Austrian cinema history

The Austrian cinema history traces the development of cinema in Austria from the first screenings in the 19th century to the present day after.

Silent movie era

The first film screenings

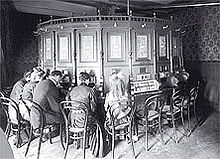

From 1885, the Kaiserpanorama , in which up to 12 visitors were allowed to view a stereoscope at the same time for a fee, was an early predecessor of the cinema .

1896 was the year when the first presentation of "Living Pictures" is said to have taken place in Josefine Kirbes' showroom in Wiener Wurstelprater . A little later, on March 20 of this year, the first documented public cinema screening with the Lumière cinematograph in front of an invited audience took place in the Vienna Teaching and Research Institute for Photography and Reproduction .

From March 27th there was a daily performance in the mezzanine of the house at Kärntner Straße 45 / corner Krugerstraße 2 in the First District of Vienna . There Eugène Dupont , an envoy from the Lumières who wanted to make their invention known in all major European cities, presented their first works. This was done for an entry fee of 50 cruisers and was possible daily from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. The program included short documentary scenes by Lumières that only lasted a few minutes. The Neue Freie Presse praised the quality of the recordings and delivered the first film review in Austria with its report on the opening of this screening room . In April 1896 the program was largely updated with newer works, and on April 17 the emperor also visited the establishment, who spoke to the owner in French - according to the Neue Freie Presse at the time.

The cinematographs, which were imported without exception - no such producer existed in Austria for years - can from then on mostly to be found with showmen in the Wurstelprater, at fairs , in traveling cinemas and also in Louis Veltée's “Stadt-Panoptikum” at Kohlmarkt 5. Johann Bläser is considered Upper Austria's first touring cinema operator . On November 29, 1896, Charles Crassé showed the first demonstration of living photographs in Klagenfurt .

It is also the traveling cinemas that are presenting the cinematograph for the first time in almost all of the major cities of the entire monarchy - unless the Lumière brothers personally came in first. The legal framework was the "Vagabonds and Showmen Act", enacted as early as 1836, which was also used for the acquisition of cinemas and the showing of films until the first half of the 20th century.

At that time one couldn't speak of real films. For technical reasons, only a few minutes long documentary and fictional “short films” with titles such as “Felling a Tree” , “Feeding the Pigeons” , “Shooting a Spy in the Turkish-Greek War” or “An Eerie Dream” were produced immediately in the show booths in the Prater or elsewhere in the city, among other abnormalities and curiosities. Who the actors were inevitably only played a subordinate role. The first “movie stars” with recognition value did not emerge until more complex and longer productions in the mid-1910s.

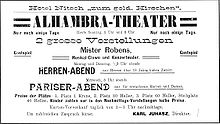

Also in 1897, short films were presented for the first time in Linz as part of a variety program in “Roithner's Varieté” . The first complete film screening took place on March 20, 1897 - in the garden salon of the hotel "Zum golden Schiff" . In the same year in Höritz in the Bohemian Forest , the first performance of locally produced film material took place during the performance of the play The Life and Death of Jesus Christ . A cinematograph was available to support the play - 3000 meters of film were shot in the area, of which 30 reels of 30 meters each were shown.

In December 1898, Gottfried Findeis's traveling cinema was a guest at the Wiener Neustadt hotel “Zum golden Hirschen” to present films in the style of the Lumière brothers: “The arrival of a train at the Wiener Neustadt station” , “A tunnel journey in the observation car taken during the journey ” and “ Exit of the workers from the Wiener Neustadt locomotive factory ” . Also in 1898 it was legislated that all entrepreneurs had to take an examination for the public showing of films. Nevertheless, the number of show booths and small theaters continued to grow in the following years. "Running Pictures" enjoyed great popularity.

