer gives for the National Socialist German Reich with Lutz Eugen Reutter and JDC documents as sources for 1933 499,682 listed Jews, 2,000 "three-quarter Jews", 210,000 "half-Jews" and 80,000 "quarter Jews", altogether 790,000 persecuted because of Jewish origin, so the historians I. Lorenz and J. Berkemann, who add: “The numbers are very unreliable.” After the Nazi invasion of Austria and the Sudetenland, the number increased accordingly. In Austria there were 185,246 Jews and at least 150,000 so-called mixed race. The movement of refugees from 1933 onwards reduced the Jewish population in Central Europe by 440,000 at the same time by 1939.

According to the 1939 census , there were 330,539 Jews (including 297,407 religious Jews), 71,126 “Jewish first-degree mixed race” (including 6,600 Mosaic Confession) and 41,454 “Jewish second-degree mixed race” according to the Nazi definition.

On April 1, 1943, officially only 31,910 Jews lived in the Greater German Reich . About half of them had to wear the yellow star; the Jewish partners in “non-privileged mixed marriages” were also obliged to do this .

According to the Reich Crime Statistics of 1937, 512 men were convicted of " racial disgrace ", 355 of them were Jews. Between 1936 and 1940 1,911 men were convicted of "racial disgrace". The evaluation of the judgments passed in Hamburg from 1936 to 1943 shows that Jewish men were punished much more severely than "Germans with blood". Around a third of the Jewish victims of justice received prison sentences of between two and four years; just under a quarter were punished even more severely. The maximum sentence was 15 years. In at least fifteen cases, the judges used legal devices to impose death sentences that were also carried out (e.g. against Leo Katzenberger and Werner Holländer ).

On June 23, 1950, the federal law on the recognition of free marriages of racially and politically persecuted persons ( Federal Law Gazette 1950 p. 226) granted the marriage status retrospectively to the civil partnerships that had been refused marriage due to the Nazi racial laws that one of the partners was no longer alive. By 1963 1,823 corresponding applications had been made, of which 1,255 were approved.

See also

- National Socialist Racial Hygiene

- Law on tenancy agreements with Jews

- Legal Advice Act

- Marriage Act (Germany) , Marriage Act (Austria)

- Die Unwertigen , documentary from 2009 by Renate Günther-Greene

literature

- Uwe Dietrich Adam: Jewish policy in the Third Reich. Droste, Düsseldorf 2003 (= unchanged reprint from 1972), ISBN 3-7700-4063-5 (history of the origins of the Nuremberg Laws).

- Cornelia Essner: The 'Nuremberg Laws' or The Administration of Rassenwahns 1933-1945. Schöning, Paderborn 2002, ISBN 3-506-72260-3 (also habilitation thesis at TU Berlin 2000, criticism of Lösener's self-portrayal and involvement of the state bureaucracy).

- Otto Dov Kulka: The Nuremberg race laws and the German population in the light of secret reports on the Nazi situation and mood. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 32 (1984), pp. 582–636 ( PDF ).

- Ian Kershaw : Hitler 1889-1936. DVA, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-421-05131-3 (in Chapter 13, especially p. 711, evidence of well-planned preparations).

- Volker Koop : I decide who is Jewish: “Honorary Aries” under National Socialism , Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2014, ISBN 978-3-412-22216-1 .

- Hans Mommsen : Auschwitz, July 17, 1942. The road to the European “final solution to the Jewish question” . dtv 30605, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-423-30605-X (detailed description in chapter 3).

- Jeremy Noakes: "Where do the 'mixed Jews' belong?" The emergence of the first implementing regulation for the Nuremberg Laws. In: Ursula Büttner et al. (Ed.): The Unlawful Regime ..., Volume 2: Persecution, Exile, A New Beginning With A Load. Christians, Hamburg 1986, ISBN 3-7672-0963-2 .

- Hans Robinsohn: Justice as political persecution. The jurisprudence in "racial disgrace" at the Hamburg Regional Court 1936–1943 . DVA, Stuttgart 1977, ISBN 3-421-01817-0 .

- John M. Steiner, Jobst F. von Cornberg: arbitrariness in arbitrariness. Liberation from the anti-Semitic Nuremberg laws. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 46 (1998), pp. 143–187 ( PDF ).

- James Q. Whitman: Hitler's American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law. Princeton University Press, 2017, ISBN 978-0-69117-242-2 .

