lithography

The lithography or lithography (from the Greek. Λίθος lithos "stone" and γράφειν graphein "write") is the oldest method of lithographic printing and belonged in the 19th century to the most widely used printing techniques for color prints, it is also referred to as a reaction printing process. Lithography is used to describe:

- the stone drawing as a printing template and printing form for reproduction using the stone printing process,

- the print (color transfer) from the stone onto suitable paper in the lithographic press as the result of this reproduction,

- the artisanal or machine lithography process itself.

A lithographer is someone who makes the stone drawing - i.e. the texts and images to be printed - on a lithographic stone manually and in reverse.

The lithographic printing is based on an invention by Alois Senefelder from 1798. In the 19th century, it was the only printing process that allowed larger editions of colored printed matter. In Germany, a limestone slate that was quarried in Solnhofen in Bavaria was used as the printing form . Up to 1930, lithographic printing was a very common printing technique for various types of printed matter, but was then gradually replaced by offset printing and is now only used in the artistic field. For today's mass production of printed matter, lithography is unsuitable because it is uneconomical compared to other modern printing techniques.

Printing process

Today, according to DIN 16500, a distinction is made between four main printing processes, namely letterpress, gravure, through and flat printing . In each of these printing processes, the name refers to the relationship between printing and non-printing areas on the printing form . In letterpress printing, the printing parts are raised, while the non-printing parts are recessed. The opposite is true for gravure printing. When printing through, the printing form consists of a screen-like stencil in which the printing areas are color-permeable, while the non-printing areas are impermeable ( screen printing ). Finally, with planographic printing, the printing and non-printing areas lie in one plane. The principle here is based on the chemical contrast between fat and water. While the printing areas are fat-friendly, the non-printing areas are moistened with a film of water and repel the fat-rich printing ink.

Stone printing is one of the flat printing processes and is based on the fact that a damp stone is rolled in with greasy paint, which, however, repels the color, because grease and water do not combine but repel each other. However, the drawing previously applied to the stone takes on the printing ink. If the stone is now covered with a specially coated paper or cardboard, the drawing is transferred from the stone to the paper using high pressure. A lithographic press is required for this printing process.

Materials, tools and techniques

Lithography stone

Every printing process requires a print template , i.e. a medium that contains the texts, drawings and images to be printed. The lithographic stone is used for this in stone printing. In the trade, lithography stones are offered in different thicknesses between 5 and 10 cm. The most abundant deposits are mined in France near Dijon , in Switzerland in Solothurn and in Germany in Solnhofen . Solnhofen limestone is considered to be the world's best material for lithographic printing plates.

The quality of a lithographic stone correlates with its color. A yellow stone is of inferior quality, as it can absorb a lot of water due to its molecularly open structure and therefore does not allow clean printing. A gray stone is molecularly denser and therefore gives better printing results. Solnhofen limestone is gray-blue in color. Its consistency is even denser, which means that it has even better printing properties.

Lithography stones are ground before use. This process can be done manually or in a grinding machine. New stones must be ground flat; stones that have already been used must be freed from the previous print image. Depending on the intended drawing technique, the stone is ground smooth, grained or polished.

In order to be used in lithography, the stones must have a predetermined thickness so that they do not break under the pressure of the lithographic press. The required thickness is around 8-10 cm; In order to achieve this, the stone on which the printing surface is located is glued or plastered onto a second of inferior quality. It is crucial that the stone is absolutely plane-parallel and has the same thickness everywhere. However, it does happen that the stone breaks during printing.

Lithographic ink and chalk

To manually transfer a drawing to the stone, the lithographer needs a pen and lithographic ink . This ink consists of the basic substances wax, fat, soap and soot . A distinction is made between industrially produced liquid ink and so-called stick ink. The rod ink must be rubbed with distilled water for use.

Lithographic chalk is available in the form of pens and square sticks that are clamped in a holder. There are six degrees of hardness, with 0 being the softest and 5 being the hardest. Chalk is made up of the same substances as lithographic ink. The soft chalk is suitable for dark areas and shadows, while the harder grades are used for fine gradations.