Establishment of the first permanent cinemas

Until 1902, film screenings were only held in simple rooms in adapted restaurants or narrow, elongated business premises - so-called shop cinemas . In addition, in the courtyards of residential complexes, in the context of "abnormality shows" (for example the Homes Fey cinema ) and in circus tents. These rooms were furnished with the largest possible number of chairs, and the cinema program was accompanied by the serving of drinks and the sale of food. This was in contrast to the other European cities, which built their own cinema buildings from the start. The first building built specifically for the purpose of cinema was built in 1902, when the Viennese Singspielhalle operator Gustav Münstedt received the license to build a cinema. The " Münstedt Kino Palast " now replaced its Singspielhalle in the Vienna Prater. Between 1903, when there were only three venues in Vienna that exclusively showed film screenings, and in 1905, some of the show booths, theaters and tented cinemas developed into other exclusive cinemas. The centers were the inner city , the Wurstelprater and the Mariahilfer Strasse in Vienna- Mariahilf . One of them was the large "Westend tent cinema" built by Louis Geni in 1904 , the lighting system of which made the cinema well known.

In November 1907, the Association of Austrian Cinema Owners was founded in Vienna . In 1908 there were already six cinemas in the Prater, the Stiller , Schaaf , Münstedt , Kern , Klein and Busch cinemas, in which walk-in customers were recruited for the “cinematographic presentations” with the help of “criminals”. The criminals - also known as “re-commanders” - were often the cinema operators themselves who, as literal “figureheads” of early Viennese cinemas, drew the attention of walk-in customers to their operations. In doing so, they followed on from a tradition that had already existed in variety shows . They were replaced by display boards before the First World War.

As a model for the cinema operation they took the theater, and then about the writer and composer showed Max Brod with a visit to the cinema "amused that there is a spot, a cloakroom attendant, music, programs, ushers, rows of seats, all this pedantic as well like in a real theater with lively actors ” . Some of the 12 permanent cinemas that existed in Vienna around 1906 actually emerged from theaters. For example the Jantsch Theater , built in 1898 , which was renamed "Lustspieltheater" in 1905, and presented films in front of 800 to 1000 spectators. At that time, the silent films were mostly accompanied by electric organs on which the most famous opera and operetta melodies were played. In the early silent film era, however, there were also piano players called "tappeurs". So-called “explainer” ensured that the film content was correctly transmitted to the audience when necessary. As the length of the films increased, they quickly became indispensable until they were replaced by the subtitles built into the film .

In 1908 there were already 25 cinemas in Vienna - mostly shop cinemas like the “ Bellaria Kino ”. In the same year Sophie Nehez became the first woman to pass the Vienna film projectionist examination. The leading Viennese cinemascope cinemas in the first few years were the “Weltspiegel” and the “Eos Kino”. In 1908, Carl M. Köstner and Hermann Prechtl founded permanent "cinematograph theaters" in Klagenfurt . At that time there were already two cinemas in Villach . The first film magazines have already appeared: the “Kinematographische Rundschau” from 1907 and “Der Österreichische Komet” from 1908.

Further development of the cinemas until 1914

| Cinemas in Vienna | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | number | ||||||

| 1896 | 1 | ||||||

| 1903 | 3 | ||||||

| 1905 | at least 6 | ||||||

| 1906 | 12 | ||||||

| 1908 | at least 25 | ||||||

| 1909 | 74 | ||||||

| 1914 | 150 | ||||||

After the first few years of the “cinema boom”, the numerous films with the Frenchman Max Linder were extremely popular in the 74 cinemas in Vienna - 41 of which were within the belt . In this regard, the “ Kino Klein ” was able to gain a good reputation, as it was able to regularly come up with current foreign productions that it imported from Paris at an early stage. Max Linder released a new film every week in October 1910 alone: “Les Débuts de Max au cinéma” (Austrian premiere on October 1, 1910), “Comment Max fait le tour du monde” (October 8), “Qui a tué Max? ”(October 15),“ Max prend un bain ”(October 22) and“ Le Soulier trop petit ”(October 29).

In the numerous traveling cinemas of that time, mainly comedies and documentaries such as the Phantom Ride “Austrian Alpine Railway, a journey to Mariazell” were shown.

Since the “Vagabond and Showman Act” of 1836 still applied, there was a brisk, but unregulated, cinema movement in Vienna. Licenses were issued “as needed” to a cinema in a city district. This led to the fact that the mostly small shop cinemas often settled in less frequented side streets or alleys. The result was that many of these cinemas closed in the first few months and years, or moved to other, better-frequented streets while retaining their names.

