Forced treatment

A compulsory treatment or medical coercive measure is by a physician without or against the natural will carried out by the person concerned examination, medical treatment or medical intervention § 1906a of the Civil Code (BGB).

history

Legendary in the world of psychiatry was the so-called “liberation of the sick from their chains” by the French psychiatrist Philippe Pinel in the Bicêtre Hospital in Paris (1793), by Abraham Joly in Geneva (1787), by the Quaker William Tuke on specifically by the Quaker community built a hospital retreat in York (1796) or by Johann Gottfried Langermann in Bayreuth (1805). It is considered to be the hour of birth of progressive modern psychiatry. From 1839 the British doctor John Connolly advocated the maxim of renouncing any mechanical coercion ( no restraint ).

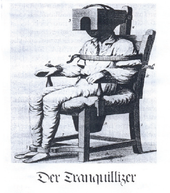

The somatotherapeutic means of immobilization that became popular in the 19th century included the forced chair , the straitjacket (forced camisole ), the forced bed, the standing chest (forced cupboard, English coffin), the forced belt (Toll strap) and handcuffs and ankle cuffs.

The opposite therapeutic principle, calming or exhaustion through movement, included the swivel chair (Cox's swing, Darwin's chair), the swivel bed (gyrator), and the “ hollow wheel ” (according to Hayner ). In the swivel chair and in the swivel bed, the blood pressure in the heads of the patients increased due to the rotation, until vomiting, fainting or bleeding occurred. Patients should let off steam in the hollow wheel. The Autenrieth palisade rooms, with isolation cells secured by wooden palisades, also served to act out the unrest.

Other procedures included falling baths with cold water, hot or cold forced baths , enemas , electroconvulsive therapy , insulin shock therapy, and shock therapy with pentetrazole , as well as red- hot iron.

The psychosurgical methods included or include the lobotomy , the thalamotomy and the cingulotomy .

In the 20th century, drugs gained importance in the field of “chemical restraint”.

The avoidance of coercion in the treatment of the mentally ill has been and is decisive for the progress of psychiatric science. In 1969, Klaus Dörner spoke of a dialectic of coercion in psychiatry. Asmus Finzen spoke of the Pinel pendulum in 1998 . This refers to the vicissitudes of history in which a reform of psychiatric institutions, guided by new therapeutic ideas, reveals new forms of coercion over time.

According to this idea, every therapeutic idea has so far proven to be relative and could not prove to be helpful in all cases of mental illness. Rather, unpleasant effects have repeatedly been shown which make the one-sided insistence on very specific therapeutic methods appear compulsive. The dialectic of coercive treatment received further impulses for liberation from coercion through the consultation hour psychiatry that had been emerging in Germany since the middle of the 19th century .

Forced treatment in Germany

A death in 1811, when a patient of the psychiatrist Ernst Horn was put in a sack in the Charité asylum and suffocated, led to the first medical liability litigation in Germany.

In Germany, the ideas of the physician Johann Christian Reil (1759–1813) were decisive. As a reformer of psychiatry and a proponent of the institutional system, he wanted to adapt the Western concept of moral treatment to the " psychological treatment method " he called for in Germany . This should be introduced as a third method in addition to the surgical and medical measures that can also be used for other physical illnesses.

With the adoption of the UN Disability Rights Convention in German law in 2009, patient autonomy came to the fore. In this context, Germany committed itself to protecting and strengthening the principles of self-determination , freedom from discrimination and equal participation in society for people with (mental) disabilities and impairments .

The living will was by the Third Amendment of the guardianship law under § 1901a included in the law. It came into force on September 1, 2009. It should create more legal certainty with regard to the rejection of life-prolonging or life-sustaining measures in the run-up to death (waiver of treatment, passive euthanasia ).

Legal care consent to a compulsory medical measure

Based on the rulings of the Federal Constitutional Court and the Federal Court of Justice , the legislature created a legal basis for compulsory medical measures in the care law of February 18, 2013 by adding to Section 1906 of the German Civil Code (BGB) with the law regulating the consent under care law . The law with which compulsory treatment was fundamentally reorganized came into force on February 26, 2013.

According to this, compulsory medical treatment according to Section 1906, Paragraph 3 of the German Civil Code (BGB) was only permitted in the context of inpatient accommodation according to Section 1906, Paragraph 1 of the German Civil Code. Another prerequisite was that the patient “could not recognize the necessity of the respective medical measure or could not act according to this insight” (Section 1906 (3) No. 1 BGB) and was therefore unable to give consent. In addition, the compulsory medical measure had to be necessary for the well-being of the person being cared for, in order to "avert the threat of considerable damage to health" (Section 1906, Paragraph 3, No. 3 BGB). Another prerequisite was that this damage could not be averted by “another measure that could be reasonably expected of the person being cared for” (Section 1906, Paragraph 3, No. 4, BGB). Ultimately, “the benefit to be expected had to clearly outweigh the impairments to be expected” (Section 1906, Paragraph 3, No. 5 BGB), and before the coercive measure was initiated, an attempt had to be made “to inform the patient of the necessity of the medical measure convince". Only the natural will of the person concerned was decisive for the existence of compulsory medical treatment in accordance with Section 1906 (3) BGB. It had to be clear from the behavior of the person concerned that he did not agree to the medical treatment. If there were no signs of this, there was no compulsory treatment - even if it was a patient who was incapable of giving consent. If the patient who was incapable of giving consent, who did not recognize the need for treatment and who did not act in accordance with this opinion, nevertheless consented to the treatment, a decision by the carer was sufficient for the implementation of the measure. In addition, the approval of the Supervision Court according to Section 1904 of the German Civil Code - not, however, according to the new Section 1906 of the German Civil Code - was only necessary for certain treatments (e.g. major operations). The following also applied: a proxy was only authorized to consent to compulsory medical measures if the proxy expressly contained this authorization.