Drawing devices

Lithographic ink is transferred to the stone with a steel drawing pen. These are special feathers that are softer than common drawing pens. If a nib becomes dull from use, it can be sharpened on an Arkansas oil stone if necessary to create fine lines or dots. Another important tool is the scraper to make corrections to the drawing like with an eraser. The lithographer has a whole range of narrow and wider scrapers, which often have to be sharpened with the help of the oil stone.

Drawing table

If possible, the stone should not be touched with the hand, as every fingerprint leaves greasy traces. That is why the lithographer works on a specially constructed lithography desk or table. The commercial chromolithographer worked standing or sitting at a wooden desk. He had a height-adjustable wooden swivel chair without a back to sit on. The desk was inclined slightly from the back to the front and the two side walls protruded about 10–12 cm above the table top. A so-called wooden bracer was placed over the table top. Below was the lithographic stone, which could now be worked on with a pen or a scraper without touching it with the hand. Today artists use similarly designed tables for their lithographic work.

Creation of the print image

There are various techniques available to the lithographer to transfer the print image onto the stone.

Lithographic Techniques

In spring technology , a pen drawing is applied directly to a smooth stone. As a rule, the lithographer needs a preliminary drawing as a guide. He uses tracing paper onto which the contours of the original drawing are transferred. Then the reverse side of the transparent paper is rubbed with graphite or red chalk, and the paper is positioned and attached the wrong way round on the stone. The lithographer traces the contours with a steel needle and transfers them onto the stone in a clearly visible manner. Today , artists use an episcope to project a photo of the subject onto the stone and trace the contours.

Spring technology is one of the oldest processes in lithography. The drawing is reversed with the steel pen or the Bourdon tube and lithographic ink onto the surface of the stone, which has previously been sanded smooth. The lithographer makes minor corrections with a scraper. When the picture is ready and the ink is dry, the stone is rubbed with talc and then gummed with gum arabic as protection.

In preparation for a chalk lithograph , the stone is granulated with sand, giving it a rough surface. Quartz sand was previously used for graining . Today silicon carbide is used , which is commercially available in various grain sizes, from coarse, medium and fine. As with spring technology, the printed image is reversed onto the stone. The chalk is sharpened from the tip with a sharp knife. Depending on the tonal value of the drawing, the lithographer chooses hard chalk for light areas and softer chalk for darker areas of the image. Here, too, minor corrections can be made with the scraper. Chalk lithography is one of the most expressive techniques in graphics. By wiping with a special wiper, the Estompe , and rubbing in the chalk, you can achieve a dim effect with soft transitions, for example. The finished drawing is then treated again with talc and gum arabic.

The carving was used especially for business cards, letterheads and securities due to their fine line drawing. The lithographer uses a gray-blue stone of the highest quality, which is first ground and then polished with clover salt . The poisonous clover salt is a potassium oxalate and forms a compound with the limestone, in which the pores are closed and the user creates a mirror-smooth surface by polishing with a tampon. Then the stone is covered with a dark colored layer of gum arabic. Here, too, a preliminary drawing is first made as a guide before the lithographer scratches the drawing with an engraving needle or an engraving diamond. The needle pierces the rubber layer and the lines in the stone surface may not be more than 0.2 mm deep. The stone is then soaked in olive oil before the lithographer removes the rubber layer with water. Although the engraved lines are deeper in the stone, they can be colored with a rough leather roller or with a tampon. The absorbent paper has to be moistened slightly so that it clings better to the stone and takes on the color.

Create halftones

Before the invention of the screen , so-called halftones could only be created using manual techniques. There are the following options in lithography:

In the pen dotting manner, pen and ink are used to manually place point by point on the stone. The point density and size depends on the respective tonal value of the original. The best known technique in chromolithography is called Berliner Manner , in which the lithographer places the dots together in a semicircle. The colored lithographs often consisted of twelve or more colors printed one on top of the other, which differed greatly in brightness. The lighter colors were roughly dotted and the tones were even underlaid over the entire surface. The darker, drawing colors were done by the best lithographers who could set particularly fine points.