The vague legal situation also resulted in questionable regulations and procedures in administration. In addition to emergency lighting , a “courtesy lamp” was mandatory for every cinema , and the Prater Inspection Authority closely followed the development of earnings during the cinema boom. In 1912, at the height of the boom, the rent for cinema operators was increased tenfold, while the other Prater businesses were spared this step of the chief stewardship.

In 1911 the "Association of Cinema Industrialists" was founded and in 1912 Vienna's first own cinema law, the "Cinematographs Ordinance", appeared. Since then, a license has been required to operate a cinema . In the same year, the International Cinematographers' Congress and the International Cinema Exhibition took place in Vienna , where filmmakers campaigned for film to be recognized as an art form, and the censorship and other harassment that made it difficult for filmmakers to do their work were severely criticized.

In 1913 there were around 400 cinemas in the entire monarchy, according to statistics from this year. About half of these were traveling cinemas, and of the 200 permanent cinemas, more than half were in Vienna.

On May 20, 1912, the first film screening in a school took place in the Bürgererschule on Friedrichsplatz in Vienna's 15th district of Rudolfsheim-Fünfhaus . In the same year the association "Kastalia" founded the "Erste Österreichische Schule- und Reformkinogesellschaft mbh", which then opened the first large school cinema "Universum" on Kriemhildplatz in Rudolfsheim-Fünfhaus. This was done according to the same pattern as in the case of the student presentations at the Urania , which was led by Schulrat Jaksch, to which school groups from all over Vienna were led.

From 1911 to 1914 102 new cinemas opened in Vienna, so that there were now no fewer than 150 cinemas. The permanent cinemas dominated the entertainment scene in the big cities. There were also several open-air cinemas and rooftop studios in Vienna. 25 production companies took care of diverse productions. At this time, the discussions about the “protection of children from film”, censorship in general, the relationship between theater and film operators and the like reached their climax, which is discussed in more detail in the section “Kulturkampf über Kino und Film”.

Dealing with state restrictions and resistance from the upper class

Certain sections of the population and the authorities saw cinema and film in the years of their creation, despite their great popularity, or precisely because of that, as “unculture”. The recognition of film as an artistic medium, which has not yet been fully recognized by official bodies, was already rooted in the "Vagabonds and Showmen Act" of 1836, which up until the 1920s equated cinema owners with vagabonds . This meant that cinema operators had to ask for a license and only received it at the discretion of the duty officer - or not.

A law banned children from going to the cinema from 1910, and complicated censorship exams continued to make life difficult for the film industry. Protests by cinema and filmmakers from 1907 onwards, who joined together in associations from 1910, did not lead to relief until 1912, at the “International Cinematographers Congress” in Vienna. The Vice-President of the “Federation of Cinema Industries”, Alexander Ortony, pointed out in a speech on this occasion that “many civilized peoples are completely without censorship, and nobody can claim that France, Italy or Hungary are therefore on the verge of ruin”. Similar to Austria, in Western Europe at that time only Germany was affected, which had a confusing and decentralized censorship system.

In the newspapers, film and literary magazines, articles from greats from film, theater and literature were constantly appearing, who engaged in a constant exchange of blows with pros and cons, such as whether the theaters are now being damaged and book sales are falling, or whether films are theirs Take, replace or supplement positions.

Although the first scientific treatises on cinema and film were published in 1913 ( Thoughts on the Aesthetics of Cinema by Georg Lukács) and 1914 in Germany ( On the Sociology of Cinema by Emilie Altenloh), this initially did nothing to change the increasing resistance from school authorities, the church, Police and theater associations against the cinema. This “culture war” only relaxed in the mid-1920s with the appearance of the great film-theoretical writings by Sergej Eisenstein and Béla Balázs .

In the first World War

As early as September 1914, Austrian cinemas received the first war weekly reports from the Austro-Hungarian Eastern Front (see also: History of the weekly newsreel in Austria ) . In 1916, the building authorities' requirements for the establishment of cinemas in Vienna were tightened considerably. Like the First World War, these conditions led to a series of closings and an initial stagnation in the number of cinemas being set up in Vienna. Nevertheless, more cinemas were opened in Vienna during the war. At that time, almost 50% of the cinemas in Vienna and around 90% of the rental companies were run by Jewish owners. In 1917 only four new cinemas opened in the city. After the end of the First World War, the former "Reich Association of Cinematographers" became the "Bund". In 1920 it was renamed the “Central Association of Austrian Film Theaters”. In 1918 only one cinema was added to the 154 existing cinemas in Vienna.

