How does religion come about?

The book How does religion come about? (WeR) is a work by the British philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947), first published in 1926 under the original title Religion in the Making . The essay emerged from a series of lectures Whitehead had given at King's Chapel in Boston . It can be attributed to Whitehead's late philosophy, which found its full formulation in the scriptures Process and Reality and Adventure of Ideas . Thematic is How does religion come about? a brief religious-philosophical examination of the general phenomenon of religion . Whitehead, who, at the age of 65 at Harvard , designed a complete cosmology based on his earlier work on natural philosophy , tries to explain the connection between religious issues and his general process philosophy . This is done more like a woodcut, so that the little book can neither be viewed as an examination of works on the history of religion nor as a systematic elaboration of a certain theological position.

For Whitehead, religious experience was a special kind of experience whose reality cannot be denied (WeR 62). It is a special way of accessing the world, “an unquestionable fact throughout the long span of human history”. (WeR 13) A speculative philosophy that has the task of generating a coherent and adequate view of the world must therefore also be able to explain the phenomenon of religion. Whitehead defined religion as the "art and theory of inner life" that helps to form character . Religion is a necessary part of human thought. “ Science stimulates a cosmology; and everything that aims at a cosmology also brings a religion with it. "(WeR 106) Whitehead viewed the respective form of religion as an evolutionary , historical process in the development of mankind, which on the one hand serves to promote social relationships, on the other hand, it helps to cope with the inner experience that man has in the face of the insight into his imperfections. Modern religions are rationalized and thus possibly compatible with the scientific worldview. Their dogmas lay claim to universal validity for the individual in his existential loneliness. The rationality of the philosophy of religion serves to test and demand the compatibility of the teachings with the experiences. With this understanding Whitehead developed his own panentheistic concept of God , which for him finds expression in the striving of the processes in the world for harmony . God enables an aesthetic order to which a moral order belongs. God is the companion who gives the certainty that the good overcomes the bad again and again.

The work is considered the starting point of process theology . The internationally common seal of the work is RM .

Classification in the overall work

Whitehead wrote the text before his major metaphysical work, Process and Reality, and after Science and Modern World , the first treatise assigned to his late philosophy. In these three works a development of the religious-philosophical conception of Whitehead can be seen in the sense of a deepening and more complete elaboration of his position. First considerations can be found in two chapters (11: God and 12: Religion and Science), which Whitehead had only added retrospectively in science and the modern world . The thoughts suggested here are explained in How does religion come about? elaborated and deepened without breaking the representation. In contrast to science and the modern world, the subject of God and his role in the metaphysical worldview permeates the entire work process and reality . In addition, the final chapter in the final interpretation is dedicated to the question of “God and the world”. Through this exposed treatment “philosophical theology can be thought of as the culmination of metaphysics”.

content

The concept of religion

Religion needs justification . It determines the character of the person and "is the power of faith that purifies the inwardness" (WeR 14), if the person honestly lives his faith. "Religion is the art and the theory of inner human life, insofar as it depends on the person himself and on what is permanent in the nature of things." (WeR 15-16) The description of religion as a social fact is insufficient because the value of religion results from "the inner life, which is the self-realization of existence". (WeR 15) Religion is essentially an inner experience that influences one's attitude to life. "Religion is what the individual makes of his own solitary existence." (WeR 15, 39)

In relation to concrete, historical religious institutions , Whitehead showed a clear distance. “Collective enthusiasm, revival movements, institutions, churches, Bibles, norms of behavior are the outer signs of religion, its ephemeral forms. They can be useful or harmful, they can be authoritatively decreed or just temporary makeshifts. But the goal of religion lies beyond all of that. "(WeR 17)

Religion is the area of experience in which values play a particularly important role. Whitehead cautioned against the idea that religion is good in itself. “It can even be very bad. The fact of evil, interwoven with the texts of the world, shows that in the nature of things a pejorative force remains at work. ”(WeR 17) Religion cannot be viewed in isolation from the question of theodicy . God can also be a God of destruction.

