Volga Ural Tatars

Volga-Ural Tatars (Tatar: Идел-Урал татарлары ) is a collective name used by the Tatar ethnic groups in the Volga and Ural regions . In Europe , the name Volga Tatars is particularly common.

In a narrower sense, this term mainly includes the Tatar residents of the Russian autonomous republics of Bashkortostan and Tatarstan . The latter in particular are subsumed under the term “Volga Tatars”, meaning that Kazan Tatars or Qazanlıq are meant. In Tatarstan they form the titular nation .

The Volga-Ural Tatars see themselves today as direct heirs of both the former Golden Horde and the Volga Bulgarians . The Chuvashes and Bashkirs , who also speak Turkic, are not counted among the Volga-Ural Tatars .

structure

Today the following Tatar population groups are counted among the Volga-Ural Tatars:

- Kazan Tatars (Qazan Tatarları)

- Qasim Tatars or Kassimower Tatars (Qasıym Tatarları)

- Mishar Tatars or Mishars (Tat. Mişärlär; Russian Мишари), outdated Meschcherjäken

- Teptjaren (Tat. Tiptärlär; Russian Тептяри)

- Nagaibaken (Nağaybäklär)

Qasim Tatars or Kassimower Tatars

→ Main article: Kassimov

The Kasimow Tatars go back to the Khanate of Kassimow (tat. Qasıym xanlığı; Russian Каси́мовское ха́нство) in what is now Ryazan Oblast .

Teptjars

→ Main article: Teptjars

The Tatar- speaking Teptjars (Tiptärlär) are historically a military class in Bashkortostan linked to land ownership , similar to the Bashkirs and Cossacks . They are said to have had a strong sense of class, but ethnically, at least in the initial phase, they were very heterogeneous. Their classification as an ethnic group is therefore controversial. For example, the 1st Tepyar Regiment, which was set up in 1798 and took part in the Napoleonic War , consisted of Udmurts , Bashkirs, Chuvashes , Tatars, Mari and Mordvins . At the end of the 19th century there were around 126,000 Teptjars in the Orenburg and Ufa Governments . The number of Teptjars in Bashkortostan was recorded as a separate ethnic group for the last time in 1926. Their number was given as only 23,290 people.

Some of the Teptyars were and are also attributed to the Bashkirs.

Nagai hooks

→ Main article: Nagai hooks

The Nagaibaken are a Christian Tatar ethnic group in the Chelyabinsk Oblast around the village of Ferschampenuas .

Special case Astrakhan Tatars

The Astrakhan Tatars (AstraxanTatarları) belong to the Volga-Ural Tatars only from a historical perspective. Today these are generally regarded as an independent Tatar group of the Volga-Ural region, which has more in common with the Nogaiians than with the other Tatars. However, the Astrakhan Tatars are occasionally counted among the Volga Ural Tatars and listed as their 6th subgroup.

The Astrakhan Tatars, along with the Volga and Crimean Tatars, were the heirs of the Golden Horde , as their Khanate formed one of the four successor empires of the former Mongolian sub-empire.

Culture and customs

Festivals

Sabantui is a summer festival which is also celebrated by the Bashkirs and Chuvashes. Originally the festival was celebrated by farmers before sowing, nowadays it is a national holiday and is also celebrated in cities . Local costumes are worn during the Sabantui . The main elements of the festivities are the Tatar Kurash wrestling , horse racing , column climbing and other strength and skill competitions.

Food

Above all, various dumpling specialties belong to the traditional cuisine of the Volga-Ural Tatars, such as Etschpotschmak and Kystybyj . As with the neighboring peoples of the Kumys , traditional drinks include a slightly alcoholic drink made from fermented mare's milk.

The dessert of the Volga-Ural Tatars Tschak-Tschak is known throughout Russia . Tschak-Tschak is made from a soft dough made from wheat flour and raw eggs, which are formed into short, thin sticks. These are deep-fried and then poured over with a hot mass based on honey . Tschak-Tschak is served as a dessert with coffee or tea or generally as a tea side dish.

Another traditional dish is gubadija (bashk. Ғөбәҙиә, tat. Гөбəдия) , which is also widespread among the Bashkirs . It is a closed, round, multi-layer cake filled with rice and raisins. The traditional variant is sweet and served with tea, but there are several variations on the recipe, including meat. The gubadija is served on festive occasions and is part of the wedding dinner. It has a ritual function similar to that of wedding bread , Karawai , among Slavic peoples.

dress

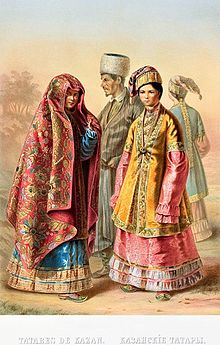

The clothing complex of the Volga Tatars, which arose at the end of the 19th century, had a significant impact on the formation of the uniform modern type of national costume. Oriental traditions and Islam also had a strong influence on the Tatar costume.

Nowadays this national costume is mainly used as a folkloric prop. The basis of the costume consists of the Kulmek (shirt dress) and trousers, as well as Beschmets, Chekmen and Cossacks (all types of caftan ). As outerwear has often Chalat worn. There was also a choba, light, unlined outerwear. It was usually sewn from linen or hemp fabrics that ended just below the knees.

Vests were common among girls and women.

The tjubetjeka (Russian тюбете́йка, тат. Түбәтәй) had a special place in men's headgear . In the Tatars of the Volga-Ural region, the Tyubetejka is classically round and the top is flat. The tjubetjeka is the traditional headgear of the Turkic peoples of Eurasia. It is worn in different variations by Kazakhs , Uzbeks , Uyghurs, Turkmens, but also by the Indo-European Tajiks and Pamirs. The kalfak (tat. Калфак) was the most important headgear for women. It is a kind of slouch hat. When leaving the house in the cold season, the men wear a tjubetjeika and the women wear a hemispherical fur or a quilted hat with a fur tip over the headscarf.

Part of the national intelligentsia in the late 19th to early 20th centuries began to wear the fez, following the fashion of the time imitating Turkish traditions . It was common practice among Muslim clergy to wear turbans, including among Tatars.

The tjubetejka and the tying of the headscarf according to the Tatar style ("по-татарски") have only kept a few of the traditional clothing . These items of clothing are found especially among the older rural population.

Dialects

The Tatar language of the Volga-Ural Tatars is divided into three dialects. The western dialect spoken by the Mishar Tatar sub-ethnic group, the middle dialect of the Kazan Tatars and the dialect of the Qasim Tatars.

Geographical distribution in Russia

Volga Ural Tatars in Tatarstan

The titular nation of the Volga-Ural Tatars, which gives the Republic of Tatarstan its name, makes up the majority population with 53 percent. At the last census in 2010, there were 2,012,571 Tatars in Tatarstan.

Volga Ural Tatars in Bashkortostan

In Bashkortostan , the Tatars are the third largest ethnic group after the Russians and Bashkirs . In 2010 the population of Bashkiria was 1,009,295 Tatars. They make up 25 percent of the population. The majority of the Tatars of Bashkiria can be traced back to the sub-ethnic groups of the Teptyars and Mishars.

Tatar minorities outside Russia

Tatar ethnic groups, which can be directly derived from the Volga-Ural Tatars, also live in the Eastern and Northern European countries of Poland , Ukraine , Belarus , Finland and Sweden . But descendants of the Volga-Ural Tatars can also be found in Kazakhstan , Uzbekistan and among the Tatars of China .

literature

- Erhard Stölting : A world power breaks up - nationalities and religions of the USSR , Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 1990, pages 143-155, ISBN 3-8218-1136-6 .

- Harald Haarmann : Small encyclopedia of peoples: from Aborigines to Zapotecs , Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-51100-7 (= Becksche series , volume 1593, pages 318ff “Tatars” ).

- Detlev Wahl: Lexicon of the peoples of Europe and the Caucasus . Meridian, Rostock 1999, ISBN 3-934121-00-4 .

- JW Bromlej: народы мира - историко-этнографический справочник (Peoples of the World - Historical-Ethnographic Words / Handbook) , pages 433f. Moscow 1988.

- RK Urazmanova, SV Cheshko, (Sergeĭ Viktorovich), Уразманова, Р. К., Чешко, С. В. (Сергей Викторович): Tatary . Moscow, ISBN 5-02-008724-6 .

See also

- Islam in Russia

- Islam in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus

- Islam in Finland and Finland Tatars

- Islam in Estonia

Individual evidence

- ↑ Noack, Christian .: Muslim nationalism in the Russian Empire: nation-building and national movement among Tatars and Bashkirs: 1861-1917 . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-515-07690-5 .

- ↑ Dimitrieva, Marina., Karl, Lars .: The year 1813, East Central Europe and Leipzig: The Battle of Nations as a (trans) national place of memory . Cologne, ISBN 978-3-412-50467-0 .

- ↑ Heartburn - Uralit . In: Herrmann Julius Meyer (Ed.): Meyers Konversationslexikon . 4th edition. tape 15 . Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig and Vienna, pp. 592 .

- ↑ Всесоюзная перепись населения 1926 года. Национальный состав населения по регионам РСФСР. In: http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_nac_26.php?reg=772 . Демоскоп Weekly, accessed February 15, 2020 (Russian).

- ↑ a b R. K. Urazmanova, SV Cheshko, (Sergeĭ Viktorovich), Уразманова, Р. К., Чешко, С. В. (Сергей Викторович): Tatary . Moscow, ISBN 5-02-008724-6 .

- ↑ The dessert Tschak-Tschak. Retrieved May 30, 2020 .

- ↑ Губадия. Retrieved May 30, 2020 .

- ↑ Ателье "LuiZa" - Татарская народная одежда. Retrieved May 30, 2020 .

- ↑ Ателье "LuiZa" - Татарская народная одежда. Retrieved May 30, 2020 .

- ↑ Data from the 2010 Russian Census. Federal State Statistics Service of the Russian Federation, accessed February 14, 2020 (in Russian).

- ↑ Statistics of the 2010 census. In: https://www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/perepis2010/croc/perepis_itogi1612.htm . Rosstat, accessed February 14, 2020 (Russian).