Air France Flight 447

| Air France Flight 447 | |

|---|---|

|

Route of the Air France plane |

|

| Accident summary | |

| Accident type | Crash when stalled |

| place | Atlantic Ocean |

| date | June 1, 2009 |

| Fatalities | 228 |

| Survivors | 0 |

| Injured | 0 |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Airbus A330-203 |

| operator |

|

| Mark | F-GZCP |

| Departure airport |

Rio de Janeiro-Antônio Carlos Jobim , Brazil |

| Destination airport |

Paris-Charles-de-Gaulle , France |

| Passengers | 216 |

| crew | 12 |

| Lists of aviation accidents | |

The Air France Flight 447 (AF 447) was a scheduled flight of Air France from Rio de Janeiro to Paris , where on the night of May 31, June 1, 2009 Airbus A330-203 over the Atlantic crashed. All 228 inmates were killed. It is the worst accident in the history of Air France and the worst accident involving an Airbus A330. The final report of the accident investigation was published on July 5, 2012.

Plane and crew

The aircraft was an Airbus A330-203, serial number 660, registration F-GZCP, equipped with two General Electric CF6-80E1A3 engines . It had its first flight on February 25, 2005, and by the time of the accident it had completed around 18,870 flight hours. The last major maintenance took place on April 16, 2009. On August 17, 2006, the aircraft was involved in a ground incident when it rolled into an Airbus A321 at Paris-Charles-de-Gaulle Airport . The A330 was only slightly damaged.

216 passengers and twelve crew members were on board on the unfortunate flight. The captain Marc Dubois had a flight experience of around 11,000 hours, the two co-pilots David Robert and Pierre-Cedric Bonin around 6600 and 3000 hours respectively.

Flight history

The aircraft took off on May 31, 2009 at 19:03 local time (22:03 UTC ) from Rio de Janeiro-Antônio Carlos Jobim airport with destination Paris-Charles-de-Gaulle airport, from where it arrived at 11:15 local time (09: 15 UTC) should arrive. The aircraft flew to an area with known severe thunderstorms, such as are common in the intertropical convergence zone . Had the aircraft flew a detour to avoid to the weather, it probably would have a direct flight to Paris failed, but would stop over must. At 01:50 UTC, the aircraft left the coverage area of the Brazilian ATC radar north of the Fernando de Noronha archipelago . Within the next 10 minutes, the captain gave his place and his role as an assistant pilot and not actively steering to the first co-pilot, while the second co-pilot flew the aircraft as it had been since take-off.

Between 02:10 and 02:14 UTC, the aircraft sent 24 automatically generated maintenance messages to the Air France headquarters via ACARS . The analysis of these reports showed that most of them can be interpreted as a result of contradictions between the various speed measurement systems. Due to the different measured values, the autopilot was deactivated at 02:10:05 UTC by the on-board computer and the control computer switched to "Alternate Law", which means that certain parameters were no longer monitored by the electronics.

In addition to corrections about the roll axis of the pilot flying had raised the pitch in the first seconds, sounded even within those first few seconds twice a warning of coating from the stall warning system . Both pilots were then busy trying to analyze the error messages on the displays . Within the first 30 seconds, the non-flying pilot noticed a climb and asked the flying pilot to descend. The rate of climb then decreased somewhat, but the aircraft was still climbing and had already climbed 2,000 feet to 37,000 feet.

The failed speed specification was re-established after 29 seconds, and according to its specification, the aircraft had lost speed by around 50 knots in the 31 seconds since the autopilot had failed. Eleven seconds later, the thrust was slightly reduced and another four seconds later the stall warning sounded continuously. The thrust was set to TOGA , at the same time the angle of attack increased. The horizontal stabilizer moved within a minute up to + 13 °, where it remained until the end of the flight.

About one minute after switching off the autopilot, the aircraft was in an area outside of a possible safe operation due to altitude and speed and suffered a stall .

About one and a half minutes after the failure of the autopilot, the pilot, who had not been steering until then, took over the controls ("Controls to the left"), which was not confirmed and the right seat almost immediately took control again. Five seconds later the captain came back into the cockpit. At this point the aircraft was sinking at a rate of descent of 10,000 feet per minute, i.e. around 50 meters per second, which corresponded to an angle of attack against the airflow of 40 ° and was still in an upward position.

The situation remained unclear for all three pilots, it was only two minutes after his return to the cockpit that the captain realized that the flying co-pilot had pulled the elevator all the way to the stop.

The last ACARS message was sent at 02:14 UTC and concerned the air pressure in the cabin.

According to a press release from the French Civil Aviation Safety Investigation Authority ( BEA ), the last known position was transmitted via ACARS at 02:10 UTC. If the flight path is extrapolated, the position 4 ° N , 30 ° W results for the time of the last error message . The next position report at the district control would have been due at 02:20 UTC, but it did not materialize. The fuel carried would have lasted until around 11:00 UTC.

Search operation

The Brazilian Air Force ordered two aircraft ( Embraer EMB 110 Bandeirante and Lockheed C-130 Hercules ) stationed in Salvador and Recife to search the area of the Fernando de Noronha archipelago , which carried out flights from its airport to the crash site about 550 kilometers away. The frigate Constituição and the corvette Caboclo were also dispatched to the region. The Brazilian patrol boat Grajaú was the first ship to reach the suspected crash site. France took part in a long distance - Maritime Patrol Aircraft type Breguet Atlantic from Dakar from.

