denazification

As denazification (contemporary and outdated also Entnazisierung , denazification or Denazifikation ) is converted, from July 1945 policy of the Four Powers referred that was aimed, the German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary and politics from all influence of Nazism to to free.

The basis for denazification were the resolutions passed at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, the JCS 1067 directive issued by the US State Department of April 26, 1945, and the resolutions of the Potsdam Conference of August 1945.

The common goal of denazification was to be achieved through a package of measures that included comprehensive democratization and demilitarization . The most important goal was the dissolution of the NSDAP and its affiliated organizations.

Denazification also included the prosecution of war crimes committed during World War II and the internment of people who appeared to be a security risk for the occupation forces.

Group of people

In January 1946 the Allied Control Council in Berlin passed the Control Council Directive No. 24, which in Art. 10 defined in detail the groups of people who should be forcibly removed from public and semi-public offices and from positions of responsibility in important private companies and replaced by such persons, " who, according to their political and moral attitudes, were deemed capable of promoting the development of true democratic institutions in Germany ”. These included first and foremost those people who were on the war criminals list of the Allied War Crimes Commission , then full-time party members such as the Reich and Gauleiter as well as those who were full-time in the party branches and the affiliated and supervised party associations , as well as civil servants and lawyers.

Persons who, as “staunch supporters of National Socialism, would probably perpetuate undemocratic traditions” such as professional officers of the German Wehrmacht or persons who embodied the Prussian Junker tradition should, according to Art. 11 should be carefully checked and, if necessary, removed at the discretion . Art. 12 contained discretionary criteria that linked to more than just nominal membership in other Nazi organizations such as voluntary membership in the Waffen SS or membership in the Hitler Youth and the Bund Deutscher Mädel with membership before March 25, 1939. In addition, close relatives of prominent National Socialists should not be employed. It is "essential that the leading German officials at the head of provinces, administrative districts and districts are proven opponents of National Socialism, even if this entails the employment of people whose aptitude to fulfill their tasks is less" (Art . 13).

Implementation in occupied Germany

The victorious Allied powers had adopted general principles for political cleansing at the Potsdam Conference, but did not agree on common procedures and targets. Each occupying power proceeded with different degrees of severity and different basic schemes. Mass arrests have not started everywhere. In total, there were around 182,000 internees in the three western occupation zones alone, of whom around 86,000 had been released from the denazification camps by January 1, 1947. Until 1947 the following were imprisoned:

- British Zone 64,500 people (34,000 laid off = 53%)

- American Zone 95,250 (laid off 44,244 = 46%)

- French zone 18,963 (dismissed 8,040 = 42%)

- Soviet zone 67,179 (laid off 8,214 = 12%).

There were 5025 convictions in the western zones. Of these, 806 were death sentences, of which 486 were carried out.

In the three western zones, the 2.5 million Germans whose proceedings had been decided by December 31, 1949 by the ruling chambers , which were mostly made up of lay judges , were judged as follows:

- 54% followers,

- the case was discontinued in 34.6%,

- 0.6% were recognized as Nazi opponents,

- 1.4% mainly guilty and incriminated (guilty).

Many of the followers deeply involved in the Nazi past were able to pursue a career in the Federal Republic of Germany after 1949. They went back to politics, the judiciary, administration, the police and the universities with Persil certificates that were issued to them by (alleged) victims for the judging commissions and ruling chambers ; often under a false name and often with the help of the networks ( rat lines ) of old comrades or of " rope teams ". In the 1950s, for example, more than two thirds of the senior staff at the Federal Criminal Police Office were former members of the SS . This failure to actually come to terms with the past was reinforced by the fact that from 1946 American foreign policy had set its focus against the Soviet Union (see Cold War ), while in the Soviet-occupied zone it was categorically asserted that all Nazi criminals were exclusively in the West Find. The British had primarily pragmatic intentions for the speedy and smooth reconstruction as possible, and France found it difficult to come to terms with its own past in connection with Marshal Pétain's Vichy government . This half-hearted approach can also be demonstrated for Austria after the collapse of the common regime.

