Black Maria

The Black Maria [ blæk maˈɹiːa ] ( English for Black Maria ) was the first commercial film studio in the world. It was built in 1892 by film pioneer William KL Dickson on the grounds of Thomas Alva Edison's laboratories in West Orange , New Jersey , and served as the production facility for the Edison Manufacturing Company's films from 1893 to 1901 .

The films from the Black Maria Studio are among the oldest recordings in film history . The films, mostly less than a minute long, were initially marketed in kinetoscopes , and from 1896 onwards the films were also projected onto the screen. On the small stage of the Black Maria mainly performances by well-known circus artists and vaudeville artists, simple scenes from the everyday world and short excerpts from stage plays were filmed.

Competition from other film producers, the increased interest in films that were shot on location, and the limited space in the Black Maria led to the relocation of film production to New York in 1901 and the demolition of the abandoned building two years later. In 1954, a replica of the studio was built on the site of the Edison Laboratories.

History of the Black Maria

Development of the Edisonian film camera

Inspired by the series photographs by Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey , Thomas Alva Edison first formulated the idea in 1887 of developing a device that could record and reproduce “moving images”. He had in mind an instrument similar to his phonograph, which he had developed ten years earlier, for recording speech and music. The Scottish engineer William KL Dickson was commissioned with the development work on the device known as the kinetoscope in the fall of 1888, and he was able to bring in the necessary experience as an amateur photographer.

At first, Dickson tried to record single images on a specially prepared roller, analogous to the phonograph. However, this arrangement proved to be impractical, although the first test films were completed in October 1890. After reports from Marey and William Friese-Greene on the use of celluloid film , Dickson turned to this new film medium and finally developed an electrically operated film camera, the kinetograph , with which film rolls could be exposed 46 times per second. The kinetoscope was developed as a viewing device, a peep box in which the developed film strips were illuminated in an endless loop with an Edison incandescent lamp and viewed through a magnifying glass.

The first experimental film, the Dickson Greeting strip, which lasted only a few seconds , was taken with the cinetograph in May 1891 and shown to a group of visitors on May 20, 1891 in the photographic laboratories of the Edison Manufacturing Company . In the months that followed, both the camera and the viewing device continued to improve. The kinetograph and kinetoscope were patented in August 1891, and both devices were further revised by 1893.

In October 1892, Dickson had improved the camera so much that Edison could prepare the presentation of Dickson's invention at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago and plan a commercial use of the kinetoscope. For this, however, the production of further films was necessary. As the size, weight and immobility of the kinetograph made it difficult to use in normal laboratories, it was decided to build a separate building for the shooting.

Establishment of the studio

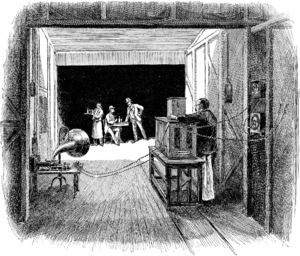

Dickson designed a building that provided a small stage and space for the film equipment. The wooden building was around 15 m long and 4 m wide. Due to the low sensitivity of the film material used to light , the roof of the building could be opened so that the sunlight could be used for exposure . In order to guarantee optimal lighting, the structure was erected on a rotating platform. In addition, four powerful magnesium lamps were installed. In order to prevent disturbing incidence of light and to achieve the greatest possible contrast between the filmed events and the background on stage, the studio was completely lined with black tar paper . Dickson proudly described that his building did not comply with any architectural laws and did not follow conventions in the materials used or in the color scheme.

The black color and the narrowness within the building meant that the Kinetographic Theater , the studio's official name, was nicknamed "Black Maria" in reference to the black painted prisoner transporter .

Construction began on the Edison Manufacturing Company site in December 1892 and the Kinetographic Theater was completed on February 1, 1893. Construction costs were $ 637.67. However, the start of filming in the new building was delayed due to further modifications to the film camera and Dickson's poor health.

