C / 1743 X1

| C / 1743 X1 [i] | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

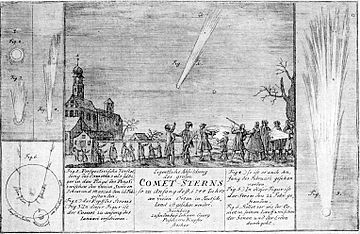

The stripes in the comet's tail

on March 8, 1744 |

|

| Properties of the orbit ( animation ) | |

| Orbit type | parabolic |

| Numerical eccentricity | 1.0 |

| Perihelion | 0.222 AU |

| Inclination of the orbit plane | 47.1 ° |

| Perihelion | March 1, 1744 |

| Orbital velocity in the perihelion | 89.4 km / s |

| history | |

| Explorer | Jan de Munck , Dirk Klinkenberg , Jean-Philippe de Chéseaux |

| Date of discovery | November 29, 1743 |

| Older name | 1744 |

| Source: Unless otherwise stated, the data comes from JPL Small-Body Database Browser . Please also note the note on comet articles . | |

C / 1743 X1 or Komet Klinkenberg (also Komet de Chéseaux or Komet Klinkenberg-Chéseaux ) was a comet that could be seen with the naked eye in 1743 and 1744 . It was one of the brightest comets of the 18th century and is counted among the " Great Comets " due to its extraordinary brightness .

Discovery story

For a long time it was accepted that the comet was discovered independently of each other on December 9th at 9 p.m. by the amateur astronomer Dirk Klinkenberg in Haarlem (Holland) and on December 13th by the astronomer and mathematician Jean-Philippe Loys de Chéseaux in Lausanne . Since Chéseaux was the better known of the two as an astronomer and calculated the first orbit elements of the comet, the comet is often associated with his name, but Klinkenberg is also often mentioned.

It was not until a century and a half later that documents with observations of the comet were found in a library in Utrecht in 1894 , which were already made 10 days before Klinkenberg on November 29, 1743 by his compatriot, the architect Jan de Munck , in Middelburg . The official designation of the tail star should therefore actually be C / 1743 W1 (de Munck) .

Chéseaux initially described his discovery as a nebulous 3rd mag star with a small tail . On December 21st, Jacques Cassini from Paris observed him as an object of the 2nd size class. After the turn of the year, first observations of the comet followed in other places, such as on January 3, 1744 in the observatory of the Earl of Macclesfield in Shirburn Castle near Oxford, and also on January 3, 1744 in Berlin by Margaretha Kirch . De Munck was also able to continue his observations after a weather-related interruption from January 3 to February 6.

In China , the comet was first seen on January 4th and described as a "broom star" of yellowish-white color and "the size of a pearl". Its 1.5 ° long tail pointed to the east. The Chinese scientists observed the comet until February 25th.

Further observations

In the course of January the comet moved slowly to the west without increasing its brightness or developing a tail longer than 6–8 °. On January 25, Gottfried Heinsius observed a sun-directed jet or a fountain of material evaporating from the core in Saint Petersburg .

In February the comet developed more clearly: on February 7th, according to Cassini, it had reached a tail length of 20 °. A week later, the comet was brighter than all the stars in the night sky except Sirius . The tail had now also divided, Cassini reported on February 15 of a 24 ° long western branch and a 7-8 ° long eastern branch. On February 20, the comet reached a magnitude of −3 mag. By the end of the month it was already as bright as Venus in the morning sky and the tail was curved to the west.

On February 25, Gianpaolo Guglienzi and Jean-François Séguier were able to see the comet in Verona in the evening just before sunset, and on February 28, just a few minutes before sunrise in the morning. At noon that day, they saw him both with telescopes and with the naked eye 12 ° next to the sun in the bright sky. This was the first telescopic daytime observation of a comet. Even James Bradley looked at him this afternoon from Oxford .

From the beginning of March, the comet's head was no longer visible at dawn, but observers saw the tail rise above the horizon. On March 1, Cassini reported a tail up to 15 ° altitude. On this day the perihelion of the comet took place, after which the comet could be observed more and more from the southern hemisphere . On March 3, before and during sunrise, an observer was able to see a 10 ° long tail from a ship off Western Australia .

From March 5-9, the comet's tail was seen by several observers in Europe, including de Chéseaux, as a multiple system at dawn. A fan of up to twelve tails protruded over the eastern horizon, while the comet's head remained unobservable because of the nearby sun.