According to the law of 2013, the initiation of a coercive measure always required judicial approval (Section 1906, Paragraph 3a of the German Civil Code). Any consent given by the supervisor alone was never sufficient, not even in urgent cases. Furthermore, the law on compulsory treatment did not include the supervisor's authority to issue emergency orders. Even in the case of imminent danger, compulsory treatment could not be started without a court decision. The law also did not contain any (supervision) judicial authority to issue an emergency order in the event that no supervisor has yet been appointed who could submit an application for compulsory treatment. The law also tightened the procedural and content-related hurdles to judicial approval. The judicial approvals were limited in time (in urgent court proceedings from six to a maximum of two weeks ( Section 333 (2) FamFG new version) with the possibility of changing the court decision to up to six weeks, in main proceedings to a maximum of 6 weeks, whereby the deadline but can be extended as often as necessary), detailed questions about medical treatment had to be determined ( Section 323 (2) FamFG new version) and an assessment was only possible by an uninvolved external expert who had not previously treated or assessed the person concerned and was also not working in the facility in which the person concerned was housed.

On July 26, 2016, the Federal Constitutional Court decided to close the gap in protection for persons under care who are unable or unwilling to evade the measure and who therefore cannot be ordered to be deprived of their liberty (Az. 1 BvL 8/15) . This means that compulsory medical treatment is also permitted for patients without a placement decision. However, they no longer have to be able to move around on their own or do not want to escape treatment spatially, or are voluntarily in a psychiatric hospital. The other prerequisites of Section 1906 (3) BGB must also be met and, as in the case of accommodated patients, approval from the supervision court is required. The German legislator was obliged to immediately come up with a regulation for the group of cases described above.

A ministerial draft from the Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection had been available for a corresponding revision of Section 1906 BGB since 2016 . With the law amending the material admissibility requirements for compulsory medical measures and strengthening the self-determination of those in care , consent to compulsory medical measures is to be decoupled from custodial placement while maintaining the other requirements. For example, judicial approval should remain tied to inpatient placement in suitable facilities, and compulsory outpatient treatment should continue to be prohibited. An express priority of living wills is also intended to strengthen the self-determination of those in care. With regard to the effectiveness of the protective mechanisms, among other things, the law is to be evaluated three years after it came into force. In March 2017, the Federal Government defended the German practice of coercion in psychiatric facilities when it was feared that there would be considerable danger to oneself or others.

The law to change the material admissibility requirements for compulsory medical measures and to strengthen the right of self-determination of those receiving care was passed in an amended version on June 22, 2017 by the Bundestag and on July 7, 2017 by the Bundesrat. It came into force on July 22, 2017. The changes include:

- Strengthening the self-determination of those affected by the consent of the caregiver to a medical measure in place of the patient being treated only if the medical measure corresponds to the patient's wishes to be observed. For this decision by the supervisor, the living will (Section 1906a Paragraph 1 No. 3 BGB new version), treatment requests and the presumed will of the person being looked after are decisive in this order.

- Avoidance of compulsory medical treatment through a two-stage approval process, according to which, in a first step, a decision should generally only be made about the forced transfer to a hospital. Only in a second step should a decision be made as to whether the approval of the consent for a compulsory medical measure can be given. Compulsory outpatient measures are still excluded (Section 1906a Paragraph 1 No. 7 BGB new version), because compulsory medical measures are tied to the requirement of an inpatient stay in a hospital in which the necessary medical care for the person being cared for, including the necessary follow-up treatment, is ensured.

- Specification of the attempted persuasion in the case of compulsory treatment in the sense of the case law of the Federal Constitutional Court by the wording "an attempt was made beforehand seriously, with the necessary expenditure of time and without exerting inadmissible pressure" (Section 1906a Paragraph 1 No. 4 BGB new version). This is to help the persuasion talk to be more effective. It should not be sufficient to say quickly: "That would be important" and to regard the conversation as over.

- Improvement of the protection of fundamental rights for those affected by the introduction of a right to apply for the establishment of a legal infringement (so-called continuation complaint) for legal counsel and guard advisor of the person concerned for the purpose of judicial determination that a completed measure within a supervision procedure was unlawful ( Section 62 (3) and Section 317 (1) FamFG nF ). This concerns, for example, cases in which those affected are immobilized or immobilized in nursing homes without the necessary requirements. A corresponding determination was previously only possible for an ongoing measure.