Work in the Black Maria finally began at the end of April 1893. The oldest known film from this studio is the Blacksmith Scene , a nostalgic scene in which three of Edison's employees appeared as blacksmiths. Dickson attacked with this film already a photographed by Eadweard Muybridge subject to. The film, only about 30 seconds long, was shown on May 9, 1893 at a presentation by Edison to the Faculty of Physics at the Brooklyn Institute for Arts and Sciences.

The demonstration of the Kinetoscope at the Chicago World's Fair , which was also planned for May, did not take place, however, despite advance notice. The background to this was the delay in the production of the viewing devices after a new prototype had only been completed shortly before the presentation in Brooklyn. The series production of 25 more devices was finally delayed until March 1894. Because of these production problems, which accompanied an economic crisis in the United States, only a few films were made for demonstration purposes in 1893.

Commercial film production begins

At the beginning of 1894, efforts to market the kinetoscope were intensified. In the first week of January, Dickson filmed his assistant Fred Ott taking a pinch of snuff and then sneezing heartily. This film, titled Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze (better known as Fred Ott's Sneeze ) was registered for US copyright on January 9, 1894 by Dickson as the first film in history . The film was made after a request from Harper's Weekly magazine , which reprinted frames from this film in March 1894.

In the following months, Dickson and his assistant, William Heise, worked on other films that were being prepared for the first commercial presentation in the spring. A visit by the famous strength athlete Eugen Sandow to Edison's laboratories triggered great public interest on March 6th . After meeting Thomas Alva Edison, he was filmed doing his warm-up exercises in the Black Maria . Other vaudeville artists followed Sandow's visit. Also in March women were filmed for the first time with the dancer Carmencita and the contortionist Ena Bertoldi. With other films such as Cock Fight , which showed a cockfight in close-up, and a bar room scene that was arranged similarly to the Blacksmith Scene , Dickson and Heise created films that were particularly intended to appeal to a male audience.

On April 1, 1894, the marketing of the kinetoscope was finally transferred from the Edison Laboratories to the Edison Manufacturing Company . Up to this point in time, the development costs for the Kinetograph and Kinetoscope, including the construction and operation of the Black Maria, were more than $ 24,000. After the first ten kinetoscopes were finally completed with a one-year delay, a shop operated by the Holland Brothers was able to be equipped on Broadway in New York. The Kinetoskop Salon was opened on April 14, 1894 and caused a sensation on the very first day. Ten different films were shown (a different film in each kinetoscope), including the first film Blacksmith Scene, which was completed at Black Maria . Five devices each could be used one after the other for the entrance fee of 25 cents.

In mid-May 1894 another salon in Chicago was equipped with ten kinetoscopes; the last five devices of the first production series were presented to the public on June 1 in San Francisco . The Edison Manufacturing Company had meanwhile taken over the production of the kinetoscopes and fulfilled requests for devices from all over the United States. In October 1894 the first overseas kinetoscope salons were opened in Paris and London , followed by salons in Germany , the Netherlands and Australia by the end of the year .

Commercial successes

Since the Kinetoskop was hailed by the press as a "new attraction", numerous artists visited the film studio in nearby West Orange during their guest appearances in New York in order to participate in the fame themselves with their film appearances. In addition to circus artists from Barnum and Bailey , artists from the vaudeville stages were welcome guests. Both Professor Harry Welton's cat circus and Professor Ivan Tschernoff's trained dogs appeared in front of the camera. In July 1894, the cinetograph was first used outside the Black Maria to film the high wire artist Juan Caicedo. The dancer Annabelle Whitford performed her art several times in the Black Maria between 1894 and 1898 , some of these films were later hand-colored .

In the fall of 1894, several performers from Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show appeared in front of Edison's camera. Besides the art shooter Annie Oakley and Buffalo Bill personally multiple scenes with dancing were Sioux - Indians added. Once again, the camera, which is difficult to transport, was used outside the Black Maria to film the rodeo star Lee Martin on a wildly rearing horse.