From mid-March the comet could only be seen from the southern hemisphere. Dutch sailors saw him from a ship south of Madagascar on the voyage to Brazil from March 18 to April 22, initially with a tail 80–90 ° long. After that, no further observations are known.

Charles Messier was able to observe the Great Comet of 1744 when he was thirteen. Impressed by this magnificent appearance, Messier devoted his later life to the search for new comets.

Scientific evaluation

Based on various observations, orbit elements for the comet have already been calculated in a short time by nine astronomers, including Chéseaux, Klinkenberg, Giovanni Domenico Maraldi and Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille (Paris), Leonhard Euler (Berlin), Alexandre Guy Pingré (Rouen) and others . All calculations gave very similar results.

For a long time, it was more difficult to explain the interesting phenomenon of the apparently fanned out tail, which de Chéseaux had observed and recorded on the morning of March 8 and 9, 1744. His illustration shows six complete tails of varying curvature rising above a dimly lit horizon, with dotted lines extending the tails below the horizon until they meet at the presumed location of the comet's head . This sketch was only intended to show how he imagined the situation, which was not directly visible. Since the observers in the southern hemisphere had not reported anything like this, the observation of de Chéseaux was doubted for a long time. It was only when lesser-known reports by Margaretha Kirch from Berlin , as well as Joseph-Nicolas Delisle and Gottfried Heinsius from Saint Petersburg from March 5th to 7th, which even document up to 12 distinctive features, were found that de Chéseaux was found in his observations on the following two days had probably only observed the reflection of the phenomenon.

The observed phenomena were probably not comet tails in the strict sense. For one thing, their number changed within a short period of time, so it must have been something shorter-lived than a real dust tail. In addition, they were directed in the "wrong direction", namely not away from the sun, but almost at right angles to an imaginary line between the sun and comet. There were thus parallel stripes ( striae ) arranged across the comet's single, strongly curved dust tail . This explanation was confirmed by Comet C / 2006 P1 (McNaught) observed in January 2007 , which exhibited a very similar phenomenon.

Another previously unexplained effect is described in Chinese reports that atmospheric noises occurred when the comet appeared. Similar effects are said to have already occurred with particularly strong polar lights and may indicate interactions with the earth's magnetic field .

Orbit

Although the comet was observed for several months , due to the insufficiently precise observation information , only a parabolic orbit with limited precision could be determined, which is inclined by around 47 ° to the ecliptic . At the point of the orbit closest to the sun ( perihelion ), which the comet passed on March 1, 1744, it was located at a distance of about 33.2 million km from the sun within the orbit of Mercury . By February 26th, it had already approached the earth to about 0.83 AU / 123.6 million km. Around March 7th it came close to Venus to about 70 million km.

The comet is unlikely to return to the inner solar system , or will return many tens or hundreds of thousands of years .

See also

Individual evidence

- ^ M. Kirch: Gewitter Observationes 1744. MK The manuscript is today in the Crawford Library of the Royal Observatory Edinburgh. A copy was published by Leonhard Euler in L. Euler, EJ Aiton (Ed.): Commentationes mechanicae et astronomicae ad physicam cosmicam pertinentes. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel 1996, ISBN 3-7643-1459-1 , p. 182 ff. Under the heading "The following cometic observations are made by a skilled woman ...". Further details can also be found in a footnote on page XLVI of the introduction to the same work.

- ^ WT Lynn: Lord Macclesfield and the Great Comet of 1744 . In: The Observatory , Vol. 35, 1912, pp. 198-199. ( bibcode : 1912Obs .... 35..198L )

- ^ Donald K. Yeomans: NASA JPL Solar System Dynamics: Great Comets in History. Retrieved June 17, 2014 .

- ^ A b D. AJ Seargent: The Greatest Comets in History: Broom Stars and Celestial Scimitars . Springer, New York, 2009, ISBN 978-0-387-09512-7 , pp. 116-119.

- ^ GW Kronk: Cometography - A Catalog of Comets, Volume 1. Ancient - 1799 . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-58504-0 , pp. 408-411.

- ^ A b Martin Mobberley: Hunting and Imaging Comets . Springer, New York, 2011, ISBN 978-1-4419-6904-0 , pp. 43-44.

- ^ AG Pingré: Cométographie ou Traité historique et théorique des comètes . Tome II, Paris, 1784, pp. 52-55.

- ^ Stefan Krause: Comet McNaught (C / 2006 P1) . Bonn, 2013. ( PDF; 178 kB )

- ↑ C / 1743 X1 in the Small-Body Database of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (English).

- ↑ SOLEX 11.0 A. Vitagliano. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015 ; accessed on May 2, 2014 .