First search phase

A French AWACS reconnaissance aircraft of type E-3 Sentry flew over the region on June 3 to map with the radar system supposed wreckage and other traces of the crash. France also sent the research vessel Pourquoi Pas? , which can use the manned deep-sea submarine Nautile and the remote-controlled deep-sea robot Victor 6000 to examine the seabed at depths of up to 6000 meters. In addition, the helicopter carrier Mistral and the nuclear submarine Émeraude of the French Navy were on site from June 10, 2009 , primarily to support the search for the flight recorder (flight data recorder; FDR). The US sent a Lockheed P-3 Orion maritime patrol from Honduras to the area to aid the search in the Atlantic. On June 8, the US Navy made two highly sensitive tracking systems available to track down the flight recorder signals.

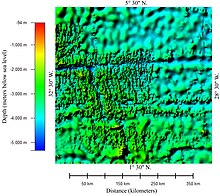

The flight recorder, the "black box", sent out an acoustic signal for at least 30 days to enable it to be located using sonar devices . The crash occurred in the area of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge , a submarine mountain range. The depth of the sea fluctuates in the area of the crash between about 1500 and 4500 meters (see graphic). The range of the sound signals is around two kilometers in the water, but the seabed there is very rugged, which, depending on the position of the flight recorder, can severely hinder the propagation of the sound signals.

On June 6, the first traces of the crash were found to be two male corpses as well as parts of the wreckage from the aircraft (including the rudder ) and pieces of luggage. The search was stopped on June 26 after nine days of finding no new wreckage or bodies. A total of 51 bodies and over 600 parts of the wreckage were recovered.

According to calculations by the accident investigators, the black box probably sent acoustic signals up to July 10, 2009. The search for the flight recorders with submarines and diving robots was stopped on July 11th for this reason.

Second search phase

The second search phase for the wreck and flight recorder was suspended at the end of August 2009. France had asked other countries for their help in the investigation.

Third search phase

The third search phase with experts from France, Great Britain, Germany, Brazil, Russia and the USA was planned for a period of 60 days and should start in February 2010; however, the start was delayed by a few weeks due to administrative and technical problems. The search operation was the most expensive search operation of the BEA and one of the most complex underwater search operations ever carried out. With a budget of around 10 million euros, almost 2000 square kilometers (770 square miles) of lake area were to be combed through. The search finally began at the end of March 2010. The US ship Anne Candies from Phoenix International, equipped with the deep-sea robot of the US Navy Supervisor of Salvage and Diving (SUPSALV) CURV 21 and the deep towed sonar device ORION, as well as the Norwegian ship Seabed Worker , took part in the search with the three AUVs REMUS 6000 and the robot Triton XLX 4000.

For the third search phase, the operating area was narrowed down from the original 17,000 to just 2,000 square kilometers. Since the ocean in the operation area is up to 4,000 meters deep and the seabed is very rugged, the participating experts did not rule out in advance that the search phase might have to be extended, which was confirmed by the BEA at the end of April 2010. On May 6, 2010, the BEA announced that a renewed evaluation of the data collected by the Émeraude in the summer of 2009 enabled the position of the black box to be narrowed down to an area of five square kilometers. The search was canceled on May 25, 2010.

Fourth search phase

Another search phase began on March 18, 2011, during which autonomous diving robots were to systematically search an area of 10,000 square kilometers in three stages of 36 days each. Airbus and Air France provided a total of 9.2 million euros for the search. The research vessel Alucia sailed from Seattle in the USA via the Panama Canal to Suape in the Brazilian state of Pernambuco , where it arrived at the beginning of March. On board were three unmanned, torpedo-shaped deep diving vehicles of the type REMUS 6000, which come from the Waitt Institute for Discovery in La Jolla in California and from the Leibniz Institute for Marine Sciences in Kiel and reach a depth of up to 6000 meters.

On April 3, 2011, at a depth of around 4,000 meters, a large field of debris was found on a flat spot on the sea floor, which apparently was the main wreckage of the aircraft involved in the accident. In addition to parts of the fuselage, wings, engines and chassis, bodies were also found.

On April 14, 2011, the media reported with reference to the BEA that the tail sections of the jet had been located during the evaluation of the robot images. The flight recorders are located in the rear of the aircraft.

Fifth search phase

To search for the flight recorders, the cable laying Île de Sein was brought to the site with the Remora 6000 diving robot (ROV) . On April 27, 2011, the BEA announced that the chassis of the flight data recorder (FDR) had already been found during the first dive of the Remora 6000 . However, the memory module (Crash Survivable Memory Unit) that contains the recorded data is missing.

On April 29, 2011, the BEA announced that the auxiliary power unit (APU) located in the rear of the aircraft had been found. The BEA also stated that the nose and tail of the aircraft had broken apart and these were scattered around. Attempts to recover these parts would not be made for the time being, as finding the flight recorder had priority.

Just two days later, on May 1, 2011, the memory module of the flight data recorder was discovered and recovered, as was the voice recorder (Cockpit Voice Recorder; CVR) the following day.

On May 16, the BEA announced that the data from both flight recorders could be read out. On June 3, the rescue work at the accident site was stopped.

Cause of accident

Interim reports before the data recorder was found

The BEA published the first interim report on July 2, 2009 and a second on December 17, 2009. It stated that the cause of the accident had not been clarified. The investigation results available at the time of publication of the second interim report allowed the following preliminary conclusions:

- The aircraft was largely intact until it hit the water. It was no longer possible to determine whether there were any minor damage.

- The aircraft hit the water in a nearly horizontal position, with its nose slightly above the horizon and without bank.

- The aircraft hit the water at high vertical speed.

- The aircraft was in cruise configuration.

- There was no pressure drop in the cabin before the impact.

- No preparations were made for a splashdown .

Final report

In 2011 the flight data recorder could be read out. The final report of July 5, 2012 came to the following conclusions:

The following events were responsible for the accident: The pitot probes measuring the speed of the aircraft failed temporarily, which was probably caused by clogging by ice crystals. As a result, the autopilot switched itself off and the flight controls switched to "Alternate Law" mode.