The possibility of forcibly treating people who are not housed in a closed psychiatry is viewed critically by critics of the law such as the Federal Association of Psychiatry Experienced People, because in their eyes the decoupling of medical coercive measures from custodial accommodation means an expansion of the possibility of freedom rights to restrict. The psychiatrist Robert von Cube, however, points out that compulsory treatment presupposes, among other things, that due to a mental illness, a mentally ill person is at risk of "killing himself or causing significant health damage" or only such damage can be averted by means of medical measures which the person concerned “cannot recognize due to a mental illness [...] or cannot act on this insight”. In his opinion, the criterion “due to a mental illness” is decisive, “because this means that no one may be treated just because he is also mentally ill. So if someone refuses operations anyway, and has already seen it that way before or regardless of his mental illness, he must not be treated against his will. Because people also have an opinion that may not be influenced by the disease at all. Conversely, if a person with a psychosis thinks that the doctor is an alien who wants to install a chip for him during the operation (but would actually like to be treated outside of the psychosis), compulsory treatment is possible. But only if it has been proven that all other possibilities have been exhausted, that the patient has tried to explain the consequences and if the treatment has any chance of success. "

On January 14, 2015, the Federal Court of Justice ruled on the case of a woman from Lübeck suffering from paranoid schizophrenia who refused to take medication, while a psychiatric expert considered treatment necessary to avoid permanent placement in a closed facility. The Federal Court of Justice ruled that the court approval for compulsory treatment had to contain a note that the treatment could only be "carried out and documented under the responsibility of a doctor" (Az. XII ZB 470/14). The core content of the decision of the BGH is: If, when approving or ordering the consent of a compulsory medical measure, the resolution formula does not contain any information on the implementation and documentation of this measure under the responsibility of a doctor, then the order is altogether illegal and the person concerned is placed in violated his rights. For example, non-medical practitioners are generally prohibited from forced treatment.

Coercive measures according to the mental health laws or state accommodation laws of the federal states

The Saxon law on assistance and accommodation in the event of mental illness (SächsPsychKG) did not stand up to a review by the Federal Constitutional Court after its decision of February 20, 2013 (Az. 2 BvR 228/12).

A patient detained in 2007 under the Baden-Württemberg Accommodation Act fought for himself in 2015 at the Higher Regional Court of Karlsruhe (OLG) 25,000 euros in compensation for pain and suffering against the hospital for unlawful forced placement and compulsory treatment (Higher Regional Court of Karlsruhe, decision of November 12, 2015, Az. 9 U 78/11) . In the present case, the doctors disregarded fundamental professional standards when issuing the medical certificates required for the placement. “There was no basis for a risk prognosis in the sense of a risk to oneself and others. Under these circumstances, it does not matter whether the plaintiff had a mental illness at the time of placement, since a mental illness on its own - without endangering itself or others - cannot justify compulsory placement in a psychiatric clinic. "In the official guiding principles for the resolution of the OLG Karlsruhe were implemented:

- The doctors of a center for psychiatry organized under public law have the official duty to avoid errors in the diagnosis and errors in the risk prognosis when issuing medical certificates that are intended to justify placement.

- The affirmation of endangerment to others or of endangerment to oneself in a medical certificate requires that concrete connecting facts justify the risk prognosis of the doctor.

- The fact that the Guardianship Court should not have ordered the person concerned to be placed on the basis of the inadequate medical certificates does not prevent the Center for Psychiatry from being liable for the mistakes made by the doctors responsible.

- In the event of unlawful placement in a psychiatric hospital for two months that is associated with compulsory medication, compensation for pain and suffering of € 25,000 may be considered.

In 2017 the Federal Constitutional Court ruled in favor of a patient at the MediClin Müritz Clinic (decision of July 19, 2017, Az. 2 BvR 2003/14). In 2014 she was given depot injections with Zypadhera by nurses, doctors and nurses in accordance with the law on help and protective measures for people with mental illnesses (Mental Health Act - PsychKG MV) of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania with increasing doses and the use of force . The Federal Constitutional Court declared that the relevant provision in the specific case § 23 paragraph 2 sentence 2 alternative 1 PsychKG MV old version with Article 2 paragraph 2 sentence 1 in conjunction with Article 19 paragraph 4 sentence 1 of the Basic Law was incompatible and void. The Constitutional Court further stated that the complainant's fundamental right under Article 2 Paragraph 2 Clause 1 of the Basic Law had been violated and in the present case criticized the lack of "prior efforts to obtain consent based on trust and voluntary in the legal sense" with regard to the coercive measure. There are similar regulations in three other federal states, as the Senate criticized. These are the federal states of Bavaria, Lower Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt.

Forced treatment in Austria

The incapacitation order from 1916 regulated compulsory admission and residence until the end of the 1980s.

The diary-like report "Electric shocks and body lichen" by psychology student Hans Weiss from 1977 promotes the discussion about the need for reform.

Since January 1, 1990, the so-called “placement without request”, ie forced admission and detention of patients against or without their will, has been regulated in the Accommodation Act (UbG). Every year around 20,000 people in Austria are forcibly committed.

The use of net beds after criticism from the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and the Ombudsman's Office banned since July 1, 2017th

Forced treatment in Switzerland

In 1999, the Federal Supreme Court found the legal provisions on welfare deprivation of liberty (FFE) as insufficient legal basis for compulsory treatment. Treatment without consent and medical measures in emergencies have been re-regulated in Articles 434 and 435 of the Civil Code for the case of welfare accommodation (FU) .

On May 18, 2017, the Federal Supreme Court closed the complaint of a woman who had been admitted to a clinic for an indefinite period of time because of endangering herself and others against the background of known paranoid schizophrenia and was housed there in an open isolation room. It should be treated with 400 mg of solian and a mixture of valerian root and butterbur. She said that she would be isolated under Art. 438 in conjunction with Art. 383 ZGB if she did not take the medication. The judges upheld the complaint and referred the case to the lower court for a new decision.