Religion as a historical phenomenon

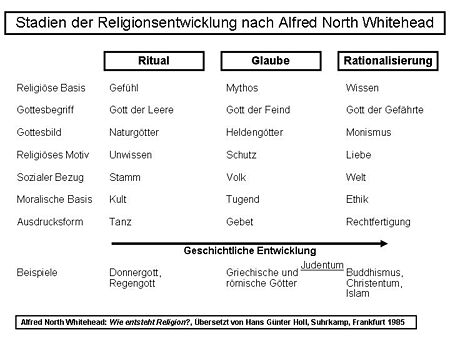

According to the state of social development, Whitehead saw four aspects that determine the character of religion. “These factors are ritual , feeling , belief and ultimately rationalization .” (WeR 16) The origin of religious thought are rituals that can already be found in the animal world. Rituals are “a product of excess energy and idleness” (WeR 18). Regardless of practical, animal needs, rituals are used to renew positive feelings. They serve to maintain cohesion in a community, an early human group, or a tribal society. Religion, like games or drugs, has the function of increasing sensitivity. (WeR 19)

For Whitehead, myths are already a step in the development of society. People try to explain the world by forming myths, but without a systematic order of empirical experience. “The myth explains the purpose of both the ritual and the feeling. It is the product of a lively imagination of primitive people in an unexplored world. ”(WeR 21) The religion at this stage demands a belief that includes a claim to truth , that is, the first beginnings of a rational justification. In faith there is an interest in averting evil and promoting good . Religious belief is therefore suitable for tying larger social units to a set of rules. The Jewish religion represents a transition to the world religions , the characteristic of which is rationalization. It is still tied to a people, but already monistic . However, as in the Roman state religion, the strong bond with one's own people leads to a "pathological exaggeration of national self-confidence." (WeR 35)

Buddhism , in which religious feeling relates to the individual and claims validity for everything that lives and can suffer , claims real general validity, regardless of the social context . Islam and Christianity make a similar claim . In these religions, the individual, as a solitary figure, is detached from his ties to his tribal relationships and confronted with rules of universal validity. The emergence of these religions can also be traced back to great personalities who usually had a formative experience as the starting point for their work.

- “The great religious designs as they permeate the imagination of civilized humanity are scenes of solitary existence. Prometheus chained to the rock , Mohammed brooding in the desert, the meditations of Buddha , the solitary man on the cross . It belongs to the depth of the religious spirit to have felt abandoned, even by God. "(WeR 17-18)

In rational religion, man looks for a belief system that allows him as an individual to find his way around in the modern world. "Rational religion is the religion whose beliefs and rituals are reorganized with the aim of making them a central element of a coherent order of life - an order that both in terms of the clarification of thought and in terms of the orientation of behavior towards a uniform purpose, enforcing ethical consent should be coherent. [...] The tenets of rational religion aim to be the metaphysics that can be derived from the above-average experience of mankind in moments of highest insight. "(WeR 26-27) A" world consciousness "arises in which the individual himself united with the world as a whole through the experience of uniqueness and loneliness. “Rational religion is the more far-reaching conscious reaction of people to the universe in which they find themselves.” (WeR 34) It can only arise when people are able to develop the relevant general ideas and abstract ethical principles.

Rational religions summarize the universal principles that are valid for the individual in dogmas. The two most developed religions in terms of rationality, Christianity and Buddhism, are based on different concepts. Buddhism is a metaphysics that gives birth to a religion. His theorems result from a clear metaphysical idea. Christianity, on the other hand, was from the start a religion, the starting point of which was sayings and actions of particular people. As a result, Christianity had to develop metaphysics to support the religious teaching of the Sermon on the Mount and the parables .

- “Buddhism and Christianity have their respective origins in two inspired moments in history: in the life of Buddha and in the life of Christ. Buddha gave his teaching to illuminate the world; Christ gave his life. It is up to Christians to see the doctrine clearly. In the end, the most valuable part of the Buddha's teaching is perhaps its interpretation of his life. ”(WeR 45)

Religious experience

According to Whitehead, religion is an area of experience that stands independently alongside the area of experience of sensory perception and, like this, can be described by doctrines or "dogmas". “The dogmas of religion are approaches to precisely formulate the truths revealed in the religious experience of mankind. In exactly the same way, the dogmas of physics are attempts to precisely formulate the truths uncovered in the sensory perception of mankind. ”(WeR 47)

The religious experience contains three basic elements that are interrelated (WeR 47-48):

- The self-esteem of an individual

- The value of different individuals to one another

- The value of the objective world for the individual as well as for the community of individuals, who are all interconnected and thus make up the universe.