Although the pilots did not use the sidesticks, the aircraft rolled 8.4 degrees to the right within two seconds. For the next minute, the pilots were absorbed in keeping the plane under control. However, the pilots' control maneuvers were inappropriate and excessive in view of the “Alternate Law” flight mode and the altitude, and consisted primarily of pulling the aircraft up. This can be explained by a lack of training on how to manually flow this aircraft at high altitude in Alternate Law mode. The surprise effect of suddenly being confronted with this situation made things even more difficult. Since the autopilot shutdown signal was more insistent than the signal indicating the loss of the speedometer, the pilots instinctively searched for the cause of the shutdown of the autopilot and may not notice the signal indicating the loss of the speedometer. The first warning issued by the stall warning system was not taken seriously as such by either of the pilots. This reaction could also be observed in similar situations with other pilots. At high altitudes, even small changes in the flight parameters can lead to stalling.

The crew did not react to the signaled loss of the speed display with the intended procedure. The non-flying pilot (PNF = pilot non-flying) recognized too late that the flying pilot (PF = pilot flying) was pulling over the aircraft. After the non-flying pilot had warned the flying pilot, he corrected, but this maneuver was inadequate. The crew did not recognize the impending stall, and the crew did not react immediately. As a result, the limit of the area within which the aircraft could be operated was exceeded. The resulting stall situation was also not recognized by the pilots. As a result, no actions were taken that would have made it possible to counteract this.

The explanation given for this is the combination of the following factors: The pilots did not realize that they were not following the procedure to be used in the event of speed anomalies and could therefore not remedy the situation. In their hazard model, the authorities responsible for safety did not sufficiently take into account the risk that arises from icing up the Pitot probes and the associated consequences. There was no training in manual control at high altitude and how to react to speed anomalies.

The cooperation between the pilots was disrupted because the situation resulting from the deactivation of the autopilot was not understood. In addition, the surprise effect resulting from switching off the autopilot led to a high level of emotional stress on the two pilots. The inconsistencies in the speed sensors in the cockpit identified by the computers were not conveyed clearly to the pilots.

The stall warning issued was ignored by the crew. This could be the result of several circumstances: The type of audible alarm was not identified. Alarm signals at the beginning of the event were considered irrelevant and ignored. In addition, there was a lack of visual information that would have enabled confirmation of the impending stall after the loss of the speed display. It is possible that the pilots confused the present flight situation of too low a speed with that of too high a speed, because the symptoms of both conditions are similar. In addition, the pilots followed information from the flight command displays, which the crew confirmed in their actions, although they were incorrect. The pilots did not recognize or understand the consequences of the reconfiguration resulting from the change in the control electronics to the so-called "Alternate Laws" without any angle of attack protection system.

| Recording of the voice recorder and German translation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time ( UTC ) |

speaker | German translation) | French (original) | ||

| 02:03:44 | Bonin | The intra-tropical convergence zone ... OK, now we're in, between “Salpu” and “Tasil”. And then, ok, we're fully in it ... | La convergence inter tropicale… voilà, là on est dedans, entre 'Salpu' et 'Tasil.' Et puis, voilà, on est en plein dedans ... | ||

| 02:05:55 | Robert | Yes, we will call the back ... to let them know anyway, because ... | Oui, on va les appeler derrière ... pour leur dire quand même parce que ... | ||

| 02:05:59 | flight attendant | Yes? Marilyn here. | Oui? Marilyn. | ||

| 02:06:04 | Bonin | Yes, Marilyn - it's me, Pierre from the front ... Tell me, in two minutes we'll be in an area where the turbulence will be stronger than it is now. You have to be careful there. | Oui, Marilyn, c'est Pierre devant… Dis-moi, dans deux minutes, on devrait attaquer une zone où ça devrait bouger un peu plus que maintenant. Il faudrait vous méfier là. | ||

| 02:06:13 | flight attendant | OK. So shall we sit down? | D'accord, on s'assoit alors? | ||

| 02:06:15 | Bonin | Well, I think that wouldn't be bad ... notify the colleagues! | Bon, je pense que ce serait pas mal… tu préviens les copains! | ||

| 02:06:18 | flight attendant | Yeah, okay, I'll call the others in the back. Many thanks. | Ouais, Ok, j'appelle les autres derrière. Merci beaucoup. | ||

| 02:06:19 | Bonin | But I'll call you again as soon as we get out of there. | Mais je te rappelle des qu'on est sorti de là. | ||

| 02:06:20 | flight attendant | OK | OK | ||

| 02:06:50 | Bonin | Turn on the defrost. After all, that's something. | Va pour the anti-ice. C'est toujours ça de pris. | ||

| 02:07:00 | Bonin | Looks like we're at the end of the cloud layer, this should work. | On est apparemment à la limite de la couche, ça devrait all. | ||

| 02:08:03 | Robert | You might be able to pull a little to the left. | Tu peux éventuellement le tirer un peu à gauche. | ||

| 02:08:05 | Bonin | Sorry? | Excuse-moi? | ||

| 02:08:07 | Robert | You could possibly take the path a little further to the left. Do we agree that we fly manually? | Tu peux éventuellement prendre un peu à gauche. On est d'accord qu'on est en manuel, hein? | ||

| 02:10:06 | Bonin | I have the controls. | J'ai les commandes. | ||

| 02:10:07 | Robert | OK. | D'accord. | ||

| 02:10:07 | Robert | So what is that? | Qu'est-ce que c'est que ça? | ||

| 02:10:15 | Bonin | We don't have a correct ... We don't have a correct speedometer. | On n'a pas une bonne ... On n'a pas une bonne annonce de vitesse. | ||

