Causes of World War II

Template:WorldWarIISegmentUnderInfoBox

The culmination of events that led to World War II are generally understood to be the 1939 invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany and of the Republic of China by the Empire of Japan. These military aggressions were the decisions made by authoritarian ruling elites in Germany and Japan. World War II started after these aggressive actions were met with an official declaration of war and/or armed resistance.

Anti-Communism

Template:Associated main The October Revolution led many Germans to fear that a Communist revolution would occur in their own country.

Shortly after World War I, the Communists attempted to seize power in the country, leading to the establishment of the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic. The Freikorps helped to put down the rebellion and their forces were an early component of the Nazi Party.

Expansionism

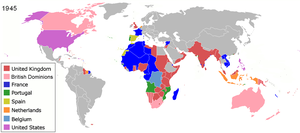

Expansionism is the doctrine of expanding the territorial base (or economic influence) of a country, usually by means of military aggression. In Europe, Italy’s Mussolini sought to create a New Roman Empire based around the Mediterranean and invaded Albania in early 1939, start of the war, and later invaded Greece. Italy had also invaded Ethiopia as early as 1935. This provoked little response from the League of Nations and the former Allied powers, a reaction to empire-building that was common throughout the war-weary and depressed economy of the 1930s. Germany came to Mussolini's aid on several occasions. Italy’s expansionist desires can be tied to bitterness over minimal gains after helping the Allies achieve victory in World War I. At Versailles, Italy had been promised large chunks of Austrian territory but received only Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, and promises believed to have been made about Albania and Asia Minor were ignored by the more powerful nations' leaders.

After World War I, the German state had lost land to Lithuania, France, Poland, and Denmark. Notable losses included the Polish Corridor, Danzig, the Memel Territory (to Lithuania), the Province of Posen, the French province of Alsace-Lorraine , and the most economically valuable eastern portion of Upper Silesia. The economically valuable regions of the Saarland and the Rhineland were placed under the authority (but not jurisdiction) of France. Majority of those territories were inhabited by non-Germans.

The result of this loss of land was population relocation, bitterness among Germans, and also difficult relations with those in these neighboring countries, contributing to feelings of revanchism which inspired irredentism. Under the Nazi regime, Germany began its own program of expansion, seeking to restore the "rightful" boundaries of pre-World War I Germany, resulting in the reoccupation of the Rhineland and action in the Polish Corridor, leading to a perhaps inevitable war with Poland. However, because of Allied appeasement and prior inaction, Hitler estimated that he could invade Poland without provoking a general war or, at the worst, only spark weak Allied intervention after the result was already decided.

Also of importance was the idea of a Greater Germany, where supporters hoped to unite the German people under one nation, which included all territories where Germans lived, disregarding the fact of them being minority in this territory. Germany's pre-World War II ambitions in both Austria and parts of Czechoslovakia mirror this goal. After the Treaty of Versailles, an Anschluss, or union, between Germany and a newly reformed Austria was prohibited by the Allies. Such a plan of unification, predating the creation of the German State of 1871, had been discarded because of the Austro-Hungarian Empire's multiethnic composition as well as competition between Prussia and Austria for hegemony. At the end of World War I, the majority of Austria's population supported such a union.

The Soviet Union had lost large parts of former Russian Empire territories to Poland, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Romania in World War I and the Russian Civil War and was interested in regaining lost territories. Also during the Russo-Japanese war some territories had been lost to Japan.

Hungary, an ally of Germany during World War I, had also been stripped of enormous territories after the partition of the Austria-Hungary empire and hoped to regain those lands by allying with Germany. Greater Hungary was a popular topic of discussion.

Romania, while on the winning side in World War I, found itself on the losing side in early stages of World War II. As result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina were ceded to the Soviet Union; the Second Vienna Award resulted in the loss of Northern Transylvania to Hungary, and the Treaty of Craiova resulted in the return of Southern Dobruja to Bulgaria. Greater Romania was a concept that caused Romania to side more and more with Nazi Germany.