At the end of November 1894 the most elaborate films to date were staged in the Black Maria . For the recording of scenes from the musical burlesque A Milk White Flag , a 34-member marching band was forced into the narrow studio. A few days later a scene with firefighters was filmed. In order to enable a realistic representation in the studio, smoke bombs were used. The film Fire Rescue Scene thus marked the first use of special effects in Edison's films.

In addition to the filmed vaudeville and circus numbers as well as the genre films from the world of work, the filmmakers of Black Maria discovered a new field of work with the staging of boxing matches . With prize boxing banned in much of the United States, Edison's distribution partners expected high sales of such films. On June 15, 1894, boxers Michael Leonard and Jack Cushing competed against each other in front of the camera in a six-round bout. Because of the limited space, the improvised boxing ring in the Black Maria was smaller than usual and a round lasted only a minute. So that a lap could be completely recorded, 150-foot-long rolls were used instead of the usual 50- foot (around 15-meter) long negative strips, and the recording speed was reduced from 46 to 30 frames per second. Thus the longest films in history were made during the boxing match.

Larger kinetoscopes were constructed for the longer film strips and were first used in New York in August 1894. The viewers could watch the six rounds one after the other on the viewing devices, but had to pay 10 cents for each individual round. Nevertheless, the films were a great success, which is why the reigning boxing world champion "Gentleman Jim" Corbett competed in the Black Maria in a highly endowed exhibition match against Peter Courtney on September 7th . Corbett's sixth-round knockout win was covered extensively in the newspapers and the films were sold well across the United States. As a result, further duels were arranged in the Black Maria , with fencing and sword fights being staged in addition to fist fights.

stagnation

At the beginning of 1895, enthusiasm for the kinetoscope began to wane. The sales figures for the viewers and movies stagnated And it came up with Herman Caslers Mutoscope a competing product on the market. Since Edison Dickson's developments were only protected by patents in the United States, several European inventors were working on replicas of the cinetograph at the same time.

Edison responded by announcing that it would offer films with suitable background music. With the Kinetophon, Dickson had developed a device that could simultaneously play a film and a phonograph cylinder. Even if attempts were made to reproduce sound in sync with the unpublished Dickson Experimental Sound Film , independently recorded sound rollers were offered for the films in the Kinetophones available from March 1895. However, the new system hardly met with interest from customers, only 45 Kinetophones were sold.

Edison experienced another setback when William KL Dickson unexpectedly left the company. Dickson drew the consequence of months of disputes with the managing director of the Edison Company, William E. Gilmore, and different views with Edison about the future of film technology. While Dickson was convinced of the possibility of film projection , Edison wanted to stick to the kinetoscope for economic reasons.

After Dickson's departure, William Heise was initially solely responsible for film operations in Black Maria . His efforts to keep the film production going were unsuccessful. The main attraction of the previous year no longer attracted people in the summer of 1895, the first kinetoscope salons made losses. Edison's business partners urged the development of a film projector after the Latham brothers' first successful attempts at their eidoloscope became public.

In August 1895, Alfred Clark was hired as director of film production. He developed new material for Edison's films by venturing into historical subjects. Although a mobile camera was still not available, Clark had several films shot outside of the studio outdoors, including The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, the first film with a stop-motion effect. But even these new films could not stop the waning interest in the kinetoscope. Clark initially returned to the usual recordings of acrobats and dancers and left the film business a short time later. At the end of 1895, film production in the Black Maria came to a complete standstill after Edison's sales partner had failed to find buyers for new kinetoscopes for several weeks.