| 02:10:16 | Robert | So now we've lost them, the, the, the speeds? | On a perdu les, les, les vitesses alors? | ||

| 02:10:27 | Robert | Watch your speed. Watch your speed. | Fais attention à ta vitesse. Fais attention à ta vitesse. | ||

| 02:10:28 | Bonin | OK, OK, I'm going to descend again. | Ok, ok, ever redescends. | ||

| 02:10:30 | Robert | Stabilize ... | Do stabilizes ... | ||

| 02:10:31 | Bonin | Yes. | Ouais. | ||

| 02:10:31 | Robert | Sink again ... We are going to continue to rise, according to him ... according to him you are rising, so sink again. | Tu redescends… On est en train de monter selon lui… Selon lui, tu montes, donc tu redescends. | ||

| 02:10:35 | Bonin | OK. | D'accord. | ||

| 02:10:36 | Robert | Sink again! | Redescends! | ||

| 02:10:37 | Bonin | And let's go, we're sinking again. | C'est parti, on redescend. | ||

| 02:10:38 | Robert | Careful! | Doucement! | ||

| 02:10:41 | Bonin | We are in ... yes, we are in the "climb" (note: climb). | On est en… ouais, on est en "climb." | ||

| 02:10:49 | Robert | Damn it, where is he ... um? | Putain, il est où… euh? | ||

| 02:10:55 | Robert | Damn it! | Putain! | ||

| 02:11:03 | Bonin | I'm in TOGA , yeah? | Je suis en TOGA, hein? | ||

| 02:11:06 | Robert | Damn it, is he coming or is he not coming? | Putain, il vient ou il vient pas? | ||

| 02:11:21 | Robert | We still have the engines! What the hell is going on? I don't understand what is happening. | On a pourtant les moteurs! Qu'est-ce qui se passe bordel? Je ne comprends pas ce qui se passe. | ||

| 02:11:32 | Bonin | Damn it, I'm out of control of the plane! I no longer have control of the plane! | Putain, j'ai plus le contrôle de l'avion, là! J'ai plus le contrôle de l'avion! | ||

| 02:11:37 | Robert | Control to the left! | Commandes à gauche! | ||

| 02:11:43 | captain | Eh ... what are you doing there? | Eh ... Qu'est-ce que vous foutez? | ||

| 02:11:45 | Bonin | We're losing control of the plane! | On perd le contrôle de l'avion, là! | ||

| 02:11:47 | Robert | We have completely lost control of the plane. That is completely incomprehensible ... We tried everything ... | On a totalement perdu le contrôle de l'avion… On comprend rien… On a tout tenté… | ||

| 02:12:14 | Robert | What do you think? What do you think? What do we have to do? | Qu'est-ce que tu en penses? Qu'est-ce que tu en penses? Qu'est-ce qu'il faut faire? | ||

| 02:12:15 | captain | Well i don't know! | Alors, là, je ne sais pas! | ||

| 02:13:40 | Robert | Pull up ... pull up ... pull up ... pull up ... | Remonte ... remonte ... remonte ... remonte ... | ||

| 02:13:40 | Bonin | But I pull up all the time! | Mais je suis à fond à cabrer depuis tout à l'heure! | ||

| 02:13:42 | captain | No, no, no ... don't pull up ... no, no. | Non, non, non ... Ne remonte pas ... non, non. | ||

| 02:13:43 | Robert | Then go into the descent ... So, give me the controls ... The controls to me! | Alors descends… Alors, donne-moi les commandes… À moi les commandes! | ||

| 02:14:23 | Robert | Damn, we're going to hit ... shit, that's not true! | Putain, on va taper… Merde c'est pas vrai! | ||

| 02:14:25 | Bonin | But what is happening here? | Mais qu'est-ce qui se passe? | ||

| 02:14:27 | captain | Longitudinal slope 10 degrees ... | 10 degrès d'assiette ... | ||

| 02:14:28 | End of recording. | ||||

Chesley Sullenberger's analysis

Aircraft Accident Expert Chesley B. Sullenberger believes that the accident would have been less likely to have happened in a Boeing . While Airbus equips its cockpits with sidesticks , Boeing, in contrast, uses classic control horns . These are mechanically coupled with each other, but not the sidesticks at Airbus. In a cockpit with control horns, each control input by one pilot is clearly visible to the other pilot, and the control horn is also moved comparatively strongly with each input. The recordings of the voice recorder show that neither the copilot seated on the left nor the right-hand seated co-pilot identified the aircraft's stalled condition, although stall warnings sounded 75 times. In order to recognize the mistake of the pilot flying to constantly stall the aircraft, the pilot not flying seated on the left should have kept an eye on the sidestick of the right pilot; A further complicating factor was that a comparatively small change in position of the sidestick is sufficient to bring the rudders from a neutral position to full deflection. As the cockpit recordings show, the captain standing behind the seats only noticed the excessive flight condition when Bonin exclaimed “but I pull myself up all the time”.

Inmates

228 people were on board: 3 pilots, 9 flight attendants and 216 passengers, including 126 men, 82 women, 7 children and one infant. They came from 32 nations, including: 72 people from France, 59 from Brazil, 28 from Germany, 6 from Switzerland and one person from Austria.

