Beast of Gévaudan

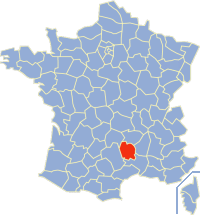

Bestie des Gévaudan ( French Bête du Gévaudan ) is the name of a predator whose attacks in the years 1764 to 1767 in Gévaudan ( southern France ) and adjacent areas killed around 100 children, young people and women. The Gévaudan was a sparsely populated historical province in the Massif Central ; its borders largely corresponded to those of today's Lozère department . Some historians believe that several animals were involved in the attacks.

The historical events

In the traditions of events, verifiable facts are mixed with myths . The following contemporary documents exist as sources:

- the parish registers of all affected parishes, in which the names of victims are recorded

- Correspondence between the police officers of the Auvergne in Clermont and the Languedoc in Montpellier with their local representatives in Gévaudan

- numerous reports of the driven hunts ordered by the king

- contemporary newspaper articles and drawings

The victims

The number of known deaths varies from 78 to 99, depending on the source, and those of injured from 50 to 80. The youngest victim was three years old, the oldest probably 68 years old. Around every fourth fatality was older than 16 years; in this age group only women were killed. The first officially registered attack took place on June 30, 1764: The body of the 14-year-old shepherdess Jeanne Boulet from the parish of Saint-Étienne-de-Lugdarès in Haut- Vivarais , across the border of the Gévaudan, was found torn the following day. However, it is very likely that an attack on a shepherdess in the spring of 1764 in Saint-Flour-de-Mercoire, in the east of Gévaudan, which cannot be precisely dated, can be assigned to the beast.

Most of the victims were attacked in pastures or fields, others in front of their homes, in gardens, on roads, in a ravine, on a river island or in wooded land. Some of the beast's attacks happened in quick succession in the same area. On the other hand, the beast often changed its attack locations over distances of several kilometers or shifted its activity to a new attack area. Many victims were abducted, some alive. Some of the attacked suffered bite wounds and injuries from claws. 15 victims were beheaded and some heads were abducted.

Many of the attacked managed to escape injured or unharmed. Often helpers rushed over, often armed with lances or agricultural implements, and drove away the beast. In some cases children or adolescents defended attacked siblings or comrades, always at the risk of their lives. The twelve-year-old Jacques André Portefaix became famous, who was attacked on January 12, 1765 together with six other children in the Margeride mountains . The beast seized eight-year-old Jean Veyrier from this group of little shepherds who wore metal-bladed lances and dragged him into a swamp. Jacques prevailed over his comrades by urging them not to abandon Jean, and he was the first to pursue the beast. The beast was restricted in its freedom of movement in the swamp, it held Jean with one paw. While the children stabbed the beast with their lances, Jean escaped with an arm injury.

For the heroic defense of her children in an attack on March 13, 1765 in the hill country of the municipality of Saint-Alban , the approximately 35-year-old Jeanne Jouve was honored throughout France. Jeanne fought in her garden against the beast who alternately grabbed her six-year-old son and her ten-year-old daughter with her teeth. Jeanne succeeded again and again in snatching the children from the beast. Jeanne tried to prevent the beast from escaping with her son, among other things, by repeatedly jumping on the beast's back, but repeatedly being shaken off. Eventually the beast and the child escaped over a wall. Jeanne's 13-year-old son became aware of the drama and pursued the beast with the family's herding dog. When the dog attacked the beast, she let go of the severely injured child; it died six days later. Both Jacques Portefaix and his comrades as well as Jeanne Jouve were taken over by King Louis XV. honored for their bravery and received a cash award.

the beast

A wealth of details has been passed down about the size, appearance and behavior of the beast. The size of the animal has often been compared to that of a one year old bovine ; a kick seal was 16.2 centimeters long. The beast's body was bulkier in front than behind, the top of the head was flat. The animal had reddish fur on the top and whitish fur on the underside, spots on the flanks and a dark stripe along the spine. The fur on the front body was long, the beast wore a mop of hair on the back of its head and neck, and the end of its tail was noticeably thick.

