Church and State

The relationship between church and state is a special case of the relationship between religion and politics , which has strongly determined the history of Europe .

Christian theology has repeatedly reflected on this relationship and developed and modified various state theories with political effects. The centuries-long cultural dominance of Christianity was only gradually pushed back from the Age of Enlightenment . Since the French Revolution there has been a separation of church and state in various forms and an ideologically neutral constitutional state . Along with universal human rights , this also protects individual freedom of belief and freedom of church organization. As a result, the church state teachings have also reoriented themselves.

In many non-European countries where churches exist, their activities are subject to severe restrictions: even where freedom of religion is theoretically represented. In others, they continue to play a major role in influencing the state.

overview

The relationship of the church to the state and the state to the church has always depended on the respective power relations and the respective leading world views . The epochs of this conflict-ridden relationship in Europe are reflected in the respective teachings of the church on the nature and tasks of state and church, alongside which, since the Renaissance, increasingly autonomous state philosophies have appeared. They can be assigned to a few main models, which historically were not ideally shaped, but with numerous shades and links:

- Church sees itself as an eschatological salvation community, which distances itself from all worldly power and waits suffering for its end: the time of the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire

- Church sees itself as a state church , which Christian rulers also direct in matters of faith: Caesaropapism since the Constantinian change in late antiquity

- Church sees itself as the unifying spiritual power of the state, determines its worldview and also its politics: superiority of the sacerdotium (literally: priesthood; here: spiritual power of the papal church) over the regnum or empire (the secular power ) up to the claim of the papacy on world domination in the High Middle Ages

- The church sees itself as a spiritual counterpart to the secular authorities , who save souls and bind consciences, but who do not want to have their own jurisdiction and power: Reformation

- The state sees itself as a sovereign community of convenience encompassing all citizens, which does not tolerate any special rights and therefore either also determines the religion of its citizens ( cuius regio, eius religio in regional and state churches and absolutism ) or religion only as a private matter, churches only as religious associations and strictly separates it from the state ( Enlightenment , French Revolution ).

- The state sees itself as a totalitarian worldview state and strives for legal and propaganda purposes to disempower and dissolve all religious and ideological autonomy ( National Socialism and Stalinism ).

- The state sees itself as a democratic constitutional state based on an indefinable constitutional order , which precedes the inalienable human rights of all politics and therefore allows and protects various religions within the framework of civil order. The church sees itself as a religious community that determines its own order in accordance with its respective creeds and, under certain circumstances, claims a right of resistance to totalitarian tendencies .

Biblical roots

Hebrew Bible

The Tanach , the Hebrew Bible , as a collection of religious writings that have grown over 1200 years does not contain a uniformly formulated theory of the state. Because the people of Israel understood their legal order, the Torah , as a revelation of YHWH , they could only conceive their political orders as an answer to the will of God received in the commandments . The history of Israel has developed various forms of government, which in the Tanach are theologically assessed differently.

- Early Israel was a loose tribal union without superordinate state structures that saw itself as a direct theocracy . His cohesion was guaranteed in the case of external threats by charismatic "judges" (military leaders).

- It later became a kingship analogous to ancient monarchies . Biblical historiography judges this change as “falling away” from God (1 Sam 8,7). Nevertheless, the king owes his office to divine election (1 Sam 9:17). Above all, it had a protective function in foreign policy and, instead of the spontaneous situational calling of individuals, soon formed dynasties . Biblical theology also adopted elements of the ancient ideology of the god the king and raised the king to the position of mediator of salvation: just as God confirms his hereditary succession to the throne, the king, as patron of the temple cult (i.e. the practice of religion) guarantees the salvation of the people (2 Sam 7: 13f). This is where the idea of “divine grace” comes from, which has been the dominant form of legitimation in Europe since Charlemagne .

- The prophecy in the Tanakh accompanied kingship extremely critically from the beginning. King David almost lost God's grace for his murder of Uriah . Above all, the kings of the northern empire , but also of the southern empire , were often “rejected” as idolaters: defeat in foreign policy or internal political turmoil were considered God's “judgment” for breaking the social laws of the Torah and failing the poor and the weak. B. Amos and Hosea in the 8th century.

- The catastrophe of the temple destruction and exile in 586 BC Chr. Was processed in the Babylonian exile with a religious-historical unique future expectation: the ideal image of the Messiah and just judge (e.g. in Isa 9 and 11) and the vision of the final judgment (e.g. in Dan 7: 2-14) expresses the hope for an end to all human tyranny and worldwide peace among nations .

New Testament

Few texts in the New Testament (NT) deal with the phenomenon of the state. Because Jesus of Nazareth proclaimed the near kingdom of God as the end of all man-made systems of rule. Because this empire limits all political power, he taught renunciation of violent rebellion against the state, but at the same time a fundamentally different, domination-free behavior among Christians: You know that the rulers of the world do violence to their peoples - it should not be like that among you ! (Mk 10.42) His statement on the tax question - give the emperor what is the emperor's, but God what is God (Mk 12.17) - rejects any deification of human power and commands its submission to God's will.

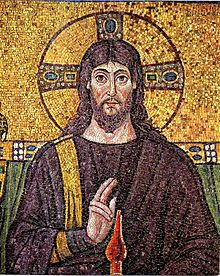

The early Christians proclaimed death and resurrection of the Son of God and of all state power is an absolute limit was set accordingly as eschatological reversal which anticipated the coming judgment of the world already. So Christ may be Lord over all masters of this passing world. By believing in him, all worldly rulers are already subordinate to his invisible rule.

According to Acts 5:29, Simon Peter emphasized the primacy of God's will over all human claims to power: One should obey God more than people. Paul of Tarsus saw worldly rulers not only in the target state, but in the actual state as “servants of God” to whom one had to subordinate oneself “for the sake of conscience”, since God had appointed them to protect justice. So he exhorted Christians to pay Roman taxes. Yet he did not see the state as an instrument of God per se . Roman state officials who persecuted Jews and Christians can be roused through solidarity-based good deeds : The Christian community should visibly resist the blasphemous way of life of the Roman upper class in anticipation of the near final judgment ( Romans 12-13).

Against the background of the persecution of Christians , the Apocalypse of John placed the expectation of the "new Jerusalem" (Rev 21), i.e. a coming, immediate theocracy, against the Roman tyranny, which was to be spiritually disempowered as an "animal from the sea" (Rev 13): If " God will be all in all “, earthly power will no longer be necessary to organize coexistence.

Nonetheless, the intercession for the governments (1 Petr 2,13ff; 1 Tim 2,1–4) was an expression of fundamental Christian acceptance of the state monopoly of power and loyalty to the respective rulers.

Catholic state teaching

After Emperor Theodosius I declared Christianity to be the state religion of the Roman Empire in 380 with the Edict of the Three Emperors , Augustine drafted an ecclesiastical state theory in his work De civitate Dei (around 420). Their basic ideas remained predominant throughout the Middle Ages .

The “state of God” ( civitas Dei = Catholic Church) stands in permanent contrast to the earthly state ( civitas terrena = Roman power state). The latter represents the Satanic kingdom of the world ruled by sin , the communio malorum (community of the wicked). Their necessary corrective is the communio sanctorum (communion of saints ) called by divine grace . This church is an ideal corpus (body) of Christ , i.e. an image of the rulership of Christ. But since sin continues to work in it, it is really a corpus mixtum, just as the state does not embody evil in its pure form. The political order always requires ecclesiastical guidance and limitation in order to assert the all-encompassing claims of the Catholic faith. On the other hand, it should create external peace in order to preserve the conditions for the salvation of all citizens. A state that also strives for and protects their spiritual well-being itself tends to become more and more a corpus Christianum .

This interrelated confrontation between church and state aimed at the gradual realization of a Christian policy under church leadership. It was supposed to remove the ground from the Roman state ideology, which until then had used the pagan belief in gods to maintain the empire. It presupposed the Church's claim to political world domination, in which the later tension between the papal sacerdotium and the imperial regnum was already laid out.

Thomas Aquinas traced the state back more clearly than Augustine not only to the fall of man, but to the natural law (lex naturalis) that can be found in the still good creation . In doing so he formulated a natural theology based on Aristotle : Since the cosmos is ordered to its Creator as the first cause ( prima causa ) , reason, not belief , can already recognize the ultimate goal of all things. Accordingly, no inner-worldly politics has its ultimate goal in itself, but is a preliminary stage to the transcendent goal of redemption ( Summa theologica ) . But the church does not exercise any direct world domination in this draft state, but only guides politics towards recognizing its own purposes. The state is responsible for the common good (bonum communis) and the maintenance of external peace (De regimine principum) . The supernatural belief in Jesus Christ supplements and exaggerates the natural knowledge of reason and provides guidelines for an unchangeable order of salvation (ordo salutis) that can allow various forms of government.

Protestant state teaching

Like Augustine, Martin Luther emphasized the distinction between the realms of God and the world. He saw church and state as two “regiments” of God with different tasks: the church preaches and distributes the forgiveness of sins without worldly power, the state defends evil, if necessary with force. Both thus curb the rule of evil on earth until the arrival of the immediate rule of God, but as part of the world they are also permeated by evil.

The separation of church and state was a major concern for the free churches . The Baptist Thomas Helwys published the book A Short Declaration of the Mystery of Iniquity in 1612 and called for freedom of religion for everyone.

