Carl Zeiss

Carl Zeiss , later also Carl Zeiss (born September 11, 1816 in Weimar , † December 3, 1888 in Jena ) was a German mechanic and entrepreneur . He founded the Carl Zeiss company .

Life

family

Carl Zeiss was born in Weimar on September 11, 1816, the fifth of twelve children, six of whom died early.

His mother Johanna Antoinette Friederike (1786–1856) was the youngest daughter of the court advocate Johann Heinrich Schmith, Stadt vogt von Buttstädt , a small district capital north of Weimar. Many lawyers and theologians can be found among their ancestors. To their ancestral community belonged u. a. Goethe's wife Christiane Vulpius , the doctor Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland , the poet Jean Paul and, in later generations, the painter Max Slevogt .

The father Johann Gottfried August Zeiß (1785–1849) came from Rastenberg , where the handcrafted father's ancestors had lived for over 100 years. From there he moved with his parents to Buttstädt, six kilometers away, and got married there. While his brother stayed on site and took over his father's workshop, August Zeiß went to Weimar, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Saxony-Weimar-Eisenach . Here he became a highly respected master turner who made mother-of-pearl, amber, ivory and other precious raw materials with z. Sometimes new machines were processed into luxury items that only rich people could afford. He came into contact with the Hereditary Prince and later Grand Duke Karl Friedrich (Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach) (1783-1853), the son and successor of Goethe's friend Karl August von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (1757-1828) . Since Karl Friedrich liked to be a craftsman and wanted to learn the art of turning, he looked for a suitable teacher and found him in August Zeiß. This led to a friendly relationship between the two that would last for 40 years.

When the aforementioned son was born to the Zeiss family on September 11, 1816, the Hereditary Prince took over the sponsorship and the newborn was baptized Carl Friedrich , the name of the heir to the throne. Of the siblings, three sisters and two brothers reached adulthood.

The spelling of the family name was not clearly defined during Carl Zeiss' lifetime. There are also Zeis, Zeyesz, Zeiss and Zeus . In order to put an end to this uncertainty, his son Roderich and Ernst Abbe did not agree on the Zeiss spelling for the company until around 1885 .

education

Because advancement in society was only possible through a better education, Father Zeiss sent his sons to high school. The two oldest then studied philology and history and devoted themselves to school service, where they received high honors. Carl, on the other hand, had a hernia and had to wear a hernia at all times. Therefore, in the father's opinion, he should, if possible, not sit down at his desk for long periods of time. He attended the Wilhelm-Ernst-Gymnasium Weimar only up to the penultimate grade. There he passed a special Abitur examination which allowed him to study certain subjects - primarily natural science - at a university. His interest in technical things was awakened early on, so that he was already attending lessons at the grand ducal trade school in Weimar while still at school and finally decided to become a mechanic.

Carl went to Jena , where he took up an apprenticeship with Friedrich Körner (1778-1847), the court mechanic and private lecturer at the University of Jena , at Easter 1834 . His teacher was known far beyond his place of residence and devices for Goethe were already being built and repaired in his workshop.

Zeiß stayed with Körner as an apprentice for four years and from the second year onwards was allowed to attend a mathematics or science lecture at the university. In addition, he had been a full student since May 1835 . math. enrolled, for which his leaving certificate from the Weimar high school gave him the authorization. In the winter semester of 1836/37 he joined the Academic Singing Association Paulus . Zeiß finished his apprenticeship in 1838 and received a benevolent evaluation from Körner as well as a leaving certificate from the university, which listed all the lectures he had attended.

It was the time when steam engines and locomotives were a great attraction for young people. So it is understandable that after completing his apprenticeship, Carl Zeiß initially devoted his special attention to mechanical engineering. He went on a journey that lasted from 1838 to 1845 and took him to Stuttgart , Darmstadt , Vienna and Berlin . While nothing more is known about his stay in Stuttgart, Zeiss seems to have worked for Hektor Rössler in Darmstadt. At that time, Vienna was considered the most important location for mechanical engineering in Central Europe. That is why Zeiß worked in the local machine factory of Rollé and Schwilqué in 1843. He also used his stay in Vienna to attend the lectures on popular mechanics at the technical department of the k. k. polytechnic institute to listen to. He took a final exam there, which he passed with distinction. Zeiss spent the last year of his wandering in Berlin with a mechanic. So he concentrated on the mechanics in a foreign country and only paid a marginal attention to the optics.

Establishment of a workshop for precision mechanics and optics

After long deliberations, Zeiß came to the conclusion that he would work again in his original subject, scientific apparatus engineering , and after the end of his years of wandering he would become self-employed as a mechanic. It is often said that Zeiss initially selected his hometown Weimar for this and that a corresponding application there was rejected with reference to two existing workshops and the lack of need for additional capacities. Today, this is considered improbable, but Zeiß consciously sought to be close to the Jena University and the botanist Matthias Jacob Schleiden , who had co-founded his interest in optics and also pointed out the need for high-quality microscopes. In addition, his brother Eduard had been running the Jena Citizens' School since 1842 and probably kept him up to date on developments in the city.

