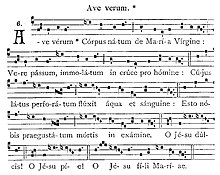

Ave verum

Ave verum is a late medieval rhyme prayer in Latin, named after its incipit . It probably originated in the 13th century; the author is unknown.

Liturgical location

The text has its seat in life in the adoration of the Eucharist in Holy Mass . The believers greet the true body of the Savior, who is believed to be real present during the walk in the forms of bread and wine , and venerate the redeeming suffering of Christ . The prayer leads to the request to receive communion at the hour of death as a foretaste of heaven.

The prayer never belonged to the official texts of the Ordo missae , but had the character of a private prayer . It was spoken quietly by the believers in the Middle Ages after the elevation of the converted gifts, while the priest continued with the Canon Missae . Late medieval missals recommended it - in addition to other prayers such as O salutaris hostia or Anima Christi - as a silent preparatory prayer for the faithful before receiving communion, but also for the priest pro animi desiderio ("for the desire of the soul") in addition to his official prayers . From the end of the 15th century until modern times, the ave verum was sung for elevation. This practice spread from France and was promoted by the Cistercians .

text

Liturgical version

Ave verum Corpus natum

de Maria Virgine

Vere passum, immolatum

in cruce pro homine:

Cujus latus perforatum

fluxit aqua et sanguine:

Esto nobis praegustatum

mortis in examine.

O Jesus dulcis!

O Jesus pie!

O Jesu fili Mariae.

Version by Mozart

Ave, ave, verum corpus,

natum de Maria virgine,

vere passum immolatum

in cruce pro homine,

cuius latus perforatum

unda fluxit et sanguine

esto nobis praegustatum

in mortis examine,

in mortis examine!

translation

Greetings, true body,

born of Mary the Virgin,

who truly suffered and was sacrificed

on the cross for man;

whose pierced side

flowed with water and blood:

Be a foretaste for us

in the trial of death!

Transfers

Rhythmical

Greetings to the true body, born

of Mary, pure woman.

Really tortured, sacrificed

on the cross for human health .

Pricked with the lance,

water flowed out and blood.

Shall we have tasted

when death will test us.

anonymous

Rhymed

Greetings to us, true body,

whom Mary bore us;

who atoned for us on the cross, who was

the sacrifice of atonement!

Blood and water flow from you

because your heart was pierced.

Give us that we enjoy you

in the last danger of death!

O gracious Jesus,

oh gentle Jesus,

oh Jesus, you Son of God and the Virgin Mary.

(after Heinrich Bone )

Adapted

The following text can be sung slightly adapted to Mozart's setting.

Greetings to you, Body of the Lord, born

of Mary's pure womb!

To bring home what was lost,

you bore the cross and deathless.

From the spear-pierced side

, blood and water flowed red.

Be us a foretaste in the struggle,

heavenly power in dire straits!

Medieval translations into the vernacular

In addition to the above translations , the rhyme prayer was translated into the vernacular as early as the Middle Ages . The manuscript census provides an overview of these text accesses .

Text history

The Latin rhyming prayer has been incorporated into many collections of religious texts and songs since about 1300. In comparison, the copies show many deviations, some accidentally, some as an intentional addition or redesign.

The oldest known record, from the 13th century, was found in a manuscript in the Martinus Library in Mainz (still without the O invocations at the end). Another text from Genoa can be dated to around 1294. Another copy names Innocent IV , Pope 1243 to 1254, born in 1195 in Genoa as the author . Subject , vocabulary, handling of meter and Latin style do not rule out an attribution to St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274).

As far as one can reconstruct this from the many variants, the prayer originally seems to have had the following wording:

Ave verum corpus natum

ex Maria virgine,

vere passum, immolatum

in cruce pro homine,

cuius latus perforatum

vero fluxit sanguine,

esto nobis praegustatum

mortis in examine.

o dulcis, o pie,

o fili Mariae,

in excelsis.