Resuscitation through the Vitascope

In 1896 the developing film industry went through radical changes. Birt Acres and Robert William Paul in London, the Skladanowsky brothers in Berlin and above all the Lumière brothers in Paris used their film projectors very successfully for mass entertainment at the beginning of the year; the cinema was born. After Edison's technicians failed to develop their own projector, a system developed by Charles Francis Jenkins and Thomas Armat was bought by the Edison Company and announced in the spring of 1896 as Thomas Alva Edison's latest invention under the name Vitaskop .

The first public demonstration of the Vitascope took place on April 23, 1896 in New York. For the most part, films were shown that had been recorded in the Black Maria for use in kinetoscopes in previous years , including a scene from A Milk White Flag and a colored film with the dancer Annabelle Whitford. The only new film at the Vitascope premiere was RW Paul's Rough Sea at Dover ; this turned out to be the most popular film of the evening.

The success of Rough Sea at Dover made it clear to the Edison Company that new films had to be produced to market the Vitascope. After months of inactivity, however, the Black Maria was in a dilapidated condition. Since the roof could no longer be closed completely, it was cold and drafty on the studio stage. Several artists refused to appear in front of the camera under these conditions. Only warmer weather and the appointment of James H. White as the new head of film production made it possible to resume regular work in the Black Maria in April .

Mid-April in the Black Maria on behalf of the newspaper New York World a scene with the actors May Irwin turned and John C. Rice. The scene was from the play The Widow Jones and showed the final kiss between the protagonists. The resulting film The Kiss was shown for the first time at the end of April and became the most successful film of the year.

A month later, a portable film camera was completed in the Edison laboratories. This camera made it possible for the Edison Company for the first time to take outdoor recordings without major technical effort and thus to compete with the documentary films (actuality films) of the Lumière brothers and RW Pauls. One of the most impressive films made by this new camera was footage of Niagara Falls .

The new film camera also competed with the cumbersome installation in the Black Maria . The actuality films not only turned out to be extremely popular, but were also significantly cheaper than the films that were shot in the Black Maria . Previously, the actors and artists had to go to New Jersey, but thanks to the portable camera, they could now be filmed directly in the theater. In addition, an improvised studio was set up on the roof of the headquarters of the sales company Raft & Gammon , which was used in parallel to Black Maria at least in the summer months of 1896 .

In the summer of 1896, the Vitaskop was presented in other cities in the United States, but was increasingly harassed by the Cinématographe der Lumières and Latham's Eidoloscope. In September, the American Mutoscope Company, co-founded by William KL Dickson, finally presented the Biograph, a technically superior system. Edison's customers were increasingly complaining not only about the poor photographic quality of the films, some of which were two and a half years old, but also about the technical condition of the film copies. Edison reacted and parted with the Vitascope, which became obsolete within a few months, and developed his own improved projector with the Projecting Kinetoscope . It became increasingly clear that Edison could make more profit from the sale of the films than from the distribution of the film projectors. While sales of projectors achieved sales of around $ 21,000 in fiscal 1896, sales of films were more than $ 84,000.

Competition

In the winter of 1896/97 the production of new films was intensified. Since the European films had a great attraction for the audience, James H. White and William Heise tried to recreate motifs from the Lumière film and to record numerous railway films based on the British model, in which they filmed train journeys from the perspective of the train driver. The Black Maria was also used increasingly in the winter months. Thomas Alva Edison stood in front of the camera for the first time and played the ingenious inventor in a replica laboratory in Mr. Edison at Work in His Chemical Laboratory .

In order to react to the increasing popularity of the Biograph films, topical films were increasingly shot again from the spring of 1897 . In the summer of 1897, White decided to embark on an extensive journey, first through the United States, then to Mexico and finally to Japan and China . White was accompanied on the ten-month long journey by camera operator Frederick W. Blechynden. Heise stayed behind in New Jersey and was primarily responsible for developing the negatives sent by White , but also made around 25 of his own films during this time. Only some of these films were made in the Black Maria , including the comedy What Demoralized the Barbershop Heises most successful film of 1898.