During the first search phase, 51 bodies were recovered from the surface of the sea and identified, including those of the flight captain. As part of the fifth search phase, two bodies were recovered from the wreck on May 5, 2011. After it was possible to identify them using the DNA , it was decided to recover the remaining bodies as well. According to reports, most of the European survivors were against, but most of the Brazilian survivors were in favor of a rescue.

| nationality | Passengers | crew | total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

61 | 11 | 72 |

|

|

58 (57) | 1 | 59 |

|

|

26 (28) | - | 26 (28) |

|

|

9 | - | 9 |

|

|

9 | - | 9 |

|

|

6th | - | 6th |

|

|

5 | - | 5 |

|

|

5 | - | 5 |

|

|

4th | - | 4th |

|

|

3 | - | 3 |

|

|

3 | - | 3 |

|

|

3 | - | 3 |

|

|

2 | - | 2 |

|

|

2 | - | 2 |

|

|

2 | - | 2 |

|

|

2 | - | 2 |

|

|

1 | (1) | 1 (2) |

|

|

1 | - | 1 |

|

|

1 | - | 1 |

|

|

1 | - | 1 |

|

|

1 | - | 1 |

|

|

1 | - | 1 |

|

|

1 | - | 1 |

|

|

1 | - | 1 |

|

|

1 | - | 1 |

|

|

1 (2) | - | 1 (2) |

|

|

1 | - | 1 |

|

|

1 | - | 1 |

|

|

1 | - | 1 |

|

|

1 (3) | - | 1 (3) |

|

|

1 | - | 1 |

|

|

1 | - | 1 |

|

|

1 | - | 1 |

| total | 216 | 12 | 228 |

Pilots

According to the BEA's published report, the pilots' experience was as follows:

| captain | First Officer (Copilot) (left) | First Officer (Copilot) (right) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location at the time of the accident |

Initially on a break | Supervising Pilot (PNF) | Controlling the pilot (PF), in the right position and flying the aircraft |

|

| nationality | French | French | French | |

| Surname | Marc Dubois | David Robert | Pierre Cedric Bonin | |

| Age | 58 years | 37 years | 32 years | |

| Medical certificate |

Displayed | October 10, 2008 | December 11, 2008 | October 24, 2008 |

| Date of Expiry | October 31, 2009 | December 31, 2009 | October 31, 2009 | |

| Hints | Compulsory use of corrective lenses | Compulsory use of corrective lenses | ||

| Year of Private Pilot License (PPL) | 1974 | 1992 | 2000 | |

| Year of Commercial Pilot License (CPL) | 1977 | 2001 | ||

| Year of Air Transport Pilot License (ATPL) | 1992 | 1993? | 2007 | |

| Year of joining the company | 1988 (with Air Inter ) 1997 (merger of Air Inter with Air France ) |

1999 | 2004 | |

| Year of the type rating for Airbus A330 / A340 |

February 2007 | April 2002 | June 2008 | |

| Number of flight hours |

total | 10,988 | 6,547 | 2,936 |

| on Airbus A330 / A340 | 1,747 | 4,479 | 807 | |

Legal processing

On March 12, 2010, a court in Rio de Janeiro sentenced Air France to an initial compensation payment. Accordingly, the company has to pay 840,000 euros to the survivors of a victim in Brazil, a public prosecutor from the state of Rio de Janeiro.

On September 28, 2010, a French court ruled to award the relatives of a flight attendant compensation of 20,000 euros. The judges assumed that the accident was caused by negligence. Although the final report was not yet in place, the court said the machine's speedometer had not failed for the first time. Thus the fact of negligent homicide is fulfilled.

At the beginning of September 2019, more than ten years after the accident, French investigating judges ordered the judicial proceedings against Air France and the manufacturer Airbus to be suspended. In their view, the aircraft accident is explained “by the unprecedented combination of several circumstances”. The judges stood up against the public prosecutor, who had wanted to bring the airline to court for negligent homicide. The investigators had accused Air France, among other things, of not having adequately trained the pilots. An association of relatives of the victims stated that they would lodge a complaint against the order of the investigating judge.

Effects

After the accident, this scheduled flight was given the new flight number AF 445 , under which it took off from Rio for the first time a week after the accident, on the evening of June 7, 2009. The flight continued to be served by A330-203 aircraft.

Ten “Safety Recommendations” were published in July 2011: “The first recommends that regulators revise the content of the training and inspection programs and in particular the introduction of specific and regular exercises for manual steering, stalling and its termination, including at high altitude to prescribe. "

attachment

Interim reports after the data recorder was found

Report of May 27, 2011

On May 27, 2011, the BEA published a four-page report on the first ascertainable facts from the data recorders.

Due to the evaluability of the voice recorder and flight recorder, the BEA assumed that the cause of the accident could be fully explained.

The report states:

- The composition of the crew corresponded to the operator's procedures.

- At the time of the incident, the aircraft's weight and center of gravity were within operating limits.

- At the time of the incident, the two co-pilots were in the cockpit and the flight captain was resting; the latter came back into the cockpit about 1 minute 30 seconds after the autopilot was switched off or 2 minutes 50 seconds before the aircraft hit the water.

- There was an inconsistency (inconsistency) between the speeds shown on the left and those shown on the Integrated Standby Instrument System (ISIS). (The readings on the right display are not recorded.) This inconsistency lasted a little less than a minute. It led to the autopilot being switched off . Shortly thereafter, the co-pilot noted that the speed display had been lost and the flight control had switched to "Alternate Law". In this mode, the flight control software no longer prevents all maneuvers that the pilots may use to bring the aircraft outside of the flight range limit .

- After switching off the autopilot, the aircraft from the original rose FL . 350 (about 10,700 meters) to the height of 38,000 ft (11,600 m), then the was stall alarm (English: "stall warning") is triggered, and the plane plummeted.

- The control inputs of the controlling pilot (PF = “ Pilot Flying ”) consisted mainly of pulling the aircraft up (“Pitch-up”).

- The trimmable horizontal stabilizer (THS) changed from 3 to 13 degrees within one minute and remained in this position until the end of the flight.