American zone

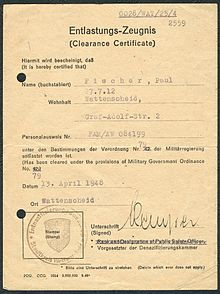

The Americans initially carried out a committed and very bureaucratic denazification in their zone of occupation . The Americans had each adult fill out questionnaires with 131 questions they had created, which enabled a comprehensive definition of the status of mandatory removal . By the end of March 1946, 1.26 out of 1.39 million questionnaires had been evaluated by the Special Branch of the OMGUS authority . The writer Ernst von Salomon addressed this questioning in his autobiographical novel The Questionnaire , published in 1951 .

The future US President Dwight D. Eisenhower , Commander-in-Chief of the American Forces in Germany in 1945, estimated the time it would take to denazify and re-educate democratic ideals to be around 50 years of hard work. US Army General Lucius D. Clay , military governor of the American government in Germany from 1947 to 1949, took the view that the occupation would have to be maintained for at least a generation if the goals set were to be achieved.

On March 5, 1946, the State Council of the American Occupation Area signed the law for the liberation from National Socialism and militarism in the Munich City Hall . With this law, responsibility for denazification and thus also for the internment camps , which were also called denazification camps , in which alleged war criminals, Nazi functionaries and SS members were detained, became the German authorities for Bavaria , Greater Hesse and Württemberg-Baden transfer.

The following groups of people were formed to assess responsibility and to be involved in atonement measures:

- Main culprits ( war criminals )

- Charged / guilty parties ( activists , militarists and beneficiaries)

- Less burdened (probation group)

- Fellow travelers

- Exonerated people who were not affected by the law.

With the Control Council Directive No. 38 of October 12, 1946, these five categories became generally binding for the four zones of occupation.

On May 13, 1946, with the approval of the American military government, the first German lay courts, the Spruchkammern , began to operate to implement the Liberation Act . 545 regionally competent tribunals sat under the supervision of the American military government over more than 900,000 individual cases. However, the American military government had the right to correct German decisions in individual cases.

Among the German politicians, the Wuerttemberg-Baden denazification minister, Gottlob Kamm , was particularly committed to this task. The State Ministry for Special Tasks was founded in Bavaria .

For example, the former party member and comedian Weiß Ferdl was denazified in Munich in October 1946 . He was classified as a fellow traveler and had to pay an atonement of 2000 Reichsmarks . To his relief, he was able to prove that he had already come into conflict with the National Socialist authorities in 1935 and had been warned, and that the Propaganda Minister Goebbels personally asked him to refrain from his “stupid jokes” about the party. He never greeted with " Heil Hitler ".

Under the supervision of the US military government ( OMGUS ), a new policy of re-education was proclaimed from 1947 , the aim of which was to incorporate a still-to-be-created free German state as a western ally. In the course of 1948, the Americans' interest in consistent denazification slackened noticeably, as the Cold War with the Eastern Bloc became more intense. The denazification should now be concluded with a fast track process.

British zone

The British were more moderate than the Americans. Denazification took place here to a very limited extent and was mainly focused on the rapid replacement of the elites .

Here, too, there were exceptions, so the German CEO Günther Quandt could not be charged in Nuremberg because the British did not forward the necessary documents to the investigating American authorities. Although Quandt had demonstrably exploited concentration camp prisoners in his armaments factories (Afa, today VARTA in Hanover, as well as two other companies in Berlin and Vienna) , he was only classified as a 'fellow traveler'. As early as 1946 he received lucrative contracts again - from the British Army.

The British worked with a scale system from 1 to 5. Categories 3 to 5 (lighter cases) were decided by denazification committees that were formed by the British in 1946 from members of local democratic parties such as the SPD. The decisions of these committees were generally accepted since categories 1 and 2 (serious cases) were not dealt with in these committees anyway. German ruling chambers were set up to try members of criminal Nazi organizations such as the SS , the Waffen-SS and the SD . More than 1,200 German judges, prosecutors and auxiliaries carried out a total of 24,200 trials in the British zone.

If one had consistently accused all members of Nazi organizations whose criminal character had been determined by the international military tribunal in Nuremberg, according to American estimates, around 5 million proceedings would have had to be carried out.

A British regulation stipulated that judges and lay judges could not have been members of the NSDAP or any of its organizations. The reason for this was that around 90 percent of the members of the German administration of justice, including the lawyers, were members of the Nazi legal guardian association , whose membership was voluntary. Three quarters of the defendants were given sentences, of which the majority were declared to have been compensated with detention. Only 3.7 percent of the accused had to serve another month in Esterwegen , 4.5 percent still had to pay a fine.

French zone

Since the French occupation force, consisting of units of the Forces françaises libres (Free French Armed Forces) , belonged to the 6th American Army Group as a general staff , the American directives also applied formally to the French military administration. How to deal with former functionaries and collaborators of the Nazi regime, however, was controversial; similar to France itself. "In general, it can be said that the [...] French behaved less strictly and, instead of trying to expose the last possible culprit, concentrated more on the 'worst cases'". Those who were either born on or after January 1, 1919, or who later did not hold an office influenced by the National Socialists, were automatically exonerated. From July 1948 onwards, all “ordinary” party members were classified as followers with ordinance 165.

Christian Mergenthaler , Württemberg Prime Minister until 1945, and more than 800 other former NSDAP functionaries were interned by the French occupying forces in a camp near Balingen and were employed in forced labor in oil shale and cement works. These internees were released by January 1949, mostly as "less burdened". The classification of prominent industrialists from Friedrichshafen was particularly controversial in the French zone: despite protests from socialists and trade unionists, former military economic leaders such as Claude Dornier , Karl Maybach and Hugo Eckener remained largely unmolested because they supplied armaments for France.

Soviet zone

The denazification in the Soviet occupation zone (SBZ) was associated with a fundamental communist restructuring and was carried out quickly and consistently. In some cases, it was already possible to fall back on the preparatory work of the American military authorities, for example in Thuringia and Saxony, where the US Army had arrived before the Red Army.

Officials of the NSDAP and its organizations were removed from offices and some were interned in special camps. Overall supervision of denazification in the Soviet occupation zone lay directly with the Soviet secret service NKVD . It also served the Stalinist rulers as an excuse to pull critics of the new regime, including Social Democrats, out of circulation. Since 1948 the special camps have been under the camp headquarters GULag of the Moscow Interior Ministry. According to official Soviet information, around 122,600 people were imprisoned, plus a further 34,700 of foreign, predominantly Soviet nationality who were foreign or forced laborers in Germany during the Nazi era .

In order to use denazification effectively for the “ political cleansing ” of people who were critical of socialism and to bring the institutions into line, the denazification commissions were made up of one-sided party politicians. They typically consisted of one member of the CDU and LDPD , two representatives of the SED and three representatives of the mass organizations that were also part of the SED.

National Socialist functionaries quickly realized that they had less to fear in the western zones of occupation. Many saw their only chance in offering themselves to the West with anti-communist arguments, which was naturally not possible in the East. Again, the later functionaries of the SBZ were often directly persecuted by the Nazi regime and rated the mere membership in the NSDAP as a crime.

In the camps of the Soviet occupation zone, which until its dissolution in January 1950 were exclusively under Soviet control, there were poor prison conditions, the consequences of which, according to Soviet data, died at least 42,800, according to others, up to 80,000 people. When the camps were dissolved, the inmates were released or handed over to East German authorities to serve further sentences or to convict them - Waldheim trials .

On the part of the SED propaganda, the German Democratic Republic was portrayed as the only anti-fascist state in the post-war period , although in the FRG there was frequent continuity in staffing positions. These allegations were justified, since the twelve-year dictatorship began to be displaced in the West as early as the 1950s, and a qualification for high office was sometimes questioned if a candidate was never a member of the NSDAP. The West replied that the East was also wrongly confronting declared opponents of National Socialism such as Konrad Adenauer and persecuted people like Kurt Schumacher with Nazi charges.

In practice, the SED leadership did not want to forego the cooperation and specialist knowledge of people who were formerly exposed to the Nazi regime, especially since discipline, reliability, organizational talent, speaker talent and obedience were the top priority of secondary virtues in the GDR regime . In the period from 1946 to 1989, for example, of the 263 first and second district and district secretaries of the SED who had been born up to and including 1927 in the districts of Gera, Erfurt and Suhl, almost 14 percent were former NSDAP members, and thus considerably more, than the 8.6 percent of all members who were in the NSDAP according to a survey by the SED from 1954. The issue of the Nazi past of the functionaries was largely concealed in the GDR. In some cases, someone was seduced as a youth. Since it was seen as a problem for the Federal Republic, there was little preoccupation with possible guilt or responsibility.