In order to realize his plan, however, he first needed a lot of patience with the bureaucracy at the time. Above all, a residence permit for the city was required. It was easiest to get by posing as a student. Zeiß enrolled at the university and since November 1845 attended mathematical and chemical lectures. He also worked as an intern in the private physiological institute founded by several professors and built various apparatus. At that time, there were already two relevant workshops in Jena, namely that of the mechanic Braunau (1810–1860), who had also learned from Körner, in addition to the Körnerschen.

Finally, on May 10, 1846, Zeiß addressed a request to the regional directorate in Weimar for a license to set up a mechanical studio in Jena. In it he refers to the increasing need for mechanical devices and justifies his wish for a branch in the city of Saale with the fact that the close connection with the sciences is important to him.

Despite the approval of respected professors from the University of Jena, Weimar took a lot of time to process the application. However, Zeiß not only had to wait a long time, but also had to undergo a prescribed examination by the grand ducal building authority, to which he was only invited in July and which he successfully passed in August. Given the sluggishness of the authorities, it was finally November when Zeiss finally held his license to manufacture and sell mechanical and optical instruments as well as to set up a workshop for mechanics in Jena . He also obtained local citizenship of Jena for a fee and after taking a solemn oath .

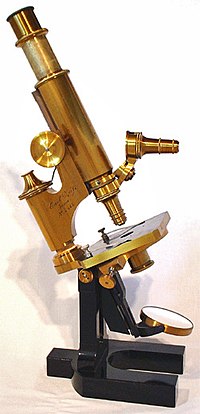

Zeiß opened his business on November 17, 1846 with start-up capital of 100 thalers , which his brother Eduard, who also lived in Jena, had advanced and was later reimbursed by father August Zeiß. Carl Zeiss initially worked alone, designing, building and repairing all kinds of physical and chemical instruments, of which the magnifying glasses , which he cut out of mirror glass , were particularly popular at the beginning. In addition, glasses, telescopes , microscopes, drawing tools , thermometers, barometers, scales, soldering tube accessories and other devices were sold in a small shop that Zeiß obtained from foreign manufacturers.

In 1847 he started producing simple microscopes , which soon turned out to be a very special bestseller. They held their own against the competition from Vincent Chevalier (Paris), Simon Plössl (Vienna) and even his teacher Körner because they were not only cheaper but also better. Because with the devices supplied by Zeiß, the focus was not adjusted by adjusting the object table, as with the competition, but by adjusting the column that carried the optics, which was particularly praised by the users.

Business started so well that an assistant could already be hired in the spring of 1847 and a larger workshop was moved into on July 1, 1847. In August 1847, Carl Zeiss took on his first apprentice, 17-year-old August Löber (1830–1912), who was to develop into the most important employee, especially in optics production, and who then shared in the profits. This year a total of 27 simple microscopes were delivered abroad, i.e. to customers who lived beyond the borders of the Grand Duchy. But the rapid rise was followed just as quickly by a crisis due to the bad harvests of 1845 and 1846, the trade crisis of 1847 and the revolution of 1848/49 . Despite these economic difficulties, Zeiß had acquired such a good reputation with his products within a few years that in 1850 the then Prussian University of Greifswald made him an interesting offer. The university mechanic Nobert there had moved to Barth , and in order to fill the gap that had arisen, several professors from the philosophical faculty asked Zeiss to take over the post of curator of the physical cabinet at a salary of 200 thalers. But nothing came of it, because the influential mathematician Johann August Grunert managed to ensure that the post in question was not filled by a "foreigner" like Zeiß, so that for better or worse he had to stay in Jena.

His sister Pauline initially took care of his household until Carl Zeiss married the eleven-year-old pastor's daughter Bertha Schatter (1827-1850) from Neunhofen an der Orla on May 29, 1849. However, his young wife died on February 23, 1850 giving birth to their first son Roderich, who survived and later worked in his father's company. Zeiß married a second time on May 17, 1853, namely Ottilie Trinkler (1819-1897), daughter of the rector and later pastor from Triptis , who was able to trace her family tree back to Martin Luther . The couple had a son (Karl Otto, 1854–1925) and two daughters (Hedwig, 1856–1935 and Sidonie, 1861–1920).

By the way, Zeiß lived very modestly and invested as much of the money he earned in his business. He made no fuss about himself, which led to the fact that he was sometimes underestimated and his importance for the company was not always fully appreciated (e.g. Auerbach, 1918). In his extremely limited free time, he developed into a bookworm. He also loved gardening and specialized in growing roses.

Carl Zeiss as an employer

Zeiss directed his workshop in a strictly patriarchal sense. He smashed microscopes with the hammer on the anvil himself, which his assistants had not made with the high precision he required. In such cases he refused to pay the wages to the assistant concerned, just as if the pace of work was too slow. Nevertheless, there was a good working atmosphere. The annual company outings by horse-drawn carriage and other festivities that Zeiß organized at the company's expense contributed to this. He also liked to invite his co-workers to his garden and treat them to wine and sandwiches. First of all, he asked new staff members to be hired into the living room and interviewed them extensively over a glass of wine.