Legal basis

International

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) has legal status in states that have ratified the Convention, whereby Article 12 basically guarantees the right to equal treatment with the restriction of paragraph 4. Article 17 reads: "Everyone with disabilities has the right to respect for his physical and mental integrity on an equal footing with others. " All medical treatment is an interference with the right to physical integrity, which requires approval . Treatment of a patient incapable of making a decision in the sense of his or her individual presumed will or an objective presumed will, if the individual will of the patient cannot be determined, is only possible for non-disabled people in Germany in emergencies according to Section 630d (1) sentence 4 BGB. Forced treatment according to § 1906a BGB presupposes a mental illness or a physical, mental or emotional disability according to § 1896 Abs. 1 Satz 1 BGB, i.e. a disability in the sense of the BRK.

According to the report of the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Juan E. Méndez, any coercive treatment that does not serve to avert an acute life-threatening condition is prohibited, regardless of whether the person concerned is able to consent is or not. The report states that compulsory medical treatment that causes irreversible harm can be classified as gross abuse or torture if it is not associated with a therapeutic purpose or if the treatment is given against the individual's free will .

Article 46 of the 2018 Annual Report of the UN Human Rights Council requires states to prohibit compulsory treatment against free will as cruel, degrading inhuman treatment or torture. Laws that allow a representative decision are to be repealed. Instead, voluntary measures that support the decision of the person concerned should be promoted.

In contrast to the Disability Rights Convention (CRPD), the recommendations of the UN Human Rights Council have no legal force.

Legal basis in Germany

According to the prevailing opinion in criminal law, every medical treatment is a factual bodily harm that is only justified if the patient gives legally effective consent or if a legal basis expressly legitimizes compulsory treatment. Conversely, failing to provide urgently required compulsory treatment can also be a criminal offense if the patient refuses treatment due to mental illness or disabilities.

Medical treatment against the natural will of an affected person encroaches on their basic right under Article 2, Paragraph 2, Clause 1 of the Basic Law, which protects the physical integrity of the fundamental rights holder and thus the right to self-determination in this regard.

The compulsory treatment for mental illness takes place to protect the community or to protect the person concerned from serious harm, if the legal requirements for this are met. Compulsory treatment can only be ordered by the judge after hearing the patient.

Federal and state laws stipulate the conditions under which compulsory treatment by the doctor can take place.

Compulsory measure in care law

A compulsory measure according to § 1906a BGB is only permissible under the following conditions:

- the compulsory medical measure is necessary for the well-being of the person being cared for in order to avert the threat of considerable damage to health

- Due to illness, the patient does not grasp the situation or cannot act accordingly,

- if the compulsory medical measure corresponds to the will of the person being cared for according to § 1901a BGB,

- if a serious attempt has been made to convince the patient of the necessity,

- damage to health cannot be averted by any other less stressful measure,

- the expected benefit clearly outweighs the expected impairments and

- the compulsory medical measure is carried out as part of an inpatient stay in a hospital in which the necessary medical care for the person being cared for, including the necessary follow-up treatment, is ensured.

These new regulations came into force on July 22, 2017.

If there are no particular hazards and the patient is simply no longer able to grasp the scope of his decision or to bring about an orderly intellectual decision-making process, these patients must be provided with care for compulsory treatment in accordance with the care law of the BGB. In urgent cases, provisional support can be provided through an interim order from a court (so-called emergency support). The aim of the care law is to bring about a decision about medical treatment for an adult if the adult cannot make his own decision due to limitations in judgment and control. The values of the patient count and not those of the patient representative or the care judge. The presumed will of the patient based on his or her values must be determined. The patient can therefore determine in advance by means of an advance directive that certain compulsory treatments may not be carried out in the context of care in the event of an illness-related inability to consent. It is also possible to reject all compulsory care under childcare law in this way (dispute). According to Section 1901a (2) BGB, the applicability of a living will must be checked by the legal guardian to determine whether it corresponds to the current living and treatment situation.

Mental Illness Laws

If the patient poses a danger to others or to himself, the laws for mental illnesses or accommodation laws of the federal states regulate whether accommodation and possible forced treatment are permissible.

Forced treatment in the penal system

For patients who have already committed a criminal offense due to illness and were admitted to a psychiatric clinic as a result of this offense, compulsory treatment of the illness that gave rise to the offense can be given. In this case, the regulations in the laws governing the execution of measures apply with regard to compulsory treatment.

With regard to compulsory treatment for the long-term restoration of the ability to discharge in the penal system, the Federal Constitutional Court demands:

- timely announcement of the planned treatment

- Order and supervision by a doctor

- adequate documentation

- Review of the measure in a secure independence from the accommodation facility before the compulsory treatment

- Forced treatment measure must be promising

- no milder, equally effective treatment agent is available

- Previously, based on trust, an attempt was made to gain natural consent.

- The burdens caused by the compulsory treatment are proportionate to the expected benefit

After its decision 2 BvR 882/09 from 2013, the Federal Constitutional Court left the question open for a long time as to whether the strict provisions in connection with the execution of measures also apply to compulsory treatment in the context of placement under state law. In the context of a constitutional complaint (BVerfG, decision of the Second Senate of July 19, 2017, AZ .: 2 BvR 2003/14), the Federal Constitutional Court decided that the provisions developed for compulsory treatment in the penal system should be transferred to compulsory treatment in the context of public law placement are.