Religious experience is always associated with values. It asks about the valuable meaning of what has been experienced, taking into account feelings and intentions as well as the physical conditions. Valuing means harmonizing individual demands with the realities of the objective universe. "Religion is loyalty to the world ". (WeR 48) This agreement means harmony , which is in the nature of things and can be more or less fully achieved. If the match is incomplete, there is evil in the world. (WeR 49) Whitehead equated evil with a lack of proper harmony.

From the question of the character of the right harmony arises the question of the personal God who determines what is right. Is there God's will that can be known? Can one grasp God directly and intuitively ? In the Asian religions Confucianism , Buddhism and Hinduism , the personal God does not exist in this sense. “There can be personal embodiments, but the substratum is impersonal.” (WeR 50) Christianity is based on a personal God, but forbids forming an image of him. God as truth is an idea that is a conclusion from religious experience. The teaching of access to a personal God is rejected in the classic Christian denominations. Here Christianity ties in with ancient Greek thought. “In a way, in ancient Greece, all attempts to formulate the teachings of a rational religion were based on the Pythagorean notion of direct intuition of a justice in the nature of things which worked as a condition, criticism, and ideal. The divine personality lay in the nature of a conclusion from the directly conceived law of nature, provided that the conclusion was actually drawn. ”(WeR 50-51)

A religion based solely on feeling can claim anything, but contradicts reason . Intuition is an individual, psychological matter that has no claim to general validity. They can give a nudge to religious thinking, but must be rationalized in order to have a supra-personal meaning. "Reason mocks the majority." (WeR 53) In this context, however, there is the feeling of elementary religious evidence of the correctness of the nature of things, "beyond which one can no longer refer to anything." (WeR 53)

The simultaneously immanent and transcendent God

In the search for an appropriate concept of God, one finds three concepts in history (WeR 54):

- The Asian concept of an impersonal order of a self-organizing world

- The Semitic concept of a personal, almighty and transcendent Creator God who shapes the world according to his will and intervenes in it

- The pantheistic concept that the real world is a partial description of the transcendent God.

The Asian and pantheistic concepts are compatible. They differ in perspective. “According to that, when we speak of God, we say something about the world; and after this, when we speak of the world, we say something about God. ”(WeR 54-55) The Asiatic and Semitic concepts are incompatible as long as one does not transfer the Semitic to the pantheistic concept. ( Spinozism ) In the Semitic concept, God defies any rationalization. Man is at the mercy of God's will and therefore has no explanation for evil. In addition, the god of the Semitic concept eludes any attempt to prove his existence. Even the ontological proof of God , according to which the mere concept of God proves his existence, does not stand up to logical criticism. “By examining the world, we can find all the factors that are presupposed by the overall metaphysical situation; but we do not develop anything that does not belong to this totality of real facts and yet explains them. ”(WeR 56) The realm of the transcendent remains closed to man.

Compared to the traditional Semitic concept, the New Testament has brought about important changes. On the one hand, there is the idea of the immanence of God (“The kingdom of God is among you”). On the other hand, it is the primacy of love that is expressed in the idea of God the Father. “At that time [in the first epoch of Christianity] Christian theology was Platonic ; she followed John rather than Paul . ”(WeR 58) In the course of its history, however, the Church has abandoned this path and in the development of her dogmas, e. B. the commitment to the Trinity of God, again approximated the Semitic concept.