The enormous power of the beast is proven, among other things, by the fact that it also abducted adult humans; In addition, a jump of nine meters width was reconstructed on the basis of step seals. The beast hunted in a region whose impermeable subsoil is characterized by rocks of volcanic origin. On this geological basis, a diverse landscape with a mosaic of hills, volcanic cones, grasslands, forests, bodies of water, swamps and rock formations developed in Gévaudan, which provided cover for the beast in many places and made it difficult to track. The beast stayed there primarily in the open landscape, where it stalked victims and, for example, sneaked up to them pressed against the ground. The strangling of victims has been shown to be a killing strategy. In some cases, the beast devoured large parts of a human victim's body in a matter of minutes; in two cases she had completely cleaned of soft tissue from the skulls of her victims found a few days after the attack. The calls of the beast have been described, among other things, as a terrible bark.

Wolves in Gévaudan

Around the middle of the 18th century there was still a relatively high wolf density in the French Massif Central compared to later centuries. Wolves were well known to the rural population there. Occasionally rabid and rabies-free wolves attacked people. On April 9, 1767, a nine-year-old child was killed by a wolf near Fraissinet (municipality of Saint-Privat-du-Fau) and another child was seriously injured. The species belonging to the attacking animal is beyond question. Wolves were persecuted intensely in Gévaudan; for example, from 1766 to 1767, 99 wolves were killed within twelve months. Some contemporary authors such as Jean-Marc Moriceau and Giovanni Todaro assume that all predatory attacks in the years 1764–67 were attributable to wolves or mixed- blood wolves .

People involved

- Gabriel Florent de Choiseul Beaupré , Bishop of Mende

- the king's wolf hunters:

- Mr. Denneval, father and son

- François Antoine, royal crossbow bearer, great wolf hunter of royalty, knight of the Ordre royal et militaire de Saint-Louis

- his son Antoine von Beauterne

- the natural scientist Comte (Graf) de Buffon , curator of the Botanical Garden of Paris, member of the institute ( Académie française )

- the Marquis Jean-Joseph d'Apcher

- Jean Chastel , called "The Mask", and his sons Pierre and Antoine Chastel

The Bishop of Mende

The Bishop of Mende ( hostile to the Enlightenment ), Gabriel-Florent de Choiseul Beaupré, saw the beast as a scourge of God. In a pastoral letter that he had read in his diocese , he proclaimed that God's wrath had come upon people:

“The righteousness of God, says St. Augustine , cannot accept that innocence is unhappy. The punishment that he imposes always presupposes the wrongdoing of the person who incurred it. From this principle it will be easy for you to understand that your misfortune can only have arisen from your sins. "

The bishop quotes from the book of Deuteronomy (32.24 EÜ ):

"I let go of the predators' teeth on them."

as well as from Leviticus (26.21 EÜ ):

"If you ... don't want to listen to me, I'll give you more blows."

The hunters

Because of the uprising of the camisards , the king had all firearms and long cut and stabbing weapons withdrawn. The farmers in Gévaudan were therefore initially reliant on their self-made lances, knives, axes and forks for their protection. In September 1764, however, the residents of the canton of Langogne received temporary permission to carry firearms in order to be able to take part in the hunt for the beast. In the same month, King Louis XV. deploy a 57-man dragoon unit under the command of Capitaine Duhamel in the region with the mission to track down and kill the beast.

Three groups in particular took part in the hunts:

- From September 1764 to April 1765, Capitaine Duhamel and his dragoons were stationed in Saint-Chély-d'Apcher .

- In February 1765 the famous Norman wolf hunters d 'Enneval, father and son, reached Malzieu ; d'Enneval Sr. boasted of having killed over 1200 wolves. His six best dogs trained to hunt wolves were sent to him by carriage.

- From June 1765, François Antoine, the royal crossbow bearer and the king's second hunter, stayed at Besset Castle. Antoine was accompanied by 14 shooters and brought five hunting dogs with him.