Development of the cinema up to the switch to the sound film

Since the introduction of the Cinematographs Ordinance in 1912, the terms and conditions for awarding cinema licenses have changed insofar as licenses to run cinemas and light shows were granted to non-profit organizations rather than individuals in the post-war years. As a result of the First World War, these were mainly war veterans , invalids and widows' associations , as they emerged in large numbers in the years after 1918. People's education associations, which ran a number of Viennese cinemas , especially during the years of “ Red Vienna ” - best known is the “Kosmos Kino” in Vienna's Neubau - were given preferential licenses. In 1919 five cinema licenses were awarded in Vienna, 13 in 1920 and 7 more cinemas in 1921.

In 1922 Ottakring was Vienna's most cinematic district with 13 movie theaters and 5,764 cinema seats. This was followed by highway , construction and Leopoldstadt (without Prater) with twelve cinemas. In the Prater itself there were eight cinemas with 4439 seats at that time, which meant the second highest number of seats in Vienna after Ottakring. In Favoriten , Meidling and in the inner city there were eleven cinemas each, in all other districts fewer than ten. The district with the fewest cinema seats was Döbling with almost 1,000. On December 31, 1922, the Filmbund was founded, an amalgamation of all interest groups for Austrian filmmakers.

It was not until eight years after the end of the war and the end of censorship in the course of the establishment of the republic that cinema censorship was abolished in 1926. Despite the introduction of a license requirement for imported foreign films - as a result of the poorer situation of Austrian production companies - the film distribution companies are flourishing more and more. In 1926 the “first Viennese cinema law” was enacted, according to which competence in cinema matters was from now on with the state. In that year, the Kiba cinema operating company was also founded by the City of Vienna. From then on, she dealt with the acquisition of cinemas in which she wanted to bring about an ideological and cultural improvement in film.

In 1927 Vienna had 178 cinemas with 67,000 seats and 308 standing places. Only four Viennese cinemas held more than 1000 people, the majority of the other Viennese cinemas held between 200 and 400 people. There were already 750 cinemas across Austria.

In the course of the global economic crisis of 1929, there was a unit price of 50 groschen per parquet seat in Vienna and 60 groschen per balcony or box seat. In the same year the first sound film was shown, which led to the first violent protests of the cinema musicians. As a result, most of Vienna's silent film cinemas were consistently converted into sound film cinemas.

Early sound film era up to the time of National Socialism

Development of cinema in the turbulent environment of the 1930s

The first cinemas to switch to sound film were in 1929 the cinemas “Ufa”, “Burg Kino” and “Opern Kino”. The Tobis sound film process was used. The share of sound films in the total number of films shown rose to 158 from 569 this year. One year later, talkies were already predominant in the cinemas, and in 1932 no more silent films were shown in Vienna. This caused a serious crisis for the so-called cinema musicians , who demonstrated several times on the streets of the capital from 1929 onwards.

The first full-length sound film reached Austria on January 21, 1929 - in Vienna's Central Cinema on Taborstrasse. It was Alan Croslands "The Jazz Singer" , which premiered in the USA on 23 October 1927 and in Austria under the title "The Jazz Singer" was running. The sound was played on a record in sync with the film.

Many of the former small Grätzel cinemas did not survive the introduction of the sound film for financial reasons, and other, better-off cinemas used this upheaval phase for major renovations such as the beautification of portals, entrance and ticket halls , auditoriums and technical facilities. To the three sound systems that included not only the most used were then used in the Viennese cinemas Movietonverfahren of Western Electric and the sound film system of that Tobis Klangfilm of Ufa and the Magnettonverfahren . The Selenophon process could only be temporarily spread internationally through an agreement with Tobis.