Bulgaria, also an ally of Germany during World War I, had lost territories to Greece, Romania, and Yugoslavia in World War I and the Second Balkan War.

Finland lost territory to the Soviet Union during the early stages of World War II in the lop-sided Winter War. When Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in 1941, Finland was drawn into what was called the Continuation War to regain what it had lost.

In Asia, Japan harbored expansionist desires, fuelled at least partially by the minimal gains the Japanese saw after World War I. Despite having taken a German colony in China and a few other Pacific islands, as well as swaths of Siberia and the Russian port of Vladivostok, Japan was forced to give up all but the few islands it had gained during World War I.

Thailand had lost territories to France and the United Kingdom in the end of 19th century and at the beginning of 20th century, and wanted to regain those areas.

In many of these cases, the roots of the expansionism leading to World War II can be found in perceived national slights resulting from previous involvement in World War I, nationalistic goals of re-unification of former territories or dreams of an expanded empire.

Fascism

Template:Associated main Fascism is a philosophy of government that is marked by stringent social and economic control, a strong, centralized government usually headed by a dictator, and often has a policy of belligerent nationalism that gained power in many countries across Europe in the years leading up to World War II. In general, it believes that the government should control industry and people for the good of the country.

In many ways, fascism viewed the army as a model that a whole society should emulate. Fascist countries were highly militaristic, and the need for individual heroism was an important part of fascist ideology. In his book The Doctrine of Fascism, Benito Mussolini declared that "fascism does not, generally speaking, believe in the possibility or utility of perpetual peace".[2] Fascists believed that war was generally a positive force for improvement and were therefore eager at the prospect of a new European war. Fascism ultimately proved to be one of beliefs that was universal with many invading Axis countries.

Isolationism

Template:Associated main Isolationism was the dominant foreign policy of the United States following World War I. Although the U.S. remained active in the Western Hemisphere and the Pacific, it withdrew from European political affairs but retained strong business connections.

Popular sentiment in Britain and France was also isolationist and very war weary after the slaughter of World War I. In reference to Czechoslovakia, Neville Chamberlain said, "How horrible, fantastic it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas-masks here because of a quarrel in a far away country between people of whom we know nothing. I am myself a man of peace from the depths of my soul."

Within a few years of this statement, the world was engulfed in total war.

Militarism

Template:Associated main A highly militaristic and aggressive attitude prevailed among the leaders of Germany, Japan and Italy. Compounding this fact was the traditional militant attitude of the three had a similar track record that is often underestimated. For example, Germany introduced permanent conscription in 1935, with a clear aim of rebuilding its army (and defying the Treaty of Versailles).

Nationalism

Nationalism is the belief that groups of people are bound together by territorial, cultural and ethnic links. Nationalism was used by their leaders to generate public support for German, Italian and Japanese aggression. Fascism in these countries was built largely upon a theory of nationalism and the search for a cohesive "nation state". Hitler and his Nazi Party used nationalism to great effect in Germany, already a nation where fervent nationalism was prevalent. In Italy, the idea of restoring the Roman Empire was attractive to many Italians. In Japan, nationalism, in the sense of duty and honor, especially to the emperor, had been widespread for centuries.

Racism

Twentieth-century events marked the culmination of a millennium-long process of intermingling between Germans and Slavs. Over the years, many Germans had settled to the east (the Volga Germans). Such migratory patterns created enclaves and blurred ethnic frontiers. By the 19th and 20th centuries, these migrations had acquired considerable political implications. The rise of the nation-state had given way to the politics of identity, including Pan-Germanism and Pan-Slavism. Furthermore, Social-Darwinist theories framed the coexistence as a "Teuton vs. Slav" struggle for domination, land and limited resources. Integrating these ideas into their own world-view, the Nazis believed that the Germans, the "Aryan race", were the master race and that the Slavs were inferior. During World War II, Hitler used racism against "Non-Aryan" peoples.

Interrelations and economics

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was neither lenient enough to appease Germany, nor harsh enough to prevent it from becoming the dominant continental power again.

The treaty placed the blame, or "war guilt" on Germany and Austria-Hungary, and punished them from their "responsibility" rather than working out an agreement that would assure peace in the long-term future. The treaty resulted in harsh monetary reparations, territorial dismemberment, mass ethnic resettlements and indirectly hampered the German economy by causing rapid hyperinflation - see inflation in the Weimar Republic. The Weimar Republic printed trillions to help pay off its debts and borrowed heavily from the United States (only to default later) to pay war reparations to Britain and France, who still carried war debt from World War I.

The treaty created bitter resentment towards the victors of World War I, who had promised the people of Germany that U.S. President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points would be a guideline for peace; many Germans felt that the German government had agreed to an armistice based on this understanding, while others felt that the German Revolution had been orchestrated by the "November criminals" who later assumed office in the new Weimar Republic. Wilson was not able to get the Allies to agree to adopt them, nor could he persuade the U.S. Congress to join the League of Nations.

Contributing to this, the Allies did not occupy any part of Germany, with the Western front having been in France for years. Only the German colonies were taken during the war, and Italy took South Tyrol after an armistice had been agreed upon. The war in the east ended with the collapse of Russian Empire, and German troops occupied (with varying degree of control) large parts of Eastern and Central Europe. The Kaiserliche Marine spend most of the war in port, only to be turned over and scuttled. The lack of an obvious military defeat was one of the pillars that held together the Dolchstosslegende and gave the Nazis another tool at their disposal.

An opposite view of the treaty held by some is that it did not go far enough in permanently neutering the capability of Germany to be a great power by dividing Germany into smaller, less powerful states. In effect, this would have undone Bismarck's work and would have accomplished what the French delegation at the Paris Peace Conference wanted. However, this could have had any number of unforeseeable consequences, especially amidst the rise of communism. Regardless, the Treaty of Versailles is generally agreed to be a very poor treaty which helped the rise of the Nazi Party.

Competition for resources

Other than a few coal and iron deposits, Japan lacks true natural resources. Japan, the only Asian country with a burgeoning industrial economy at that time, feared that a lack of raw materials might hinder its ability to fight a total war against a reinvigorated Soviet Union. In the hopes of expanding its resources, Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931 and set about to consolidate its resources and develop its economy. Insurgency by nationalists south of Manchuria compelled the Japanese leaders to argue for a brief, three month war to knock out Chinese power from the north. When it became clear that this time estimate was absurd, plans for obtaining more resources began. The Imperial Navy eventually began to feel that it did not have enough fuel reserves.

To remedy this deficiency and ensure a safe supply of oil and other critical resources, Japan would have to challenge the European colonial powers over the control of oil rich areas such as the Dutch East Indies. Such a move against the colonial powers was however expected to lead to open conflict also with the United States. On August 1941, the crisis came to a head as the United States, which at the time supplied 80% of Japanese oil imports, initiated a complete oil embargo. This threatened to cripple both the Japanese economy and military strength once the strategic reserves would run dry. Faced with the choice of either trying to appease the U.S., negotiate a compromise, find other sources of supply or go to war over resources, Japan chose the last option. Hoping to knock out the U.S. for long enough to be able to achieve and consolidate their war-aims, the Japanese Navy attacked the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. They mistakenly believed they would have about a two year window to consolidate their conquests before the United States could effectively respond and that the United States would compromise long before they could get anywhere near Japan.

League of Nations

Template:Associated main The League of Nations was an international organization founded after World War I to prevent future wars. The League's methods included disarmament; preventing war through collective security; settling disputes between countries through negotiation diplomacy; and improving global welfare. The diplomatic philosophy behind the League represented a fundamental shift in thought from the preceding hundred years. The old philosophy, growing out of the Congress of Vienna (1815), saw Europe as a shifting map of alliances among nation-states, creating a balance of power maintained by strong armies and secret agreements. Under the new philosophy, the League was a government of governments, with the role of settling disputes between individual nations in an open and legalist forum. The impetus for the founding of the League came from U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, though the United States never joined. This also lessened the power of the League—the addition of a burgeoning industrial and military world power would have added more force behind the League's demands and requests.

The League lacked an armed force of its own and so depended on the members to enforce its resolutions, keep to economic sanctions which the League ordered, or provide an army, when needed, for the League to use. However, they were often very reluctant to do so.

After numerous notable successes and some early failures in the 1920s, the League ultimately proved incapable of preventing aggression by the Axis Powers in the 1930s. The absence of the U.S., the reliance upon unanimous decisions, the lack of an armed force, and the continued self-interest of its leading members meant that this failure was arguably inevitable.

The Great Depression

Fallout from the collapse of the United States economy following the 1929 Stock Market Crash reverberated throughout the world. European countries, especially Germany, were hit hard by the Great Depression, which led to high rates of unemployment, poverty, civil unrest, and an overall feeling of despair that led to the rise of Adolf Hitler and other militaristic fascists.

European Civil War

Some academics examine World War II as the final portion of a wider European Civil War that began with the Franco-Prussian War in July 19, 1870. The proposed period would include many (but not all) of the major European regime changes to occur during the period, including those during the Spanish Civil War and Russian Civil War.

Specific events

Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War was initiated by Napoleon III of France, who was alarmed at the rapid growth in population and unity among the German people and was eventually forced to declare war. This period marked a relative decline in the strength of France, which continued into the 20th century.

The war ended with a Prussian victory, and Germany unified soon after. Alsace-Lorraine, a border territory, was transferred from France to Germany. The resulting disruption in the balance of power led France to seek alliances with Russia and the United Kingdom.

World War I

Due to the fact that World War I lacked a dramatically decisive conclusion, many people view the Second World War as a continuation of the first. Allied troops had not entered Germany, and its people anticipated a treaty along the lines of the Fourteen Points. This meant the German people argued that had the "traitors" not surrendered to the Allies, Germany could have gone on to win the war, however unlikely the reality. This peace proposal was largely abandoned in favor of punishing Germany for its alleged "war responsibility", an ineffective compromise that left Germany smaller, weaker and embittered, but capable of rebounding and seeking revenge.

Large groups of nationalistic minorities still remained trapped in other nations. For example, Yugoslavia (originally the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes) had 5 major ethnic groups (the Serbs, Croats, Macedons, Montenegrins, and the Slovenes), and it was created after the war. Other examples abound in the former lands of Austria-Hungary which were divided up quite arbitrarily and unfairly after the war. For example, Hungary was held responsible for the war and stripped of two thirds of its territory while Austria, which had been an equal partner in the Austro-Hungarian government, received the Burgenland after a plebiscite, while losing the Sudetenland and the part of Tyrol that makes up Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol.

The Germans had a difficult time accepting defeat. At the end of the war, the navy was in a state of mutiny, and the army was retreating (but not routing) in the face of an enemy with more men and material. Despite this reality, some Germans, notably Hitler, advanced the idea that the army would somehow have triumphed if not for the German Revolution at home. This "Stab in the Back" theory was used to convince the people that a second World war would be winnable.

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic governed Germany from 1919 to 1933. The republic was named after the city of Weimar, where a national assembly convened to produce a new constitution after the German Empire was abolished following the nation's defeat in World War I. It was a liberal democracy in the style of France and the United States.

The Beer Hall Putsch was a failed Nazi coup d'état which occurred in the evening of Thursday, November 8 to the early afternoon of Friday, November 9 1923. Adolf Hitler, using the popular World War I General Erich Ludendorff, unsuccessfully tried to overthrow the Weimar Republic.

Economic depression

The Great Depression resulted in 33% unemployment rate in Germany and a 25% unemployment rate in the U.S. This led many people to support dictatorships just for a steady job and adequate food.

The Great Depression hit Germany second only to the United States. Severe unemployment prompted the Nazi Party, which had been losing favor, to experience a surge in membership. This more than anything contributed to the rise of Hitler in Germany, and therefore World War II in Europe. After the end of World War I many American industries and banks invested their money in rebuilding Europe. This happened in many European countries, but especially in Germany. After the 1929 crash, many American investors fearing that they would lose their money, or having lost all their capital, stopped investing as heavily in Europe.

Nazi dictatorship

Template:Associated main Hitler was appointed chancellor on January 30, 1933. The arson of the parliament building on February 27 (which some have claimed the Nazis had instigated) was used as an excuse for the cancellation of civil and political liberties, enacted by the aged President Paul von Hindenburg and the rightist coalition cabinet led by Hitler.

After new elections, a Nazi-led majority abolished parliamentarism, the Weimar constitution, and practically the parliament itself through the Enabling Act on March 23, whereby the Nazis' planned Gleichschaltung ("bringing into line") of Germany was made formally legal, giving the Nazis totalitarian control over German society. In the "Night of the Long Knives", Hitler's men murdered his main political rivals. After Hindenburg died on August 2, 1934, the authority of the presidency fell into the hands of Adolf Hitler. Without much resistance from the army leadership, the Soldiers' Oath was modified into an oath of obedience to Adolf Hitler personally.

In violation of the Treaty of Versailles and the spirit of the Locarno Pact, Germany remilitarized the Rhineland on Saturday, March 7, 1936. The occupation was done with very little military force; the troops entered on bicycles and could easily have been stopped had it not been for the appeasement mentality. France could not act because of political instability at the time. In addition, since the remilitarization occurred on a weekend, the British Government could not find out or discuss actions to be taken until the following Monday. As a result of this, the governments were inclined to see the remilitarization as a fait accompli.

Italian invasion of Ethiopia

Template:Associated main Benito Mussolini attempted to expand the Italian Empire in Africa by invading Ethiopia, which had so far successfully resisted European colonization. With the pretext of the Walwal incident in September 1935, Italy invaded on October 3, 1935, without a formal declaration of war. The League of Nations declared Italy the aggressor but failed to impose effective sanctions.

The war progressed slowly for Italy despite its advantage in weaponry and the use of mustard gas. By March 31, 1936, the Italians won the last major battle of the war, the Battle of Maychew. Emperor Haile Selassie fled into exile on May 2, and Italy took the capital, Addis Ababa, on May 5. Italy annexed the country on May 7, merging Eritrea, Abyssinia and Somaliland into a single state known as Italian East Africa.

On June 30, 1936, Emperor Haile Selassie gave a stirring speech before the League of Nations denouncing Italy's actions and criticizing the world community for standing by. He warned that "It is us today. It will be you tomorrow". As a result of the League's condemnation of Italy, Mussolini declared the country's withdrawal from the organization.

Spanish Civil War

Template:Associated main Germany and Italy lent support to the Nationalist insurrection led by general Francisco Franco in Spain. The Soviet Union supported the existing government, the Spanish Republic which showed leftist tendencies. Both sides used this war as an opportunity to test improved weapons and tactics. The Bombing of Guernica was a horrific attack on civilians which foreshadowed events that would occur throughout Europe.

Second Sino-Japanese War

Template:Associated main The Second Sino-Japanese War began in 1937 when Japan attacked deep into China from its foothold in Manchukuo.

The invasion was launched by the bombing of many cities such as Shanghai, Nanjing and Guangzhou. The latest, which began on 22 and 23 September 1937, called forth widespread protests culminating in a resolution by the Far Eastern Advisory Committee of the League of Nations.

The Imperial Japanese Army captured the Chinese capital city of Nanjing, and committed brutal atrocities in the Nanjing massacre.

Anschluss

The Anschluss was the 1938 annexation of Austria into Germany. Historically, the idea of creating a Greater Germany through such a union had been popular in Austria as well as Germany, peaking just after World War I when both new constitutions declared German Austria a part of Germany. Such an action was expressly forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles, though. Nevertheless, Hitlerian Germany pressed for the Austrian Nazi Party's legality, played a critical role in the assassination of Austrian chancellor, Engelbert Dollfuss, and applied pressure for several Austrian Nazi Party members to be incorporated into offices within the Austrian administration.

Following a Hitler speech at the Reichstag, Dollfuss' successor, Kurt Schuschnigg, made it clear that he could be pushed "no further". Amidst mounting pressures from Germany, he elected to hold a plebiscite, hoping to retain autonomy. However, just days prior to the balloting, a successful Austrian Nazi Party coup transferred power within the country. The takeover allowed German troops to enter Austria as "enforcers of the Anschluss", since the Party quickly transferred power to Hitler. Consequently, no fighting occurred as most Austrian were enthusiastic, and Austria ceased to exist as an independent state. Britain, France and Fascist Italy, who all had vehemently opposed such a union, did nothing. Just as importantly, the quarrelling amongst these powers doomed any continuation of a Stresa Front and, with no choice but to accept the unfavorable Anschluss, Italy had little reason for continued opposition to Germany, and was if anything drawn in closer to the Nazis.

Munich Agreement

Template:Associated main The so-called Sudetenland was a predominantly German-speaking region along the Western borders of Czechoslovakia with Germany. Thus it contained most of the defensive system which ran across mountainous terrain and was larger than the Maginot line. The Sudetenland region also comprised about one third of Bohemia (western Czechoslovakia) in terms of territory, population, and economy. Czechoslovakia had a modern army of 38 divisions[citation needed], backed by a well-noted armament industry (Škoda) as well as military alliances with France and Soviet Union.

Hitler pressed for the Sudetenland's incorporation into the Reich, supporting German separatist groups within the Sudeten region. Alleged Czech brutality and persecution under Prague helped to stir up nationalist tendencies, as did the Nazi press. After the Anschluss, all German parties (except German Social-Democratic party) merged with the Sudeten German Party (SdP). Paramilitary activity and extremist violence peaked during this period and the Czechoslovakian government declared martial law in parts of the Sudetenland to maintain order. This only complicated the situation, especially now that Slovakian nationalism was rising, out of suspicion towards Prague and Nazi encouragement. Citing the need to protect the Germans in Czechoslovakia, Germany requested the immediate annexation of the Sudetenland.

In the Munich Agreement of September 30, 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and French leaders appeased Hitler. The conferring powers allowed Germany to move troops into the region and incorporate it into the Reich "for the sake of peace." In exchange for this, Hitler gave his word that Germany would make no further territorial claims in Europe.[1] Czechoslovakia, which at had already mobilized over one million troops and was prepared to fight, was not allowed to participate in the conference. When the French and British negotiators informed the Czechoslovak representatives about the agreement, and that if Czechoslovakia would not accept it, France and Britain would consider Czechoslovakia to be responsible for war, President Edvard Beneš capitulated. Germany took the Sudetenland unopposed.

In March 1939, breaking the Munich Agreement, German troops invaded Prague, and with the Slovaks declaring independence, the country of Czechoslovakia disappeared. The entire ordeal ended the French and British policy of appeasement and enabled Germany to grow stronger in Europe.

Italian invasion of Albania

Template:Associated main After German occupation of Czechoslovakia, Italy saw itself becoming a second-rate member of the Axis. Rome delivered Tirana an ultimatum on March 25, 1939, demanding that it accede to Italy's occupation of Albania. King Zog refused to accept money in exchange for countenancing a full Italian takeover and colonization of Albania. On April 7, 1939, Mussolini's troops invaded Albania. Albania was occupied after short campaign despite stubborn resistance offered by the Albanian forces.

Soviet-Japanese Border War

Template:Associated main In 1939, the Japanese attacked north from Manchuria into Siberia. They were decisively beaten by Soviet units under General Georgy Zhukov. Following this battle, the Soviet Union and Japan were at peace until 1945. Japan looked south to expand its empire, leading to conflict with the United States over the Philippines and control of shipping lanes to the Dutch East Indian. The Soviet Union focused on the west, leaving 1 million to 1.5 million troops to guard the frontier with Japan.

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Nominally, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression treaty between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. It was signed in Moscow on August 23, 1939, by the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop.

In 1939, neither Germany nor the Soviet Union were ready to go to war with each other. The Soviet Union had lost territory to Poland in 1920. Although officially labeled a "non-aggression treaty", the pact included a secret protocol, in which the independent countries of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Romania were divided into spheres of interest of the parties. The secret protocol explicitly assumed "territorial and political rearrangements" in the areas of these countries.

Subsequently all the mentioned countries were invaded, occupied or forced to cede part of their territory by either the Soviet Union, Germany, or both.

Invasion of Poland

Template:Associated main There is some debate towards the claim that Poland had in 1933 tried to get France to join it in preventive attack after Nazis won in Germany[2] Tensions had existed between Poland and Germany for some time in regards to the Free City of Danzig and the Polish Corridor. This had been settled in 1934 by a nonaggression pact but in spring of 1939, tensions rose again. Finally, after issuing several proposals, Germany declared that diplomatic measures had been exhausted, and shortly after the Hitler-Stalin pact had been signed, invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Britain and France had previously warned that they would honor their alliances to Poland and issued an ultimatum to Germany: withdraw or war would be declared. Germany declined, and what became World War II was declared by the British and French, without entering the war effectively. The Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east on September 17.

Final diplomatic strategy

In 1940, a trip to Italy was made by British amateur diplomat James Lonsdale-Bryans. The trip, which was arranged with the support of Lord Halifax, was to meet with German ambassador Ulrich von Hassell. Lonsdale-Bryans proposed a deal whereby Germany would be given a free hand in Europe, while the British Empire would control the rest of the world. It is unclear to what extent this proposal enjoyed the official backing of the British Foreign Office. Halifax himself had met with Hitler in 1937.[3][4]

Invasion of the Soviet Union

Template:Associated main Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941. Hitler believed that the Soviet Union could be defeated in a fast-paced and relentless assault that capitalized on the Soviet Union's ill-prepared state, and hoped that success there would bring Britain to the negotiation table, ending the war altogether.

One theory states that if Germany had not attacked, Stalin would have done so within the next couple of months, unleashing the Red Army and all the force the Soviet Union could bear. This would have been a disaster for the Germans, as the Wehrmacht would lose the element of surprise and the ability to maneuver, which contributed to the military's ability to confront the Soviets so successfully early on. Furthermore, the terrain of Germany's east would not have been favorable for defensive warfare because it is flat and relatively open. Still, the view promoted by Viktor Suvorov relies on numerous assumptions, including the underlying notion that a war between the two powers was, for various reasons, inevitable. However due to Russia's disastrous first few months of their war it is highly unlikely that any plans for the invasion of Germany had been put into any operation.

Suvorov's view that a Soviet invasion of Germany was imminent in 1941 is opposed by many historians like David Glantz, Gabriel Gorodetsky, Makhmut Gareev and Dmitri Volkogonov. But the Soviet assault thesis has gained some support among Russian professional historians like V.D.Danilov, V.A.Nevezhin, B.V. Sokolov and Mikhail Meltyukhov.

Attack on Pearl Harbor

Template:Associated main The Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, hoping to destroy the United States Pacific Fleet at anchor. Even though the Japanese knew that the U.S. had the potential to build more ships, they hoped that they would feed reinforcements in piecemeal and thus the Japanese Navy would be able to defeat them in detail. This nearly happened during the Battle of Wake Island shortly after.

Within days, Germany declared war on the United States, effectively ending isolationist sentiment in the U.S. which had so far prevented it from entering the war.

References

- ^ Chamberlain's radio broadcast, 27 September 1938

- ^ Zygmunt J. Gasiorowski: Did Pilsudski Attempt to Initiate a Preventive War in 1933?, The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 27, No. 2 (Jun., 1955), pp. 135-151 [1]

- ^ Lord Halifax tried to negotiate peace with the Nazis, the Telegraph, Sept. 4, 2008

- ^ UK diplomat sought deal with Nazis, Jerusalem Post, Sept. 2, 2008

- Carley, Michael Jabara 1939 : the Alliance that never was and the coming of World War II, Chicago : I.R. Dee, 1999 ISBN 1-56663-252-8.

- Dallek, Robert. Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932-1945 (1995).

- Dutton, David Neville Chamberlain, London : Arnold ; New York : Oxford University Press, 2001 ISBN 0-340-70627-9.

- Feis, Herbert. The Road to Pearl Harbor: The coming of the war between the United States and Japan. classic history by senior American official.

- Goldstein, Erik & Lukes, Igor (editors) The Munich crisis, 1938: Prelude to World War II, London ; Portland, OR : Frank Cass, 1999 ISBN 0-7146-8056-7.

- Hildebrand, Klaus The Foreign Policy of the Third Reich, translated by Anthony Fothergill, London, Batsford 1973.

- Hillgruber, Andreas Germany and the Two World Wars, translated by William C. Kirby, Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press, 1981 ISBN 0-674-35321-8.

- Seki, Eiji. (2006). Mrs. Ferguson's Tea-Set, Japan and the Second World War: The Global Consequences Following Germany's Sinking of the SS Automedon in 1940. London: Global Oriental. 10-ISBN 1-905-24628-5; 13- ISBN 978-1-905-24628-1 (cloth) [reprinted by University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 2007 -- previously announced as Sinking of the SS Automedon and the Role of the Japanese Navy: A New Interpretation.]

- Overy, Richard & Mason, Timothy "Debate: Germany, “Domestic Crisis” and War in 1939" pages 200-240 from Past and Present, Number 122, February 1989.

- Strang, G. Bruce On The Fiery March : Mussolini Prepares For War, Westport, Conn. : Praeger Publishers, 2003 ISBN 0-275-97937-7.

- Thorne, Christopher G. The Issue of War: States, Societies, and the Coming of the Far Eastern Conflict of 1941-1945 (1985) sophisticated analysis of each major power.

- Tohmatsu, Haruo and H. P. Willmott. A Gathering Darkness: The Coming of War to the Far East and the Pacific (2004), short overview.

- Wandycz, Piotr Stefan The Twilight of French Eastern Alliances, 1926-1936 : French-Czechoslovak-Polish relations from Locarno to the remilitarization of the Rhineland, Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1988 ISBN 0-691-05528-9.

- Watt, Donald Cameron How war came : the immediate origins of the Second World War, 1938-1939, New York : Pantheon, 1989 ISBN 0-394-57916-X.

- Weinberg, Gerhard The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany : Diplomatic Revolution in Europe, 1933-36, Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 1970 ISBN 0-226-88509-7.

- Weinberg, Gerhard The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany: Starting World War II, 1937-1939, Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 1980 ISBN 0-226-88511-9.

- Turner, Henry Ashby German big business and the rise of Hitler, New York : Oxford University Press, 1985 ISBN 0-19-503492-9.

- Wheeler-Bennett, John Munich : Prologue to Tragedy, New York : Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1948.

- Yomiuri Shimbun, The (2007). Who Was Responsible? From Marco Polo Bridge to Pearl Harbor. The Yomiuri Shimbun. ISBN 4643060123.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)- Review of this book: [3]

- Young, Robert France and the Origins of the Second World War, New York : St. Martin's Press, 1996 ISBN 0-312-16185-9.

External links

- The History Channel

- France, Germany and the Struggle for the War-making Natural Resources of the Rhineland Explains the long term conflict between Germany and France over the centuries, which was a contributing factor to the World Wars.

- The New Year 1939/40, by Joseph Goebbels

- "We shall fight on the beaches" speech, by Winston Churchill

- Czechoslovakia primary sources

- More Czechoslovakia primary sources