- The descent took 3 minutes and 30 seconds; the aircraft was during this time in the coated (state stall English ( "stall")). The angle of attack increased and remained at over 35 degrees.

- The engines worked and always responded to the inputs of the crew.

- The last recorded values showed a pitch angle ( pitch ) of 16.2 degrees, a roll angle (bank angle) of 5.3 degrees to the left, a rate of descent of 10,912 ft / min (almost 200 km / h) and a ground speed of only 107 knots (also just under 200 km / h).

- Recordings ended at 2:14:28 am UTC .

- The report included a map with the route of the flight from Natal , a detailed view of the flight path for the last 6 minutes and a "3D view of the last 5 minutes of the flight".

- The analysis of the breaks in the force absorption of the rudder showed that more than 36 g had acted on this part of the aircraft.

Reports as of July 29, 2011

The "safety investigation" divides the flight into three phases:

- from the start of the recording by the Cockpit Voice Recorder until the autopilot is switched off

- from switching off the autopilot to triggering the stall warning

- from triggering the stall warning to the end of the flight

In contrast to the report of May 27, 2011, which only described and summarized the process, this report also describes processes that did not take place and are therefore to be understood as deficiencies:

- "Although the loss of the speed data was determined and announced, neither of the two co-pilots called the procedure 'Unreliable IAS' (Unreliable Indicated Airspeed )."

- "None of the pilots formally recognized the stall situation."

- "The aircraft's angle of attack was not displayed directly to the pilots."

The report mentions no other cause than the aircraft stalling during manual control and the resulting stall for the rapid loss of altitude before hitting the sea. It is expressly stated that the aircraft and engines behaved correctly according to the control inputs of the pilots.

Without a final assessment, the report lists significantly more pilot errors than aircraft errors. In some cases, pilot errors are even named twice: "None of the pilots referred to the stall warning" and directly behind it: "None of the pilots formally recognized the stall situation." However, the BEA expressly referred to the provisional nature of this report: "The investigation is currently being continued, to deepen the analysis and identify all the causes of the accident. These will be published in the final report of the BEA. "

Messages from the automatic radio data transmission system ACARS

| number | Time (event) |

Time of receipt |

aCars code | interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Before the actual events) |

22:45 | 22:45 | FAILURE LAV CONF | Malfunction toilet |

| 1 | 02:10 | 02:10:10 | WARNING AUTO FLT AP OFF | Warning autopilot off |

| 2 | 02:10 | 02:10:16 | WARNING AUTO FLT | Warning autopilot |

| 3 | 02:10 | 02:10:23 | WARNING F / CTL ALTN LAW | Warning Flight Control Alternate Law |

| 4th | 02:10 | 02:10:29 | WARNING FLAG ON CAPT PFD | Warning signs on the master's PFD (PFD = Primary Flight Display ) |

| 5 | 02:10 | 02:10:41 | WARNING FLAG ON F / O PFD | Warning signs on the first officer's PFD |

| 6th | 02:10 | 02:10:47 | WARNING AUTO FLT A / THR OFF | Warning Autopilot Autothrust off |

| 7th | 02:10 | 02:10:54 | WARNING NAV TCAS FAULT | Warning navigation TCAS error |

| 8th | 02:10 | 02:11:00 | WARNING FLAG ON CAPT PFD | Warning signs on the captain's PFD |

| 9 | 02:10 | 02:11:15 | WARNING FLAG ON F / O PFD | Warning signs on the first officer's PFD |

| 10 | 02:10 | 02:11:21 | WARNING F / CTL RUD TRV LIM FAULT | Warning flight control Ruderausschlagbegrenzer error ( rudder travel limiter fault ) |

| 11 | 02:10 | 02:11:27 | WARNING MAINTENANCE STATUS EFCS2 | Maintenance status warning |

| 12 | 02:10 | 02:11:42 | WARNING MAINTENANCE STATUS EFCS1 | Maintenance status warning |

| 13 | 02:10 | 02:11:49 | FAILURE EFCS1; PROBE-PITOT 1X2 / 2X3 / 1X3 | Failure of EFCS1 ( Electronic Flight Control System 2 ) and temporary failure of the pitot tube |

| 14th | 02:10 | 02:11:55 | FAILURE EFCS1 X2 (EFCS2X) | Failure of EFCS1 X2 |

| 15th | 02:11 | 02:12:10 | WARNING FLAG ON CAPT PFD FPV | Warning signs on the captain's PFD |

| 16 | 02:11 | 02:12:16 | WARNING FLAG ON F / O PFD FPV | Warning signs on the first officer's PFD |

| 17th | 02:12 | 02:12:51 | WARNING NAV ADR DISAGREE | Warning navigation ADR discrepancy (between the air data reference systems) |

| 18th | 02:11 | 02:13:08 | FAILURE ISIS 1 | ISIS 1 ( Integrated Standby Instrument ) error |

| 19th | 02:11 | 02:13:14 | FAILURE IR2 1, EFCS1X, IR1, IR3 | Error IR2 1, EFCS1X, IR1, IR3 |

| 20th | 02:13 | 02:13:45 | WARNING F / CTL PRIM 1 FAULT | Warning primary flight controller failure |

| 21st | 02:13 | 02:13:51 | WARNING F / CTL SEC 1 FAULT | Secondary flight control failure warning |

| 22nd | 02:14 | 02:14:14 | WARNING MAINTENANCE STATUS | Warning - maintenance status |

| 23 | 02:13 | 02:14:20 | FAILURE AFS | Failure of AFS ( Automatic Flight System ) |

| 24 | 02:14 | 02:14:26 | WARNING ADVISORY ( CABIN VERTICAL SPEED ) | Warning: Vertical cab speed |

Comparable events

- Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 6231 on a Boeing 727 on December 1, 1974

- Alas Nacionales Flight 301 with a Boeing 757 of Birgenair February 6, 1996

- Aeroperú flight 603 with a Boeing 757 on October 2, 1996

- Austral Líneas Aéreas flight 2553 on a Douglas DC-9 on October 10, 1997

- Air Algérie flight 5017 with a McDonnell Douglas MD-83 on July 24, 2014

- Saratov Airlines Flight 703 with an Antonov An-148 on February 11, 2018

media

The Canadian television program Mayday - Alarm im Cockpit shows a reconstruction of the accident and the course of the search work in the episode “Air France 447 missing” (Season 12, Episode 13).