Whitehead rejected both the "extreme doctrine of transcendence" ( dualism ) and the "extreme doctrine of immanence" ( pantheism ). Whitehead's characterization of God is that of "immanent transcendence". God is part of the cosmos and in his properties exceeds every part of the cosmos. By creating order in the world, God creates contrasts, i.e. differences that make it possible to distinguish between finite events. As the reason for the differences, he is contained in his creatures, but at the same time cannot be distinguished as a difference. It is involved in all processes of becoming and passing away, but does not become and does not perish itself. Usually process theology is assigned to panentheism (see the article God ).

Religion and metaphysics

In the third chapter of How Does Religion Come About? Whitehead sketched his metaphysical cosmology, which he presented in more detail and further developed in process and reality . The idea of the world as a process is fundamental. Whitehead called the process elements, which in turn are processes, “ actual entities ”. In How Religion arises? He also used the term "epochal event" ( epochal event ). Epochal events are inevitable primordial elements of the universe, which through a multitude of connections form the network-like structures of the universe, and whose processuality is expressed in an incessant becoming and passing away.

- “The universe thus revealed is interdependent through and through . The body desecrates the mind and the mind desecrates the body. The biological goals are transformed into ideals for norms, and the formation of norms influences the biological facts. The individual shapes society, this the individual. Individual evils damage the world, special forms of the good show the way out. ”(WeR 67-68)

In this statement two particular elements of Whitehead's metaphysics are addressed. On the one hand, the original events, the real individual beings, always include both a spiritual and a physical aspect. Inorganic structures such as stones also have a kind of sensation in that they “react” to their environment and changing conditions in the environment (e.g. heat, pressure) and “behave” to this environment. On the other hand, every primal event has an inner subjective goal towards which it develops in its becoming. A stone “strives” to assume a stable position and to follow gravity. The flow of events in nature is not only causally conditioned, but also follows purposes that are ultimately laid out in these events . Therefore, environmental influences are a date that evaluates the original event in terms of its inherent subjective goal. The interplay between the events is decisive.

- “The real world, the world of experience, thought and physical activity, is a community of many different individuals; and these individuals add to or harm the common value of the entire community. At the same time, these real individual beings are themselves their own worth, they are individual and can be separated from one another. They contribute to the common supply and yet suffer for themselves. The world is a stage for solitary existence in a community. "

- “The individuality of individuals is just as important as their community. The theme of religion is individuality in the community. "(WeR 68)

The mechanisms of action that keep the interplay between the original events and thus the process of ongoing growth and decay in the real world of time in motion, Whitehead called "form elements". These are (WeR 70):

- The creativity through which a constant transition into the new takes place

- Ideal entities or forms that have no reality of their own, but exemplify themselves in relation to their relevance in the events

- The real but not temporal individual being through whom the indeterminacy of mere creativity is transformed into a certain freedom , God.

The becoming of the original events is incomplete. The universe is an open system . Real or epochal events have an expansion in space and time. When they are completed as an event, they go into the constantly emerging events as a date. Due to the infinite variety of forms, comparable to the ideas of Plato or the universals , there is an infinite space of possibilities of how the new emerges from the past events. Creativity lies in the way in which the various events are synthesized in a new epochal event, in a new "creature". This is an interplay.

- “In concretion, the creatures are qualified by the ideal forms, and conversely, the ideal forms are qualified by the creatures. Hence, the epochal event that emerges in this way has in its nature the other creatures under the aspect of these forms, and accordingly it includes the forms under the aspect of these creatures. Accordingly, it is a definite, limited creature that arises as a result of the limitations which the elements so mutually impose on one another. ”(WeR 72)

The way in which a nascent epochal event is concretized depends on the purposes inherent in it, its subjective goal. “Value is part of reality itself. To be a true individual is to have self-interest. This self-interest is a sense of self-worth; it's an emotional mood. The value of other things outside of oneself is the derived value of being elements that contribute something to this elementary self-interest. ”(WeR 76-77) Every epochal event has both an inwardly directed, subjective intrinsic value as well as an objective for the outer world relevant value. “The purpose of God is the achievement of value in the temporal world.” (WeR 76) God is the timeless principle of harmony in the world. The goal of a harmonious order arises through God. Because the epochal events in the creative process are free within the given possibilities, it is possible that they lack harmony. This is how evil arises in the world. It is a violation of the aesthetically harmonious order.