No compulsory treatment according to the Infection Protection Act

To combat communicable diseases, such as open tuberculosis, the health department can order isolation ( quarantine ) in a hospital ( Section 30 (1 ) IfSG ), and under the conditions of Section 30 (2) IfSG also in a closed ward. In Germany, the Parsberg District Hospital , in particular, accepts tuberculosis patients who do not voluntarily isolate themselves, particularly due to mental illness. However, the IfSG does not provide for compulsory treatment of tuberculosis ( Section 28 (1) sentence 3 IfSG). Done with the secretion by the health department at the same time a housing by court decision, in addition to the psychiatric treatment as well as the compulsory treatment of physical underlying disease permitted.

Interventions according to the code of criminal procedure

According to Section 81a of the Code of Criminal Procedure, an accused must tolerate the taking of blood samples and physical interventions if these are important for the procedure.

Performing compulsory treatment

If a patient is not or no longer able to give consent, the following people can carry out compulsory treatment without or against the will of the patient:

- Supervisors can apply for compulsory treatment against the will of the supervised person and have it approved.

- Regulatory authorities or the police can arrange for compulsory treatment based on the laws for mentally ill patients and state accommodation laws. This may be necessary to avert danger in the event of danger to oneself or others.

- Judge by judicial approval of compulsory treatment for a person under care, only within the limits of § 1846 BGB if the legal custodian is prevented, otherwise at the request of the legal custodian, but also with regard to the execution of measures to restore the ability to be discharged in the long term.

- The emergency doctor and rescue service can, under certain circumstances, fall back on the general duty to provide assistance under Section 323c StGB and the justifying and supra-legal emergency . If the patient is unconscious, it can be assumed that the patient would like to get well. The doctor then acts as part of the management without an order .

- In urgent cases and in the case of vitally indicated measures, the doctor / psychiatry can be solely responsible for the compulsory treatment, since he can assume the patient's presumed consent until proven otherwise . Likewise, the doctor can carry out compulsory treatment in acute dangerous situations if official bodies or legal representatives of the patient are not available quickly enough and the requirements of the PsychKG are met. A subsequent judicial authorization is only necessary in these acute cases if the compulsory medication is continued. Apart from these special cases, the doctor usually has to inquire before performing compulsory treatment on a patient who is incapable of giving consent whether another person is legally entitled to consent to the treatment in place of the patient who is incapable of giving consent. Furthermore, the doctor must check whether an accommodation according to the mental health laws or state accommodation laws or an accommodation according to care law is necessary. If there is a decision by a judge, the doctor can refer to it with regard to the compulsory treatment.

- Persons entitled to custody, such as parents, can apply for compulsory placement and compulsory treatment for their children at the competent family court of the place of residence due to their medical care and the right to determine the residence. In the event of inactivity and vital threats to the child, the youth welfare office can initiate care and a later clarification by the family court. A supervisor must be appointed after the age of 18.

- An authorized representative can replace the will of the patient who is incapable of giving consent if the patient has previously given them a written health power of attorney while they are still able to give consent . This applies to both the implementation of coercive measures and the refusal to take coercive measures.

- Living Will: It belongs to the self-determination of every individual, regardless of the type and stage of disease in the case of his consent inability in a living will be specified in writing, at the time when not yet imminent investigations of his health, medical treatments or medical procedures to prohibit ( § 1901a , para. 1 and 3, Section 126 (1) BGB ). A legal guardian must also enforce a living will (Section 1901a, Paragraph 1, Clause 2 BGB). A psychiatric will cannot prevent placement and compulsory treatment in the event of exposure to others .

Legal basis in Austria

Since January 1, 1990, the so-called “placement without request”, ie forced admission and detention of patients against or without their will, has been regulated in the Accommodation Act (UbG).

The compulsory examination, compulsory treatment and force-feeding of prisoners is permissible according to § 69 StVG.

Legal basis in Switzerland

Medical treatment during the welfare placement is regulated in Art. 433 ff. ZGB .

Art. 434 ZGB reads:

- If the person concerned does not consent, the head physician of the department can order the medical measures provided for in the treatment plan in writing if:

- if the person concerned is not treated, there is a risk of serious damage to their health or the life or physical integrity of third parties is seriously endangered;

- the person concerned is incapable of discerning his or her need for treatment; and

- no adequate measure is available that is less drastic.

- The order will be communicated in writing to the person concerned and their confidant, together with instructions on legal remedies.

Art. 435 ZGB:

- In an emergency situation, the essential medical measures to protect the person concerned or third parties can be taken immediately.

- If the institution knows how the person wants to be treated, their wishes will be taken into account.

numbers

The Federal Ministry of Justice estimates that around 1,000 mentally handicapped girls were sterilized annually in West Germany - until the Care Act was changed in 1992 . In 2004, 187 license applications were submitted in the Federal Republic of Germany in accordance with Section 1905 (2) BGB, 154 of which were approved.

In the context of a hearing on the law to change the material admissibility requirements for compulsory medical measures and to strengthen the right of self-determination of those receiving care on April 26, 2017 in the German Bundestag, the expert Gudrun Schliebener, who is the chairwoman of the Federal Association of Relatives of Mentally Ill People, gave a statement. Schliebener criticized the lack of reliable figures on the extent of forced treatment in Germany. She therefore called for the establishment of a nationwide register of coercive measures.

criticism

The criticism, especially from those affected by associations, is particularly focused on the forced medication.

Affected associations point out that the prescribing practice of psychotropic drugs in psychiatry also depends on advertising and lobbying by pharmaceutical companies. In their advertising and lobbying, the pharmaceutical companies followed their own profit in the billions and not the patient benefit. Known side effects would not be published or belittled by the pharmaceutical companies and instead an exaggerated expectation of salvation would be generated from the psychotropic drugs advertised.