The Tangier manner eventually supplanted the pen-dotting manner partly because it was significantly simpler. Here a hardened gelatine film already bears the desired pattern of dots, lines or other shapes, which is transferred directly to the stone by pressing it after it has been colored. Areas that should remain free are covered with a repellent layer of gum arabic. However, this technique is only suitable for smooth semitones. Gradients and shading cannot be created with it.

In the spraying manner , which was already known to Senefelder, an ink-soaked brush is passed over a sieve, which is held at a certain distance over the stone. Here, too, the areas where no paint should later adhere are covered with gum arabic. A gradation of the tone values is generated by the frequency of the spraying process.

In the scraping manner , also called asphalt or ink manier, an asphalt layer is applied over the entire surface of a grained stone . After drying, the light areas of the image are lightened according to the original using a scraper, sandpaper and lithographic needles. The process is particularly suitable for fine tonal gradations. When the drawing is done, the stone is treated with a strong caustic solution of gum arabic and seven percent nitric acid.

Preparing the stone for printing

The drawing on the stone cannot be printed without preparation. The lithographer and the lithographer call this chemical process etching . The fat-friendly printing parts, i.e. the drawing, should be reinforced in their properties and the non-printing parts of the stone should remain fat-repellent and water-absorbent. The etch consists of a mixture of nitric acid , gum arabic and water, which is applied to the stone surface with a sponge and takes effect. Nothing is removed or etched away by the etching, but only optimizes the printing properties of the stone. The process can be repeated several times and is considered complete when the first test prints have been made without any changes.

In addition to specialist knowledge, a lot of experience is required for this activity. This is why artists today have their lithographs treated by an experienced lithographer on a commission basis in order not to endanger the result of their work.

Lithograph

In lithographic printing, a distinction is made between the hand press and the high-speed press . Today, in addition to a few high-speed presses, there are still a few hand presses in operation in Germany that produce prints for artists. The most famous hand press or toggle press was built in 1839 in the workshop of the locksmith Erasmus Sutter in Berlin and is more of a tool than a machine. The frame of the hand press is made of heavy cast iron, in which there is a cart or wagon and a roller with which the stone can be moved back and forth manually. The pressing pressure is done by pressing down a friction, under which the carriage with the stone is pulled through. The paper to be printed lies between the stone, which was previously rolled in with printing ink, and the grinder, and above it is a firm, smooth cardboard called a press cover or pressboard . After removing the press cover, the printed sheet is carefully lifted off and examined. In order to set the correct pressure, the lithographer needs experience and instinct. For each hand press there are graters of different widths, which are adapted to the respective stone size.

With the further development of lithography in the 19th century and the growing need for printed matter, the hand press could no longer meet the requirements. This requirement was met by the high-speed lithographic press, with an hourly printing capacity of around 800 sheets. The considerably larger stone was not printed by means of a grater, but by means of a roller. The inking unit ensured that the paint was evenly distributed on the paint table, which was picked up by further paint rollers and transferred to the stone. Dampening rollers took over the necessary moistening of the stone. The carriage with the stone first ran under the dampening rollers, further under the inking rollers and finally under the impression cylinder. The paper was on the cylinder, which was covered with a rubber blanket, was then printed on and placed again on the delivery table. The sheet to be printed was created manually, mostly by women. The high-speed press was initially driven manually, but later by steam engines via drive belts .

In contrast to modern four or six-color machines, this high-speed lithographic press could only print one color at a time. This meant that with a twelve-color lithograph, the printing process had to be repeated twelve times. It is easy to imagine how elaborately colored pictures were produced back then.

Transfer printing

The term transfer printing or autography summarizes methods with the help of which drawings or prints are transferred from the paper to the lithographic stone. Transfer printing processes include overprinting , in which a drawing is printed from one stone onto special transfer paper and then transferred to a second stone, for example a machine stone. This process is repeated until the significantly larger machine stone contains many drawings corresponding to its size. The transfer paper is provided with a water-soluble line that forms a separating layer between drawing or print and paper. It is moistened, placed on a second stone and transferred under pressure. The paper is now moistened again until it can be peeled off easily. The drawing is now visible in all details on the second stone and can be treated like a normal lithograph.