- “Order is therefore always an aesthetic order, and the moral order consists only of certain aspects of the aesthetic order. The real world is the result of the aesthetic order, and the aesthetic order is derived from the immanence of God. "(WeR 80)

The cause of evil is creativity, because without creativity there would be no becoming that can violate the harmonious order in the world. Without creativity, no creative process would be possible at all. “A complete determinism would therefore mean the complete conformity of the temporal world with itself.” (WeR 73) There would only be standstill. However, the facts speak against this. With complete determinism, evil would be part of God's will. Theodicy is a problem that all religions that assume an almighty God have. There is a striving in the world to eliminate evil and return to harmony. Evil is therefore unstable . Its destructive effects also contain the goal of undoing it again. “The contrast that exists in the world between evil and good is that between the revolt of evil and the“ peace that is higher than all reason ”. What is good in itself has a power of self-preservation . ”(WeR 75) God as such does not contain any evil, but through him the world strives for harmony. "So God is the measure of the aesthetic consistency of the world." (WeR 76)

Just as process philosophy escapes the theodicy problem, the mind- body problem is not relevant to it either. Because all epochal events have both a physical aspect and a subjective mental feeling, the dualism of physical and mental substances in process thinking , as Descartes had conceived it, is a misjudgment about the tangible nature. Substances in the sense of matter are not the original building blocks of nature. Rather, these are the processes of becoming and passing away of epochal events. Substances and things are already conceptual abstractions from them that result from the fact that a sequence of individual events exhibits a certain stability. A stone that a person perceives to be stable and unmoving shows incessantly considerable changes in its molecular structure. The film is a metaphor for this fact. In an analog film or on television, a sequence of individual images creates the impression of movement. In digital systems only individual pixels are exchanged. In fact, after every change there is a new constellation that is captured as a new “drop of perception” while the old one has passed. In process philosophy there is no opposition between body and mind, because bodies are a series of related events that each also contain the spiritual aspect. Matter and spirit are generated in the imagination by the order immanent in the world, through which the creative energy incessantly “focuses the universe into a unity”. (WeR 85) In the process, a "real event that has become" enters into the birth of another case of value experience. (WeR 85) “The whole world works together to bring about a new creation. It offers the creative process its opportunities and its limitations. "(WeR 86)

- “The order of the world is no accident . Nothing real could be real without some degree of order. Religious insight is grasping this truth: that the order of the world, the depth of the reality of the world, the value of the world in its entirety and in its parts, the beauty of the world, the dignity of life, the peace of life and the Mastery of the evil all related - not by chance, but because of this truth: that the universe exhibits a creativity with infinite freedom and a sphere of forms with unlimited possibilities; but that this creativity and these forms are also not jointly able to achieve reality without perfect ideal harmony, and this harmony is God. "(WeR 90)

Religious truth

Rationalization also means that religious truths cannot contradict scientific knowledge. If it comes to an alienation from religion and science, it is mainly because a theology dogmatically remains at a standstill and closes itself off to the new. From Whitehead's point of view, this is a mistake by the religious representatives. "One can protect neither theology from science, nor science from theology." (WeR 61)

Religious truths must be coherent in order to be suitable for the interpretation of life. "The peculiarity of religious truths lies in the fact that they expressly have to do with values." (WeR 93) Through these values one's own existence takes on meaning . This meaning, which also includes an emotional apprehension, is often not sufficiently expressible through language because appropriate terms have not yet developed. Leibniz and Newton , for example, developed the principles of differential calculus . It took more than 200 years for the appropriate mathematical terms to emerge. (WeR 95) “We know more about the character of those who are dear to us than we can precisely express in words.” (WeR 95–96) This insight is important when formulating religious dogmas. They must try to formulate the facts and mechanisms described appropriately. Above all, one has to continually develop such doctrines based on new insights. Rigid dogmas mean standing still. “One cannot claim absolute finality for a dogma without at the same time insisting on the corresponding finality of the sphere of thought in which it arose. […] One can not limit inspiration to a narrow circle of creeds. ”(WeR 98) Progress with regard to truth in religion only arises from an appropriate design of terms. Progress also requires the freedom for special personalities who have the ability to think in particular. “Standard size can do almost anything, just not promote the growth of a genius .” (WeR 101) Religions must be open to new ideas and be aware of their development in their traditions . “Religions commit suicide when they find inspiration in their dogmas. The inspiration of religion lies in its history. ”(WeR 107) In this regard, Whitehead saw a deficit in the major religions and called for a new understanding of God.