At the same time, the treating psychiatrist would also have a self-interest in administering psychotropic drugs as early as possible and possibly against the patient's will. Forced medication means that patients in crisis situations can be cared for and treated in a confined space while minimizing costs and with fewer staff. On the other hand, there would be a defenseless and locked up patient who could easily be accused of either lack of insight into the illness or inability to consent, or endangerment to others or himself on the part of the treating doctors.

Against this background, in the opinion of the affected associations, it would still be too easy, despite the legal hurdles, to carry out compulsory medication in psychiatry and also to invoke an alleged patient benefit. Instead, the compulsory medication serves the interests of the profit-oriented pharmaceutical companies or the interests of the profit-oriented doctor or the interests of an annoyed or insecure family member, but not the patient's welfare.

On the other hand, the associations concerned criticize the fact that every forced intervention in one's own body is experienced as physical harm and is a humiliating, degrading, shocking and frightening experience for the person concerned, which can lead to severe and long-lasting emotional suffering. This fact would not receive enough attention in the decision-making process of physicians who use coercive treatment.

The associations concerned point out that medication that appears to be voluntary, but which in reality was brought about under threat of coercive measures or other evils, represents a type of compulsory treatment.

In addition to portraying a positive, proud handling of mental disorders, criticism of forced treatment is also regularly the subject of Mad Pride events.

Results and validation of compulsory treatment

The effects and results of psychiatric coercive measures were examined by the EUNOMIA study . The interim results of the study carried out in ten European countries (Germany, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Poland, Spain, Italy and Greece) in the time frame from 2003 to 2005 showed that patients who are treated against their will in psychiatry , have a significantly worse prognosis for improvement than patients who are treated with their will.

See also

- Accommodation , accommodation (Germany)

- Forced sterilization

- Contraception

- Force-feeding

- History of Psychiatry

Web links

- Central ethics committee at the German Medical Association

- Compulsory treatment in custody law

- Federal Working Group on Psychiatry Law: The legal 1 x 1 of compulsory treatment (PDF; 175 kB)

- Law and Psychiatry, Supervision Court Day e. V. (PDF; 526 kB)

- History (SWR.de)

- Antipsychiatrie-Verlag (PDF; 108 kB) Overview lecture

- Violence and coercion in inpatient psychiatry (PDF; 1.4 MB) Aktion Psychisch Krankke e. V.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Magdalena Frühinsfeld: Brief outline of psychiatry. In: Anton Müller. First insane doctor at the Juliusspital in Würzburg: life and work. A short outline of the history of psychiatry up to Anton Müller. Medical dissertation Würzburg 1991, p. 9–80 ( Brief outline of the history of psychiatry ) and 81–96 ( History of psychiatry in Würzburg to Anton Müller ), p. 70.

- ↑ Erwin H. Ackerknecht : Brief history of psychiatry. Enke, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-432-80043-6 ; P. 34 f.

- ↑ a b Helmut Siefert: The forced chair. An example of how the mentally ill were dealt with in Haina in the 19th century. In: W. Heinemeyer, T. Plünder (Ed.): 450 years of psychiatry in Hesse. Publications of the Historical Commission for Hesse (47). Elwert publishing house. Marburg 1983, pp. 309-320 ( geschichtsverein-bademstal.de PDF).

- ^ Melchior Josef Bandorf: Hayner, Christian August Fürchtegott . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 11, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1880, p. 164 f.

- ↑ geb.uni-giessen.de (PDF).

- ↑ Heinz Schott, Rainer Tölle: History of psychiatry: disease teachings, wrong ways, forms of treatment. C. H. Beck, 2006, ISBN 978-3-406-53555-0 ( Google Books )

- ↑ Groos: Two observations on the effect of red-hot iron on the mad. In: Journal for Psychic Doctors . Volume 4, Issue 4, 1821 p. 119.

- ↑ emedicine.medscape.com

- ↑ Klaus Dörner : Citizens and Irre, on the social history and sociology of science of psychiatry. [1969] Fischer Taschenbuch, Bücher des Wissens, Frankfurt am Main 1975, ISBN 3-436-02101-6 ; Cape. II Great Britain, para. 3 Reform movement and the dialectic of coercion, p. 80.

- ↑ Asmus Finzen : The Pinel pendulum. The dimension of the social in the age of biological psychiatry. Edition Das Narrenschiff im Psychiatrie-Verlag, Bonn 1998, ISBN 3-88414-287-9 ; P. 10 ff.

- ↑ F. Kohl: Philippe Pinel and the legendary "chain liberation" at the Paris hospitals Bicêtre (1793) and Salpêtrière (1795). Part II: Historical backgrounds, allegorical representations and disciplinary genetic myths. Psychiatr. Practice. 23 (1996), pp. 92-97

- ↑ M. Müller: Memories. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg 1981.

- ↑ Johann Christian Reil : Rhapsodies about the application of the psychic spa method on mental disruptions. Hall 1803, p. 26 and 49 f.

- ↑ The new law on help and protective measures for mental illnesses in North Rhine-Westphalia . Medical Association of North Rhine (corporation under public law). February 28, 2017. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ↑ of March 23, 2011 Press release of the Federal Constitutional Court of April 15, 2011 on the Rhineland-Palatinate Measures Act.