The largest hunt in February 1765 involved over 20,000 hunters, soldiers and drivers. The beast was found, but escaped by crossing the Truyère River. The beast avoided carcasses laid out as poison bait , but numerous other animals such as wolves and shepherd dogs died.

Bounty on the beast

Eventually over 9,000 livres were set aside for the capture of the beast. The king contributed 6,000 and the bishop 1,000. The reward was substantial for the time, about the value of 100 horses.

As a "beast" killed wolves

In Gévaudan, numerous wolves were killed between 1764 and 1767; at least five of them were suspected to have been the beast. Two hunted animals became particularly well known:

On September 20, 1765, François Antoine and his nephew Rinchard shot a noticeably large wolf in the forest near Saint-Julien-des-Chazes. Witnesses to beast attacks stated that this wolf was the beast. According to Jay M. Smith, however, the Witnesses were under psychological pressure and had little choice but to identify the wolf as a beast. The wolf was exhibited as a preparation in an anteroom of the royal palace in Versailles. Since there were doubts as to whether the wolf was actually the beast, Antoine only received the reward on the beast after a few weeks.

However, the beast continued its attacks: On December 2, 1765, two children were again attacked on the southern slope of the Mouchet mountain in the Margeride. But since the beast was believed to have been killed and the reward had already been paid, the authorities initially ignored this attack and others who were now concentrating on the Margeride.

On the morning of June 19, 1767, Jean Chastel killed a male predator in the Teynazére forest in the Margeride mountains, the description of which remains a mystery to this day. On June 26th, a she-wolf was also shot, which apparently had been on the road on June 19th with the animal that Chastel had killed.

The Marin Report

Maître Roch Etienne Marin, royal notary from Langeac , drew up a report on the animal killed on June 19th in Besques Castle on June 20th, 1767 . This report Marin (bundle F 10-476, collection: Agriculture: Destruction of harmful animals) was rediscovered in the Archives Nationales in 1958 . According to the report, the animal had a head body length of 127 centimeters, a 22 centimeter tail, a shoulder height of 77 centimeters, a shoulder width of 30 centimeters and a mouth span of 19 centimeters. Maître Marin also noted, among other things:

“Monsieur le Marquis had this animal carried to his castle in Besques, parish Charraix . So we decided to go there to examine it. […] Monsieur le Marquis had us show this animal. It seemed to be a wolf, but a very unusual one and very different from the other wolves in this area. More than 300 people from the area have testified to this. Some hunters and many professionals have testified that this animal only resembles the wolf by its tail and rump. His head is monstrous. […] His neck is covered by a very thick fur of a reddish gray, with a few black stripes; it has a large white spot in the shape of a heart on its chest. The paws are equipped with four claws that are much more powerful than those of other wolves; the front legs in particular are very thick and the color of the roebuck, a color that experts have never seen in a wolf. "

This is followed by a list of further body measurements and a precise description of the teeth, as well as a list of 26 names of people who had seen the beast and who testified that it was the beast sought. However, descriptions of the beast that were noted before the animal was killed contradict the description of the dead animal. There is evidence that the Marin Report attempted to portray a normal wolf as a beast. For example, the dimensions of the supposedly monstrous head correspond to the dimensions of a normal wolf's head, and the description of the fur colors does not suggest an unusually colored wolf. In addition, the slain male was traveling with a she-wolf when Chastel shot him. In the Gévaudan, the descriptions of other wolves were also adapted to match descriptions of the beast.

Whereabouts of the animal killed by Chastel

According to a widespread tradition, which, according to Jay M. Smith, belongs more to the realm of fable ("surely closer to fable than to reality"), Chastel carted the inadequately preserved animal to Versailles in August with a servant of the Marquis d'Apcher . However, the king is said to have ordered the decaying carcass to be buried immediately. According to a publication published around 1809 and rediscovered in an archive in Mende, it was not Chastel but the domestic servant Gibert who transported the animal to Paris on the instructions of the Marquis d'Apcher together with a companion hired for the trip. According to Gibert, the Comte de Buffon, the most renowned naturalist in France at the time, carried out a careful examination of the carcass, which had been eaten by "worms" and depilated by decomposition, on the king's orders on the grounds of a hotel (today located on Rue de Seine). Buffon came to the conclusion that it was “just a big wolf” (“après un examen sérieux, jugea que ce n'était qu'un gros loup”). Then Gibert buried the carcass.