- “God is that function in the world by virtue of which our intentions are directed towards goals which in our own consciousness are unprecedented for our own interests. He is that element in life by virtue of which judgments extend beyond the facts of existence to values of existence. It is the element by which our intentions expand beyond values for ourselves to values for others. He is the element by means of which the achievement of such a value for others is transformed into a value for ourselves. "

- He is the binding element in the world. The consciousness that is individual in us is universal in him; the love that is partial and partial in us is all-embracing in him. Without him there could be no world, because an adaptation of individuality would be impossible. Its purpose in the world is the quality of achievement. Its purpose is always embodied in the ideals that are relevant to the real state of the world. [...]

- “The current type of order in the world has emerged from an unimaginable past, and it will find its grave in an unimaginable future. What remains is the inexhaustible sphere of abstract forms and creativity with its shifting character, which is determined again and again by its own creatures, and God, on whose wisdom all forms of order depend. ”(WeR 117-119)

Further developments in process and reality

In process and reality , too , Whitehead placed religion in a historical context and emphasized the peculiarity of love as a driving, not static force:

- “In the great development phase of theistic philosophy, which ended with the rise of Islam, three schools of thought emerged simultaneously with civilization after a further development Personification of moral energy and to represent God according to a basic philosophical principle. […] The history of theistic philosophy shows different phases of combining these three different ways of dealing with the problem. There is, however, another type of stimulus in the Galilean origin of Christianity that does not really fit any of the three main strands of thought. It puts the emphasis neither on the ruling emperor, nor on the merciless moralist or the immobile mover. She holds fast to the delicate elements of the world, which work slowly and quietly through love; and it finds its purpose in the present immediacy of the kingdom which is out of this world. Love neither rules nor is it motionless; nor is it negligent towards morality. "(PR 612–613)

However, process and reality contain at least two aspects that are discussed in How does religion come about? not yet stand out clearly. On the one hand there is the special emphasis on creativity as the independent driving force of the world, which is also subject to God. On the other hand, Whitehead only worked out the bipolarity of God in his later work, who on the one hand, as the source of all events, invariably determines the purpose and goal of the world, but on the other hand, as contained in the world, depends on its becoming. In this sense, God not only has an "original nature", but also a "subsequent nature".

reception

Whitehead's understanding of religion has found more than his general metaphysics in process philosophy , especially in theological circles. The concept of process theology includes a number of conceptions that are directly linked to him, but also to his most important student Charles Hartshorne , who interpreted Whitehead's metaphysics as a philosophical theology. Other important representatives include Ian G. Barbour , John B. Cobb , David Ray Griffin , Roland Faber , Lewis S. Ford , Joseph A. Bracken SJ (* 1930), C. Robert Mesle (* 1950), Michael Welker and Godehard Bruntrup .

Natural scientists who have also dealt with questions of the philosophy of religion and who represent a process-oriented panentheism are Charles Birch , Arthur Peacocke and John Polkinghorne , who is also directly connected to Whitehead.

Well-known Jewish process theologians are Milton Steinberg (1903–1950) and Max Kadushin (1895–1980).

Independent parallels to Whitehead's religious philosophy can be found in Martin Buber , Pierre Teilhard de Chardin , Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan or Sri Aurobindo .

Individual evidence

- ↑ King's Chapel in Boston - not to be confused with King 'College Chapel at King's College of the University of Cambridge

- ↑ in the German edition How does religion come about? 119 pages without the index

- ↑ Whitehead uses the term "dogmas" neutrally as "doctrine"

- ↑ Walter Jung: On the development of Whitehead's concept of God. In: Journal for Philosophical Research. 19, (4/1965), p. 604.