Web links

- Eleventh ordinance to the Reich Citizenship Act of November 25, 1941

- The Nuremberg Laws ( LeMO )

- Reich Citizenship Law and Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor (“Nuremberg Laws”), September 15, 1935, and the first two implementing provisions, November 14, 1935 , in: 1000dokumente.de

- Display board "Reich Committee for Public Health"

- Collection of some anti-Jewish laws and ordinances in their original wording

- The Nazi Race Laws ("Nuremberg Laws")

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Blood Protection Act on Wikisource

- ↑ Meyers Lexikon , 8th edition, eighth volume, Sp. 525, Leipzig 1940: “Nuremberg Laws , Bez. For two significant laws of the nat.-soc. Reichs: Blood Protection Act and Reich Citizenship Act. "

- ↑ Lothar Gruchmann : "'Blood Protection Act' and Justice ...", in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 31 (1983), p. 441. ifz-muenchen PDF

- ↑ Stuckart-Globke: Comments on the German race legislation. Volume 1, Munich and Berlin 1936-1b, quoted on pp. 18/19.

- ^ Otto Palandt (editor): Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch , 2nd edition, CH Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung , Munich and Berlin 1939, p. 1202.

- ^ First Ordinance (Protection of Blood and Honor), November 14, 1935 , Deutsches Reichsgesetzblatt, year 1935, Part I, pp. 1334–1336. Austrian National Library

- ↑ Saul Friedländer : The Third Reich and the Jews. The years of persecution 1933–1939 . Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-43506-8 , p. 170 .

- ↑ Peter Longerich : “We didn't know anything about that.” Munich 2006, ISBN 3-88680-843-2 , p. 76.

- ^ Hans Robinsohn: Justice as political persecution. The jurisprudence in "racial disgrace" at the Hamburg Regional Court 1936–43 . Stuttgart 1977, ISBN 3-7610-7223-6 , p. 10.

- ↑ Harumi Shidehara Furuya: Nazi Racism Toward the Japanese: Ideology vs. Realpolitik , NOAG, 157-158, 1995, 17-75, ( PDF ).

- ↑ Harumi Shidehara Furuya: Nazi Racism Toward the Japanese: Ideology vs. Realpolitik , NOAG, 157-158, 1995, p. 65.

- ↑ Harumi Shidehara Furuya: Nazi Racism Toward the Japanese: Ideology vs. Realpolitik , NOAG, 157-158, 1995, p. 64, fn 190.

- ↑ Harumi Shidehara Furuya: Nazi Racism Toward the Japanese: Ideology vs. Realpolitik , NOAG, 157-158, 1995, p. 61, fn 174.

- ↑ Harumi Shidehara Furuya: Nazi Racism Toward the Japanese: Ideology vs. Realpolitik , NOAG, 157-158, 1995, p. 59, fn 166.

- ^ First regulation to the Reich Citizenship Law (1935) .

- ↑ See also "Law for the Unification of the Law of Marriage and Divorce in Austria and the Rest of the Reich Territory of July 6, 1938 (Reichsgesetzblatt I 809)", source: Otto Palandt (editor): " Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch ", 2nd edition, CH Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung , Munich and Berlin 1939, pages 1186 to 1341. Here: "Concept of the Jews and Jewish mongrels" in "Appendix II to § 4 Marriage Act", pages 1200 ff.

- ↑ This provision was already fixed in writing in a discussion about the special Jewish legislation on December 20, 1934: Wolf Gruner (edit.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 , vol. 1. Deutsches Reich 1933– 1937. Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58480-6 , Doc. 146, p. 392.

- ↑ 1933 regarding Martin Wronsky from Lufthansa , see Gerd R. Ueberschär (Hrsg.): National Socialism in front of court . Frankfurt a. M. 1999, ISBN 3-596-13589-3 , p. 89 . “Who is a Jew, determine i!” Is also attributed to Karl Lueger ; see Brigitte Hamann: Hitler's Vienna. Munich 1996, p. 417.

- ↑ John M. Steiner / Jobst F. v. Cornberg: “Arbitrariness within arbitrariness. Liberation from the anti-Semitic Nuremberg laws ”, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 46 (1998), p. 149 or 151 speaks of 6% success. Beate Meyer: "Jewish mixed race". Racial policy and experience of persecution 1933–1945 , Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-933374-22-7 , pp. 105, 108 and 157; thinks higher numbers are likely.

- ↑ Beate Meyer: "Jüdische Mischlinge" , ISBN 3-933374-22-7 , p. 231.

- ↑ Bryan Mark Rigg : Hitler's Jewish soldiers , Paderborn 2003, ISBN 3-506-70115-0 , forms a list on p. 1 as a document of “active officers who themselves or their wives are Jewish mixed race and from the Führer for German-blooded were declared “from where appointments were made in 1943.

- ↑ Uwe Dietrich Adam: Jewish policy in the Third Reich . Unchangeable Reprint from 1972, Düsseldorf 2003, ISBN 3-7700-4063-5 , p. 233.