The machine stone used in the high-speed stone printing press usually contained lithographs that were produced using the transfer printing process. Depending on the number of copies, a certain number Umdrucke or benefits , so copies of the original lithograph made.

The clap or gossip was used in chromolithography to provide the number of stones with the contours of the printed image according to the number of colors. The lithographer made a drawing of the original picture from fine lines, which contained outlines and color differences and served as a preliminary drawing for the later chromolithography. Transfer paper was also used for this purpose, but with so little color that the outlines of the preliminary drawing did not later take on any printing ink.

Many artists have made use of transfer paper, in addition to Honoré Daumier and Toulouse-Lautrec , Emil Nolde , Ernst Barlach , Henri Matisse and Oskar Kokoschka . However, this technique results in a slight loss of quality in the print image.

Chromolithography

Senefelder already dealt with the color reproduction of writings, maps and pictures. He underlaid a chalk lithograph with a clay plate, a chamoiston, from which the lights were removed using a scraping technique. The viewer gave the impression of a multicolored lithograph.

In 1837, the Franco-German lithographer Godefroy Engelmann (1788–1839) from Mulhouse patented a color variant of lithography under the name Chromolithography (color stone printing , color lithography), which was to remain the most popular method for high-quality color illustrations until the 1930s . Chromolithographs consisting of up to 16, 21 and even 25 colors were not uncommon. However, it was evident that this was a very time-consuming and costly process. After the introduction of the lithographic high-speed press around 1871, large quantities of color lithographic printed matter were produced, as larger print runs were now possible.

The chromolithographer used a painted picture as a template or original. In the first step, a contour drawing was made on stone. It was a drawing made of fine lines, which marked the outlines and color differences of the original. This contour plate served the lithographer as a guide for the precise elaboration of the intended individual colors. Using the transfer printing process, copies of the contour plate called gossip were then made on a number of stones that corresponded to the number of colors provided. The swatter only hinted at the contours in a light shade and later disappeared during the print preparation of the finished chromolithography.

After the lighter colors had been worked out, printing was started. With the help of thin crosses, which were called pass marks or pass marks , the motif to be printed could be printed over each other precisely and accurately across all colors. This process was called needling the proofs. Before that, the lithographer had drilled a tiny hole in the middle of the registration marks on the right and left of the stone. These holes were repeated on the paper to be printed, which could now be precisely positioned on the stone with the help of two needles. After printing each color, the chromolithographer checked the progress of his work and then processed the next darker color. Finally the finished proof was presented to the customer, who could now express his change requests. After the appropriate correction, the order was ready for printing and the edition could be printed in the lithographic high-speed press.

Since the machine block was considerably larger than the pressure block, several transfers were made from the original lithograph depending on the number of copies. If the machine stone was not yet filled out, there was space for additional orders on the stone. The edition print from the machine stone should come as close as possible to the result of the proof, despite a slight loss of quality.

Photolithography

→ Main article: Photolithography (printing technology) → Main article: Photolithography (historical printing technology)

The French Niépce copied photographic negatives onto the litho stone in 1822. However, there was still no way to resolve the photographic image into printable halftones. Georg Meisenbach is considered to be the inventor of the glass engraving grid, who developed the high-precision glass engraving grid in 1881 and was therefore able to break down halftones into printable halftone dots for the first time by photographic means. This rasterization took place in a reproduction camera in which a raster disk was placed in front of the photographic plate to be exposed. Due to the differentiated tonal value reproduction, this technology enabled printed reproduction in six or four colors instead of twelve or more and was thus far more economical than conventional chromolithography.