It is noticeable that forms of the vocabulary verum 'real, true, really' are used repeatedly, apparently to show that the body is not meant in a figurative sense, but rather designates the real existing, flesh and blood body of the person Jesus . Against vero in v. 6, however, speaks the more frequently encountered, evangelical reading fluxit unda_et sanguine ( Joh 19,34 EU : exivit sanguis et aqua; cf. 1 Joh 5,6 EU : hic est qui venit per aquam et sanguinem Iesus Christ ), here through the palaeographic maxim difficilior lectio propior supported.

Variants are known to almost a third of the words, including additions partly rhythmically or rhymed, partly in prose, and a second stanza on the same rhyme scheme. The sequences Ave panis angelorum and Ave virgo gloriosa also follow this rhyme scheme .

Some records indicate that the believing Christian can earn 40 days, 300 days, or 3 years indulgence by saying the prayer or his opening words at the elevation or at personal devotion in front of the tabernacle .

Compositions

According to the sources, the text was sung a lot in the Middle Ages, so it had a melody even then.

Many composers set the text to music, including Guillaume Du Fay , Josquin Desprez , Francisco de Peñalosa , Orlando di Lasso , William Byrd , Peter Philips , Richard Dering , Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart , Franz Liszt , Charles Gounod , Camille Saint-Saëns , Edward Elgar , Francis Poulenc , Colin Mawby , Alwin Michael Schronen , Karl Jenkins , Imant Raminsh and György Orbán .

The best known and most frequently performed setting today is the Ave verum corpus ( KV 618) by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart . Its version gave the old sequence widespread use outside of church events. In accordance with Christian doctrine, the text considers the physical presence of the Savior in the Eucharist . The last lines refer to the example of the dying Redeemer for his believing followers. Mozart left out the last verse of the hymn with the threefold call to Jesus for unknown reasons. Often the bereaved choose his contemplative, relaxing and ultimately comforting setting as musical accompaniment for funeral ceremonies.

The composition was intended for the Corpus Christi festival in Baden near Vienna in 1791 , where Mozart's wife Constanze was preparing for her sixth childbirth in the ninth year of marriage. She lived with Anton Stoll, the choirmaster of the Baden church choir, who accepted the motet as a gift. A year later, Mozart's student Franz Xaver Süßmayr also composed an Ave verum corpus for Anton Stoll.

literature

- Clemens Blume and HM Bannister: Liturgical Prose of the Transitional Style and the Second Epoch. Reisland, Leipzig 1915, p. 257 f.

- Franz Joseph Mone : Latin hymns of the Middle Ages. Scientia, Aalen 1964 (= Freiburg im Breisgau, 1853), p. 280 f. ( Scan in google book search)

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Josef Andreas Jungmann : Missarum Sollemnia. A genetic explanation of the Roman mass. 5th edition. Volume 2. Herder, Vienna / Freiburg / Basel 1962, p. 431, note 16.

- ^ Andreas Heinz : Ave verum . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 1 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1993, Sp. 1307 .

- ^ Liber Usualis . Parisii, Tornaci, Romae 1954, p. 1856.

- ↑ Prayer and hymn book for the Archdiocese of Cologne. Verlag JB Bachem, Cologne 1949, No. L 229, p. 878 f.

- ↑ Text version of Peter Gerloff's on Mozart's movement in the sheet music (PDF; 34 kB). In: haben-singen.de, July 3, 2006, accessed on June 15, 2019.

- ↑ Complete directory of authors / works. 'Ave verum corpus natum', German overview of the German translations of the rhyme prayer. In: Manuscript Census , accessed on June 15, 2019.

- ^ Press release of the Diocese of Mainz: The prayer "Ave verum" is older than previously assumed. Fragment discovered in Martinus Library. In: bistummainz.de, May 14, 2019, accessed on May 15, 2019.

- ^ Franz Joseph Mone: Latin hymns of the Middle Ages. Scientia, Aalen 1964 (= Freiburg im Breisgau, 1853), p. 280 f.

- ^ The "Ave verum corpus". Church choir Baden St. Stephan, accessed on March 10, 2016 (information on the work, facsimile of the autograph, sheet music, audio recording). .