- ↑ Beate Meyer: "Jüdische Mischlinge" , ISBN 3-933374-22-7 , p. 232 f .; according to a non-representative survey: 4 out of 43.

- ↑ Uwe Dietrich Adam: Jewish policy in the Third Reich , unchangeable. Reprint from 1972, Düsseldorf 2003, ISBN 3-7700-4063-5 , pp. 228-233; Bryan Mark Rigg: Hitler's Jewish soldiers , Paderborn 2003, ISBN 3-506-70115-0 , p. 290.

- ↑ For example, Captain z. S. Georg Langheld, see Georg F. Langheld, Georg Langheld. A Jewish naval officer in the German Wehrmacht, Berlin 2017.

- ↑ In the shadow of the Nuremberg Laws. In: Volkmar Weiss: Prehistory and consequences of the Aryan ancestral pass: On the history of genealogy in the 20th century. Arnshaugk, Neustadt an der Orla 2013, ISBN 978-3-944064-11-6 , pp. 151-178.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz et al. (Ed.): Encyclopedia of National Socialism. 5th edition, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-423-34408-1 , p. 483.

- ↑ Beate Meyer: "Jewish mixed race". Racial policy and experience of persecution 1933–1945. 2nd edition, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933374-22-7 , p. 152.

- ↑ John M. Steiner / Jobst F. v. Cornberg: “Arbitrariness within arbitrariness. Liberation from the anti-Semitic Nuremberg Laws ”. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 46 (1998), p. 162 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Otto Dov Kulka, "The Nuremberg race laws and the German public secret in the light of Nazi attitude and mood reports", in: Quarterly Journal of Contemporary History 32 (1984) 602 f Differentiated Peter Longerich. "Of this we have known nothing . “ Munich 2006, ISBN 3-88680-843-2 , pp. 85-92.

- ^ Declaration by the Reich Representation of Jews in Germany of September 24, 1935 (VEJ 1/201) = The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 . Volume 1: German Empire 1933–1937 , ed. by Wolf Gruner, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58480-6 , p. 499 .

- ↑ Alexandra Przyrembel : "Rassenschande". Purity myth and legitimation for extermination under National Socialism. Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-525-35188-7 , p. 147 .

- ^ Francis R. Nicosia: A Useful Enemy - Zionism in National Socialist Germany 1933-1939. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 37 (1989) issue 3 (PDF) , p. 380.

- ↑ Willy Cohn: No right, nowhere - diary of the fall of Breslau Jewry 1933-1941 , vol. 1. Böhlau 2006, ISBN 978-3-412-32905-1 , pp. 276-277.

- ↑ Jeremy Noakes: Where do the "mixed Jews" belong? … , ISBN 3-7672-0963-2 , pp. 72/73.

- ↑ Arnd Krüger : The Olympic Games 1936 and the world opinion: their foreign policy significance with special consideration of the USA. Bartels & Wernitz, Berlin 1972 (= Sports Science Works , Vol. 7), ISBN 3-87039-925-2 .

- ↑ Germany reports by Sopade. (Edition two thousand and one) Salzhausen and Frankfurt am Main 1980, 2nd year 1935, p. 996.

- ↑ a b Example from Uwe Dietrich Adam: Policy on Jews in the Third Reich . Düsseldorf 2003; first time 1972.

- ↑ Reinhard Rürup: The end of emancipation. Anti-Jewish politics in Germany ... , in: Arnold Paucker et al. (Ed.): The Jews in National Socialist Germany . Tübingen 1986, ISBN 3-16-745103-3 , p. 111 f.

- ^ Saul Friedländer: Das Third Reich ... , Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-43506-8 , pp. 163 , 171.

- ↑ Wolf Gruner (edit.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 , vol. 1. German Reich 1933–1937. Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58480-6 , Doc. 27, pp. 123-129.

- ↑ Alexandra Przyrembel, "Rassenschande": Reinheitsmythos und Vernichtunglegitimation im Nationalozialismus , Göttingen, 2005, p. 138 , see also Wolf Gruner, Deutsches Reich 1933-1937 , Munich 2008, p. 346 with note 4 , draft of the protocol of the Session (BArch R22 / 852, page 75).

- ↑ Alexandra Przyrembel: "Rassenschande". Purity myth and legitimation for extermination under National Socialism. Göttingen, 2005, p. 142 ; Kaveh Nassirin: Martin Heidegger and the legal philosophy of the Nazi era. Detailed analysis of an unknown document (BArch R 61/30, sheet 171). Complete version of the FAZ article Worked against the genocides? of July 11, 2018 ( https://philarchive.org/archive/NASMHU ).