Species hypotheses

There are various hypotheses that doubt that the beast was supposed to have been a wolf: In the television documentaries The Real Wolfman and The Secret of the Werewolves , the thesis was put forward that it could be due to the size, appearance and coat color of the hunted animal traded a spotted hyena (less likely a striped hyena or a black horned hyena ) brought back from Africa. This assumption was made as early as 1764: “This animal is a great predator from Africa, in the Kingdom of Egypt, known under the name of the hyena, which was brought to the animal garden of the Duke of Savoy at Turin, and from which it escaped. “One of the arguments against this is that the animal that Chastel killed allegedly had a different number of teeth. Another hypothesis is that an African wild dog brought from Africa could have caused the raids. The assumption that the beast's attacks were carried out by rabid wolves is incorrect, as it was a question of targeted attacks and quick subsequent concealment, both of which speak against animals with rabies. National Geographic published a hypothesis that the beast's descriptions of size, appearance, behavior, vocalizations, physical strength, and footprints suggest an escaped subadult male lion . At the end of the 18th century menageries came into fashion with the French aristocracy, so that it could very well be an escaped lion - but a lion in wolf's clothing, since most people assigned it the shape of a wolf.

Ahistorical attempts at explanation

Since the beginning of the 20th century, attempts at explanations have been published that portray a person either as an immediate attacker or as a planner and conductor of the predatory attacks. What these attempts at explanation have in common is that they are not compatible with the overall picture of historical traditions. The authors in question were inspired, among other things, by reports on serial killers or by fictional literature, such as a novel by Abel Chevalley published in 1936. History professor Jay M. Smith gives an overview of these ahistorical attempts at explanation, a selection of which is presented here.

The French doctor Paul Puech published a treatise in 1912 in which he saw the beast as a psychotic serial killer; he justified this by stating that the victims were women and children, that corpses were beheaded and mutilated senselessly. In 1976, Gérard Ménatory presented a motif that was later taken up by other authors, according to which the beast was a trained predator (according to Ménatory a hyena) that attacked humans on the orders of his trainer. Michel Louis described the beast in 1992, like Hervé Boyac in 2004, as a hybrid of wolf and domestic dog, trained to kill and equipped with a kind of vest to protect against firearms and stabbing weapons. The identity of the alleged perpetrator changes depending on the publication: In the ZDF documentary Das Monster von Gévaudan (2003), a mixture of facts, fiction and a distorted representation of historical events, Jean Chastel, for example, was considered a suspect. The amalgamation of fantastic elements with traditional history, which was widespread into the 21st century, meant that serious historical research largely avoided the subject of the “Beast of Gévaudan”.

Further series of attacks in France

In historic France there were a number of other series of predatory attacks; The series in Gévaudan has a special position primarily because it has been handed down with a wealth of facts through a large number of contemporary documents. Series of attacks at the time of Louis XIV , especially a series in the Limousin from 1698 to 1700, show clear parallels to the events in Gévaudan. The events in the Limousin are similar to those in Gévaudan, both in terms of the appearance and behavior of the attacking animal and in terms of the landscape and size of the attack area. As in the case of the Gévaudan attacks, the attackers' species affiliation is controversial: Wolf attacks and attacks by big cats are discussed , which, like other large carnivores, were displayed in menageries and at fairs and chased against each other in exhibition fights .

Film adaptations

movie theater

The story of the Beast of Gévaudan was filmed as the Pact of the Wolves (French Le Pacte des loups ) with Samuel Le Bihan , Monica Bellucci and Vincent Cassel in the leading roles.