- ↑ Federal Constitutional Court, decision of March 23, 2011, Az. 2 BvR 882/09

- ↑ and from October 12, 2011 decision of the Federal Constitutional Court on the Baden-Württemberg law on the accommodation of the mentally ill

- ↑ of June 20, 2012 in two proceedings for the area of care law BGH, decision of June 20, 2012 , Az. XII ZB 99/12 and BGH, decision of June 20, 2012 , Az. XII ZB 130/12, full text.

- ↑ Plenary minutes 17/217 p. 154 (D) (PDF; 2.6 MB)

- ↑ Changes to § 1906 BGB BT-Drucksache 17/12086 (PDF; 255 kB)

- ↑ Federal Ministry of Justice: Compulsory treatment, exception regulation for emergency situations (bmj.de)

- ↑ a b c Amendment to the law on health care proxy and care . Federal Chamber of Notaries. Archived from the original on October 26, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ^ A b c Marc Petit, Jan Philipp Klein: Topics of the time: Mentally ill: Forced treatment possible again with judicial approval . In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt . 110th year, issue 9. Deutscher Ärzteverlag, March 1, 2013, p. A 377 - A 379 ( aerzteblatt.de [PDF]).

- ↑ a b lexetius.com

- ↑ Federal Constitutional Court, decision of July 26, 2016, Az. 1 BvL 8/15

- ↑ Sebastian Janning: Order of the Federal Constitutional Court on compulsory medical treatment (AZ des LWL: 65 RS 4 2 - 12) (PDF) Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe (LWL): LWL Department for Hospitals and Health Care. August 30, 2016. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved on May 3, 2017.

- ↑ Federal Ministry of Justice and for Consumer Protection: draft bill of the Federal Ministry of Justice and for consumer protection draft of a law to change the material admissibility requirements of medical coercive measures and to strengthen the self-determination of those in care. ( bmjv.de PDF).

- ↑ Printed matter 18/11240: Draft of a law to change the material admissibility requirements of compulsory medical measures and to strengthen the self-determination of those in care (PDF) German Bundestag. February 20, 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- ↑ Closing of the loophole in the regulation of the compulsory treatment of those in care (source: Current reports from the Bundestag (hib), No. 110/2017) . Journal for the entire family law (FamRZ). February 23, 2017. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved on May 3, 2017.

- ↑ Law to change the material admissibility requirements for compulsory medical measures and to strengthen the self-determination of those in care

- ↑ Printed matter 18/12842: Recommendation for a resolution and report by the Committee on Legal Affairs and Consumer Protection (6th Committee) on the draft law of the Federal Government - Printed matter 18/11240, 18/11617, 18/11822 No. 5 - Draft law to change the material admissibility requirements of coercive medical measures and to strengthen the right of self-determination of those receiving care (PDF) German Bundestag. June 21, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ↑ Basic information about the process with the ID 18-79586 - Legislation: Act to change the material admissibility requirements for coercive medical measures and to strengthen the self-determination of those in care . German Bundestag. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ↑ Changes by the law to change the material admissibility requirements for compulsory medical measures and to strengthen the self-determination of those in care

- ↑ a b c d e f Plenary minutes 18/240: Shorthand report of the 240th meeting in Berlin on Thursday, June 22, 2017, pages 24679 to 24683 (PDF) German Bundestag. June 22, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ↑ a b c d Comparison of § 1906 BGB old version with § 1906a BGB new version

- ↑ Bundestag: loophole in the law on compulsory treatment closed , Ärzte Zeitung online. June 23, 2017. Archived from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ A b c Robert von Cube: Even more forced treatment? . June 23, 2017. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ↑ Forced treatment: BGH emphasizes the crucial role of the doctor (Federal Court of Justice, decision of January 14, 2015, Az .: XII ZB 470/14) , ÄrzteZeitung. February 11, 2015. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved on August 19, 2017.

- ↑ BGH ruling of January 14, 2015 Az. XII ZB 470/14 . Openjur . Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved on August 19, 2017: "Leitsatz Openjur :" Does not contain any information on the implementation and documentation of this measure under the responsibility of a doctor when consenting to a compulsory medical measure is approved or when it is ordered , the order is altogether unlawful and the rights of the person concerned are violated (following the Senate decision of June 4, 2014 - XII ZB 121/14 - FamRZ 2014, 1358). ""

- ↑ Jurisprudence on psychiatric assessment: The review of a measure presupposes a secure independence from the accommodation facility to BVerfG, 2 BvR 228/12 of February 20, 2013, paragraph no. (1–76), here paragraph 71 . Internet publication for general and integrative psychotherapy: news from psychiatry and the environment. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved on August 19, 2017: "Rn 71:" Contrary to the constitutional requirements, a prior review of the measure in secure independence from the accommodation facility (see BVerfGE 128, 282 <315 ff. >; 129, 269 <283>). The necessary check is not ensured in particular by the fact that, according to Section 22, Paragraph 1, Clause 1 of the SächsPsychKG, the treatment of an inmate that does not take place with his or her own consent, basically the consent of the legal representative In addition to other possible solutions, such as a judge's reservation or the involvement of another neutral body (cf. BVerfGE 128, 282 <316>), the involvement of a supervisor is also fundamentally one of the possible solutions Possibilities of the necessary prior external review, provided that the right to care itself the s allows. However, the regulation made in Section 22, Paragraph 1, Clause 1 of the SächsPsychKG does not initially provide for such a review, regardless of the legal questions relating to childcare that it raises. By binding the admissibility of compulsory treatment solely to the existence of the consent of the legal representative, the regulation does not assign the latter the function of reviewing a decision of the clinic to determine whether it complies with the prescribed legal standards. Rather, it puts the supervisor's decision in place of such standards. This is therefore not an external control in the sense of the requirement of a prior review of the measure with a secure independence from the accommodation facility. The lack of material criteria for the admissibility of compulsory treatment (above BI3b) bb) (1)) thus at the same time deprives the procedural approach of the contested law of the legitimation function intended for it. ""

- ↑ Federal Constitutional Court BVerfG, decision of February 20, 2013, Az. 2 BvR 228/12

- ^ Higher Regional Court of Karlsruhe, order of November 12, 2015, Az. 9 U 78/11

- ↑ Judgment on forced placement: risk prognosis must be watertight , Ärzte Zeitung. December 3, 2015. Archived from the original on December 12, 2015. Retrieved on July 29, 2017.

- ↑ Karlsruhe Higher Regional Court: Complainant receives EUR 25,000 in compensation for unlawful placement in a psychiatric clinic . Justice in Baden-Württemberg. November 19, 2015. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved on July 29, 2017.

- ^ Higher Regional Court of Karlsruhe, order of November 12, 2015, Az. 9 U 78/11 . Jurion . November 12, 2015. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of the Second Senate of July 19, 2017 - 2 BvR 2003/14 - Rn. (1-47), here paragraph 42 . Federal Constitutional Court. August 16, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ↑ a b BVerfG: Mentally Ill Act unconstitutional - compulsory medical treatment not permitted . haufe.de. August 31, 2017. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ↑ Günther Fißlthaler, Peter Sönser: Forced detention and forced treatment in Austria. An experience report on the Federal Act of March 1, 1990. In: Kerstin Kempker, Peter Lehmann (Ed.): Instead of Psychiatrie 2. Peter Lehmann Antipsychiatrieverlag, Berlin 1993, pp. 195–207

- ^ Report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) to the Austrian Government on its visit to Austria from September 22 to October 1, 2014 Council of Europe, November 6, 2015, p. 53

- ^ Psychiatry: The days of net beds are over Die Presse , July 1, 2015

- ↑ BGE 125 III 169 f.

- ↑ Forced admissions to psychiatry from a fundamental rights perspective. from humanrights.ch February 17, 2014, accessed on November 12, 2018

- ↑ Federal Supreme Court, judgment of May 18, 2017, Az. 5A 255/2017

- ↑ United Nations Human Rights Council: Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Juan E. Méndez; A / HRC / 22/53, paragraph 35 and 65.f. ( ohchr.org PDF).

- ↑ United Nations Human Rights Council: Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Juan E. Méndez; A / HRC / 22/53 , paragraph 32 ( ohchr.org PDF).

- ↑ United Nations Human Rights Council: Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General. Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Mental health and. Advance edited version ( ohchr.org PDF, of July 24, 2018; Article 46).

- ↑ Birgit Hoffmann: Criminal responsibility for failing to protect consenting (in) capable adults. Contributions of the 12th Guardianship Court Day 4. – 6. November 2010 in Brühl ( bgt-ev.de PDF, accessed on December 29, 2015).

- ↑ Wolf-Dieter Narr , Thomas Saschenbrecker: Inquired - the reform of compulsory treatment with neuroleptics in the practice of supervisory courts . 2015.

- ^ Marc Petit, Jan Philipp Klein: Mentally Ill: Forced treatment possible again with judicial approval. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. Volume 110, 2013, pp. A-377.

- ↑ cf. for Lower Saxony: Osnabrück District Court rejects the effectiveness of an advance directive against compulsory treatment in certain cases. Press release of LG Osnabrück 3/20 from January 15, 2020 (sexually disinhibited and aggressive behavior towards third parties).

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of the Second Senate of March 23, 2011 - 2 BvR 882/09 - Rn. (1–83), here paragraphs 62 to 73 . Federal Constitutional Court. March 23, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of the Second Senate of July 19, 2017 - 2 BvR 2003/14 - Rn. (1-47), here paragraphs 26 to 35 . Federal Constitutional Court. July 19, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ↑ Merle Schmalenbach: Magic mountain behind barbed wire. A clinic in Bavaria treats tuberculosis sufferers who resist therapy - and locks them up for it. In: The time. January 30, 2014.

- ^ Tuberculosis Clinic: Forced quarantine on the "Magic Mountain" Der Spiegel , March 22, 2012.

- ^ LG Osnabrück, decision of January 10, 2020 - 4 T 8/20 - 4 T 10/20 = NJW 2020, 1687

- ↑ § 69 StVG

- ↑ Swiss Competence Center for Human Rights (SKMR): Caring placement and forced treatment. The new adult protection law in the light of the provisions of the ECHR. Accessed in 2017.

- ↑ Anke Engelmann: When two love each other. In: Publik-Forum , No. 12, 2009 ( poesiebuero.de ; PDF; 2.1 MB).

- ↑ Federal Ministry of Justice: Special survey on the procedure under the Care Act. ( bundesanzeiger-verlag.de PDF).

- ↑ Looking for barriers to compulsory treatment . German Bundestag. April 27, 2017. Archived from the original on February 5, 2018. Retrieved on February 5, 2018.

- ↑ zwangspsychiatrie.de (PDF).

- ^ Gerd Laux : Pharmakopsychiatrie . Gustav Fischer, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-437-00644-4