Public service

The dismissal of NSDAP members from the public service was handled differently in the administrative areas of the Soviet Zone. In some areas only the higher ranks were dismissed, in others all nominal party members were dismissed. The Soviet Zone differed from the Western Zones when it came to filling the largely empty authorities. While they mostly relied on veteran politicians and experts from the democratic spectrum of the Weimar Republic for higher positions, KPD / SED members were preferred in the SBZ. Nevertheless, the war-related shortage of workers in the Soviet occupation zone ensured a pragmatic rehabilitation policy. In August 1947, of the 828,300 statistically recorded NSDAP members, only 1.6 percent were unemployed. However, the NSDAP members in the Soviet Zone were generally not allowed to return to the school service, the police and judicial apparatus and internal administration, while in the western zones they were also allowed to return to these areas, which in some cases became one of many established personal continuity which was perceived as questionable.

In West Germany, the dovetailing of state functions and institutions with party structures after 1945 meant that former SS members were able to exercise their former state functions elsewhere. To be mentioned here are judges, public prosecutors, police officers, doctors, teachers, officers, civil servants, etc. Their specialist knowledge was so important for the development of the Federal Republic that their work for National Socialism after 1945 was deliberately ignored. Back in function, they issued each other clean bill of health, made incriminating documents disappear and bent the law to their advantage. Infected and permeated by the ideology and morality that prevailed between 1933 and 1945 , this elite had a major impact on subsequent generations.

Denazification deadline

The "final denazification law" is the law that was passed by the 1st German Bundestag on April 10, 1951 with only two abstentions, announced on May 13, 1951 and retroactively entered into force on April 1, regulating the legal relationships of those falling under Article 131 of the Basic Law Persons ( BGBl. I p. 307 ). With the exception of groups 1 (main culprits) and 2 (accused), this law now secured the return to the public service. The Bundestag had unanimously passed the "Law to regulate the reparation of National Socialist injustices for members of the public service" just a few days beforehand, as it were for moral compensation; this was announced one day before that ( Federal Law Gazette I p. 291 ).

Comparable laws have also been passed at state level, e.g. For example, in Schleswig-Holstein the “Law to End Denazification”, which was passed on March 14, 1951 with a large majority from all parties. The denazification was finally ended at the state and federal level, and this was accepted by many in the population without contradiction.

Article 139 of the Basic Law , which concerned the legislation enacted for the “liberation of the German people from National Socialism and militarism”, has, according to the prevailing opinion, lost its scope with the conclusion of denazification.

After the statute of limitations for crimes according to § 211 StGB ( murder ) had been lifted in the course of the statute of limitations debate with the 16th Criminal Law Amendment Act of July 16, 1979 ( § 78 Abs. 2 StGB new version), criminal prosecution of Nazi perpetrators is still possible.

After the end of denazification

According to the Final Denazification Act of 1951, renewed or final denazification was requested on various occasions.

When building the Bundeswehr, the military and political leaders were faced with the question of how they should deal with the Nazi past of numerous high-ranking soldiers of the Wehrmacht who have now become soldiers again. → History of the Bundeswehr # Personnel Expert Committee and Nazi Past

In connection with the terrorist group National Socialist Underground , a group called "Denazify Action" also pointed out the unclear role of the constitutional protection authorities in connection with the right-wing extremist series of murders and projected the demand for "denazify" to the Ministry of the Interior and the Chancellery . The action was supported by politicians such as members of the Bundestag Mechthild Rawert , Memet Kılıç , Sevim Dağdelen and Ulla Jelpke as well as artists, journalists and trade unionists.

Implementation in occupied Austria

The Provisional Government passed the Prohibition Act and the War Crimes Act in 1945 after the NSDAP and all of its affiliated organizations had been banned. From a legal point of view, the non-application of the prohibition of retroactive effects in the Prohibition Act or War Crimes Act, according to the teaching of Wilhelm Malaniuk , was important for Austria , with which the Nazi crimes could be prosecuted. Because of these laws, everyone who was a member of this party or one of its organizations such as the SS or SA between 1933 and 1945 had to register. You were not eligible to vote in the National Council election in 1945 .

In a follow-up law of 1946, these people were divided into three groups (war criminals, offenders and offenders). In contrast to Germany, the first group in particular was not brought under the Allied but under Austrian jurisdiction. Only a small number of war criminals were convicted in the Nuremberg trial . The so-called people's courts handed down a total of 43 death sentences (of which 30 were carried out), but also long prison sentences. Of the 137,000 cases examined, 23,000 judgments were pronounced.

Those contaminated in the Allied zones were held by the occupying powers primarily in the two camps, the US camp in the Glasenbach internment camp near Salzburg and the British camp in Wolfsberg in Carinthia. The Soviets mostly left this to the Austrian jurisdiction. Many of them were hired to clean up after war damage.

The followers , as the less burdened were also called, were usually sentenced to fines, dismissals, loss of voting rights or a ban on their profession . Since there were also many skilled workers among these people who were needed for the reconstruction , the two major parties at the time, the ÖVP and the SPÖ , tried to achieve a relaxation of the regulations for fellow travelers among the occupying powers .

The almost 500,000 followers were not eligible to vote in the National Council election in 1945 , but were allowed to vote again in the National Council election on October 9, 1949 . In March 1949 the Association of Independents (VdU), the predecessor party of the FPÖ, was founded .

By amnesties in subsequent years, especially the consequences for the followers were substantially reduced. The people's courts were abolished in 1955 with the State Treaty . The proceedings that were and are later pending under these laws were dealt with by the ordinary jury . The financial collapse ordered in many cases on the occasion of the conviction was reversed in many cases after 1955, as in the cases of the Viennese NS Mayor Hanns Blaschke or the NS Police President of Linz Josef Plakolm .

Hungary

In Hungary between 1945 and March 1, 1948, 39,514 people were investigated, 31,472 proceedings were initiated, 5,954 of which were discontinued, and 9,245 people were acquitted of the charges. Of the 16,273 convictions, 8,041 were imprisonment for less than one year, 6,110 for between one and five years, and 41 people were sentenced to life imprisonment. Of the 322 death sentences, 146 were carried out and the remainder changed to life imprisonment.

Rest of Europe

The denazification in the states of Europe that had been occupied by German troops or allied with the Third Reich resulted largely in settling accounts with the collaborators . The number of judgments against National Socialists is estimated at 50,000 to 60,000.

As part of the liberation of France from the German occupation of France in World War II ( La Liberation ), there were numerous actions between 1944 and 1947 to purge the state apparatus and public life from people who were accused of collaboration. Very often it was about denunciations or the extradition of refugees. First there were the more or less spontaneous, uncontrolled actions ( épuration sauvage ). In addition to abuse and public humiliation, according to various estimates, there were 7,500 to around 10,000 killings. They were not later prosecuted as a crime. In the period that followed, there were forms of purification made justiciable by the Commission d'Épuration ( épuration légale ).

In Italy , the epurazione began at the end of April 1945 , in which (mostly) the partisans for two weeks, uncontrolled by state authorities or the victors' military, exercised their revenge on the fascists. During this time around 20,000 people are said to have been killed, most of them without a court judgment.

Film documents

- 1987: Christina von Braun : The heirs of the swastika . On the history of denazification in both German states

See also

literature

Germany

- Theodor Bergmann : Denazification. In: Historical-Critical Dictionary of Marxism . Volume 3, Argument-Verlag, Hamburg 1997, Sp. 487-491.

- Stefan Botor: The “Berlin Atonement Process” - the last phase of denazification. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-631-54574-6 .

- Niklas Frank : Dark soul, cowardly mouth , Dietz, Bonn, 2016, ISBN 978-3-8012-0405-1 .

- Norbert Frei : Politics of the past. The beginnings of the Federal Republic and the Nazi past. Beck, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-423-30720-X .

- Klaus-Dietmar Henke , Hans Woller (ed.): Political cleansing in Europe. The reckoning with fascism and collaboration after World War II. dtv, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-423-04561-2 .

- Bertold Kamm, Wolfgang Mayer: The Minister of Liberation - Gottlob Kamm and the denazification in Württemberg-Baden. Silberburg, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-87407-655-5 .

- Helmut Kramer : Piggyback into office. Lower Saxony justice under Hitler and afterwards. In: Wolfgang Bittner , Rainer Butenschön, Eckart Spoo (eds.): Before the door swept. New stories from Lower Saxony. Steidl Verlag, Göttingen 1986, ISBN 3-88243-059-1 , pp. 70-76.

- Hanne Leßau: Dealing with one's own Nazi past in the early post-war period. Wallstein Verlag , 2020. ISBN 978-3-8353-3514-1 .

- Peter Longerich : We didn't know anything about it! The Germans and the Persecution of the Jews 1933–1945. Siedler, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-88680-843-2 . (Reviews at perlentaucher.de).

- Kathrin Meyer: Denazification of women: the internment camps of the US zone of Germany 1945–1952 . Metropol, Berlin 2004.

- Lutz Niethammer : The follow-up factory. Denazification using Bavaria as an example. Unchanged new edition. Dietz, Bonn a. a. 1982, ISBN 3-8012-0082-5 .

- Fritz Ostler : The Law for Liberation from National Socialism and Militarism of March 5, 1946 and its implementation. Personal experiences and memories. In: New legal weekly . Vol. 49, No. 13, March 27, 1996, pp. 821-825.

- Dominik Rigoll : State Security in West Germany. From denazification to countering extremists . (= Contributions to the history of the 20th century. Volume 13). Wallstein, Göttingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8353-1076-6 . (also dissertation, Free University Berlin, 2010).

- Armin Schuster: Denazification in Hesse 1945–1954. Politics of the Past in the Post-War Period. (= Publications of the Historical Commission for Nassau. 66; Prehistory and history of parliamentarism in Hesse. 29). Historical Commission for Nassau, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-930221-06-3 . (At the same time: Gießen, Univ., Diss., 1997).

- Clemens Vollnhals (ed.): Denazification. Political cleansing and rehabilitation in the four zones of occupation 1945–1949. dtv, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-423-02962-5 .

- Annette Weinke : The persecution of Nazi perpetrators in divided Germany. Coming to terms with the past 1949–1969 or: a German-German relationship story during the Cold War. Schöningh, Paderborn u. a. 2002, ISBN 3-506-79724-7 . (At the same time: Potsdam, Univ., Diss., 2001).

- Manfred Wille: Denazification in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany 1945-48. Block, Magdeburg 1993, ISBN 3-910173-03-9 .

- Alexander Perry Biddiscombe: The denazification of Germany. A history 1945–1950 . Tempus, Stroud 2007.

Austria

- Dieter Stiefel : Denazification in Austria. Europaverlag, Vienna et al. 1981, ISBN 3-203-50760-9 .

- Peter Goller , Gerhard Oberkofler : University of Innsbruck. Denazification and rehabilitation of Nazi cadres (1945–1950). Bader, Innsbruck 2003, ISBN 3-900372-3 .

- Walter Schuster, Wolfgang Weber (ed.): Denazification in regional comparison: the attempt to take stock (= historical yearbook of the city of Linz 2002 ). Archive of the City of Linz , Linz 2004, ISBN 3-900388-55-5 , online (PDF) in the forum OoeGeschichte.at.

- Margarete Grandner, Gernot Heiss, Oliver Rathkolb (eds.): Future with contaminated sites. The University of Vienna 1945 to 1955 (= cross sections. 19). StudienVerlag, Innsbruck et al. 2005, ISBN 3-7065-4236-6 .

- Maria Mesner (ed.): Denazification between political claim, party competition and the cold war. The example of the SPÖ. Oldenbourg, Vienna et al. 2005, ISBN 3-7029-0534-0 .

- Roman Pfefferle, Hans Pfefferle: Slightly denazified. The professorships of the University of Vienna from 1944 in the post-war years (= writings of the archives of the University of Vienna. 18). Vienna University Press V & R, Vienna 2014, ISBN 978-3-8471-0275-5 .