In the spring of 2000, the French director Christophe Gans began shooting this large-scale film (30 million euros) in Esparros in the French Hautes-Pyrénées department , which is based on the events in Gévaudan. Gans, the co-author of the script, had studied the old documents intensively. In his film, however, he transforms the beast of Gévaudan into an animal imported from Africa, which its owner trained to kill people and which is made invulnerable by armor.

In the frame story, the old Marquis d'Apcher writes on his memoirs, which then lead over to the actual plot of the film, which is based on the actual events. One of the fictional characters in the film is the Indian Mani (played by Mark Dacascos ), the protagonist's companion. The film opened in France in January 2001 .

Comments on the film:

“The film is about wolves, French aristocrats, secret societies , Iroquois Indians, martial arts, occult ceremonies, sacred mushrooms, boasters, incestuous desire, political infiltration, animal spirits, bloody battle scenes and brothels .

The only thing not to do is take this movie seriously. Its roots are in traditional monster sex fantasy films with special effects. "

watch TV

Another film adaptation of the material was made under the title The Beast of the Old Mountains (La bête du Gévaudan) as a television film, France 2003, with a first broadcast by ARTE on January 7, 2005. Director: Patrick Volson with Sagamore Stévenin (Pierre Rampal), Léa Bosco (Françounette), Jean-François Stévenin (Jean Chastel), Guillaume Gallienne (Abbé Pourcher), Vincent Winterhalter (Comte de Morangie) and Louise Szpindel (Judith).

Comment on the filming:

“The new film adaptation of the legend of the Gévaudan, which is proverbially known in France, captivates with its surprising twists and turns and also raises the question of how much truth there is in each legend. With brilliant photography, magnificent costumes and backdrops as well as gripping action scenes, she seduces into distant times and impresses with acting performances such as the first joint appearance of father and son Stévenin.

Jean-François Stévenin delivers an acting masterpiece in 'The Beast of the Old Mountains'. He modulates his role of the slandered Jean Chastel from a serene outsider to a man who loses his mind after the death of his wife. "

In the mystery series Teen Wolf , the beast is the main antagonist of the fifth season.

museum

The events surrounding the beast of Gévaudan are clearly presented in a museum in Saugues in the canton of the same name . 24 scenes with life-size figures bring the story to life, accompanied by a lively description (in French) and a sound backdrop.

literature

- Jean-Claude Bourret: Le secret de la bête de Gévaudan. Editions du Signe, Paris 2010, ISBN 978-2-7468-2379-2 (Volume 1), ISBN 978-2-7468-2493-5 (Volume 2).

- Pascal Cazottes: La Bete du Gévaudan. Enfin démasquée? Les 3 Spirales, La Motte d'Aigues 2004, ISBN 2-84773-024-9 (somewhat sensational ).

- Michel Louis: La bête du Gévaudan. Perrin, Paris 2001, 2003, ISBN 2-262-02054-X (the author, zoo director in Amneville, subliminally supports the thesis of a wolfhound trained by Chastel).

- Pierre Pourcher: Histoire de la Bete du Gévaudan. Véritable fléau de Dieu, d'après les documents inédits et authentiques. 2 volumes. Saint-Martin-de-Boubaux 1889, Ed. Altaïr, Neuilly-sur-Seine 2000, Lafitte, Marseille 2006, ISBN 2-86276-440-X (contains many documents and reads like a police report).

- Henri Pourrat: Histoire fidèle de la bête du Gévaudan. Edition Laffitte, Paris 1999, ISBN 2-7348-0646-0 .

- Association for cryptozoological research: Der Fährtenleser - Edition 1. Twilight-Line, Edition BOD, Krombach 2007, ISBN 978-3-8334-9382-9 .

- Michael Schneider: Traces of the Unknown. Cryptozoology, monsters, myths and legends. BoD, 2002, ISBN 3-8311-4596-2 .

- Jay M. Smith: Monsters of the Gévaudan. The Making of a Beast. Harvard University Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0-674-04716-7 .

