History of the Austrian silent film

The history of the Austrian silent film is unusual in many ways. After the presentation of the first cinématographeen in Vienna by the Lumière brothers in 1896 (see also: Austrian cinema history ) , it took around 10 years for Austrians to venture into the commercial production of films for the first time . It was not until 1910 that continuous film production began , and during the First World War , the establishment of an independent film industry was made up for.

The main drivers of this development were the first two and largest Austrian film production companies , the Viennese art film industry and the Sascha film industry . After the end of the war, Austrian film production continued to grow and numerous film companies were founded. Annual film output rose from barely a dozen at the start of the war to around 100 in 1918 and between 1919 and 1923 was 130 to 140 films a year. Like Germany, the Austrian film industry benefited from the sluggish film production in the rest of Europe after the end of the war and from the high inflation in its own country. This made domestic film productions comparatively cheap for foreign buyers, while the quality could keep up with the international level.

This boom subsides in 1923 down again, as the highly efficient operation of a film industry in Hollywood in the 1920s, is the world market under great pressure and falling inflation Austrian film productions abroad also still expensive. Only a few major film producers survived this crisis.

In the comparatively short but all the more intense Austrian silent film era , in addition to sales-oriented mass-produced products such as monumental films , contributions to expressionist films were made and numerous film talents, who later achieved international fame, were discovered and promoted by Austrian film producers.

Background: Contributions to the development of film technology

The history of film art in Austria begins decades before the first film showing with the invention of the “ wheel of life ” (“magic disks”) by the Tyrolean mathematician and astronomer Simon Stampfer . Some years later, Franz von Uchatius by tests that "magic wheels" with the magic lantern to combine, making moving images more than one person can be presented simultaneously. The result was the “apparatus for displaying moving images” , which was presented for the first time by the showman and magician Ludwig Döbler on January 14, 1847 in the Josefstädter Theater . Prerequisite for this was the first bright portrait lens, that of Josef Maximilian Petzval calculated 1840 Petzval lens , which the Viennese optician and mechanic Peter Wilhelm Friedrich von Voigtländer was ground.

On January 25, 1891, Viktor von Reitzner registered a “photographic, continuously working serial and projection apparatus” for a “privilege” (= patent ), and in March a patent was issued in Germany. However, it was not evaluated until 1896 under the name " Kinetograf ". Theodor Reich, in turn, designed sketches for a cinematographer as early as 1887 , but did not patent them. In 1895, before the Lumière brothers presented their cinematograph, Theodor Reich also designed a cinematograph while attempting to produce a chronophotograph . However, the evaluation of the device failed after several years because it was too susceptible to fire. In 1904 August Musger finally invented a device for producing and projecting slow-motion recordings, but failed to construct it due to a lack of money and technical equipment. When he could no longer afford to extend his patent, the German company Ernemann brought out a device based on his plans in 1914 .

As early as 1897, Hermann Casler experimented with the 70 mm film process, which was not introduced into cinema practice until the middle of the 20th century.

In 1898 Paul Rudolph developed a new method for image enlargement with the Cinemascope process . However, the Cinemascope film did not become a major competitor to previous film productions until the 1950s.

Early silent film era, until 1914

First domestic film productions

The first film companies in Austria came from France. Pathé Frères was the first to open a branch in Vienna in 1904 and began both with the production of documentary film recordings for newsreels on site and with the distribution of its own short film productions made in France. Several cinemas were also built to strengthen sales. Gaumont followed her in 1908 and the Société Eclair in 1909 . They caused great competition in the newsreel sector for regular Austrian film production, which began in 1910, until the outbreak of World War I. The first Austrian film company was a pure film distribution company, which was founded in 1905.

With Joseph Delmont , for example , who began his career as a director and screenwriter in the United States in 1903, and who created film sensations around the world with “wild predators” in his films, there were early Austrian filmmakers - but Austrian film productions were not made until later. The first non-private Austrian film recordings are said to have been shown publicly as early as 1906 - by Josef Halbritter , who founded Halbritter-Film a few years later . In contrast, the erotic short films by the Viennese photographer Johann Schwarzer are documented . These are the oldest known domestic film productions and originated from the middle of 1906. To market his productions, he founded Saturn-Film , under whose name he created catalogs for the selection of films , which he also sent abroad. The films quickly enjoyed great popularity in the international men's world, as did the French erotic films, which had been made for several years. Schwarzer's short films had significant titles such as “A Modern Marriage” (1906), “Am Sklavenmarkt” , “The Sand Bath” and “Female Wrestlers” . His business activities came to an end in 1911 when the police confiscated the films. Some of the short films are still preserved today and are in the Austrian Film Archive .

The first full-length Austrian feature film with a length of 35 minutes, “From Step to Step”, is said to be directed by Heinz Hanus - who is also said to have written the screenplay with Luise Kolm - the producer and husband of Luise, Anton Kolm , and assistant Jacob Julius Fleck was premiered in Vienna in December 1908. But the only one who was able to testify to this in research that was only carried out decades later was the alleged screenwriter and director Heinz Hanus himself. However, he did not spare the details of the film and the actors. In the newspaper reports or in the two film magazines of the time, however, there was no reference to a showing of this film, contrary to what was customary at the time. There is also no other evidence such as scripts. Several films with the title “From Step to Step” could be tracked down, but these came from the German, French and American producers Pathé (1907), Duskes (1910), E. Grünspan (1912) and Universal (1913). All that is documented is a theatrical performance by Robert Stolz - "Das Glücksmädel" - in the Raimund Theater in Vienna in 1910, which was largely similar in content to what was supposedly the first Austrian feature film.

To upgrade the film recordings of the Viennese operetta “The Waltz Dream”, a total of 19 sound images were created between 1908 and 1910 ( shellac record was shown synchronously with the film), which helped the operetta to become popular across Europe. In 1909 the first precisely datable documentary film from Austrian production was released. Between September 8 and 11, 1909, Photobrom GmbH filmed “The Imperial Maneuvers in Moravia” in Groß Meseritsch , on which Emperor Franz-Joseph and his German colleague Kaiser Wilhelm II acted. However, this remained the only production of this company.

In 1910 the “ First Austrian Cinema Film Industry ” was founded by the couple Anton and Luise Kolm - the daughter of Louis Veltée - and Jakob Fleck . Their first production appeared in the spring of the year: The carnival procession in Ober-St. Vitus . A little later, on March 14th, the start-up filmed the funeral of Mayor Karl Lueger . The film was shown in 22 cinemas in Vienna. The Austrian comet commented on this in its March 24 issue with “So finally a Viennese film that will make its way through the world.” The first advertising production in the broader sense was also made as early as 1910: because women's hats were very popular at the time , but caused poor visibility in the back rows in cinemas, Anton Kolm produced The Hat in the cinema to remedy this problem. In the same year, the company was renamed “Oesterreichisch-Ungarische Kinoindustrie Ges.mbH”, and in 1911 it was re-established as “Wiener Kunstfilm-Industrie Ges.mbH”.

Wiener Kunstfilm under Anton Kolm reacted to the dominance of the Austrian film market by French and other foreign film companies by increasing the production of daily reports for the Viennese cinemas. In addition to fires and other accidents, there were also historically valuable recordings of events such as the launch of the kuk-Kriegsmarine battleship SMS Zrinyi in the port of Trieste or the flight week at the Wiener Neustadt airfield - the largest airport in the world at the time.

In the (short) feature film production, Anton Kolm introduced the comic short film based on the French model . With the Berlin actor Oscar Sabo he had found his leading actor for “The Evil Mother-in-Law” (1910). In 1911 Kolm filmed “Types and Scenes from Viennese Folk Life” , which featured the famous Viennese folk singer Edmund Guschelbauer , and in 1912 “ Karl Blasel as a dentist” with the main actor of the same name, who had been a popular Viennese comedian for around a decade.

Fight for the recognition of the film as an art form

Certain sections of the population and the authorities saw cinema and film in the years of their creation, despite their great popularity, or precisely because of that, as “unculture”. This negative aspect persisted in Austrian films for a long time, which is reflected, among other things, in the fact that, decades late, Austria was the last Western European country to pass a film funding law. Until the 1980s, Austrian film history was hardly discussed or viewed as a cultural component of Austrian history. The hesitant approaches of the Austrian universities to the scientific discussion of the Austrian film history were always only financially supported minimally.

The recognition of film as an artistic medium, which has not yet been fully recognized by official bodies, was already rooted in the "Vagabonds and Showmen Act" of 1836, which up until the 1920s equated cinema owners with vagabonds . This meant that movie theater operators had to ask for a license and only got it at the discretion of the duty officer - or not.

A law banned children from going to the cinema from 1910, and complicated censorship exams continued to make life difficult for the film industry. Protests by cinema and filmmakers from 1907 onwards, who joined together in associations from 1910, did not lead to relief until 1912, at the “International Cinematographers Congress” in Vienna. The Vice-President of the “Federation of Cinema Industries”, Alexander Ortony, pointed out in a speech on this occasion that “many civilized peoples are completely without censorship, and nobody can claim that France, Italy or Hungary are therefore on the verge of ruin”. Similar to Austria, in Western Europe at that time only Germany was affected, which had a confusing and decentralized censorship system. Until 1918 the actors of the Burgtheater were forbidden to appear in any form of film. Exceptions were very rare. Other theaters, such as the Volkstheater , followed this example in order to protect themselves from direct competitors, the cinema. It was only with the appearances of Alexander Girardi and the productions of the artistic director Max Reinhardt from 1913 that the situation began to ease somewhat.

In the newspapers, film and literary magazines, articles from greats from film, theater and literature were constantly appearing, who engaged in a constant exchange of blows with pros and cons, such as whether the theaters are now being damaged and book sales are falling, or whether films are theirs Take, replace or supplement positions.

Although the first scientific treatises on cinema and film were published in 1913 (“Thoughts on an Aesthetics of Cinema” by Georg Lukács) and in Germany (“On the Sociology of Cinema” by Emilie Altenloh) in 1914, this initially did nothing to change the increasing resistance of School authorities, church, police and theater associations against the cinema. This “culture war” only relaxed in the mid-1920s with the appearance of the great film-theoretical writings by Sergej Eisenstein and Béla Balázs .

Film scene around 1910

In 1911 the German-Austrian co-production “Der Müller und seine Kind”, part one, appeared in which, in addition to the German silent film stars Henny Porten and Friedrich Zelnik , an Austrian with Curt A. Stark also played, as well as the purely Austrian sequel with others Cast, The Miller and His Child, Part II , produced by the Viennese art film industry .

At that time people liked to fall back on literary models of well-known writers in order to lure audiences into the cinemas with well-known titles. Due to the lack of sound and the short recording time available, however, the storyline of the books could only be reproduced in a greatly weakened manner. In order to enhance the short films in other ways, however, films were already colored back then . This was done both manually and with chemical methods. Austria's only major film company at the time, the Viennese art film industry, relied on works by Ernst Raupach , Franz Grillparzer , ETA Hoffmann and Ludwig Anzengruber in their productions . However, such film adaptations were inspired by the Paris production company " Film d'Art ", which ordered its manuscripts from the most famous authors as early as 1908 in order to have them realized by the directors and actors of the largest French theaters.

In 1911, in addition to the aforementioned social drama “Der Müller und seine Kind” , “Der Dorftrottel” , “Die Glückspuppe” , “Mother - Tragedy of a Factory Girl” and “Just a Poor Servant” , all of them from the Viennese art film industry, were based on literature were manufactured.

The writer Felix Salten , who published a book about the Wurstelprater in 1911 , gave the film a great future, something that only few could see in the primitive short productions at the time. But he also only wanted to grant the film artistic aspirations "if directors and actors were able to stand out from the level of poor provincial theaters" .

Based on a popular novel by the French George du Maurier , the film "Trilby" was released in 1912 , which was filmed again in a somewhat longer form in 1914 under the name "Svengali" . In 1915 and 1932 the book was made into a film in the USA and in 1927 in Germany. In 1913 a French director shot the first Speckbacher film in Tyrol. Apart from a few film recordings by foreign and Viennese film production companies , no organized filmmaking could be discerned in the rest of today's Austria. The first film companies outside Vienna were not founded until 1919.

Using the possibilities of the cinema instead of rejecting it like some representatives of the upper classes, however, wanted the Viennese high school professor Dr. Alto Arche , when in 1907 he applied for a grant of 300 crowns for the production of educational films. This was granted to him, but the films that are still preserved today, showing, for example, glassblowers, a master potter and fabric dyer at work, but also gymnastics, did not appear in cinemas until 1912. The first film screening in a school took place on May 20, 1912 in the community school on Friedrichsplatz in the 15th Viennese district of Rudolfsheim-Fünfhaus .

In 1912 the librettist Felix Dörmann founded the “ Vindobona Film ” together with the architect Tropp , who left that same year . It was subsequently renamed “Helios Film”, in 1913 into “Austria Film” and then into “Duca Film”, whose recording studio was located at Kandlgasse 35 in the seventh district of Vienna, Neubau . Since Dörmann's productions did not bring the hoped-for success, he speculated with the visitors' need for nude scenes. Films such as “A Day in the Life of a Beautiful Woman” , “The Goddess of Love” and “Affair” appeared , which attracted attention because the leading women were often shown in the bathroom, changing socks and even visiting the toilet. The bathing scenes in particular were the reason for the police to censor these films, even years after Johann Schwarzer's “spicy films”. Felix Dörmanns Filmgesellschaft ended its activities in 1914, not least because of the lack of success.

1912 was the year in which the theater director and artistic director Max Reinhardt realized his first film project in Austria. With his specially founded film company, he directed the literary film adaptation " The Miracle " . In 1913 Reinhardt signed a contract with the Berliner Projektions-AG Union ( PAGU ) to produce several films for 600,000 marks in the following years. The result, however, was only two silent films produced in Italy: “The Island of the Blessed” and “A Venetian Night” . In “The Island of the Blessed” there were extensive nude and sex scenes, which is why large parts of the film should have fallen victim to film censorship. In fact, it was not cut as required by the censorship authority.

As the domestic and international film industry flourished, more film magazines gradually emerged. “Das Lichtbild-Theater” and “Dramagraph-Woche” followed from 1911, and from 1912 “Filmkunst” appeared, which was commissioned by the “Cinéma Eclair”. Also in 1912 was the "Kastalia", which was published for academic and educational films by school people. In the following years "Die Filmwoche" (from 1913) and "Paimanns Filmlisten" (from 1916) followed - a magazine in which up to 1965 reviews of all films released in Austria were listed in lexical form.

Procedure for filming

However, JH Groß was the second after director Walter Friedemann to describe his film work. In the Austrian Comet , issue No. 151 of April 5, 1913, he once wrote a report on his filmmaking under the title Die Wiener Kinokunst . Regarding the casting of actors in his films, he stated: “However, I am the greatest enemy of so-called facial expressions in the cinema, who disrupt ballet-like movements and appear unnatural. But I am just as much an enemy of what is being done in Germany now, for example letting a hairdresser be played by a real hairdresser and a waiter by a real waiter. The dilettante becomes unnatural and awkward the moment he comes on stage. Only actors and well-paid actors should be used [...] When casting the roles, I proceed according to the appearance of the actor, so that as little wigs and make-up as possible have to be used. "

About the difficulties during the shooting he wrote: “The apparatus must not be more than 5 1/2 m away from the actor, so that the front clearance is a maximum of 4 1/2 m. So the people who otherwise stand next to each other must be arranged one behind the other. The difficulty is that nobody is covered, that freedom of movement is preserved and that the whole thing looks natural. "

Experiments to make the film more attractive

It was also JH Groß who, together with a Mr. Brüll, had a patent issued for the combination of film and theater performances. Reality should work together with the movie. “For example: A ball from the film is thrown by a person at the viewer, caught by a real person here and then thrown back to the person in the audience. Order a bar girl to go out of the film into the audience, serve them with refreshments and return to their shadowy film life ” , so Groß also in his Die Wiener Kinokunst article. This concept was experimentally implemented under the direction of Hans Otto Löwenstein in 1913 in the Adria exhibition , which, similar to the Venice theme park in Vienna , featured replicas - in this case of Adriatic views, ship models and a small pond as the Adriatic. The film "King Menelaus in the cinema" was supplemented with actors on the stage in front of the screen, who included the audience.

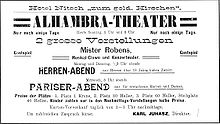

In order to achieve an apparent plasticity of the film images, the Viennese Karl Juhasz and Franz Haushofer founded the “Wiener Kinoplastikon Ges.mbH” in a theater on the Naschmarkt , which later became the “Wienzeile Kino” . The movie screen was on its own decorated stage. The Viennese art film industry produced several colored titles especially for this theater in 1913: "The Boxers" , "The Conscience" , "Helpers in Need" , "The Hungry Knight" and "Mirza, the White Slave" . However, since it was not successful, the theater did not last long and the idea was forgotten again.

While " sound images " have been produced abroad, in Germany primarily by Oskar Messter , attempts are said to have been made in Vienna as early as 1913 to produce sound films using the Kinetofon method. Unfortunately, details are not known.

Development of filmmaking until 1914

On March 15, 1912, the premiere of the first major film from Austrian production took place in Vienna: “The Unknown” - based on a crime drama by Oscar Bendiener . The director was Luise Kolm , who turned 10,000 meters of negative material and used 10,000 crowns for the production. The actors hired, among others, the Viennese crowd favorite Karl Blasel as well as Viktor Kutschera , Karl Ehmann , Anton Edthofer , Hans Homma and Eugenie Bernay . Claire Wallentin from the German Volkstheater played Countess Claire Wolff-Metternich-Wallentin in a costume from the Austrian Theater Costume and Decoration Atelier .

In November 1912, when other Austrian film production companies were already fighting for market share in the cinemas with foreign competition, “Das Gänsehäufel” was the first documentary of the Viennese art film industry , which, in addition to newsreels of current events, mainly concentrated on feature films. In the same year, Alexander Joseph "Sascha" Count Kolowrat-Krakowsky , who had just moved to Vienna, founded the " Sascha Film Factory " in what is now the district of Liesing in Vienna . His first production was "The extraction of ore on the Styrian Erzberg in Eisenerz" . This was followed by Austria's first historical feature film: " Emperor Joseph II. " . The “Vindobona-Film” production “ Die Musikantenlene ” was also released in 1912 , with the critically acclaimed leading actress Eugenie Bernay.

The most interesting new discovery of this year is the comedian Heinrich Eisenbach , who made his first appearances in the “ Budapest Orpheum ”, a cabaret located in the center of the Jewish immigrant quarter in Vienna- Leopoldstadt , and was nicknamed “Wamperl”. He performed well-known cabaret solo scenes in films such as “Hausball beim Blunzenwirt ” or “Klabriaspartie”, where the behavior of Jewish card players in the coffee house is shown. Other comedians also gained film notoriety at the time. In addition to the aforementioned Karl Blasel, there were “Pampulik” Max Pallenberg , “Cocl” ( Rudolf Walter ) and “Seff” ( Josef Holub ), who appeared together as Cocl & Seff from 1919 at the latest .

In “Die Zirkusgräfin” the “Vindobona Film” from 1912 he played the circus clown, alongside Eugenie Bernay as “Minka”. Felix Dörmann himself also appeared in this 900 meter long film as “Graf Veckenhüller”.

In September 1913, sound films were presented for the first time in Vienna with screenings under the title “Talking Film” in the Sofiensäle ( Edison Kinetophon and Gaumont screenings ). For various reasons - mainly because of the high material costs and the inadequate international rental at the time - these were not very well received. In 1913, a mass scene was used for the first time in an Austrian film - in “Injustice does not flourish” by Wiener Kunstfilm.

Although Emperor Franz Joseph was generally skeptical or even negative about technical innovations, he had a positive opinion of the film - probably in recognition of the great advertising and propaganda potential of this medium, which is particularly popular among the ordinary population. He was often filmed during his activities: for example at the "Imperial Maneuvers" with his German counterpart Kaiser Wilhelm in Moravia in 1909, at the chamois hunt in Bad Ischl in the same year , at the wedding of heir to the throne Karl in Schwarzau in 1911 , or at the Adria exhibition in Vienna in 1913. When the emperor died in 1916, the last major “court report” from the monarchy was written. Sascha Kolowrat-Krakowsky filmed the funeral for cinemas in Vienna.

In 1914 Max Neufeld , who quickly became the first star of Viennese art films , played in "The Pastor of Kirchfeld" . A little later "Frau Gertraud nameless" followed , where he was at the side of the popular actress Hansi Niese , who had already played a small role in "Johann Strauss on the beautiful blue Danube" in 1913, and with the director of the theater in the Josefstadt , Josef Jarno , was married, plays. Also in 1914 there was a monumental production by the French director Pierre Paul Gilmans , “Speckbacher” , which dealt with the Tyrolean struggle for freedom against Napoleon. Original Speckbacher sabers and 2000 extras, also carrying historical weapons, were used for the recordings, in which members of the Exl stage such as Eduard Köck were also involved . It was Austria's first large-scale production - the Viennese producer Jupiter Film went bankrupt after the film was finished.

In 1914, 25 years after the completion of Bertha von Suttner's novel Die Waffen Nieder , this novel by the 1905 Nobel Prize winner was filmed by Holger-Madsen in Copenhagen , the capital of the then important film production country Denmark . However, the first performance took place in September 1915, right in the middle of the war during the First World War.

In the first years of Austrian film production, around 130 short and longer feature films were made up to 1914, many of them based on their own ideas or original books from home, some - especially when it came to technology - also influenced by foreign countries, especially France. There were also over 210 documentaries. The spectrum of Austrian filmmaking ranged from short documentaries and weekly news reports, small folk plays, drama adaptations and family dramas, crime stories, operettas and historical large-scale films to grotesques.

The Austrian film historian Walter Fritz stated on Austrian filmmaking in the prewar period: “The thoughts of the historian Johnston on the creative power of the monarchy, which apparently saw itself as a 'happy apocalypse', show that a final mood prevailed, which was and was seen by the critics at the time had the strength to work to this day. "

During the First World War, 1914 to 1918

In the course of the mutual declarations of war by the major European powers that led to World War I , France also became the enemy of Austria-Hungary, which among other things resulted in the dissolution of all French film companies in the monarchy. At the same time, the import of foreign films was banned. In the following war years, the expected upswing in domestic film production occurred, but this happened much more slowly than expected.

In 1915 Sascha Kolowrat-Krakowsky was transferred from the Automobile Corps in Galicia to the war press headquarters in Vienna, where he took over the management of the film exhibition, which was subordinate to the war archive. He was able to win over numerous directors and other filmmakers to work, including the young talents Karl Hartl , Fritz Freisler , Gustav Ucicky and Hans Theyer .

In 1916, Kolowrat-Krakowsky had a hangar frame delivered from Düsseldorf in order to set up the first large film studio in Sievering , which was already missing from some directors . It was the first free-standing film studio in Austria. On April 4 of that year, the previously loose collaboration between Kolowrat-Krakowsky and Oskar Messter resulted in the "Oesterreichisch-Hungarian Sascha-Meßter-Film Gesellschaft mbH", later Sascha-Meßter-Film .

Emperor Franz-Joseph died in 1916 , and the politically inexperienced Karl became his successor. In contrast to his great-uncle, he was often at the front, as shown by some footage. On these he can often be seen in conversations with soldiers and awarding medals. Regardless of rank or rank, the imperial couple shook hands informally. With the help of cinema and film, it was easier for Karl to accept his role as People's Emperor. In 1917, Emperor Karl appointed Eduard Hoesch his personal operator (cameraman). In the propaganda film “Our Emperor” you can even see Karl praying for the good fortune of his troops in arms.

In 1916 the first edition of Paimann's film lists appeared - more precisely, at that time it was still letters that Austrian cinemas reported on the new releases of films, and provided a summary of the content and reviews. It was not until 1921 that Paimann's film lists became a periodical publication that appeared until 1965.

The later NSDAP member Heinz Hanus , one of the pioneers of Austrian film, founded the “Association of Film Directors and Cinematographers” that year.

Development of film production

In addition to the countless newsreels and dozen of propaganda films that were produced during the five years of the war, other changes in film production also made themselves felt. Hardly any detective films were produced, and grotesque fun games , which were very popular until recently, almost completely disappeared from cinemas. Instead, social dramas, more difficult literary comedies and costume films were booming. After the start of the war there was a slump in the number of films shown, which was due to the import ban on films from hostile nations such as France, Great Britain or the United States. But until 1918, when the cinemas could no longer be heated due to a lack of coal, and a lack of raw film put film production in trouble, the number of domestic productions rose annually, which profited greatly from the lack of foreign competition.

Ludwig Anzengruber's works , which often took place in a rural setting, were particularly popular among literature sources. Of these, among others, The Perjury Farmer (1915), In The Spell of Duty (1917), The Schandfleck (1917) or The Double Suicide (1918) were filmed with great success. As film reviews of the time described the actions, variety, scripts and directing practices, Austrian film production has developed significantly at that time. The scripts were more elaborate and the plot was easier to understand despite the greater complexity.

Towards the end of the First World War, films were made in Austria, many of which were anticipated in German expressionist films of the 1920s. For example in The Snake of Passion from 1918, which is very similar in style and subject matter to the German film Der Blaue Engel (1930) but also to Carl Theodor Dreyer's Vampyr (1932). Other pre-expressionist films were The Mandarin (1918), The Letter of a Dead (1918), The Waning Heart and The Other Self (1918). The screenwriters and directors Carl Mayer , Hans Janowitz and Fritz Freisler were the main representatives of pre-expressionist film in Austria . Well-known actors at the time were the eccentric Harry Walden and Carl Goetz , who played leading roles in Der Mandarin , a production of the Sascha-Film by Paul Frank and Fritz Freisler.

In the years before, Wiener Kunstfilm and Sascha-Film or Sascha-Meßter-Film were the largest domestic production companies, but space was offered to new companies in isolated Austria-Hungary. With Filmag , A-Zet Film , Astoria-Film and Leyka Film , new producers were able to assert themselves on the market. In 1913, the later director of the Decla Film Society in Berlin , Erich Pommer , founded the “WAF” - the “Wiener Autorfilms” production company. The propaganda documentation “Our War Fleet” , which was first performed on May 22, 1914, can also be traced back to WAF . Before that, in 1911 he took over the agendas of the Société Eclair.

While around 120 films were produced between 1906 and 1914 (44 of them in 1914), during the war years it was between 180 and 190. 100 Austrian feature films were made in 1918 alone - a figure that was even exceeded in the interwar years. In addition, there were a large number of war newsreels , which were also shown in the cinemas. After a comedy by Rudolf Österreicher and Bela Jenbach , "Der Herr ohne Wohnung" appeared with Gustav Waldau in the leading role in December 1915 . The brothers Conrad and Robert Wiene , who later both enjoyed great success in Germany, also worked as directors .

In 1914 Robert Müller , owner of the film production company of the same name, made his first attempts at animation. He engaged the draftsman Theo Zasche, who produced several, partly anti-Semitic, propaganda caricatures for the cinema (e.g. When the Russian stood in front of Przemysl , The New Trinity , The Tsar and His Dear Jews ). In the following years, Ladislaus Tuszyński and Peter Eng, two more versatile representatives of the first Austrian attempts at animation, appeared. Right from the start, experiments were also carried out with mixing elements of animated films with real recordings, for example when the hand of the illustrator Louis Seel covers the naked woman he has just drawn in a bathtub. Austria's only film company which, in addition to regular feature films, also produced animated films on a regular basis and on a large scale, was Astoria-Film. Tuszyński made some of his films in-house. Almost all Austrian animated films of the silent film era came from the pen of Tuszyński, Eng and Seel.

Of all the films produced during the First World War, recordings of only four films exist.

First movie stars

What made film stars so special at the time was that they could live on the fees from the film business without having to work in theaters on the side. The fees for the films therefore had to be correspondingly higher if actors did not come from the theater and did not pursue any other activities, which would have been difficult anyway with the abundance of film productions. Seen in this way, two film stars emerged in the course of the increasing number of domestic productions during the First World War: Liane Haid at Wiener Kunstfilm and Magda Sonja at Sascha-Film . There were no male film stars in this sense, but there was an abundance of busy male actors who, however, could not make a living from film on their own, and mostly pursued theater acting or cabaret on the side. Some of the most famous of these were Hubert Marischka , Georg Reimers , Franz Höbling , Otto Tressler and Willy Thaller . There were other stars only at the theater, although these could occasionally be won over for film appearances, such as Hermann Benke , Karl Baumgartner , Hermann Romberg , Josef Reithofer , Anton Edthofer , Friedrich Fehér and Hans Rhoden .

1915 was the year Austria's first film star got his first role. Liane Haid played a double role in the propaganda film "With heart and hands for the fatherland" . In contrast to other busy actors at Wiener Kunstfilm, she received 200 kroner a month from the start, instead of the usual 150. The production company gradually built her into a star, and by 1918 the monthly fee rose to 400 kroner, which she nevertheless did not prevent her employer from suing. She called him "exploiter" and admitted that she had contracted acute lung catarrh and pleurisy during the filming . She also complained about the costumes, although it was not even common for many other production companies to have their own costume designer, like the one Wiener Kunstfilm had. From time to time it was also possible to borrow costumes from theaters.

In 1917 Liane Haid starred in “ Der Verschwender ” , a film adaptation of a play by Ferdinand Raimund . With a play length of 3400 meters, this was the longest Austrian production to date. With this, Wiener Kunstfilm lived up to its pioneering role before Sascha-Film, as in many other areas. Liane Haid's appearances in this feature film were praised by the critics for their naturalness and the “authenticity of the characterization of an elderly family mother”. After the First World War, Haid's father Georg had her own film studio built for her in Schönbrunn, which still exists today. Liane Haid later made numerous other films for other film companies. Her successor as a film star at Wiener Kunstfilm was first Dora Kaiser , who came from A-Zet-Film , and a little later Thea Rosenquist . At Sascha-Film, the most popular actress at that time was Magda Sonja . The Danish actress Eva Roth , who worked in several Austrian productions before the First World War, thought about the effect of the mask design in the film .

Propaganda films

As head of the film exposure, responsible for propaganda films, Sascha Kolowrat-Krakowsky had the necessary employees and actors from the film industry assigned to the war press headquarters. Most of the Austrian filmmakers at the time escaped death and imprisonment in the war. A well-known exception, however, was Max Neufeld , who could only reappear as a hero and lover after his military service. Some of the propaganda documentaries and films were "The Liberation of Bukovina" , "War at 3000 Meters Altitude" , "Day of Fight among the Tyrolean Imperial Hunters" and the two-part series "The Economic Development of Montenegro" and "The Collapse of the Italian Front" . These films were nevertheless checked by the censors. For example, close-ups of Italian soldiers undergoing medical treatment or fallen with "distorted faces" had to be cut from the films.

A well-known propaganda film by the "Sascha-Messter", which was supposed to teach skeptics and war opponents "wrong", was about a complainer who saw in a dream the efforts of the soldiers in the war, which shook him very much. When in “reality” two boys have too little money to be able to subscribe to war bonds, he gives them the money and also draws himself. Other noteworthy propaganda films were the “Wiener Kunstfilm” productions “The Dream of an Austrian Reservist” (1915 ), “With heart and hand for the fatherland” (1915), “With God for the emperor and empire” (1916), “Free service” (1918). The unfinished documentary entitled “ Feldbach POW Camp ” never came into the cinemas .

The film production company "Robert Müller" had Alfred Deutsch-German produce "The Godfather" (1915). "A-Zet Film" contributed to the propaganda film production with "The Child of My Neighbor" and in 1918 "Filmag" had "Konrad Hartl's life fate" recorded with director Karl Tema . The quality of such films naturally took a backseat, as it was only a matter of arousing and maintaining enthusiasm for war among the population. The film reviews only knew good films and raved about the content. In 1918, Sascha-Meßter-Film dared to film a work by Beethoven . Fritz Kortner played Beethoven so well in “ The Martyr of His Heart ” that he subsequently advanced to become one of the most important expressionist actors in German-speaking countries.

For example, recordings were made in the large, newly built “Sascha-Film” film studio in Vienna-Sievering, where trenches were dug. More often than before the war, the film music came from well-known composers such as Franz Lehár and Carl Michael Ziehrer , who, like many other cultural personalities of the time, were inspired by the war.

Rare, but all the more prominent, criticism of the propaganda films came from Karl Kraus , who publicly criticized the war press headquarters , the “Sascha-Film”, Hubert Marischka , fellow poets and newsreel operators.

War newsreels

In September, the produced Viennese art film , the first war newsreel of the country : the "War Journal" . After the publication of the first eight editions, Sascha-Film, together with “Philipp und Pressburger” and the “Oesterreichisch-Ungarische Kinoindustrie Gesellschaft”, entered the market with the publication of their first war newsreel. This was called the “Austrian weekly cinema report from the northern and southern theater of war” . Despite the dissolute title, this newsreel was more successful. In 1915 it was referred to as "Cinematographic War Reporting" , then "Sascha War Weekly Report" . The “Sascha Messter Week” was also published at the same time .

Late silent film era, 1918 to 1930

| Silent film production of short and longer feature films |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | number | ||||||

| 1908 | 1 * | ||||||

| 1909 | 0 | ||||||

| 1910 | 6th | ||||||

| 1911 | 10 | ||||||

| 1912 | 24 | ||||||

| 1913 | 39 | ||||||

| 1914 | 61 | ||||||

| 1915 | 30th | ||||||

| 1916 | 24 | ||||||

| 1917 | 54 | ||||||

| 1918 | 88 | ||||||

| 1919 | 130 | ||||||

| 1920 | 142 | ||||||

| 1921 | 120-135 ** | ||||||

| 1922 | 130 ** | ||||||

| 1923 | 35 | ||||||

| 1924 | 32 | ||||||

| 1925 | 35 | ||||||

| 1926 | 19th | ||||||

| 1927 | 21st | ||||||

| 1928 | 28 | ||||||

| 1929 | 23 (+ 1 sound film) | ||||||

| 1930 | 24 (+ 3 sound films) | ||||||

| 1931 | 16 (+ 8 sound films) | ||||||

|

* Existence of the film controversial ** of which 70 to 75 feature films each |

|||||||

The inflation that set in after the First World War spurred Austrian film exports , so that for a few years Austria was one of the most important film nations in Europe after Germany . This heyday of the Austrian silent film subsided again significantly from 1923 when inflation was brought under control and the currency could be stabilized. Film imports , which flowed in mainly from the United States , were now cheaper again and many of the newly founded Austrian film production companies went bankrupt. Film production fell to a level of 20 to 30 films a year that was appropriate for the size of the country, and this remained so until the end of the silent film era. While the cinemas began to switch to sound films as early as 1927 (and this was completed in 1931), the film production companies took longer to produce the first sound film until 1929 - from 1932 onwards, silent films were no longer made.

The film productions of the 1920s were very diverse. In addition to standard productions such as comedies, melodramas and thrillers, Austrian filmmakers made significant and early contributions to expressionist film , which is mostly only attributed to Germany. Mid 20's there was a boom of monumental films , mostly from the Hungarian-born and in Vienna for Sascha- and Vita-Film make Michael Curtiz and Alexander Korda was born and involvements of thousands of extras produced the largest and most elaborate films, which were ever made in Austria. Also new objectivity films as well as reconnaissance and later mores films that attracted with permissive actresses came to the Austrian silent film era. Numerous film talents in a wide variety of positions, from cameraman to actor to director, began a career in the Vienna of the silent film era, which was soon continued in Berlin and often also in Hollywood (see section Migration of the silent film era ).

Film production soared

After the break-up of Austria-Hungary, Austria was the only one of the successor states that could gain importance on the world film market. After the end of the war, after the end of the war, there was a real boom in Austrian film production. The strong devaluation of the krona due to inflation resulted in better opportunities for Austrian film producers in the now so important export market. Because in Austria, which has now shrunk to six million inhabitants, films could only bring in around 10 percent of the production costs on average. The export market, above all consisting of the successor states of the monarchy and Eastern Europe in general as well as the Orient, Italy, France, Spain, Scandinavia, South America, England and of course Germany, was now of particular importance. In contrast to the producers, the film distributors almost collapsed. The licenses for Austria-Hungary, which had around 1,400 cinemas, were now invalid. Inflation also made film imports an unaffordable endeavor.

In 1919, 30 production companies were founded, in 1922 there were already 50. The leading producers in these years were Sascha-Film , Astoria-Film , Listo-Film , Micco Film , Mondial-Film , Schönbrunn-Film , Vita-Film and Dreamland -Film . Film , all of which also had their own studio facilities - in Sievering (Sascha), on the Hohe Warte (Astoria, Listo, Mondial), in Schönbrunn (Micco) and on the Rosenhügel (Vita). Austrian film production reached unprecedented heights between 1918 and 1922, when up to 75 feature-length films and another 50 to 60 one-act plays were produced and distributed worldwide. Not counting here are the numerous educational, cultural, documentary and propaganda films. Although the equipment of the Viennese film studios lagged behind the German competition, equally large effects and films could be produced with simpler means. During this time, numerous actors experienced a career upswing due to the enormous film production, but for many only temporary. The British film theorist L'Estrange Fawcett even said in his book Die Welt des Films , published in 1928 , that the city of Vienna is “better suited than any other in Europe” to “developing into a European Hollywood. The wonderful monuments, especially from the Baroque period, the incomparable beauty of the Viennese landscape, the nearby high mountains and the excellent climatic conditions make Vienna a city of films. "

In fact, in the years after the First World War, when European film production, with the exception of Germany, was largely down, Austria was among the leading film producers in Europe. The European film countries that dominated before the World War, Great Britain, France and Italy, as well as Denmark and other European countries, could hardly achieve the extent of Austrian film production and export activities. However, Vienna was far from a Hollywood of Europe, which would most likely have been applicable to Berlin, especially since the currency reform soon contained inflation, stabilized exchange rates and thus destroyed Austria's competitive advantage. What was an export problem for Austrian producers was a relief for foreign film producers. Austria received a veritable flood of films, especially from the United States. As early as 1923, many of the still young film companies collapsed and many more, which banks and investors viewed only as objects of speculation, went bankrupt in the spring of 1924 when the Vienna stock market crashed.

Film economic crisis due to enormous US competition

After the most productive years in 1921 and 1922, film production began to decline rapidly again in 1923. In 1924 only 32 films were produced, compared to around 130 in 1922. The lavish monumental films were only the financial and qualitative high point of this time, because US film productions had long since made Austrian films increasingly competitive in the cinemas. The American film industry brought in the production costs in the United States and was able to throw its films on the market worldwide at the lowest prices. Since the quality of American films had steadily increased, not least due to the constant immigration of European filmmakers and their knowledge, while the quality of the European film industry was almost at a standstill during the First World War, there was little to oppose to US productions.

In 1925, US dominance, which had already hit France, England and Italy, also reached Austria. This year, 1200 US productions and around 800 from other countries were approved for import by the censorship authority, while in Austria only 35 feature films were produced in the studios that were now technically well equipped. The film requirements of the 750 Austrian cinemas were estimated at only 300 to 350 films. Numerous production companies closed at that time, and around 3,000 filmmakers (directly and indirectly dependent on film) became unemployed. At the same time, however, the number of distribution companies rose to around 70, with smaller Austrian distributors as well as film production companies perishing.

On this occasion, the Filmbund called for a demonstration at the beginning of May, which was joined by around 3,000 artists, musicians, performers, workers and employees as well as traders in the film industry. Including greats such as Sascha Kolowrat-Krakowsky , Jacob and Luise Fleck , Walter Reisch , Magda Sonja , Michael Kertész , Hans Theyer and many others. The demonstration moved from Neubaugasse via Mariahilfer Strasse to Parliament . This made the federal government aware of the threat to the existence of the Austrian film industry, and a two-year film quota law came into force on May 19 . From now on, at least 75% of the employees in Austrian film productions had to be Austrians, and the import of foreign films was subject to quotas and, following the German model, linked to the number of domestic productions (at the beginning 1 domestic feature film to 20 foreign ones, then between 1:10 and 1 : 18). Although the era of mass productions was over, the continued existence of the domestic film industry, albeit in a scaled-down form, was secured. Some foreign productions could also be lured to Austria, as the production costs here are around 30% lower than in neighboring countries.

Nevertheless, most of the Austrian filmmakers finally moved to Berlin - the “Hollywood of Europe”. Only Sascha-Film, with Sascha Kolowrat-Krakowsky's family fortune in the background, was still able to produce large-scale productions.

Expressionism in Austrian film

The expressionism in film, mostly attributed to Germany in film historiography, also found its roots in Austrian productions. Jakob and Luise Fleck's “The Snake of Passion” from 1918 is now accepted as the first film ever to use expressionist stylistic devices . Although the film, like many other silent films, has no longer survived, which makes research extremely difficult, the dramaturgical construction of the fever nightmare, through which the main character is purified, speaks for this assumption. Films prior to “ Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari ” (1920), the most successful expressionist film made, are often referred to as“ pre-expressionist ”.

In 1920 Paul Czinner's “most important” film appeared - as he said in retrospect on television in 1970 - during his creative time in Vienna: the pre- expressionist film “Inferno” . In Berlin, at that time a career springboard for numerous Austrian filmmakers, he kept in touch with the Austrian authors Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz , who were currently working on the template for “ Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari ” as well as for Fritz Lang , who was just staging “ The Lord of Love ” and was at the beginning of his successful career. They all have in common the expressionist influence in their works. Czinner also reported that he wanted movement in the film and had a camera mounted on a tricycle for this purpose . This is said to have been the first driving recording, which was then used and further developed worldwide.

In 1924 the pan film production “ Orlac's hands ” appeared with the expressionist actors Conrad Veidt as “Orlac” and Fritz Kortner as “Nera”. Directed by Robert Wiene . A second well-known and well-researched representative of Expressionist film in Austria was Hans Karl Breslauer's film adaptation of Hugo Bettauer's novel “ The City without Jews ” , which was also released in 1924. The striking difference to the novel is that “the city” is not called Vienna, but “Utopia”. One of his first roles was given in this film by Hans Moser . The director's wife, Anna Milety , also served as the main actress in this film . The well-known Jewish actors Gisela Wergebiet and Armin Berg were only seen in smaller roles in this film.

One of the last expressionist films in Austria was “Das Haus des Dr. Gaudeamus ” . Contemporary reporting and descriptions of the decorations indicate the expressionist design of the no longer preserved film.

New objectivity and further filmmaking from the 1920s

Based on the social reports of the journalist Emil Kläger from the Viennese sewer system and other places of refuge for the homeless and unemployed, the film "Through the Quarters of Misery and Crime" was produced, which was released on June 25, 1920 in cinemas in Vienna. This film is likely to be Austria's first filmed social report. In the following years, feature films were also released that dealt with the dreary situation in inflation-ridden Austria after the First World War: "Women from the Wiener Vorstadt" (1925), "Haifische der Nachkriegszeit" (1926), "Saccho und Vanzetti" (1927) , “Other women” (1928), “A whore has been murdered” (1930), to name a few.

As early as 1921 a film was released that addressed recent Austrian history: "Kaiser Karl" with Josef Stätter as the main actor and Grit Haid , Liane Haid's sister, as his wife "Zita". The film “Leibfiaker Bratfisch” dealt with the death of Crown Prince Rudolf in 1925 and reproduced the memories of his fiaker . The director Hans Otto Löwenstein used many scenes from his Mayerling film, which was banned in 1919 . He also directed “Kaiser Karl” . In the same year "Colonel Redl" was published , which addressed an espionage case in 1913. The themes of both films have also been taken up again in recent Austrian film history. In 1921, 25 years after the publication of the utopian work “ Der Judenstaat ” by Theodor Herzl , a tribute to this author and psychologist appeared: “Theodor Herzl, the standard-bearer of the Jewish people” . The main actors were Rudolf and Josef Schildkraut in the historical part of the film, and Ernst Bath as Theodor Herzl.

The most famous film adaptation of a Hugo Bettauer work, however, was the 1925 production “ Die joudlose Gasse ” under director GW Pabst . The film, which is still shown internationally as a representative of early filmmaking, first appeared in cinemas after Hugo Bettauer was murdered by an NSDAP member. The film was recorded in Berlin studios, with actors such as Greta Garbo , Asta Nielsen and Werner Krauss . He played in present-day Vienna, which is heavily influenced by inflation, and is internationally regarded as the starting shot for the New Objectivity style in film. It also had its German premiere in Berlin - where GW Pabst spent their main creative time alongside Fritz Lang , Paul Czinner and other Austrians - in the “Mozartsaal” cinema. In France, Pabst achieved almost more fame with this film than in German-speaking countries. It appeared under the name “La rue sans joie” and was premiered on January 21, 1926 in the Parisian Studio des Ursulines .

Enlightenment and freedom of movement as new film topics

In the course of the emerging more revealing fashion in everyday life and the "New Objectivity" as a reality-related style in many areas of art, the established film companies now also dared to make for the first time more revealing films. So appeared Anita Berber than poor clad dancer in "wisps of depth" (1923), and " Café Elektric " were not only Marlene Dietrich provided detail on display, but also extended kissing scenes with legs Willi Forst shown.

The 1920s became the "golden age" of educational and moral films . Films made use of physical freedom as well as dream and mad scenes. In relation to this, “Was ist Liebe?” Appeared in 1924 with Dora Kaiser and Carmen Cartellieri and “Moderne Vast” on alcoholism. In 1928 another Hugo Bettauer film was released with “Other Women” .

While Enlightenment films dominated between 1918 and 1924, films from 1927 were more marked by voyeurism . The first educational film appeared in 1918 and dealt with hereditary diseases: "The scourge of humanity" . As in so many styles of film, the Viennese art film industry was a pioneer this time too . However, internationally recognized educational films were also made by the State Federal Film Headquarters , such as Narkotika , a film about drugs that was shown in major cinemas in Geneva for about three weeks. Of the private film companies, the pan film with educational films stood out. Her productions such as “Alcohol, Sexuality and Crime” , “Hygiene of Marriage” and “How do I tell my child?” Excelled in the popular science field. With "Paragraph 144" the termination of pregnancy was also addressed in a film production. Many of these educational films were directed by Dr. Leopold Niernberger , with the help of learned professors.

From 1924 onwards, hardly any films came out of the field of the Enlightenment. In 1927 the area was revitalized in other ways. It appeared "From the house of joy to marriage" and 1930 "Eros in chains" . In 1930 the actress and dancer Anita Berber died , who until then had caused a sensation in Viennese variety theaters with half-naked or nude appearances. This was documented in 1923 in "Dances of Horror and Vice" . However, the film is no longer preserved.

Elaborate monumental films

At the beginning of the 1920s, monumental films also came into fashion in Austria . The reason was of course business interest, as such exotic large-scale productions, in which nude scenes were featured in addition to unprecedented mass scenes and detailed backdrops and costumes, attracted the audience in droves. There was also interest, especially since the tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun was discovered in 1922 , which caused a sensation worldwide and triggered a veritable fashion wave.

As early as 1920 Sascha Kolowrat-Krakowsky had the film city "Old London" built in the Vienna Prater, west of the rotunda. There Alexander Korda shot “Prince and Beggar Boy” , based on a novel by Mark Twain . In 1922, Alexander Korda's production "A Sunken World" even received a film award in Milan.

In 1922 the monumental film " Sodom and Gomorrah " was released , produced by Sascha-Film Sascha Kolowrat-Krakowskys. This was in 1918 in the United States to examine the film industry there. It was there that he had the idea of producing monumental films with a large number of extras in Austria , as these were very popular in the USA at the time and he also had the USA in his sights as a sales market. The film, produced from 1920 to 1922, was directed by Michael Kertész, who later called himself Michael Curtiz in the USA , and his wife, the Hungarian Lucy Doraine , played the leading role.

The film is unique in Austrian film history because of its size during the shooting. The American monumental films, the Italian antique films and the German costume films were all to be outbid. Hundreds of craftsmen and technical and artistic employees found employment during the three years of filming in Austria, which is characterized by inflation and unemployment, as did thousands of extras. Thousands of costumes, wigs, beards, sandals, tinsel jewelry, standards, teams of horses and the like were made especially for the production mostly on site. The architectural masterpiece was the "Temple of Sodom" designed by three architects, which was one of the largest film structures in the world at this time. Little wonder that “Sodom and Gomorrah” became one of the most expensive films ever made in Austria. Still, it cost about five times what was planned. At the end of the film the temple should collapse, which is why pyrotechnicians were hired to blow it up. Nevertheless, mishaps occurred, in which there were even deaths and injuries, which also had legal consequences. The director was acquitted, the "tub maker" (artificial fireworks) sentenced to ten days' arrest and a fine of 500,000 kroner. The boom in Austrian film production also resulted in the establishment of a number of specialist companies. The “Schmiedl Equipment Institute” opened on September 19, 1919 and from now on lent out almost everything that could be used in a film: crockery, decorative art objects, costumes and much more. The "Wiener Werkstätte für Dekorative Kunst Ges.mbH Wien" had existed for a long time and already had a large number of costumes from film productions in stock in recent years.

In 1923 Vita-Film opened the largest and most modern Austrian film studios on Rosenhügel in Mauer . Construction began as early as 1919; the property and parts of the complex that had already been completed were playable even before that. It was there that Vita-Film, the successor company of the Viennese art film industry , shot the monumental film “ Samson and Delila ” for 12 million crowns in 1922 . The director was Alexander Korda . As with "Sodom and Gomorrah" , the director's wife also played the leading role in "Samson and Delilah" . The powerful Samson was played by Alfredo Gal .

In 1924, “ Die Sklavenkönigin ” divided the Red Sea in the middle of Vienna . Skillful modeling of the backdrops and post-production with trick technology ensured a deceptively real effect of the scene, which was not only enthusiastically received by the audience, but also by national and international critics. María Corda was seen as a revealingly dressed leading actress . Again directed by Michael Kertész. With production costs of 1.5 billion crowns, it was one of the most expensive films ever made in Austria.

In 1925, “Salammbô - The Battle for Carthage” was the penultimate monumental film, the Sascha-Film. With “Harun al Raschid” , which appeared in the Fritz Lang film “ Dr. Mabuse, the player “was modeled on, but another major project was created. Again directed by Michael Kertész.

In 1925, Pan-Film made a large-scale production of a different kind with “ Der Rosenkavalier ” , based on the opera of the same name . The film, directed by Robert Wiene , took place in baroque Vienna and came up with countless costumes, wigs and around 10,000 extras. For the film music, which was recorded separately on a record, came from Richard Strauss as in the opera piece . Like the opera, the premiere also took place in the Dresden Semperoper on January 10, 1926. The last monumental film was completed by Sascha-Film in 1925: “The Revenge of the Pharaoh” . Changed public tastes made further monumental film productions unattractive.

Film production facilities outside Vienna

After the end of the monarchy, Vienna's importance as “Austria's film production city” increased even further. Depending on the film theme, the federal states only served as landscape backdrops, with Lower Austria being used disproportionately often for outdoor shots due to its geographical proximity. Attempts to compete with Viennese film in other cities were hardly successful. In Graz in 1919 the "Alpin-Film", in 1920 the "Opern-Film" under Adolf Peter and Ludwig Loibner and in 1921 the "Mitropa-Musikfilm" were founded. In Innsbruck the "Tiroler-Heimatfilm" was productive from 1921 and in Salzburg the "Salzburger-Kunstfilm" started its activity in 1921. What all these companies had in common was that they had only a short lifespan. Not least because it was founded shortly before the great crisis in European film production in the mid-1920s.

In 1919 he made the short films (600 to 800 meters) "The Jump into Marriage" with Ernst Arnold as the main actor and "The Straitjacket" with singers from the Graz Opera as actors. Both came from the "Alpin-Film". The films "Czaty" , "Die Schöne Müllerin" and "Schwarze Augen" were also produced in Graz . All three films were directed by Ludwig Loibner and produced by Mitropa-Musikfilm. A special feature of these silent films was that there were no subtitles, since instead singers and orchestra accompanied the film, for which Adolf Peter arranged ballad music by Carl Loewe and lied music by Franz Schubert . The coordination of the orchestra and singers to the film was of course problematic, which is why there is no evidence of any other performances apart from the premiere of the films on September 19, 1921.

Also in Styria, the documentary film pioneer Bruno Lötsch , father of environmentalist and museum director Bernd Lötsch , made his first recordings for the “Steiermärkische Filmjournal”, a newsreel in Graz's preliminary program, which appeared in 1920 . 1920 was also the year in which Vienna's Astoria-Film in Tyrol made two films based on works by Karl Schönherr with actors from Innsbruck's Exl-Bühne : “Earth” and “Faith and Home” , where the later extremely successful Eduard Hoesch still did the Hand crank of the camera operated. In 1921 the Tiroler Heimatfilm started its first production with “Um Haus und Hof” . This was a film adaptation of a drama by Franz Kranewitter with actors from the Exl stage and directed by Eduard Köck , who later appeared primarily as an actor.

In 1921 the Salzburger Stiegl brewery in Maxglan made agricultural buildings available to the newly founded “Salzburger-Kunstfilm”. The young film production company set up a laboratory and a film studio there . The documentary “Die Festspiele 1921” was immediately made, in which Alexander Moissi could be seen as “ Jedermann ”, Werner Krauss as “Death” and Hedwig Bleibtreu as “Faith”. The first feature film, “The Tragedy of Carlo Pinetti” with the main actor Alphons Fryland , won an award on January 29, 1924 in Vienna. A second should never take place, as the company with its headquarters in the hotel “Österreichischer Hof” went bankrupt in 1925 - in the middle of the worst crisis in Austrian silent film .

The last years of the silent film

| Silent film production short and long feature films |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | number | ||||||

| 1908-1913 | 80 | ||||||

| 1914-1918 | 257 | ||||||

| 1919-1922 | 522-537 | ||||||

| 1923-1931 | 233 | ||||||

| Total: | 1088-1103 | ||||||

In 1926, in addition to 19 feature films, the film magazine Mein Film was published for the first time , which from then on was one of the most influential Viennese film magazines until it was discontinued in 1956.

1925 produced the Sascha film The Toys of Paris with the French actor Lily Damita in the leading role. The film impressed with the abundance of magnificent evening dresses that came from the fashion house Ludwig Zwiback und Bruder . This was not forgotten to mention in the film magazines either. The domestic films with their well-known actors were often an effective advertising fashion show of the local clothing stores. In 1927 Sascha-Film produced The Pratermizzi . A predetermined success, given the fact that Sascha-Film was the only remaining major producer in Austria. The director was Gustav Ucicky and the leading actress was the "big boozer" , the American Nita Naldi . “Several bottles of French champagne, cognac and first-class schnapps always had to be ready in her cloakroom, otherwise she wouldn't play anything. While she was getting dressed and putting on make-up, she drank at least one bottle empty, after each scene another followed - mixed with glasses of schnapps […] To the bother, the already very battered woman fell in love with her then very young partner Igo Sym and attacked him, where it was possible. It already started during the drive to the studio, and there were wild seduction scenes in her cloakroom. "

The film Café Elektric followed in 1927 , for which Sascha Kolowrat-Krakowsky, who was now seriously ill with cancer, discovered Willi Forst and Marlene Dietrich as the main actors. The director was again the former cameraman Gustav Ucicky, who was able to assert himself with Die Pratermizzi and thus gained Sascha Kolowrat-Krakowsky's trust. Willi Forst credibly played an underworld thug, but only developed his likeable character in the sound films. And Marlene Dietrich, who was able to come up with her physical charms in many scenes in this first role, only achieved her unique charisma in the films directed by Josef von Sternberg .

In Germany in 1927, the Austrian director Fritz Lang, who worked for Ufa, made a world-class film with the socially critical science fiction classic Metropolis . It was also the most expensive film Ufa had ever financed, which temporarily put the film company in financial distress. Also in 1927, after studying law, the 20-year-old Viennese Alfred Zinnemann came to film through a camera training in Paris. He first went to Berlin as a camera assistant and emigrated to the United States in 1929, where he made a career as a director and producer from the late 1930s. He even received an Oscar for his short film That Mothers Might Live .

In 1927, 21 Austrian feature films were released; in 1928 the number rose to 28. There were 70 rental companies. In 1929 23 silent films and the first sound film were released, and in 1930 13 silent and 4 sound films. Including the silent film operetta Archduke Johann by director Max Neufeld, with German-national sayings in the subtitles . Another film about the Habsburgs was shown at this time with The Fate of the Habsburgs . In this German production Leni Riefenstahl played the mistress of Crown Prince Rudolf , Mary Vetsera .

In 1929, Fritz Weiß advocated the social status of tramps in his film Vagabund in a neorealistic manner . The young actors Walter Edhofer , Paula Pflüger and Otto Hartmann also worked in it . Recordings from real life were also used. In this work, Fritz Weiß orientated himself strongly on the Soviet revolutionary film , which he had carefully studied.

Migration of the silent movie era

In the interwar period, the Austrian and German film industries mixed more and more. Many Austrian filmmakers commuted between Vienna and Berlin or stayed there at all, such as Fritz Lang , Fritz Kortner and many others. But German filmmakers also made significant contributions to Austrian films in the 1920s, such as the director Robert Wiene . There was also an emigration movement to Hollywood, which often passed through Berlin as a stopover.

Some Austrians were able to start their US careers before the First World War. The first to be mentioned here is Joseph Delmont , who was filming on the east coast in the first decade of the 20th century. Much better known and more significant in terms of film history, however, is the career that Erich von Stroheim began as an actor in Hollywood in 1909 and ended as one of the most important directors. Josef von Sternberg began his Hollywood career in 1911 . However, he did not direct for the first time until 1924. In 1930 he gave Marlene Dietrich in Berlin the lead role in “ The Blue Angel ”, which started her world-famous career. The composer Max Steiner emigrated to the United States during the First World War, where he composed his first film music in 1916 and was discovered by Hollywood in 1929. Apart from the aforementioned, only a few others successfully emigrated to Hollywood during the silent film era - for most of them Berlin remained more interesting until the National Socialists came to power . The Viennese actor Georg Wilhelm Pabst started at the “Neue Wiener Bühne”, but played in New York from 1910 and was interned by the French during the First World War. However, he became known as a director in Berlin and Vienna after his Hollywood engagement was unsuccessful. The Viennese Fritz Lang began his career in Berlin, where he was one of the most important directors in the 1920s.

Richard Oswald worked as a film dramaturge in Berlin from 1913 , but only switched to directing a little later. As the founder of the educational film , he caused a sensation with the treatment of taboo topics such as abortion . Joe May staged operettas in Hamburg and from 1912 shot, among other things, the film series around detective Stuart-Webbs . In 1933 he too emigrated to Hollywood. His wife Hermine Pfleger , known by the stage name Mia May , went with him.

In addition to the well-known actors and directors, the emigrants also included many cameramen , screenwriters , technicians and producers . In the 1910s and 1920s, other Austrians , Franz Planer , Paul Czinner , Carl Mayer , Jakob and Luise Fleck , Edgar G. Ulmer , Fred Zinnemann , Peter Lorre , Billy Wilder and also Max Reinhardt, moved their main residence to Germany - to the European film metropolis Berlin .

Hans Theyer and Eduard Hoesch made a name for themselves as cameramen for newsreels and feature films worldwide, especially in Denmark. However, the majority of their work was carried out in Austria, where Hoesch became involved as a producer and director of Heimatfilme after the Second World War.

In the early 1920s, numerous Hungarian filmmakers also fled the Béla Kun regime to Austria, which is reflected in the film production. The most important directors of Austrian monumental films - Alexander Korda and Michael Kertész - were Hungarians. A few other big names in Hungarian film at the time who moved to Vienna at the time were Vilma Bánky , Michael Varkonyi , Béla Balázs and Oskar Beregi . Although the monarchy no longer existed, Austrian filmmaking was still shaped by many filmmakers from the former crown lands.

Concerning the emigration of domestic filmmakers and the relevant role of politics, the Hungarian-born film producer Josef Somló wrote in 1929: “From Fritz Lang to Stroheim a long line of Austrian film directors can be enumerated who are celebrities of the international film world abroad knows how many talents still have to wither inactive in Austria, because short-sighted tax legislation is robbing an industry that, like nothing else, seems to be able to reflect the culture of the homeland.

literature

German-language literature

- Michael Achenbach, Paolo Caneppele, Ernst Kieninger: Projections of Sehnsucht: Saturn, the erotic beginnings of Austrian cinematography. Filmarchiv Austria, Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-901932-04-6 .

- Helmut G. Asper: "Something better than death--": Filmexile in Hollywood; Portraits, films, documents. Schüren, Marburg 2002, ISBN 3-89472-362-9 .

- Walter Fritz : Cinema in Austria 1896–1930. The silent film. Österreichischer Bundesverlag, Vienna 1981.

- Franz Marischka: Always smile: stories and anecdotes from theater and film. Amalthea, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-85002-442-3 .

- Barbara Pluch: The Austrian monumental silent film - a contribution to the film history of the twenties. Thesis. Vienna 1989

- Gertraud Steiner: Traumfabrik Rosenhügel: Filmstadt Wien: Wien-Film, Tobis-Sascha, Vita-Film. Compress, Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-900607-36-2 .

Foreign language literature

- Doris Angst-Nowik, Jane Sloan, Cornelius Schnauber: One-way ticket to Hollywood: film artists of Austrian and German origin in Los Angeles (emigration 1884–1945): an exhibition. The Library, Los Angeles, Calif. 1986. (English)

- Robert von Dassanowsky : Austrian cinema - a history. McFarland, Jefferson (North Carolina) / London 2005, ISBN 0-7864-2078-2 . (English)

- Eleonore Lappin: Jews and film = Juden und Film: Vienna, Prague, Hollywood. Institute for the History of the Jews in Austria, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-85476-127-9 . (English)

- Willy Riemer: After postmodernism: Austrian literature and film in transition. Ariadne Press, Riverside (CA) 2000, ISBN 1-57241-091-4 . (English)

- Siegbert Salomon Prawer : Between two worlds: The Jewish presence in German and Austrian film, 1910–1933. Berghahn Books, New York 2005, ISBN 1-84545-074-4 . (English)

- Ernst Schürmann (Ed.): German film directors in Hollywood: film-emigration from Germany and Austria: an exhibit of the Goethe Institutes of North America. 1978, DNB 985605243 . (English)

See also

- Cinema and film in Austria - review article

Individual evidence

- ↑ Francesco Bono, Paolo Caneppele, Günter Krenn (eds.): Electric shadows. Filmarchiv Austria, Vienna 1999.

- ↑ Walter Fritz: I experience the world in the cinema . Vienna 1996, p. 54.

- ^ Lisi Frischengruber, Thomas Renoldner : Animated film in Austria. ASIFA Austria, Vienna

- ↑ a b Feature film production 1908–1918 based on: Anthon Thaller (Ed.): Austrian Filmography - Volume 1: Feature Films 1906–1918. Verlag Filmarchiv Austria, Vienna 2010, pp. 513–517 (annual film title register)

- ↑ a b Feature film production 1919–1929 based on: FRITZ, 1995.

- ^ Armin Loacker: Connection in 3/4 Time - Film Production and Film Policy in Austria 1930–1938. Scientific publishing house Trier, Trier 1999, p. 12f.

- ↑ L'Estrange Fawcett: The World of Film. Translated by C. Zell, supplemented by S. Walter Fischer. Amalthea, Zurich, Leipzig, Vienna 1928, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Fawcett, p. 144.

- ↑ For a discussion of the forerunners of expressionist film, see: Jürgen Beidokrat: The artistic subjectivity in expressionist film. In: Institute for Film Studies (Ed.): Contributions to German film history. Berlin 1965, pp. 71-87.

- ^ Thomas Ballhausen, Günter Krenn in: Medienimpulse. Issue No. 57, September 2006, pp. 35–39 ( online , PDF file; 433 kB)

- ^ Walter Fritz, Margit Zahradnik: Memories of Count Sascha Kolowrat. Vienna 1992, p. 32 f.

- ↑ Österreichische Filmzeitung, No. 9, February 23, 1929, p. 33.