When the US film " Nothing New in the West " premiered in Vienna on January 3, 1931 , it led to a political scandal, accompanied by demonstrations, disruptions and riots by the National Socialist and Christian Socialist parties and their armed arm, the Heimwehr . The Austrian Minister of Defense, Carl Vaugoin , wanted to ban the novel on which the film is based . The federal government recommended that the federal states issue a performance ban. When rioting and tumult broke out again after the second performance in the "Schwedenkino" (Kiba), the Minister of the Interior banned any further performance on January 9th.

In 1931 the City of Vienna's cinema management agency, the “Kiba”, already had 30 cinemas with a capacity of 16,000 visitors. For the most part, the recordings of the "Federal Security Film Guard", which had been filming public events since 1928, were not intended for public screening and which today represent an essential addition to the other contemporary reports and documents. For example the recordings of the “International Communist Demonstration Day” in 1930, the “International 2nd Workers' Olympiad” in 1931 and the military-technical preparation for the civil war in 1932.

In the Austrian corporate state , the "Central Association of Austrian Film Theaters" was converted into a public corporation in 1933, and the representation of interests was reorganized. A committee of film companies in Austria was set up, which functioned as a corporation under public law and to which every cinema operator in Austria had to belong. The structure of the body remained essentially identical to that of the central association from 1920.

In 1934, several federal states reintroduced film censorship in the Austrian corporate state . In 1935, the new "Wino Cinema Act" was followed by a further tightening of the corporate control measures. At that time there were 179 cinemas in Vienna and 738 throughout Austria.

From 1937, due to an amendment to the Vienna Cinema Act, a license could only be granted to those who could prove an actual need (“local need”) for a new cinema location. In 1937 there were only 23 silent film cinemas left in Austria - exclusively in Vienna and Vorarlberg . There were also 839 sound film cinemas, of which 320 were in Lower Austria , 189 in Vienna and 95 in Styria . Vienna had 26.44 million cinema-goers in 1937.

Austrian cinema scene at the time of National Socialism

Immediately after the invasion, on March 12, 1938, the "Central Association of Austrian Film Theaters" as well as the "Committee of Austrian Film Entrepreneurs" and all other film organizations were dissolved and taken over into the Reichsfilmkammer . An essential requirement for admission was proof of parentage , which was supposed to ensure compliance with the Nuremberg Race Laws .

All cinemas whose owners were considered Jewish according to the Nuremberg Race Laws were “ Aryanized ” after the annexation of Austria . 84 of Vienna's 170 cinemas - around half - were affected. A list published in the “Kinojournal” in August 1938 reported that shortly after the Anschluss there were 65 “Jewish”, 19 “Jewish” and 86 “Aryan” cinemas in Vienna. By October 1938, 55 of the Vienna cinemas had been handed over to "deserving party comrades". The largest cinemas in the city, such as the “Scala”, “ Apollo Kino ” and the “Zentral Kino” went to “Ostmärkische Filmtheater Betriebs Ges.mbH”, a subsidiary of the German “Filmtheater GmbH”. This means that the "synchronization" has also taken place here. The urban Viennese Kiba was the only non-nationalized chain of operations that was allowed to continue to exist in the “ Danube and Alpine Gauz ” alongside the “Aryanized” individual businesses.

In December of that year, the "Aryanization" was completed except for the "Westend" and the "Arkaden Kino". The cinemas “Kruger”, “Nestroy”, “Votivpark”, “Sweden” and “Elite Kino” as well as the “Burg Kino” were the only Viennese cinemas still to play “hostile films” from foreign languages.

In the years that followed, the term “cinema”, which sounded too “foreign”, was often replaced by “light plays” or “film theater”. The “Maria Theresien Kino” was renamed “Ostmark” by the newly appointed concessionaire, other former “cinemas” simply lost the “surname” that was used up until then and were simply called “crank”, “cross” or “royal” in the following years. Only the "Höchstädt Kino" was able to keep the nickname "Kino" until 1941. The "Central Cinema" was renamed " Ufa Cinema ".

In 1939 the number of cinemas in Vienna reached 222, a high that has never been seen before. From then on, the number of cinemas decreased significantly.

On January 8, 1943, the Vienna Police President introduced the closure of the cinema from 10 p.m.