Even before White's return, the American public was shaken by the outbreak of the Spanish-American War . The war came at an opportune time for the fledgling film industry as interest in the screenings gradually waned. Biograph was the first to recognize the possibility of winning back audiences with patriotic films. The first films were made about the explosion of the USS Maine , which triggered the war. Biograph's film programs ended with views of the US flag and were enthusiastically celebrated. Edison had to react to the success of the biographer, who had meanwhile developed into the leading film producer in the United States, and also began to produce war films. For lack of his own resources, an independently producing cameraman was sent to Cuba, in addition, Edison bought films from the newly founded Vitagraph Company to meet the demand for pictures from the war. Only after White's return to West Orange, the main cast who could Edison Company contribute to the production of patriotic films by battle scenes on camera readjusted were.

The Black Maria played a minor role at this time. The stage was only used for short comedies in which White himself appeared several times in front of the camera, for example in the film series Adventures of Jones or the film The Astor Tramp, which is based on a popular song . With films like Cripple Creek Bar-Room Scene , White anticipated the development of the western . In view of the growing dependence on supplying film producers - White and Heise were only responsible for half of the films distributed by Edison - the Edison Manufacturing Company fell into a serious crisis in 1899. While Biograph had continued to expand their film production, the film business at Edison stagnated. Sales fell from $ 84,000 in 1896 and $ 75,000 in 1897 to just $ 39,000 in 1899, with production costs for individual films increasing significantly. An expedition to produce exclusive footage of the gold prospectors on the Klondike River turned into a financial failure. In this situation, Edison was on the verge of selling his film production to Biograph, but the deal failed at the last second due to financing problems.

End of film production in West Orange

In the fall of 1900, the Edison Company made a fresh start. Both the film cameras and the projectors were given a general overhaul. With Edwin S. Porter , a new employee was hired who, as a projectionist, had a great deal of experience in handling the apparatus. After just a few months, Porter was also employed as a cameraman and director and became the most important American filmmaker in the first half of the 1900s , especially with The Great Train Robbery.

The Edison Company also decided to build a new studio in Manhattan, New York . The Black Maria no longer met the requirements of a modern film studio. Since films that were assembled from several shots were slowly gaining acceptance, studio scenes were shot in increasingly complex sets. The Black Maria did not offer enough space for this. They also wanted to become more independent from the weather, which is why the new studio was given a glass roof. The new studio guaranteed continuous film production and made Edison less dependent on suppliers such as Vitagraph. In January 1901 the studio in Manhattan was moved. The Black Maria remained unused and was demolished two years later.

In fact, the Edison Company managed to catch up with its competitors, especially after Edison won several lawsuits against its competitors for patent infringement. In 1908 Edison succeeded in controlling the US film market with the Motion Picture Patents Company . Artistically, however, Edison's films developed little further and in 1918 film production was finally discontinued.

For the premiere of the biopic The Great Edison , a replica of the Black Maria was built in 1940 , but this did not survive. It was not until September 1954, a year before the Edison Laboratories were designated a National Historic Site , that a reconstruction of the Black Maria was completed near the original site and can still be viewed today. Since 1981, the former film studio has given its name to the Black Maria short film festival organized by New Jersey City University .

Film historical evaluation of the films from the Black Maria

Even if the brothers Lumière and Thomas Alva Edison were referred to as the fathers of film in earlier years, in retrospect one can neither name an individual inventor nor an exact time when the film was invented. Dickson's film camera had precursors not only in the cameras of Louis Le Prince , William Friese-Greene or Émile Reynaud , but also in the zoetrope and the magic lantern . Even so, the Black Maria is considered by film historians like Leonard Maltin to be the birthplace of the film industry, as this is where the first commercially distributed films were produced.