The repro photographer used color filters to create the required color separations . The photolithographer processed the negatives on glass produced in this way with Farmer's attenuator to lighten them and with blue Keilitz paint to darken them. Non-printing areas were made opaque with red chalk or masking red . The finished retouched negatives served as templates for the stone copy . A prepared stone was made photosensitive with an egg white chromate solution. This consists of a solution of distilled water , dry protein, ammonia and ammonium dichromate , with which the stone was poured and evenly distributed in a centrifuge and dried. The photolithographer then placed the retouched negative layer upon layer on the stone and weighed it down with a glass plate. The areas outside the negative were given a cover made of black paper. The exposure to carbon arc light was carried out in a stone copier , as a result of which the exposed areas were hardened. The stone was then rolled in with black printing ink and the copy was developed with a cotton ball in a shallow basin filled with water. The unexposed areas came loose and a positive reversed color separation appeared on the stone. This could now be edited manually again before the stone was prepared for printing.

A similar process was asphalt copying, in which the stone was made photosensitive with a solution of asphalt , turpentine , benzene and chloroform . However, this method was extremely dangerous to health.

After lithography had been superseded by offset printing , only the misleading job title " photolithographer" remained , although this job no longer had anything to do with a lithographic stone . The later correct job title was artwork preparer - specializing in offset printing .

History of lithography

Alois Senefelder

Alois Senefelder is considered to be the inventor of stone printing, which he developed between 1796 and 1798. The theater writer could not find a publisher to print his manuscript for a play he had written himself. Senefelder then wanted to publish it himself and, due to lack of money, tried to find an inexpensive and simple method of reproduction. Since all the substances needed for lithography were available to him from the theater, he first tried to use the etching technique to etch the background of the printing template for letterpress printing, which proved to be impractical due to the immense etching effort. Finally he discovered the repulsion reaction of fat and water only on Kelheimer plates later on Solnhofen plate limestone and developed flat printing from it.

Hardly any technical invention has been described as meticulously as it is the case in Senefelder's textbook on stone printing . There he describes the laborious, often unsuccessful attempts that finally led to his invention. In 1796 he succeeded for the first time in the mechanical printing of a stone and two years later in the first chemical printing . After a total of seven years of experiments and unsuccessful attempts, Senefelder achieved the breakthrough and since then he has been considered the inventor of the chemical printing plant , as he called the new process. Senefelder worked on the further development of his technology until his death in 1834. He tried printing with metal plates, constructed a portable suitcase press and improved the chemical composition of lithographic ink and chalk.

A new business emerges

Since 1803 the new technique was called lithography in France . Initially, stone printing was only used for non-artistic purposes such as printing text and music . The music publisher Johann Anton André from Offenbach am Main initiated the use of lithography for the reproduction of visual representations. In addition, lithography in conjunction with lithographic presses was an economical mass printing process that allowed reproductions in large editions for the time.

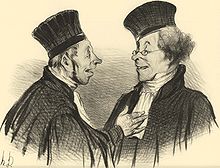

Lithography therefore not only quickly became an autonomous art form that allowed the painter and draftsman to preserve the original character of the drawing. In the days before photography, it was also a fast medium for the press to depict current events. One of the first to take up this medium was Honoré Daumier , who attacked the political situation from around 1830 to 1872 through his caricatures published in critical magazines. His approximately 4,000 lithographs appeared mainly in the magazine “ Le Charivari ” and are now accessible digitally with interactive search functions in the Daumier register.

The picture sheets from Neuruppin , which reported on important political events and terrible catastrophes or taught about virtues or warned of the effects of vices , were a special way of preparing daily news from that time . The last picture sheet was not printed until the 1930s.

The increasing demand for colored pictures was initially satisfied with the subsequent coloring of originally monochrome lithographs. This manual process required artistic skill and was at the same time time consuming.

The multi-colored stone printing

In 1837, the Franco-German lithographer Godefroy Engelmann developed a colored variant of lithography and called it chromolithography . As high-quality as the chromolithographs were - the highest quality printing process ever after collotype printing - their execution was just as complex. The picture to be printed in color was broken down into up to 25 colors and then printed on top of each other in as many print runs. The printing was done from light to dark - first the lightest color was printed, then the darker one. The finished picture achieved a color quality that was almost comparable to that of an oil painting. The newly created businesses were called Lithographic Art Institutes .

Well-known publishing houses such as the Bibliographisches Institut Leipzig and Vienna employed large departments towards the end of the 19th century that were only concerned with this high art form of lithography technology. In Austria, Karl Antal Mühlberger further developed lithography so that it could also be used in large format and, above all, inexpensively in advertising. Between 1855 and 1880, the number of lithographic products increased twenty-fold. Aschaffenburg, Berlin, Barmen, Hamburg and Nuremberg developed into centers of the lithographic trade. In 1898, there were almost 180 businesses in Berlin alone, including almost 25 lithographic art institutions with 100 to 500 employees. The Hagelbeck company in Berlin employed 750 people and the machine park consisted of 42 high-speed lithographic presses.

Lithography quickly became the leading reproduction technique for advertising and advertising. As a result of this new, inexpensive technology, advertising posters and advertising pillars began to change the cityscape. French artists such as Jules Chéret and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec played a leading role in the development of the early posters . Toulouse-Lautrec preferred large-format sheets, combined with an easy-to-use coloration of a few colored stones in yellow, red and blue, which also radiated an effect from a distance.

The triumphant advance of the poster around 1900 quickly created a need for commercial graphic artists who initially came from other branches with a focus on representation, as well as architects and painters. From this the profession of poster painter or commercial graphic designer and later graphic designer developed around the turn of the century . Until the 1950s, drawn film posters were produced using stone printing.

Lithography was also used as a printing technique for postcards , advertising closure stamps , labels or the so-called Liebig pictures and postage stamps . In addition, lithography was used for packaging in the food and luxury food industry, equipment for the cigar and cigarette industry, securities, check forms, collector's pictures, industrial pictures and decals and much more.

A good 150 years passed between the invention of lithographic printing in 1798 and its replacement in the 1950s. After 1920, other techniques pushed stone printing back down to a few areas, such as tin printing, printing of decals, cartographic maps and artistic graphics. Chromolithographs in particular are coveted collector's items today, which fetch high prices in the specialist market in the form of whole books or in single sheets.

The apprenticeships lithographer and lithographer were deleted from the apprenticeship roles of the chambers of industry and commerce in 1956. Since then there has been no commercial training in these professions. Interested parties can acquire basic knowledge by studying at technical colleges or art colleges.

19th and 20th century artists

From Munich, the new technology quickly spread throughout Germany. Lithography was quickly adopted by artists in the early 19th century because it offered them a wide variety of new design possibilities. The artist did not need special chemical knowledge, as with etching or aquatint , nor did he have to overcome the resistance of the material with tools, as with copper engraving . The first lithographed landscapes appeared as early as 1800. One of the first artists was Matthias Koch at the beginning of the 19th century, who drew the romantic landscapes popular at the time with fine pen and chalk lines on the stone. Johann Nepomuk Strixner lithographed and printed Albrecht Dürer's marginal drawings for Maximilian I's prayer book in 1809 .

Francisco de Goya , over 70 years old , was the first artist to use the chalk technique to lithograph in his bullfight cycle Los Toros de Burdeos . In France, a new art form in chalk lithography developed within a short time by Ingres , Géricault , Delacroix , Daumier , Steinlen and other artists. Theodore Géricault had been interested in stone printing since 1817 and shaped a personal style through his chalk lithographs showing pictures of horses and streets. Eugène Delacroix dealt with illustrations for Goethe's Faust and Shakespeare's Hamlet. He also preferred chalk lithographs, which he then worked on with a scraper and steel brush.

Honoré Daumier used chalk lithograph as an artistic medium in the 1830s to critically examine politics and the everyday worries of his fellow human beings. In the course of his life he created around 4,000 drawings, making him the most productive artist of his time. Daumier's works were seen as passionate accusations against political and social ills in French society and often sparked press censorship.