Heavy bombing raids in June 1944 destroyed around a quarter of all Vienna cinemas, including the “Busch Kino” in the Prater , the “Sascha Filmpalast” and the “Schweden Kino”. On September 1st, all theaters were banned from playing, but cinemas were allowed to continue playing. The destruction of some cinemas by bombing led to the curiosity that from October 6, 1944, the Volksoper became the second largest cinema in the city with 1,550 seats for a few months. Open-air demonstrations were also planned for the summer months. However, nothing in this direction has been achieved.

Shortly before the end of the war, in April 1945, more cinemas in Vienna were destroyed in air raids, and the history of the lively cinema scene in Vienna's Prater also ended when it was destroyed in the bombing at the end of the Second World War . Only the comedy theater continued to exist under different names until a fire in 1981.

Development of cinema in the Second Republic

In the post-war years

| Cinema visits in millions |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | Austria | Vienna | |||||

| 1956 | 116.1 | 47.5 | |||||

| 1957 | 119.9 | 47.1 | |||||

| 1958 | 122.0 | 46.3 | |||||

| 1959 | 114.9 | 42.9 | |||||

| 1960 | 106.5 | 37.9 | |||||

| 1961 | 100.5 | 33.9 | |||||

| 1963 | 84.7 | / | |||||

| 1968 | 46.4 | / | |||||

After the occupation of Austria by the Allies, the Austrian cinemas had to remain closed for a month until the Allied surveillance body, the “ Information Service Branch ”, was installed. He took over the program supervision as well as the “ denazification ” of the artists working in film and theater. On May 10th of that year, the relevant law on "denazification" was passed - all "Aryanizations" of cinemas were declared invalid.

In the implementation of the denazification measures, however, numerous irregularities occurred in Vienna. 30 of the "Aryanized" cinemas did not go to their former owners or their heirs, but to the city's own Kiba , as the City of Vienna only wanted to return cinema concessions to the previous owners or their direct descendants and did not accept any other heirs or legal successors.

Also in May, the former “Reichsfilmkammer” was reestablished under the new administration as the “Committee of Austrian Film Companies” (“Central Association of Austrian Film Theaters”). A bomb fund to repair the worst damage has also been set up. By August 1945, 35 cinemas were back in operation.

In 1953 there were still over 200 cinemas in Vienna - numerous district and Grätzel cinemas, which in the first few years after the end of the war benefited from the numerous international films that could finally be shown in Vienna. On October 1, 1954, 32 cinemas in Greater Vienna were transferred to Lower Austrian territory as a result of a new border being drawn .

In 1955 the Vienna Cinema Act was enacted, which was amended several times in the following years - most recently in 1980. It stipulates that cinema operations must be licensed . Every operation must take place in an approved operating facility and employ a trained and certified projectionist who must be reported to MA 7 . In the same year, the Cinema Operational Establishment Ordinance was also published, most of which were based on the first provisions of the cinema building law from 1916.

The head of the umbrella association of movie theaters, Otto Hermann, responded to the dwindling number of visitors in the cinemas on behalf of his members with the battle cry: "Television - not with our films" . However, television came to its movies and the decline in visitors continued. From then on, the number of in-house productions steadily decreased in favor of commissioned productions . When Austrian film producers gave their world rights to German distributors, it often happened with resale that business partners forgot to name Austria as the country of origin.

From the 1970s until today

| Cinema visits in millions |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | Visits | ||||||

| 1973 | 23.89 | ||||||

| 1978 | 17.43 | ||||||

| 1983 | 17.89 | ||||||

| 1988 | 10.02 | ||||||

| 1990 | 10.15 | ||||||

| 1995 | 11.99 | ||||||

| 2000 | 16.30 | ||||||

| 2004 | 19.38 | ||||||

| 2005 | 15.68 | ||||||

| 2006 | 17.34 | ||||||

| 2007 | 15.69 | ||||||

| 2008 | 15.63 | ||||||

The 1970s began for Austrian cinemas with a massive decline in attendance, accompanied by the closure of hundreds of cinemas. While in 1962 90.75 million people and in 1969 39.5 million people visited the Austrian cinemas, the number fell to 20.8 million by 1975. By 1982 the number continued to fall to 18.3 million, while the number of television connections passed the two million mark. Between 1960 and 1977, a total of 700 cinemas closed their doors between the onset of “cinema dying”. The decline was particularly drastic from 1965, and then between 1970 and 1972, which are considered the blackest years in Austrian cinema history. During these three years, a third of all domestic cinemas closed.

The main reasons given are the increasing spread of television sets and more diverse leisure opportunities. The numerous closed small cinemas in small towns and rural communities were later replaced by cinema centers . The first opened in Braunau in 1979 , and Vienna followed in 1980 with the “Multiplex”. The relocation of the still existing cinema capacity from rural communities and inner cities to the cinema centers on the outskirts and in the suburbs began.

During these years, owners of larger cinemas also joined the international trend of dividing large halls into several smaller halls. In this way, the poor occupancy of the large halls could be countered and more films could be shown at the same time. In the 1970s, due to a young, critical audience, the first alternative cinemas appeared, in which films were shown that would otherwise not have been shown in Austria. In 1983 there were 96 halls in 69 cinemas in Vienna. In 1984 the “Vienna Cinema Exhibition” took place in Vienna's Stadthalle . In 1986 there were 536 cinemas in Austria, 97 of them in Vienna.

Since the first public cinema screening in 1896, around 400 cinemas have been occupied in Vienna. While there were cinemas in all districts at times, in 1992 there were already nine districts in which there were no longer any cinemas. In the other districts there were five with only one cinema. However, a number of the cinemas were sex cinemas .

In 1993 there were 260 cinemas in Austria, 50 of them in Vienna. In 1994 there were only 379 cinemas, the number rose to a new high of 564 by 2001. In Vienna alone, the construction of several large cinema centers resulted in such a high surplus of seats and the associated low occupancy that the number of cinema halls fell from 191 to 166 between 2001 and 2002 alone due to economic problems. Across Austria, the number of cinemas continued to fall, to 176 in 2003. The number of auditoriums also fell slightly again, to 553. These had a capacity of around 100,000 seats. This year there was an average of three halls with around 181 seats for each cinema. The Erika Cinema in Vienna, which was founded in 1900, was considered the oldest cinema in the world until it closed in 1999.

A cinema that has been used continuously since 1920 is a country cinema in Drosendorf . The cinema was operated by the owner of the Gasthof Failler in the center of the small town until 1990. Since this year, the Drosendorf Film Club , which also operates a traveling cinema in Lower Austria , has been using the original projection equipment at more or less regular intervals.

literature

- Walter Fritz : I experience the world in the cinema: 100 years of cinema and film in Austria. Brandstätter, Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-85447-661-2 .

- Ludwig Varga: The Philadelphiakino. Sheets of the Meidlinger Bezirksmuseum, Vienna 2002, issue 55.

- Doris Schrenk: Cinema in Vienna, from its beginnings to the present (PDF; 1.0 MB) , diploma thesis, 2009

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Richard Kutschera: Beloved dream world . Linz 1961

- ^ Peter A. Schauer: Films in old Austria. The Höritzer passion film. Vienna 1996

- ^ E. Kieninger: A la Lumière . In: Medien und Zeit 4 (1993), p. 23

- ↑ Kinematographische Rundschau , November 15, 1907. In: Francesco Bono, Paolo Caneppele, Günter Krenn (Eds.): Elektro Schatten , Verlag Filmarchiv Austria, Vienna 1999, p. 14

- ↑ Kinojournal, August 27, 1938

- ↑ On the situation of Austrian cinema (PDF) ( Memento from January 14, 2005 in the Internet Archive ), Andreas Ungerböck, Austrian Film Institute , no date

- ^ Georg Tillner: Austria, a long way. Film culture between Austrofascism and reconstruction. In: Ruth Beckermann, Christa Blüminger: Without subtitles. Fragments of a History of Austrian Cinema. Sonderzahl Verlag, Vienna 1996, p. 180

- ↑ Austrian film and cinema newspaper. No. 495, January 21, 1956, p. 1

- ↑ Association of movie theaters and audiovisual organizers: page no longer available , search in web archives: wko.at - visitor numbers according to AKM 2001–2009 (PDF) , (accessed on November 8, 2009)

- ↑ Mella Waldstein & Willi Erasmus: Kino Drosendorf, stories of a country cinema , ISBN 3-85252-511-X