Unlike the first recordings made by the European film pioneers, which mostly showed urban or rural views, Dickson and Heise's early recordings were made exclusively in the Black Maria . The immobility of the cinetographer made the establishment of the studio necessary. According to film historian Charles Musser, the black lining of the studio stage was both technically and aesthetically justified. The black background concealed the motif's lack of spatial depth and was intended to be reminiscent of Muybridge's and Marey's studies of movement. According to Tom Gunning, the focus was not on the image design , but on the strong stylization of the movement. It was precisely these seemingly simply staged films from Black Maria that led to American films being viewed by many historians as naive, primitive and unfinished before the turn of the century. The film historian Thomas Elsaesser, on the other hand, sees this stylization as an anticipation of the classic Hollywood film; the Black Maria was a prototype of the Hollywood studio system .

The films from the Black Maria not only reflected the aesthetics of 19th century photography. Paul C. Spehr pointed out that Edison had seen the cinetograph as a logical continuation of the phonograph from the start. Both were used to record something permanently. In analogy to the phonograph records of the first films to which Dickson applied for copyright, they were referred to as Kinetoscope records . Just as the sound recordings commercially sold by Edison mainly came from the field of light music, circus and vaudeville artists were preferred to be filmed with the cinetograph in the early years. With the introduction of the Vitaskop film projector, however, the repertoire of films shifted to short scenes from plays such as The Kiss from the musical The Widow Jones . David Robinson sees here an alignment of the themes to the demonstrations of the magic lantern. Despite the increasingly elaborate staging, which, influenced by the success of the Biograph, required the installation of stage sets in the Black Maria , the later films from the Black Maria studio also contained few narrative elements. The films remained typical examples of the cinema of attractions until the very end .

Much like the vaudeville stages, the Edison Company's early films were aimed at middle-class audiences. It was only with the projection of films that the new medium opened up to the working class, who adopted it in the Nickelodeons at the beginning of the 20th century . According to W. Bernard Carlson, Edison failed in this transition period - Edison's mindset was still ingrained in the 19th century, while in the late 1890s both the culture and society of the United States were changing. The films from the Black Maria were thus aimed at a dwindling audience, while the broad masses were drawn to the films from France and by Biograph, which were more in the working class . Even in Dickson's early films such as Blacksmith Scene, Musser sees a nostalgic transfiguration of the world of work, which was in stark contrast to the realism of the first films by the Lumière brothers.

Even more noticeable than the focus of the cinematic themes on the middle class is the focus on a male audience, which, according to Robinson, was recognized as the target group of the Edison Company even before the opening of the first Kinetoskop Salon in April 1894 . Charles Musser sees the origin of these expectations in the homosocial environment in which the films were made. Only men were involved in the development of Edison's camera, and so only men appeared in Edison's first films. The male working world, as it was portrayed in the Blacksmith Scene , corresponded to the experiences of the first filmmakers. When the dancer Carmencita became the first woman to appear in front of the camera (see Carmencita ), she was filmed as a sex object that satisfied male voyeurism . In addition to sexuality (which is restrained from today's perspective), male violence dominated the early films from the Black Maria studio. Boxing matches, cockfights and unusual films like the one of terriers tearing rats up in front of the camera caused a sensation. It was only when women began to enjoy the Kinetoskop salons that the Edison Company's repertoire changed and eventually became more family-friendly with the projections.

Selected films

Blacksmith Scene (1893)

Annie Oakley (1894)

Serpentine Dances (1895)

The Kiss (1896)

literature

- Neil Baldwin: Edison: Inventing the Century . University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2001, ISBN 0-226-03571-9 .

- WKL Dickson and Antonia Dickson: History of the Kinetograph, Kinetoscope and Kinetophonograph . Albert Brunn, New York 1895; Reprint: Museum of Modern Art, New York 2000, ISBN 0-87070-038-3 .

- Charles Musser: Before the Nickelodeon. Edwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 1991, ISBN 0-520-06986-2 .