- Richard H. Thompson: Wolf-Hunting in France in the Reign of Louis XV. The beast of the Gevaudan. Edwin Mellen Press, New York 1992, ISBN 0-88946-746-3 .

- Utz Anhalt: serial killer in history. The beast of Gevaudan. In: carbuncle . Magazine for history that can be experienced. Volume 97, 2011, pp. 24-31.

Literary processing

- Élie Berthet : Le Bete du Gevaudan . Hachette 1858 (Colportage novel, German as Der Wolfsmensch , translation Hartleben 1858, 3 vols.).

- Ernst Thompson-Seton: The she-wolf Wosca and other animal and primeval world stories . Goldmann Verlag, Leipzig 1937 (La Bete, the wolf monster by Gevaudan).

- Markus Heitz : Rite . Droemer / Knaur, 2006. ISBN 3-426-63130-X .

- Markus Heitz: Sanctum . Droemer / Knaur, 2006. ISBN 3-426-63131-8 .

- Lynn Raven : Werewolf . Ueberreuter, 2008. ISBN 978-3-8000-5430-5 .

- Nina Blazon : Wolf time . Ravensburger Buchverlag, 2012. ISBN 3-473-40070-X .

- Matthias Fischer : The beast from the Kinzig valley . Emons, Cologne 2018, ISBN 978-3-7408-0304-9 (adaptation of the Gévaudan myth in a contemporary detective novel).

Web links

- Les Loups du Gévaudan (French)

- La bête du Gévaudan - mythe et réalité (French)

- La bête du Gévaudan (multilingual)

- Bête du Gévaudan (Boulevard side, French)

- Solving the Mystery of the 18th-Century Killer “Beast of Gévaudan” (National Geographic, English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Jean-Marc Moriceau: La bête du Gévaudan. L'histoire comme un roman. Paris 2009. Item 3957.

- ^ François Fabre: La bete du Gévaudan. Edition complétée par Jean Richard. Clermont-Ferrond 2002, Appendix: Tableau des victimes de la Bête.

- ^ Jean-Marc Moriceau: La bête du Gévaudan. L'histoire comme un roman. Paris 2009. Appendix: List of victimes tuées de 1764 à 1767.

- ↑ Pierre Pourcher: The Beast of Gevaudan. La Bete du Gévaudan. Bloomington 2007. p. 9; Giovanni Todaro: The Maneater of Gévaudan. When the Serial Killer Is an Animal. Raleigh 2013. Pos. 164.

- ^ Jean-Marc Moriceau: La bête du Gévaudan. L'histoire comme un roman. Paris 2009. Item 774.

- ^ Jean-Marc Moriceau: La bête du Gévaudan. L'histoire comme un roman. Paris 2009. Item 314.

- ^ François Fabre: La bete du Gévaudan. Edition complétée par Jean Richard. Clermont-Ferrond 2002, Appendix: Tableau des victimes de la Bête.

- ↑ Pierre Pourcher: The Beast of Gevaudan. La Bete du Gévaudan. Bloomington 2007. pp. 71ff; Jay M. Smith: Monsters of the Gévaudan. The Making of a Beast. Cambridge 2011. pp. 161ff.

- ↑ Pierre Pourcher: The Beast of Gevaudan. La Bete du Gévaudan. Bloomington 2007. pp. 71ff; Jay M. Smith: Monsters of the Gévaudan. The Making of a Beast. Cambridge 2011. pp. 167f.

- ^ François Fabre: La bete du Gévaudan. Edition complétée par Jean Richard. Clermont-Ferrond 2002, p. 142.

- ↑ Pierre Pourcher: The Beast of Gevaudan. La Bete du Gévaudan. Bloomington 2007. p. 23, p. 44, p. 262ff; Jean-Marc Moriceau: La bête du Gévaudan. L'histoire comme un roman. Paris 2009. Item 2958.

- ↑ Pierre Pourcher: The Beast of Gevaudan. La Bete du Gévaudan. Bloomington 2007. p. 258.