- Christian H. Stifter: Between spiritual renewal and restoration. American plans for denazification and democratic reorientation of Austrian science 1941–1955. Böhlau, Vienna a. a. 2014, ISBN 978-3-205-79500-1 (also: Vienna, University, dissertation, 2012).

Contemporary representations

- James F. Tent (Ed.): Academic proconsul. Harvard sociologist Edward Y. Hartshorne and the reopening of German universities. His personal account . Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, Trier 1998 (see: Edward Hartshorne ).

- Harold Zink : The United States in Germany, 1944–1955 . Van Nostrand, Princeton 1957.

- Harold Zink: The American denazification program in Germany. In: Journal of Central European Affairs. Oct. 1946, pp. 227-240.

Fiction

- Ernst von Salomon : The questionnaire . Rowohlt, Hamburg 1951 (18th edition. 2007, ISBN 978-3-499-10419-0 ).

Web links

- Literature on the subject of "denazification" in the catalog of the German National Library

- Entnazifikation.at : Knowledge portal about denazification in Austria

- Paul Hoser: Denazification . In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria

- Law No. 104 for Liberation from National Socialism and Militarism of March 5, 1946

- Introduction to the use of denazification files: Spruchkammer files in the Baden-Württemberg State Archives (Ludwigsburg State Archives) .

- Concrete example of denazification: The denazification in Wasserburg / Inn using the example of the war group leader Kurt Knappe . (PDF; 321 kB)

- James L. Payne: Did the United States Create Democracy in Germany? . In: The Independent. Review, Volume 11 Number 2, Fall 2006 (English)

- Questionnaire from Hugo Eckener's denazification files as a digital reproduction ( files 1 and 2 ) in the online offer of the Sigmaringen State Archives

- Andreas Eichmüller: The prosecution of Nazi crimes by West German judicial authorities since 1945. A balance sheet. (PDF) In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte . 2008, pp. 621-640.

Single receipts

- ↑ Denazification (PDF) Scientific Services of the German Bundestag , elaboration of September 27, 2011, p. 5 f.

- ↑ Uta Gerhardt, Gösta Gantner: Ritual process denazification - a thesis on the social transformation of the post-war period. In: Forum ritual dynamics. Contributions to the discussion of the SFB 619 “Ritual Dynamics” of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg. No. 7 / July 2004, p. 7.

- ↑ Control Council Directive No. 24. Removal of National Socialists and persons who are hostile to the efforts of the Allies from offices and positions of responsibility ( Memento of August 17, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) of January 12, 1946. Verassungen.de, accessed on May 17, 2018 . August 2018.

- ^ Armin Nolzen : The NSDAP before and after 1933 bpb , November 10, 2008.

- ↑ a b Dieter Schenk: Blind in the right eye. Cologne 2001.

- ^ A b Manfred Görtemaker: History of the Federal Republic of Germany. Fischer 2004.

- ↑ Example of rat line north ; see. Flensburg comrades . In: Die Zeit , No. 6/2013.

- ↑ Wave of Truths . In: Der Spiegel . No. 1 , 2012 ( online ).

- ^ Archive of the City of Linz 2004: Denazification in a regional comparison ( Memento of December 8, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 80 kB).

- ^ OMGUS: Monthly Report of the Military Governor for March 1946. Institute for Contemporary History, MA 560.

- ^ Norgaard, Noland: Eisenhower Claims 50 Years Needed to Re-Educate Nazis. In: The Oregon Statesman. October 13, 1945, p. 2, accessed November 19, 2014.

- ↑ Eric Friedler: A German Dynasty, the Nazis and the KZ. ARD documentation (Quandt's denazification).

- ^ Heiner Wember: re-education in the camp. Internment and punishment of National Socialists in the British zone of occupation in Germany. (= Düsseldorf writings on the modern history of North Rhine-Westphalia. Volume 30). Essen 1991, ISBN 3-88474-152-7 , p. 276 ff.

- ↑ Clemens Vollnhals: Denazification. P. 34 ff.

- ↑ Jonathan Carr: The Wagner Clan. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-455-50079-0 , p. 336 f.

- ↑ Martin Ebner: The denazification of Zeppelin, Maybach, Dornier & Co. case study on the city of Friedrichshafen.