In the US documentary series Mysteries of the Missing , German disappeared without a trace - Unsolved Mysteries , the plane crash in the episode Horrorflug (episode 8) is the subject of the program.

literature

- Bill Palmer: Understanding Air France 447 . 1st edition. William Palmer, 2013, ISBN 978-0-9897857-2-3 .

- Langewiesche, William . The Human Factor ( Archive ( September 18, 2014 memento on WebCite )). Vanity Fair . October 2014.

- Gérard Arnoux, Le Rio-Paris ne répond plus, AF447 "le crash qui n'aurait pas du arriver" , foreword, Frederic Fappani von Lothringen, July 2019, ISBN 978-2343180045

- Roger Rapoport, Shem Malmquist, Angle d'attaque - Causes et conséquences du crash Air France 447 (French Edition). July 2019, ISBN 978-2896265169

Web links

- AF447 website about the accident - Air France (German, English, Portuguese)

- Air France website on the accident in French and English

-

Vol AF 447 - Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la sécurité de l'aviation civile (French)

- Report on the investigation into the aircraft accident AF 447 on June 1, 2009 (PDF; 210 kB)

- Search operations in the sea (PDF; 566 kB)

- Final report ( PDF; 28 MB)

- Aircraft accident data and report in the Aviation Safety Network (English)

- Aviation Herald Reports - Full Factsheet

- William Langewiesche: Should Airplanes Be Flying Themselves? In: vanityfair.com. September 17, 2014, accessed June 10, 2017 .

Individual evidence

Final report

- Final report. (PDF) In: Safety Investigations. Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la sécurité de l'aviation civile , July 27, 2012, accessed on June 28, 2018 (English, final report, 223 pages).

- ↑ p. 1

- ↑ p. 31, "The last three checks [...] were performed on F-GZCP on December 27, 2008, February 21, 2009 and April 16, 2009."

- ↑ a b p. 24, "1.5.1 Flight crew"

- ↑ p. 46, "Cumulonimbus clusters that are characteristic of this zone were present, with a significant spatial heterogeneity and lifespan of a few hours."

- ↑ p. 200, "Temporary inconsistency between the airspeed measurements, likely following the obstruction of the Pitot probes by ice crystals that, in particular, caused the autopilot disconnection and the reconfiguration to alternate law;"

- ↑ p. 172, "When the autopilot disconnected, the roll angle increased in two seconds from 0 to +8.4 degrees without any inputs on the sidesticks."

- ↑ p. 173

Further individual evidence

- ↑ Data on the airline Air France flight 447 in the Aviation Safety Network (English)

- ↑ Air France F-GZCP ( English ) AirFleets.net. June 1, 2009. Accessed June 1, 2009.

- ^ Accidents + Incidents 2006. (txt) Jet Airliner Crashes Evaluation Center, accessed on February 23, 2013 (English).

- ↑ Eric Marsden: Air France flight 447 , Risk-engineering.org, August 24, 2017

- ↑ David Kaminski-Morrow: Stalled AF447 did not switch to abnormal attitude law. In: flightglobal.com. July 1, 2011, accessed February 23, 2013 .

- ↑ Safety Investigation Following the Accident on 1ST June 2009 to the Airbus A300-203, Flight AF 447. (pdf; 294 kB) bea.aero, July 5, 2012, accessed on February 23, 2013 (English).

- ↑ Final report, 3.1. Findings ; "In less than one minute after autopilot disconnection, the airplane exited its flight envelope following inappropriate pilot inputs."

- ↑ Weathergraphics.com AF447

- ↑ Crash: Air France A332 over Atlantic on Jun 1st 2009, aircraft entered high altitude stall and impacted ocean ( English ) The Aviation Herald . Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ↑ Aeronáutica 3 - Relatório the buscas do vôo 447 as Air France. In: defesa.gov.br. Archived from the original on September 20, 2009 ; Retrieved June 18, 2009 (Portuguese).

- ↑ Missing Air France machine: Brazilian Air Force discovers wreckage in the Atlantic - Disasters - Society - FAZ.NET . www.faz.net. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

- ↑ Marinha apoia buscas ao avião da Air France desaparecido. In: Notas à Imprensa. Marinha do Brasil , June 8, 2009, archived from the original on September 27, 2011 ; Retrieved June 28, 2018 (Portuguese, chronological compilation of the Brazilian Navy for the search from June 1, 2009 to June 8, 2009 with photos).

- ↑ Nuclear submarine is looking for flight recorder of the disaster Airbus www.spiegel.de. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- ↑ Search begins off Brazil's coast for 'disappeared' Air France flight ( English ) csmonitor.com. June 1, 2009. Accessed June 1, 2009.

- ↑ More bodies found from Air France crash ( English ) cnn.com. June 8, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ↑ [http://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/airfrancesuche102.html The difficult search for the flight recorders] (Link not available)

- ↑ Presentation Sea Search Operations Flight AF447 A330-203 F-GZCP of the BEA (PDF; 1.3 MB) Retrieved on September 10, 2010.