In the illustration, botanical garden magazines took over in 1834, Walter Hood Fitch by William Jackson Hooker used as his successor, the post of chief illustrator of Curtis's Botanical Magazine and all publications of the Royal Botanic Gardens (Kew) . Fitch remained chief lithographer for 43 years until 1877, during which time he produced several thousand illustrations that made him the most important and by far the most productive plant illustrator not only of the Victorian era, but also in general. Fitch was not only employed for the illustrations by the later director of the Royal Botanic Garden, Kew, Joseph Hooker over the long period , he was almost exploited in it, as he made over 9,900 illustrations, but received little money for it, which led to the break in 1877 . Fitch also furnished the lavish lily monograph by Henry John Elwes with illustrations, including the panel with Lilium dalmaticum .

After 1841, Fitch became the sole artist for Kew's official and unofficial publications. Hooker paid Fitch personally for this. He was able to draw for different publications simultaneously and often produced his illustration directly on the lithographic limestone slabs to save time.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec's work appeared around 1880 at a time when chromolithography had conquered the market. He worked with the same obsession as Daumier, but color became an important means of expression for him. Adolph von Menzel from Germany should be mentioned. His works from the 1880s are among the masterpieces of lithography.

Other well-known Impressionist artists who also contributed to the development of color lithography were Camille Pissarro , Paul Cézanne , Alfred Sisley and Edgar Degas at the end of the 19th century . Edvard Munch , who visited Paris several times around 1890, was inspired by lithography. In England Richard Bonington , Charles Shannon and James Whistler worked with lithography.

In Germany Emil Nolde especially valued the possibilities of lithography and created many technically interesting lithographic works. Käthe Kollwitz was one of the few women who used lithography as a pictorial means of expression around 1890. Its very dark leaves provide an insight into the life of German working-class families. The members of the artist community Die Brücke at the beginning of the 20th century and German Expressionists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner , Oskar Kokoschka and Lovis Corinth created lithographic works that impressed with their spontaneity.

Pablo Picasso's lithographic repertoire ranged from chalk drawings to ink and pen drawings to brush wash in various shades of gray. He was fascinated by the technical possibility of printing and varying what was drawn. Also, Joan Miró turned out to be sovereign masters in the lithographic techniques.

Well-known lithographers

See also

- Autography , autotype , graphics , printing technology

- Photolithography (microlithography) for modern lithography processes in the semiconductor and electrical industries

- Nanolithography

- Granolithography

- Offset lithography

- Stone abrasion

literature

A comprehensive compilation of historical handbooks on lithography with links to digital copies can be found at Wikisource .

- Michael Twyman: History of chromolithography: printed color for all . British Library et al. a. London et al., 2013, ISBN 978-1-58456-320-4 .

- Helmut Hiller, Stephan Füssel: Dictionary of the book. Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-465-03220-9 .

- Mario Derra: The Solnhofen natural stone and the invention of flat printing by Alois Senefelder. A lithography guide. Bürgermeister-Müller-Museum, Solnhofen 2002, ISBN 3-00-009414-8 .

- Michael Twyman: Early lithographed music: a study based on the H. Baron Collection. Farrand Press, London 1996, ISBN 1-85083-039-8 .

- Jürgen Zeidler: Lithography and stone printing in trade and art, technology and history. Ravensburger Buchverlag, Ravensburg 1994, ISBN 3-473-48381-8 .

- Hans-Jürgen Imiela , Claus W. Gerhardt : History of the printing process. Part 4: Stone and offset printing, additions and general register. Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-7772-9309-1 .

- Michael Twyman: Early lithographed books: a study of the design and production of improper books in the age of the hand press. Farrand et al., London 1990, ISBN 1-85083-017-7 .

- Walter Dohmen : The lithography. History, art, technology (= Dumont pocket books 124). DuMont Verlag, Cologne 1982, ISBN 3-7701-1431-0 .

- Aleš Krejča: The techniques of graphic arts. Manual of Operations and History of the Original Printmaking. Werner Dausien publishing house, Hanau a. M. 1980, ISBN 3-7684-1071-4 .