- ↑ Michael Wildt : Politics of Violence. Volksgemeinschaft and the persecution of Jews in the German provinces , in: Werkstatt Geschichte 12 (2003) H. 35, p. 36 f.

- ^ Saul Friedländer: Das Third Reich ... , Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-43506-8 , p. 164 .

- ↑ Peter Longerich: Politics of Destruction , Munich 1998, ISBN 3-492-03755-0 , p. 104, as well as Günter Neliba: Wilhelm Frick: Der Legalist des Unrechtsstaates . Schöningh, Paderborn [a. a.] 1992, ISBN 3-506-77486-7 .

- ↑ Jeremy Noakes: "Where are the 'Jews mongrels?" The emergence of the first regulation implementing the Nuremberg Laws , in: Ursula Büttner et al.. (Ed.): The Unlawful Regime ..., Volume 2: Persecution, Exile, A New Beginning With A Load. Hamburg 1986, ISBN 3-7672-0963-2 , p. 73.

- ↑ see Emmanuel Faye: The National Socialism in Philosophy. Being, historicity, technology and destruction in Heidegger's work. In: Hans Jörg Sandkühler (Ed.): Philosophy in National Socialism Meiner, Hamburg, 2009; another., Heidegger. Introducing National Socialism into Philosophy. In the context of the unpublished seminars between 1933 and 1935 , Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2009 [fr. Original: Heidegger, l'introduction du nazisme dans la philosophie: autour des séminaires inédits de 1933-1935 , Paris, 2005], p. 135 f .: Victor Farías has "shown that Heidegger (...) is committed again (...) ) for example through his active participation (...) in a committee for legal philosophy, which (...) was charged with legitimizing the future Nuremberg Laws "; Farías does not refer to the Nuremberg Laws in the context, pp. 277–279; ders., The coronation of the complete edition , a conversation with Iris Radisch , Zeit Online from December 27, 2013, edited on January 2, 2014: “Heidegger accepted, however, with Alfred Rosenberg and Julius Streicher to the committee for legal philosophy of the academy for German law who had worked to legitimize the Nuremberg race legislation ”; S. Kellerer / F. Rastier: Reply to Hermann Heidegger's letter to the editor in Die Zeit : "The committee played a key role in the preparation of the Nuremberg Laws"; François Rastier, The Conversation , November 1, 2017, Heidegger, théoricien et acteur de l'extermination des juifs? : "Une telle commission, dont tous les membres sont partisans d'une extermination totale de juifs et dont la première tâche concrète est de contribuere à l'élaboration des lois de Nuremberg promulguées dès l'années suivante"; F. Rastier, Liberation v. November 5, 2017, Un antisemitisme exterminateur

- ↑ Norbert Frei: The Führer State. National Socialist rule 1933 to 1945 , Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-64449-8 , p. 148.

- ↑ Quoted from Andreas Brämer; Miriam Rürup (eds.), Ina Lorenz, Jörg Berkemann, The Hamburg Jews in the Nazi State 1933 to 1938/39: Hamburg Contributions to the History of German Jews , Göttingen, 2016, p. 114 fm note 84 .

- ↑ here sums in the territorial status of May 17, 1939 (Germany, Austria, Sudeten German areas, but without Memelland) according to Die Juden und Jewish Mischlinge in the German Reich , in: Volkszählung. The population of the German Reich according to the results of the 1939 census. Statistics of the German Reich, Bd. 552, H. 4, Berlin 1944.

- ↑ Alexandra Przyrembel names in her book "Rassenschande" - Purity Myth and Extermination Legitimation in National Socialism (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2003, p. 414 ff. ) Four death sentences for Berlin in 1943 as well as another one based on the fact that a man with a criminal record was convicted as a moral criminal sold out on a 13-year-old boy, one for Leipzig on June 6, 1942 and one on August 25, 1942, another each in Hamburg on April 24, 1941 and September 12, 1942 as well as in Kassel, Nuremberg, Cologne and Stettin , also in Hamburg on August 2, 1940, which also involved forging food cards , in Leipzig in March 1942 for racial disgrace and bicycle theft, and in Gdansk in January 1940, where the death penalty was justified by the accused hiding his Jewish identity and committed forgery and fraud.

- ↑ Cornelia Essner / Edouard Conte: "Fernehe", "Leichentrauung" and "Totenschescheid". Metamorphoses of marriage law in the Third Reich , in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte . Volume 44 (1996), issue 2, p. 227 ( PDF ; 7 MB) / numbers see Beate Meyer: “Jüdische Mischlinge” , Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933374-22-7 , p. 469.