- Charles Musser: The Emergence of Cinema. The American Screen to 1907 (= History of the American Cinema. Vol. 1). University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 1994, ISBN 0-520-08533-7 .

- Charles Musser: At the Beginning: Motion picture production, representation and ideology at the Edison and Lumière companies . In: The Silent Cinema Reader (Eds. Lee Grieveson and Peter Krämer). Routledge, London 2004, ISBN 0-415-25284-9 , pp. 15-30.

- Robert Pearson: Early Cinema . In: The Oxford History of World Cinema , Oxford University Press, Oxford 1996, ISBN 0-19-874242-8 , pp. 13-23.

- David Robinson: From Peep Show to Palace: The Birth of American Film . Columbia University Press, New York 1996, ISBN 0-231-10338-7 .

Web links

- History of Edison Motion Pictures , the website Library of Congress (English)

- Edison National Historic Site , West Orange film making history website

- Edison: The Invention of the Movies , material accompanying the DVD box from Kino Video (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Robinson: From Peep Show to Palace , p. 22.

- ^ Charles Musser: Edison Motion Pictures, 1890-1900: An Annotated Filmography . Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington 1997, ISBN 8-886-15507-7 , p. 73.

- ↑ Laurent Mannoni, Donata Pesenti Campagnoni and David Robinson: Light and Movement: Incunabula of the Motion Picture, 1420-1896 . BFI Publishing, London 1996, ISBN 88-86155-05-0 , pp. 333-339.

- ↑ Phonogram: The Kinetograph , October 1892, pp. 217-218.

- ↑ a b Pearson: Early Cinema , p. 15.

- ↑ a b Carles Musser: Before the Nickelodeon , University of California Press, ISBN 0520069862 , p. 32. (English, [1] , accessed on January 31, 2018)

- ↑ Antonia and WKL Dickson: Edison's Invention of the Kineto phonograph . In: Century Magazine, Vol. 48, No. 2, June 1894, p. 210.

- ^ A b W. KL Dickson: Edison's Kinematograph Experiments . In: Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly , No. 7, 1907, p. 103.

- ↑ The expression “black maria” can therefore be compared with the term “ Green Minna ”.

- ↑ Chase's Calendar of Events 2007 , McGraw Hill Professional, 2006, ISBN 0-07-146819-6 , p. 109. (English, limited preview in Google Book Search, accessed on January 31, 2012)

- ↑ a b Robinson: From Peep Show to Palace , p. 40.

- ^ Scientific American : First Public Exhibition of Edison's Kinetograph , May 20, 1893, p. 310.

- ↑ Gordon Hendricks : A New Look at an 'Old Sneeze' . In: Film Culture , No. 22-23, 1961, pp. 90-95.

- ↑ Orange Chronicle: Sandow at the Edison Laboratory , March 10, 1894, p. 5.

- ↑ a b c Robinson: From Peep Show to Palace , p. 43.

- ↑ Musser: The Emergence of Cinema , p. 75.

- ^ New York World, June 7, 1894, p. 21.

- ↑ Musser: Before the Nickelodeon , p. 51.

- ^ Musser: The Emergence of Cinema , pp. 82-83.

- ^ New York Sun: Knocked Out by Corbett , September 8, 1894.

- ^ Robinson: From Peep Show to Palace , p. 50.

- ↑ Rick Altman: Silent Film Sound . Columbia University Press, New York 2004, ISBN 0-231-11662-4 , p. 81.

- ^ Robinson: From Peep Show to Palace , pp. 53-55.

- ^ Asbury Park Daily Press: Kinetoscope Scenes , Aug. 2, 1895.

- ^ Gordon Hendricks : The Kinetoscope: America's First Commercially Successful Motion Picture Exhibitor . Theodore Gaus' Sons, New York 1966, p. 138.

- ↑ Musser: Before the Nickelodeon , pp. 57-60.

- ^ The New York Times : Edison's Vitascope Cheered , April 24, 1896 (accessed September 23, 2008).