- ^ [1] David Bressan: How An Ancient Volcano Helped A Man-Eating Wolf Terrorize 18th Century France. Forbes, June 28, 2017. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ Jean-Marc Moriceau: La bête du Gévaudan. L'histoire comme un roman. Paris 2009. Item 592.

- ↑ Pierre Pourcher: The Beast of Gevaudan. La Bete du Gévaudan. Bloomington 2007. p. 7, p. 44; Giovanni Todaro: The Maneater of Gévaudan. When the Serial Killer Is an Animal. Raleigh 2013. Pos. 2699.

- ^ Jean-Marc Moriceau: La bête du Gévaudan. L'histoire comme un roman. Paris 2009. Item 2382.

- ^ Jean-Marc Moriceau: La bête du Gévaudan. L'histoire comme un roman. Paris 2009.

- ^ Giovanni Todaro: The Maneater of Gévaudan. When the Serial Killer Is an Animal. Raleigh 2013.

- ↑ Jay M. Smith: Monsters of the Gévaudan. The Making of a Beast. Cambridge 2011. p. 119.

- ^ Jean-Marc Moriceau: La bête du Gévaudan. L'histoire comme un roman. Paris 2009. Item 232.

- ↑ Jay M. Smith: Monsters of the Gévaudan. The Making of a Beast. Cambridge 2011. p. 208.

- ^ Giovanni Todaro: The Maneater of Gévaudan. When the Serial Killer Is an Animal. Raleigh 2013. Pos. 5887, 6187.

- ↑ [2] Karl-Hans Taake: Solving the Mystery of the 18th Century Killer “Beast of Gévaudan”. National Geographic, September 27, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ↑ Jay M. Smith: Monsters of the Gévaudan. The Making of a Beast. Cambridge 2011. p. 242.

- ^ Bernard Soulier: Précisions historiques: On en sait un peu plus sur la fin de la dépouille de la bête de Chastel. In: Gazette de la bete . No. 11, December 2010, pp. 1–4, accessed on December 11, 2018, PDF .

- ^ Haude-Spenersche Zeitung. Berlin 1764, No. 148.

- ^ [3] Karl-Hans Taake: Solving the Mystery of the 18th Century Killer “Beast of Gévaudan”. National Geographic, September 27, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ↑ Süddeutsche Zeitung: Myths in France - The Beast of Gévaudan. Retrieved May 28, 2020 .

- ↑ Abel Chevalley: La Bete du Gévaudan. Paris 1936.

- ↑ Jay M. Smith: Monsters of the Gévaudan. The Making of a Beast. Cambridge 2011. pp. 264ff.

- ^ Paul Puech: La Bete du Gévaudan. In: Aesculape: Revue Mensuelle Illustrée. No. 2, 1912, pp. 9-12.

- ↑ Gérard Ménatory: La Bête du Gévaudan: Histoire, Légende, Réalité. Mende 1976.

- ↑ Michel Louis: La Bete du Gévaudan: L'innocence des loups. Paris 1992.

- ↑ Hervé Boyac: La Bete du Gévaudan: plaidoyer pour le loup. Saint-Auban 2004.

- ^ Jean-Marc Moriceau: Histoire du méchant loup: La question des attaques sur l'homme en France XVe-XXe siecle. Paris 2016. p. 147 ff.

- ^ Jean-Marc Moriceau: Histoire du méchant loup: La question des attaques sur l'homme en France XVe-XXe siecle. Paris 2016. p. 129 ff.

- ^ [4] Karl-Hans Taake: Carnivore Attacks on Humans in Historic France and Germany: To Which Species Did the Attackers Belong? ResearchGate, February 2020. Retrieved on April 23, 2020. pp. 5 ff.

- ^ Louise E. Robbins: Elephant Slaves and Pampered Parrots: Exotic Animals in Eighteenth-Century Paris. Baltimore 2002. pp. 7-99.

- ↑ Original: “The one thing you don't want to do is take this movie seriously. [...] Its heart is in the horror-monster-sex-fantasy-special effects tradition. "

- ↑ arte.tv: The Beast of the Old Mountains ( Memento from July 21, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )