Teschen dialects

The Teschener dialects ( Czech těšínská nářečí , Polish gwara cieszyńska , also narzecze cieszyńskie , locally po naszymu , German about "in our [language]") are a dialect continuum on both sides of the Olsa in Teschen Silesia in Poland and the Czech Republic ( Olsa region ).

The dialect's roots come mainly from Old Polish (the phonology and morphology is consistently Polish), but its diachronic development gave it a transitional nature.

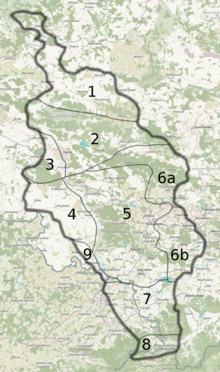

Stanisław Bąk (1974), Alfred Zaręba (1988) and Bogusław Wyderka (2010) divided the Polish-Silesian dialects in Cieszyn Silesia into two groups ( Cieszians and Jablunkauers ). Sometimes the Freistädter (Czech. Fryštát, pln. Frysztat, locally Frysztot) group was differentiated. Nowadays, everyone speaks Standard Polish in Poland and Standard Czech in the Czech Republic , but the Teschen dialects remained the main language of the Polish minority in the Czech Republic.

The Cieszyn Silesian dialect are the Upper Silesian closest less the Malopolska and Lašsko dialects (especially Oberostrauer dialect on the eastern bank of the Ostravice ) between Opava and Ostrava . Occasionally these dialects, especially from the 1950s to the 1990s, are referred to as Eastern Lachish, this term was used by the Moravian linguist Ad. Waiter in the 1940s for political reasons.

history

The first traces of the language of the local population come from documented mentions of place names in Latin-language documents. At that time, the old forms of the Polish and Czech languages were much closer to each other than they are today, but the nasal vowels present in these names help categorize this language form into the Lechic languages , not the Czech-Slovak dialects. The second linguistic characteristic that can best be recognized in ancient sources, which distinguishes the old Teschen dialects from the Moravian Lachish languages , is the lack of spirantization g ≥ h (in Teschen dialects g was retained).

After 1430, especially 1450, the Czech official language almost completely replaced the previous official languages Latin and German (except in Bielitz ) in the Duchy of Teschen. These numerous documents led some Czechoslovak linguists around the middle of the 20th century to the conclusion that the area was originally Czech and was only Polonized later, at the earliest in the 17th century. The Polish researchers, on the other hand, ensure that z. B. the nasal vowels remained uninterrupted in the place names in the simultaneous German-language and ecclesiastical Latin documents. Although the ducal chancellery remained Czech-speaking even after 1620 , longer than in Bohemia itself, the documents increasingly written by the local population from the 16th century onwards were often only apparently written in the official language. An invoice from a locksmith from Freistadt in 1589 contained so many “errors” that it was referred to in Polish literature as the first Polish document from Cieszyn Silesia. Shortly afterwards, Johann Tilgner, a self-proclaimed German from Breslau, settled in the Duchy of Teschen. Having learned the Moravian language, he came to be the overseer of the Skotschau-Schwarzwasser estate under Duke Adam Wenzel . In his diary under the title Skotschau Memories , however, he described how he learned the Polish language from the local population. In the second half of the 17th century, this language was named in the reports of the episcopal visitations from Wroclaw concio Polonica (conc + cieō - “summoned”, or the language of the sermon). The linguistic boundary to the concio Moravica did not coincide with the boundary of the deaneries and was similar to the boundary in the middle of the 19th century. The spoken Polish-Silesian language later seeped through, especially in the diaries or quasi-official chronicles of the village scribes. One of the most famous examples was written by Jura (Jerzy, Georg) Gajdzica (1777–1840) from Cisownica . The text in the local dialect has been stylistically adapted to the Polish literary language:

“Roku 1812 przed Gody Francuz prziszeł na Mozgola do bitki, ale they Francuzowi źle podarziło, Pon Bóg mu tam bardzo wybił, trefiła zima wielko i mroz, i zmorz tam, że sie go małico wrje chóciło i poćieł Galico wrje chóciło i mus. (...) "

Depending on the training of the scribe, different levels of code-switching between Czech, Moravian, Silesian and Polish were observed, which obviously did not prevent communication between Slavs, in contrast to the language barrier that often existed in reality between Slavs and Germans.

After the First Silesian War , the area was separated from the rest of Silesia by the Austro-Prussian border. The Upper Silesian dialect, previously under comparable influence of the Czech official language, increasingly came under the influence of the German language, especially after 1749, and was described somewhat pejoratively in German water-Polish . This phenomenon was noticeably delayed on the Austrian side of the border. In 1783, the Teschner district was attached to the Moravian-Silesian Provincial Government with its seat in Brno and the Moravian-language textbooks were used in the elementary schools , despite z. B. the protests of Leopold Szersznik , the overseer of the Roman Catholic schools in the district. Reginald Kneifl , the author of the topography of the kk share in Silesia from the early 19th century, on the other hand, used the term Polish-Silesian (more rarely Polish and water Polish) for the majority of the localities in the region. However, the term water Polish was also used later by Austrians in the 19th century, e.g. B. by Karl von Czoernig-Czernhausen .

In 1848 Austrian Silesia regained administrative independence. Paweł Stalmach initiated the Polish national movement by publishing the Polish weekly Tygodnik Cieszyński , the first newspaper in Cieszyn Silesia, although the majority of the water Polaks remained indifferent nationally for several decades. In 1860, at the suggestion of Johann Demels , the long-time mayor of Teschen, the Polish and Czech languages became the auxiliary languages of the Crown Land. This led to the unhindered development of the Polish language in authorities and elementary schools for the first time in the history of the area. The middle schools remained exclusively German-speaking. 1874 beat Andrzej Cinciała in the Imperial Council the opening of a Polish teacher seminar in Cieszyn and a Czech in Opava before. This was strongly contradicted by Eduard Suess because, according to him, the local language was not used in books but Polish, a mixture of Polish and Czech . During this time the level of prestige of the German language in Cieszyn Silesia was at its peak. The percentage of German-speaking residents in small towns such as Skotschau and Schwarzwasser rose to over 50% by the early 20th century. This accelerated the process of borrowing from German in the Teschen dialects, also in the villages. The counterweight to the Polish national movement has always been the so-called Schlonsak movement, especially widespread among the Lutherans around Skotschau. It was always supported by local German liberals (e.g. in the form of the newspaper “Nowy Czas” founded by Theodor Karl Haase in 1877) and was benevolent towards the parallel significance of the German language. Józef Kożdoń , the leader of the Silesian People's Party founded in 1909, never denied that the Teschen dialects were a dialect of the Polish language, but compared the situation in the region with Switzerland , where the German dialects did not make Germans out of Swiss and, analogously, the Silesians were not Poles. A national conflict also flared up between Poles and Czechs in the early 20th century, culminating in the Polish-Czechoslovak border war in 1919. Petr Bezruč popularized the theory of the Polonized Moravians in the Silesian Songs, and the Czech activists claimed at the time that the Moravian language was actually more understandable than the Polish literary language for the local Silesians.

On June 25, 1920, the Council of Ambassadors of the victorious powers determined the course of the border without holding a referendum. This separated the dialect area between Poland and Czechoslovakia. On the Polish side, due to the greater linguistic affinity, they were getting closer and closer to the standard Polish language, but some new influences of the Upper Silesian dialect were also observed (e.g. partial displacement of the word fajka , English cigarette , by the Upper Silesian cygaretla ) , while on the Czechoslovak or Czech side the dialects came more and more under the influence of the Czech language, mainly for syntax and lexicon z. For example, many new loans from the Czech Republic were used, which are unknown in Poland. In general, however, the Teschen dialects are better preserved on the Czech side than in Poland, especially as the main everyday language of the regional Polish minority, often used in public offices or in conversations with doctors or teachers.

It was not until 1974 that Stanisław Bąk defined the Teschen dialect as a separate sub-dialect. This was followed by Alfred Zaręba (Zaremba, 1988) and Bogusław Wyderka (2010). In the 1990s the debate about the independence of the proposed Silesian language began. In Upper Silesia there have been many efforts to standardize the language, including z. B. new alphabets that also included the Teschen dialects (see e.g. the Silesian Wikipedia ). This movement is much weaker in Cieszyn Silesia, both on the Polish and the Czech side. The use of the Polish spelling or the alphabet was a. long established by Adolf Fierla, Paweł Kubisz, Jerzy Rucki, Władysław Młynek, Józef Ondrusz, Karol Piegza, Adam Wawrosz and Aniela Kupiec, who viewed their works as part of Polish tradition. On the Czech side, however, the dialect was increasingly written in the Czech spelling (example: poczkej na mie [wait for me] in Polish vs. počkej na mě in Czech). Czech linguists in recent decades abandoned the classification of the dialects in the Olsa area as East Lasian , but continued research independently of the dialects in Poland and more often they emphasized their mixed Polish-Czech character , suggesting that they belong to both languages at the same time, and unite all nationalities in the Olsa area.

Differences from surrounding languages

Czech

- Regression of nasal vowels (mostly broken down), e.g. B. dómb / kónsek "oak / piece" vs. Polish dąb / kąsek and Czech dub , rarely in a rudimentary form as in kousek ; in the oldest sources they were u. a. as -am-, -an and followed the documentary development in the rest of Poland, e.g. B. on // om> un // um and ę // em> ym // im, but were later split up in contrast to standard Polish.

- Preservation of the consonant g (ch. H , less often k ),

- Presence of the soft consonants ś , ź , ć , dź ,

- Preservation of the consonant dz

- Vowel ó , as the result of the development o > ó and e > é > y ,

- Consonant ł , documented with the development ł > u ,

- Different scope of dispalatalization (see also siakanie ) and palatalization in groups n , p , b , v ... + e ,

- Polish vowel letters ,

- Absence of Czech vowel lulling ,

- Polish development of the groups * tort and * tolt ,

- Absence of the Czech change šč > šť ,

- Other development of the sonants r and l ,

- Stress on the panultima , as in the Polish language;

- all vowels are short, as in the Polish language,

- Iterativa in -ować (in the written Czech language -ávat ).

Slovak

- the sound rz / ř .

Upper Silesian

- Range of vowels,

- Other inflection , e.g. B. idym spatki przez tóm wode (I go back through the water) vs. Oberschles. ida (m) nazod bez ta woda

- Vocabulary, less German and more Czech borrowings (e.g. spatki - back, czech zpátky ).

Some special features

morphology

- Iteratives on -ować , e.g. B. słychować-słychujym (I use to listen), in the written Czech language with a fixed infix slýchávat-slýchávám .

syntax

- partially non-congruent possessive perfect , e.g. B. my tam mieli nojynte takóm małóm kuczym (we had rented a small house there),

- finite verb tends to be in the second position (in the main clause), other parts of the predicate at the end of the sentence, e.g. B. yoke był uż downo przijdzóny (I had come a long time ago),

- Final position of the finite verb in the subordinate clause, e.g. B. yoke myślała, że ón padńóny je (I thought he had fallen),

- pleonastic pronoun in the (contextual) subject, e.g. B. ón owčoř ńechćoł odynść / ón owczorz niechciół odyńść (the shepherd did not want to leave),

- formal subject of impersonal sentences, e.g. B. óno to nima taki proste (it's not that easy),

- Perfectly intransitive verbs with PPP, e.g. B. śiostra je už póńdzóno / siostra je uż póńdzióno (the sister has already left).

vocabulary

- many similarities with the Lachish dialects of Czech.

- The numerous loanwords from the German language come predominantly from the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Text example

"Hladoł jo to miejsco dość długo. Na kóniec jo prziszoł wczasi. Tam jo se też zeznómił ze Zuzanóm. Prawie my chcieli iść hore, jak zaźnioł hróm. "

German:

“I looked for the place for a long time. In the end I came earlier. It was there that I met Susanne. We were just about to go up when a thunder rumbled .. "

Polish dialect (Silesian):

"Szukołch tyn plac dojś dugo, yntlich prziszołch wcześni, tam żech sie poznoł ze Zuzom, prawie chcieli my iś na góra, jak doł sie s ł ysze ć grzmot .."

Polish:

“Szukałem tego miejsca dość długo, w końcu przyszedłem wcześniej. Tam poznałem Zuzannę, chcieliśmy właśnie iść na górę, kiedy zagrzmiał grom .. "

Czech:

“Hledal jsem to místo dost dlouho. Nakonec jsem přišel dříve. Tam jsem se též seznámil se Zuzanou. Právě jsme chtěli jít nahoru, když uhodil hrom .. "

literature

- Zbigniew Greń: Śląsk Cieszyński. Dziedzictwo językowe . Towarzystwo Naukowe Warszawskie. Instytut Slawistyki Polskiej Akademii Nauk , Warszawa 2000, ISBN 83-8661909-0 (Polish).

- Kevin Hannan: Borders of Language and Identity in Teschen Silesia . Peter Lang, New York 1996, ISBN 0-8204-3365-9 (English).

- Jadwiga Wronicz (inter alia): Słownik gwarowy Śląska Cieszyńskiego. Wydanie drugie, poprawione i rozszerzone . Galeria "Na Gojach", Ustroń 2010, ISBN 978-83-60551-28-8 .