- ↑ Roland Faber: God's Sea. ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. pdf page 13 (accessed October 5, 2011)

- ↑ John B. Cobb, David R. Griffin: Process Theology. An introductory presentation. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1979, pp. 12-13

- ↑ "I agree in principle with the theology of nature and combine it with a careful use of process philosophy" In: Ian G. Barbour: Science and Belief. Historical and contemporary aspects. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, p. 149.

- ↑ Andreas Losch: Beyond the Conflicts: A Constructive-Critical Discussion of Theology and Science. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2011, p. 240.

- ↑ Donald Viney: Process Theism. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

expenditure

- Religion in the Making . [1926] with an introduction by Judith A. Jones. Fordham University Press, New York 1996 (online)

- How does religion come about? Translated by Hans Günter Holl. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1985.

literature

- John B. Cobb, David R. Griffin: Process Theology. An introductory presentation. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1979.

- Ingolf U. Dalferth : Theoretical theology of the process philosophy of Whitehead. An attempt at reconstruction. In: ders .: God. Philosophical-theological attempts at thought. Mohr-Siebeck, Tübingen 1992, pp. 153-191.

- Roland Faber: God as the poet of the world. Issues and perspectives of process theology . Knowledge Buchges., Darmstadt 2003.

- Reto Luzius Fetz : Whitehead's concept of a religion in the making and the theory of modernity. In: Helmut Holzhey , Alois Rust, Reiner Wiehl (eds.): Nature, Subjectivity, God: To the process philosophy of Alfred N. Whitehead. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1990, pp. 278-300.

- Lewis S. Ford: The Emergence of Whitehead's Metaphysics . State University of New York Press, Albany 1984.

- Walter Jung: On the development of Whitehead's concept of God. In: Journal for Philosophical Research. 19, (4/1965), pp. 601-636.

- Michael Hampe : Alfred North Whitehead . CH Beck, Munich 1998.

- Michael Hauskeller: Alfred North Whitehead as an introduction . Junius, Hamburg 1994.

- Helmut Maaßen: God's relationship to good and evil in Whitehead's rational ethics of values. In: Helmut Holzhey, Alois Rust, Reiner Wiehl (eds.): Nature, Subjectivity, God: To the process philosophy of Alfred N. Whitehead. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1990, pp. 262-277.

- C. Robert Mesle: Process-Relational Philosophy: An Introduction to Alfred North Whitehead . Templeton Foundation Press, 2008.

- Tobias Müller: God - World - Creativity: An Analysis of AN Whitehead's Philosophy . Schöningh, Paderborn 2008.

- Wolfhart Pannenberg : Atom, Duration, Shape. Difficulties with the process philosophy. In: Friedrich Rapp , Reiner Wiehl (Ed.): Whiteheads Metaphysics of Creativity. Internationales Whiteshead Symposium Bad Homburg 1981. Alber, Freiburg 1986, pp. 185-196. ( English version )

- Michael Welker : Whitehead's deification of the world. In: Hans H. Holz, Ernest Wolf-Gazo (ed.): Whitehead and the concept of process: Contributions to the philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead at the 1st International Whitehead Symposium 1981. Alber, Munich 1984, pp. 249-272.

- Michael Welker: Universality of God and Relativity of the World: Theological Cosmology in Dialogue with American Process Thinking according to Whitehead. 2nd Edition. Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2008.

Web links

- Roland Faber: Process theology (PDF; 3.1 MB), In: Theologies of the present. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2005, pp. 179–197.

- Roland Faber: On the Unique Origin of Revelation, Religious Intuition, and Theology (PDF; 561 kB)

- Lewis S. Ford: The Growth of Whitehead's Theism (PDF; 312 kB)

- Javier Monserrat: Alfred N. Whitehead on Process Philosophy and Theology (PDF; 255 kB). Cosmos and Kenosis of Divinity, PENSAMIENTO, vol. 64 (2008), núm. 242, pp. 815-845,

- Forrest Wood, Jr .: Whiteheadian Thought as a Basis for a Philosophy of Religion

- Alfred North Whitehead (texts and essays on the homepage of Anthony Flood - English)