- R. Armin Winkler: The early days of German lithography. Catalog of the prints from 1796–1821. Prestel, Munich 1975, ISBN 3-7913-0077-6 .

- Michael Twyman: Lithography, 1800-1850 The techniques of drawing on stone in England and France and their application in works of topography. Oxford University Press, London et al. 1970, OCLC 251516647 .

- Wilhelm Weber : Saxa Loquuntur - stones talk - history of lithography. 2 volumes. Impuls Verlag Moos, Heidelberg / Berlin 1961–64, DNB 455397368 .

- Alois Senefelder : Complete textbook of the stone printing company. Fleischmann, Munich 1818; 2nd edition 1821 (digitized) .

- DVD: The lithography. Manual lithography in art. Year of production: 2009/2010, running time: 31 minutes, produced by the Käthe Kollwitz Museum der Kreissparkasse Köln, director: Matthias Keuck.

Web links

- Homepage of the lithographer Theo de Smedt

- Gutenberg Museum Mainz, museum for the history of books, printing and writing

- Internet presence of the Daumier Register

- Nederlands Steendrukmuseum

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jürgen Zeidler: Lithography and stone printing. Ravensburger Buchverlag, 1994, ISBN 3-473-48381-8 , p. 7.

- ↑ Jürgen Zeidler: Lithography and stone printing. 1994, pp. 8-10.

- ^ Walter Dohmen: The lithography. History, art, technology. DuMont paperback books, Cologne 1982, ISBN 3-7701-1431-0 , pp. 47–54.

- ^ A b Walter Dohmen: The lithography. History, art, technology. 1982, pp. 54-55.

- ↑ a b c Jürgen Zeidler: lithography and stone printing. 1994, pp. 28-31.

- ↑ Jürgen Zeidler: Lithography and stone printing. 1994, p. 29f.

- ↑ Jürgen Zeidler: Lithography and stone printing. 1994, p. 31f.

- ↑ Jürgen Zeidler: Lithography and stone printing. 1994, p. 42.

- ↑ Jürgen Zeidler: Lithography and stone printing. 1994, pp. 29-30.

- ↑ Jürgen Zeidler: Lithography and stone printing. 1994, p. 36.

- ↑ Jürgen Zeidler: Lithography and stone printing. 1994, p. 33f.

- ↑ Jürgen Zeidler: Lithography and stone printing. 1994, pp. 39-42.

- ^ Walter Dohmen: The lithography. History, art, technology. 1982, pp. 170-176.

- ↑ a b Jürgen Zeidler: lithography and stone printing. 1994, pp. 66-70.

- ↑ a b c Walter Dohmen: The lithography. History, art, technology. 1982, p. 123 ff.

- ↑ a b c Jürgen Zeidler: lithography and stone printing. 1994, pp. 84-89.

- ↑ Jürgen Zeidler: Lithography and stone printing. 1994, pp. 36-38.

- ↑ a b c Photolithography ( memento of July 3, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on June 29, 2009.

- ↑ Martin Röper, Monika Rothgaenger: Altmühltal In the realm of Archeopteryx. Forays into the history of the earth. Quelle & Meyer Verlag, Wiebelsheim 2013, ISBN 978-3-494-01488-3 .

- ↑ Jürgen Zeidler: Lithography and stone printing. 1994, p. 105.

- ↑ a b Jürgen Zeidler: lithography and stone printing. 1994, p. 110ff.

- ↑ a b c d Jürgen Zeidler: lithography and stone printing. 1994, p. 84ff.

- ↑ a b c d e Walter Dohmen: The lithography. History, art, technology. 1982, p. 23ff.

- ^ Jack Kramer: The Art of Flowers . Watson Guptill Publications, New York 2002, ISBN 0-8230-0311-6 , p. 152.

- ^ William T. Stearn: Flower Artists of Kew . The Herbert Press in association with The royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, London 1990, ISBN 1-871569-16-8 , p. 27.

- ^ William T. Stearn: Flower Artists of Kew. 1990, p. 27.

- ↑ Miguel Orozco: Picasso lithographer and activist . 2018 ( academia.edu ).