Because the sovereigns carried out the Reformation and determined the denomination of their subjects ( cuius regio, eius religio ), a new close alliance of throne and altar arose in the Protestant countries. Conservative Lutheranism legitimized all government as an authoritarian position of God (Romans 13, 1–4) and did not define it as an image of the rule of Christ, but as a "creation order", ie a structure that is necessary in nature. A critical limitation or even democratization of state power always met with resistance from the Lutheran Orthodox regional churches. Even after the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, their theology continued to legitimize monarchy and feudalism , supported the class state and shaped Christian “submissive obedience”.

A typical representative for this was the constitutional and canon lawyer Friedrich Julius Stahl (1802–1861). His Philosophy of Law (Heidelberg 1830–37) saw autonomy and popular sovereignty as opposed to the “Christian state”: only this would recognize a divine order, the constitutional monarchy could best guarantee this. However, this must represent the people in accordance with the constitution and guarantee certain freedoms. Stahl tried to take up liberal ideas and incorporate them into his reform conservatism. To this end, he founded and led the Conservative Party of Prussia during the Restoration from 1848 to 1858 and determined its program.

Pietism and the Enlightenment, on the other hand, moved the creed into the private sphere. Christian social ethics was largely limited to " inner mission " and diakonia , so it hardly acted as a critical corrective of state policy in the field of liberal theology.

After the First World War , Karl Barth's commentary on the Romans 1919 reveals that God's unavailable kingdom radically calls into question all state authority. The state that God “orders” (Rom. 13: 1) is never identical with rulers and state systems, but their constant “crisis”, which deprives them of any unauthorized legitimation. State systems could neither be reformed nor revolutionized, but only confronted with doing the good that defies the immanent logic of obedience and resistance.

The Barmer Declaration formulated by Barth in 1934 proclaimed the "kingship of Jesus Christ" over all areas of the world against the Lutheran doctrine of the two kingdoms . From there it determines the purpose of the state (thesis V):

"The state has the task of ensuring law and peace in the as yet unredeemed world under the threat and use of violence."

This theologically based commitment to the rule of law and peace policy contradicted the totalitarian state model of fascism . In Justification and Law (1938), Barth derived the church's right of resistance against the total state from the positive relationship between God's unconditional grace (Christ rule) and human rights that bind the state. In 1963 he added the Barmer thesis V as a contradiction to the means of mass destruction with the addition:

"The state has the task of ensuring justice and peace in the not yet redeemed world in which the church also stands - if necessary under threat and exercise of force."

The EKD's memorandum of democracy from 1985 wanted to learn from the failure of Protestantism against the Nazi state and now officially recognized the social and liberal constitutional state. The state should "keep the effects of human error within limits" (conservative motive). At the same time she stated (reform motive):

"In the light of the coming righteousness of God, every human legal and state order is provisional and in need of improvement."

Throne and altar

“Throne and Altar” was a formula of the French clergy of the Ancien Régime (“le trône et l'autel”) referring to the sacred roots of the monarchy . In Prussia the restoration it was raised one the state supporting anti-revolutionary thinking to the solution. Since the 1830s ( Heinrich Heine ) the formula changed into the polemical catchphrase of liberalism and socialism against the alliance of monarchy and state church that characterizes the monarchical authoritarian state .

Legal

The state and religious communities have often tried to regulate rights and obligations among themselves through legal acts (e.g. contracts). This area of law is called state church law or religious constitutional law. It is the part of the state constitutional law that regulates the state's relations with the churches and other religious communities.

One example is a decree passed by the French National Assembly in 1789 (“Le décret des biens du clergé mis à la disposition de la Nation est un décret pris le 2 novembre 1789”), which u. a. regulated the nationalization of church property and the payment of priests as civil servants.

See also

literature

- Hans Barion et al. a .: Church and State . In: Religion Past and Present . Volume 3 (1959). 3rd edition, col. 1327-1339.

- Robert M. Grant, Peter Moraw et al. a .: Church and State . In: Theological Real Encyclopedia . Volume 18 (1989), pp. 354-405.

- Albrecht Hartel: Separate ways. Measures to separate state and religion . Norderstedt 2011, ISBN 978-3-8423-3685-8 .

- Reinhold Zippelius: State and Church. A story from antiquity to the present . 2nd edition, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-16-150016-9

Individual evidence

- ↑ https://www.etudier.com/dissertations/Le-Trône-Et-l'Autel-1815/99778.html

- ^ Paul Fabianek: Consequences of secularization for the monasteries in the Rhineland: Using the example of the monasteries Schwarzenbroich and Kornelimünster. BoD Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-8482-1795-3 , p. 6 and annex ( Le décret des biens du clergé mis à la disposition de la Nation of 1789).