- Robert Mrózek: Nazwy miejscowe dawnego Śląska Cieszyńskiego . Uniwersytet Śląski w Katowicach , 1984, ISSN 0208-6336 , p. 58 (Polish).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hannan 1996, p. 129

- ↑ Hannan 1996, p. 191

- ↑ Izabela Winiarska: Zasięg terytorialny i podziały dialektu śląskiego .

- ↑ Piotr Rybka, Gwarowa wymowa mieszkańców Górnego Śląska w ujęciu akustycznym , Katowice, 2017, pp. 56–60.

- ↑ K. Hannan, 1996, p. 162

- ↑ a b January Kajfosz: Magic in the Social Construction of the Past: the Case of Cieszyn Silesia , p 357, 2013;

- ↑ a b Jaromír Bělič: Východolašská nářečí , 1949 (Czech)

- ↑ R. Mrózek, 1984, p. 306.

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, p. 51

- ↑ Idzi Panic: Śląsk Cieszyński w początkach czasów nowożytnych (1528-1653) [History of the Duchy of Teschen at the beginning of modern times (1528-1653)] . Starostwo Powiatowe w Cieszynie, Cieszyn 2011, ISBN 978-83-926929-1-1 , p. 181-196 (Polish).

- ↑ Słownik gwarowy, 2010, pp. 14–15

- ↑ J. Wantuła, Najstarszy chłopski bookplate polski , Kraków, 1956

- ↑ J. Wronicz, Język rękopisu pamiętnika Gajdzicy , 1975

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, p. 39.

- ↑ a b Z. Greń, 2000, p. 33

- ↑ Janusz Spyra: Śląsk Cieszyński w okresie 1653–1848 . Starostwo Powiatowe w Cieszynie, Cieszyn 2012, p. 361, ISBN 978-83-935147-1-7 (Polish).

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, p. 34

- ↑ Janusz Gruchała, Krzysztof Nowak: Śląsk Cieszyński od Wiosny Ludów do I wojny światowej (1848–1918) . Starostwo Powiatowe w Cieszynie, Cieszyn 2013, ISBN 978-83-935147-3-1 , p. 76 (Polish).

- ^ Dictionary of German loanwords in the Teschen dialect of Polish

- ↑ Zbigniew Greń: Zakres wpływów niemieckich w leksyce gwar Śląska Cieszyńskiego [extent of German influences in the vocabulary of dialects of Cieszyn Silesia]

- ↑ Śląsk Cieszyński od Wiosny Ludów ..., 2013, p 53rd

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, p. 282

- ↑ Hannan, 1996, pp. 159-161

- ↑ Zbigniew Greń: Wpływy Górnośląskie na dialekty cieszyńskie [Upper Silesian influence on the Cieszyn dialects], 2001

- ↑ Hannan, 1996, p. 129.

- ↑ Piotr Rybka: Gwarowa wymowa mieszkańców Górnego Śląska w ujęciu akustycznym . Uniwersytet Śląski w Katowicach . Wydział Filologiczny. Instytut Języka Polskiego, 2017, Śląszczyzna w badaniach lingwistycznych (Polish, online [PDF]).

- ↑ Zbigniew Greń: Identity at the Borders of Closely-Related Ethnic Groups in the Silesia Region , 2017, p. 102.

- ↑ Hannan, 1996 p. 154

- ↑ Hannan, 1996, pp. 85-86.

- ↑ A Czech site about the dialect

- ↑ Jiří Nekvapil, Marián Sloboda, Petr Wagner: Multilingualism in the Czech Republic (PDF), Nakladatelství Lidové Noviny, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Słownik gwarowy ..., 2010, p. 28

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, pp. 60-64

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, p. 64

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, pp. 60-61, 64-65

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, pp. 60-61, 65-68

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, pp. 60-61, 68-70

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, pp. 60-61, 70-73

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, pp. 60-61, 73-74

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, pp. 60-61, 75-76

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, pp. 60–61, 77

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, pp. 60–61, 77

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, pp. 60–61, 76

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, pp. 60–61, 78

- ↑ Z. Greń, 2000, pp. 60–61, 77

- ↑ Piotr Rybka: Gwarowa wymowa mieszkańców Górnego Śląska w ujęciu akustycznym . Uniwersytet Śląski w Katowicach . Wydział Filologiczny. Instytut Języka Polskiego, 2017, Fonetyka gwar śląskich (Polish, online [PDF]).