- ^ New York Herald , April 24, 1896, 11.

- ↑ Musser: Before the Nickelodeon , p. 64.

- ↑ New York World : The Anatomy of a Kiss , April 26, 1896, p. 21.

- ^ Boston Herald, Aug. 4, 1896, p. 7

- ↑ Terry Ramsaye: A Million and One Nights: A History of the Motion Pictures Through 1925 . Simon & Schuster, New York 1926, p. 257.

- ^ Charles Musser: Introducing Cinema to the American Public: The Vitascope in the United States, 1896–7 . In: Moviegoing in America: A Sourcebook (Ed. Gregory A. Waller). Blackwell Publishers, Malden 2002, ISBN 0-631-22592-7 , pp. 13-26.

- ↑ Musser: Before the Nickelodeon , p. 93.

- ^ Robinson: From Peep Show to Palace , p. 73.

- ^ New York World: Patriotism at Theaters Shows No Diminution , March 8, 1898.

- ↑ Musser: Before the Nickelodeon , p. 150.

- ↑ Corinna Müller and Harro Segeberg: The modeling of the cinema film: On the history of the cinema program between short film and feature film 1905 / 06–1918 . Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-7705-3244-9 , p. 97.

- ↑ Musser: Before the Nickelodeon , p. 143.

- ↑ Musser: The Emergence of Cinema , p. 281.

- ↑ Musser: The Emergence of Cinema , p. 283.

- ^ Pearson: Early Cinema , p. 16.

- ↑ The New York Times : Of Local Origin, August 28, 1954 (accessed September 24, 2008).

- ^ Website of the Black Maria Film Festival (accessed September 23, 2008).

- ^ Deac Rossell: Living Pictures: The Origin of the Movies . State University of New York Press, Albany 1998, ISBN 0-7914-3767-1 , p. 1.

- ^ Leonard Maltin : The Whole Film Sourcebook . New American Library, New York 1983, ISBN 0-452-25361-6 , p. 407.

- ↑ Musser: The Emergence of Cinema , p. 78.

- ↑ Tom Gunning: New Thresholds of Vision . In: Impossible Presence: Surface and Screen in the Photogenic Era (Ed. Terry Smith). University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2001, ISBN 0-226-76384-6 , pp. 75-78.

- ↑ Musser: Before the Nickelodeon , p. 162.

- ↑ Thomas Elsaesser: Film history and early cinema - archeology of a media change . edition text + kritik, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-88377-696-3 , p. 52.

- ^ Paul C. Spehr: The Movies Begin: Making Movies in New Jersey, 1887–1920 . Newark Museum Association, Newark 1977, ISBN 0-87100-121-7 .

- ↑ Edison had previously coined the term "record" for music recordings, see Evan Eisenberg: The Recording Angel . Yale University Press, New Haven 2005, ISBN 0-300-09904-5 , p. 89.

- ^ Robinson: From Peep Show to Palace , pp. 69-71.

- ↑ Tom Gunning: The Cinema of Attraction: Early Films, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde . In: Wide Angle , Vol. 8, No. 3/4, 1986, pp. 63-70.

- ↑ Kevin Brownlow : Pioneers of Film . Stroemfeld Verlag, Basel 1997, ISBN 3-87877-386-2 , pp. 28-29.

- ^ W. Bernard Carlson: Artifacts and Frames of Meaning: Thomas A. Edison, His Managers, and the Cultural Construction of Motion Pictures . In: Shaping Technology / Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change (Eds. Wiebe E. Bijker and John Law). MIT Press, Cambridge 1992, ISBN 0-262-52194-6 , pp. 177-178.

- ^ Musser: At the Beginning , pp. 16-18.

- ↑ Musser: At the Beginning , p. 21.

- ↑ Musser: At the Beginning , p. 22.

- ↑ Musser: Before the Nickelodeon , p. 44.