- ↑ http://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/airfrancmaschine132.html (link not available)

- ↑ Communication LES RECHERCHES EN MER from BEA (PDF; 28 kB) from July 2nd regarding the search

- ↑ RP Online: Special ships stop searching for Black Box ( Memento from July 12, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Third search for Air France flight 447 black boxes delayed (http) Airfrance447.com. March 11, 2010. Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved on March 13, 2010.

- ↑ Third search for Airbus wreck in the Atlantic started orf.at, March 26, 2010

- ^ Search for Air France Flight 447 Begun sciencedaily.com, March 26, 2010

- ↑ France wants to extend search for flight recorders Focus Online, April 28, 2010

- ↑ Crash point of Air France machine narrowed down . The time online. May 6, 2010. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Flightglobal.com

- ↑ lesechos.fr - Vol-Rio Paris: les recherches de l'épave vont reprendre ( Memento of the original from May 12, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ spiegel.de - diving robots are looking for wrecks again

- ^ Flight 447's Wreckage Found (http) Occupational Health & Safety. April 4, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ↑ Specifications REMUS 6000 - Autonomous underwater vehicle , Kongsberg Maritime.

- ↑ New search for crashed Air France Airbus. Autonomous submersible vehicles are to find wreckage of the plane that crashed in 2009

- ^ The hunt for Flight 447 (https) Kongsberg.com. June 2011. Archived from the original on December 23, 2019. Retrieved on December 23, 2019.

- ↑ WHOI-led team Locates Air France Wreckage , Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), April 4, 2011th

- ↑ AF 447: des débris de l'avion localisés en mer

- ↑ Death flight AF 447: wreckage of Air France machine located in the Atlantic

- ↑ Diving robot locates rear parts of the accident machine

- ↑ Information. (PDF) In: Safety Investigations. Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la sécurité de l'aviation civile , April 29, 2011, archived from the original on June 10, 2012 ; accessed on June 29, 2018 (English): "No lifting operations have yet been undertaken as priority has been given to the search for the flight recorders."

- ^ Message from the BEA on the recovered flight recorder (flight data recorder; FDR) dated May 1, 2011

- ^ Notice from the BEA on the salvaged voice recorder (Cockpit Voice Recorder; CVR) dated May 3, 2011

- ↑ 7 June 2011 briefing. (PDF) In: Safety Investigations. Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la sécurité de l'aviation civile , June 7, 2011, archived from the original on June 7, 2012 ; accessed on July 2, 2018 .

- ↑ Interim report. (PDF) In: Safety Investigations. Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la sécurité de l'aviation civile , July 2009, accessed on June 28, 2018 (English, first interim report, 128 pages).

- ↑ www.bea.aero cp090601e2.en (PDF; 9.9 MB) Second interim report , English translation

- ↑ a b Final Report. (PDF) In: Safety Investigations. Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la sécurité de l'aviation civile , July 27, 2012, accessed on June 28, 2018 (English, final report, 223 pages).

- ↑ Official transcript of the Cockpit Voice Recorder (French)

- ^ Jean Pierre Otelli, Erreurs de pilotage , Altipresse, 2011

- ↑ Chesley B. Sullenberger's analysis of the accident situation Air France 447: Final report on what brought airliner down . In: YouTube (video, English)

- ↑ For a complete list of nations, see Air France Press Release No. 5 ( English and Portuguese ) June 1, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ↑ Passengers from 32 nations on board ( German ) Hamburger Abendblatt. June 2, 2009. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

- ↑ Number of German victims increases from 26 to 28 SZ, June 4, 2009

- ↑ Brazil stops salvage work on the high seas Spiegel Online, June 27, 2009

- ↑ www.spiegel.de

- ↑ a b rtvutrecht.nl Zeisterse in verdwenen Air France vlucht

- ↑ En el avión desaparecido de Air France iba una azafata argentina

- ↑ Flygplan försvann över atlases

- ↑ The Last Resital in Rio de Janerio ( Memento of 19 July 2010 at the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Lista de pasajeros

- ↑ Final words from flight AF447 .

- ^ First compensation judgment in Brazil, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, March 12, 2010

- ^ Compensation judgment in France NZZ, September 29, 2010

- ↑ Investigative judges set the case for Air France crash with 228 dead . In: nzz.ch, September 5, 2019 (accessed September 5, 2019).

- ↑ Booking query on airfrance.de and flightradar24.com, November 2013.

- ↑ New safety recommendations . (PDF; 68 kB) BEA, July 29, 2011, p. 1 , accessed on July 30, 2011 (document without date and without express reference to flight 447): “The analysis of the flight sequence based on the evaluation of the flight recorder made it possible to formulate ten new safety recommendations. "

- ↑ www.bea.aero point.enquete.af447.27mai2011.fr (PDF; 1.5 MB) Report of May 27, 2011, French original

- ↑ www.bea.aero point.enquete.af447.27mai2011.de (PDF; 1.1 MB) Report of May 27, 2011, German translation

- ↑ Fly by wire explained by an Airbus pilot . In: plasticpilot.net

- ↑ a b c Safety investigation into the accident involving the Airbus A330-203, flight AF 447, from June 1, 2009. (PDF; 98 kB) BEA, July 29, 2011, p. 4 , accessed on July 30, 2011 .

- ^ Air France Flight 447: Unofficial ACARS. flight.org, June 7, 2009, archived from the original on June 25, 2009 ; accessed on June 28, 2018 (English): "It has to be stressed that the the data is very unofficial so shouldn't be relied upon as correct, legitimate or correct."

- ↑ AF447 - Interpretazione dei 24 messaggi ACARS . In: wordpress.com (ital.)

- ↑ [1]

Coordinates: 3 ° 3 '57 " N , 30 ° 33' 42" W.