- ↑ See also Helga A. Welsh: Revolutionary change on command? Denazification and personnel policy in Thuringia and Saxony (1945–1948) (= series of quarterly journals for contemporary history . Volume 58). Oldenbourg, Munich 1989.

- ↑ see also Alexander Sperk: Denazification and personnel policy in the Soviet occupation zone Köthen / Anhalt. A comparative study (1945–1948). Verlag Janos Stekovics , Dößel 2003, ISBN 3-89923-027-2 .

- ↑ Bodo Ritscher : The Special Camp No. 2 1945–1950. Catalog for the permanent historical exhibition. Wallstein Verlag, 1999, ISBN 3-89244-284-3 .

- ^ Damian van Melis: Denazification in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania: Rule and Administration 1945–1948. 1999, ISBN 3-486-56390-4 , p. 208.

- ↑ Ralph Giordano The Second Guilt . Cologne 2000.

- ^ Clemens Vollnhals: Denazification, political cleansing under Allied rule. In: End of the Third Reich - End of the Second World War. Munich 1995, ISBN 3-492-12056-3 , p. 377.

- ^ Stefan Wolle : The great plan - everyday life and rule in the GDR 1949–1961 , Christoph Links Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-86153-738-0 , pp. 205–207.

- ^ Stefan Wolle: The big plan - everyday life and rule in the GDR 1949–1961. Christoph Links Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-86153-738-0 , pp. 207 f .; the numbers according to wool at Sandra Meenzen: Consistent anti-fascism? Thuringian SED secretaries with an NSDAP past . State Center for Civic Education Thuringia, Erfurt 2011, ISBN 978-3-937967-82-0 .

- ^ Clemens Vollnhals: Denazification, political cleansing under Allied rule. 1995, p. 383 ff.

- ↑ cf. Heiko Buschke: German press, right-wing extremism and the National Socialist past in the Adenauer era. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-593-37344-0 , p. 64 ff. ( Excerpt from google books )

- ↑ Plenary Minutes, p. 5110 (PDF)

- ↑ Klaus-Detlev Godau-Schüttke: From denazification to renazification of the judiciary in West Germany. In: forum historiae iuris. June 6, 2001 (online)

- ↑ cf. BVerfG, decision of September 27, 1951 - 1 BvR 70/51

- ↑ BGBl. I p. 1046

- ↑ see Bert-Oliver Manig: The politics of honor: the rehabilitation of professional soldiers in the early Federal Republic (= publications of the contemporary history working group Lower Saxony. Volume 22). Wallstein-Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-89244-658-X . Reading sample

- ↑ Daniel Bax: Iridescent anger. In: the daily newspaper , February 23, 2012.

- ↑ DENACIFY Germany. In: migazin , February 27, 2012.

- ↑ Constitutional Act of May 8, 1945 on the prohibition of the NSDAP (Prohibition Act), StGBl. No. 13/1945

- ↑ Constitutional Act of June 26, 1945 on War Crimes and Other National Socialist Atrocities (War Criminal Law), StGBl. No. 32/1945

-

^ Claudia Kuretsidis-Haider: The reception of Nazi trials in Austria by the media, politics and society in the first post-war decade. In: Jörg Osterloh (Hrsg.): Nazi trials and the German public. Occupation, early Federal Republic and GDR. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-525-36921-0 , p. 415.

Claudia Kuretsidis-Haider: The people are in court. Austrian justice and Nazi crimes using the example of the Engerau trials 1945–1954. Studies-Verlag, Innsbruck / Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-7065-4126-2 , p. 55 ff.

Wilhelm Malaniuk: Textbook of criminal law. Volume ?, p. 113 and 385. - ^ Trials: People's courts on nachkriegsjustiz.at, accessed on February 27, 2019.

- ^ Wolfgang Graf: Austrian SS Generals. Himmler's reliable vassals. Hermagoras-Verlag, Klagenfurt / Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-7086-0578-4 , pp. 154 and 327.

- ↑ Randolph L. Braham : The politics of genocide. The Holocaust in Hungary. 2 vol., Columbia University Press, New York 1981, ISBN 0-231-05208-1 , pp. 1167 f.

- ↑ Fritz Molden : The Austrians or the power of history. Vienna 1986, p. 287.

- ^ Review , Deutschlandfunk