The company worked from 6 a.m. to 7 p.m. If you calculate the breakfast break of 15 minutes and the lunch break of one hour, this results in a daily working time of 11 3/4 hours. As a top earner, Löber received three thalers a week for this in 1856, while another assistant had to be content with two and a half thalers. However, most of the assistants in the then still rural Jena owned at least a small garden. If there was a lot of work there, with the approval of the principal, you could stay away from the workshop for a day.

Improvement of the microscope

Initially, there was no division of labor in microscope production. Each assistant built his device from start to finish and the first models were therefore signed with the name of the person who made them. Only those items that would have taken a lot of time to produce, such as B. object tables were delivered prefabricated. Zeiß made the first approach to the division of labor in 1857 when he set up the optical department under Löber's direction and separated it from the mechanical department.

Each workshop naturally had its own special factory secrets, which it was extremely important for every owner, including Zeiss, to guard. Therefore, the most capable employees who had insight into these secrets, such as B. Löber, sworn to secrecy under a solemn oath.

Since the establishment of the company, the botanist Matthias Jacob Schleiden (1804–1881) was a constant advisor and sponsor and often spent hours in the workshop. He advised Zeiss to focus his production on microscopes, since these were suddenly in great demand with the cell theory, which was just blossoming at the time. In addition, as a co-founder of this theory, Schleiden himself had a personal interest in good microscopes. As a result, the simple microscope has been continuously improved. The frames of the lens systems received a flared edge at the bottom to protect the front lens against damage if the specimen was accidentally burped. That was u. a. Highly praised by the Darmstadt botanist and well-known microscopist Leopold Dippel (1827–1914) and copied by many other workshops. As far as the enlargements are concerned, a three-lens system with 200x (price: five thalers) and in 1856 another with 300x enlargement (8 thalers) came onto the market. Even higher magnifications, which were really useful for the user, were only provided by the assembled microscope and Zeiß now had to think about building them if he did not want to be overwhelmed by progress.

This required extensive preparatory work, which the far-sighted Zeiß had begun long before. Above all, he no longer wanted to manufacture the optics using the previously common method, namely probing. In this procedure, the lenses of one system were repeatedly replaced by others and their distances from one another changed until a usable optical system was achieved. This was then recreated according to the pattern developed through trial and error, or further improved by changing the lens radii and distances. Zeiß was more of a mechanic by nature, so he had not committed himself to the traditional opticians and was more easily accessible to innovations. Contrary to common practice, he now wanted to manufacture microscope optics based on calculations, which experts considered impossible for various reasons. Nevertheless, Joseph von Fraunhofer (1787–1826) had already built a telescope lens in Munich in 1819 based on a calculation and Josef Maximilian Petzval (1807–1891), an employee of Johann Friedrich Voigtländer (1779–1859), was in Vienna in 1840 for one Successful photographic lens. Zeiß first tried to acquire the theoretical knowledge necessary for this himself by studying books in the evening. Since he was unsuccessful, he turned to the mathematician Friedrich Wilhelm Barfuss, like his teacher Körner. This collaboration lasted from 1852 until the scientist's death, but remained fruitless. So Zeiß initially began building compound microscopes, using the two-lens lens of his simple microscopes as objectives that could be screwed to a tube and combined with eyepieces. These instruments were first offered in the 5th price list in 1858; however, Zeiss had already made the first in 1857.

After the previous university mechanic Braunau died in 1860, Zeiß applied for this position. He was less concerned with the title than with the license to teach, which was usually granted on this occasion, which made him a member of the university and guaranteed tax exemption. There were no problems with the appointment as a university mechanic, but the Senate was only able to come to terms with the much more important teaching authorization after some back and forth. Nevertheless, Zeiß was only happy about the tax exemption for two weeks. Then a law was found according to which this privilege should only apply to those people who earned their living exclusively from teaching and writing. As a trader, Zeiß was of course not part of this group. But other awards followed, namely a silver commemorative coin at the 1st General Thuringian Trade Exhibition in Weimar for his "excellent microscopes with auxiliary devices" and a first honorary award at the 2nd Thuringian Trade Exhibition in 1861. In 1863, Zeiß was appointed court mechanic.

In the meantime, the economic difficulties had been overcome and the company had expanded so much that in 1858 a new, larger workshop had to be moved into, which was finally located in its own, bought property. Zeiß was now in business relationship with many, partly well-known companies, such as B. with Julius Kern in Aarau (Switzerland), Emil Busch in Rathenow (supplier of glasses) and WC Heraeus in Hanau (supplier of platinum). From 1861 there was a description of how Zeiß dealt with one of his customers: When the still insignificant zoologist Ernst Häckel (1834-1919), who was working as a poorly paid private lecturer at the University of Jena, came to Zeiß and asked for a simple microscope that was supposed to be cheap, Zeiss understood the academic, made him a good price and even added a magnifying glass.

The composite microscopes improvised from the optics of the simple microscopes and eyepieces could not convince in the long run, although they were praised by Schleiden. That is why the newly designed compound microscopes appeared for the first time in five different versions in the 7th price list from August 1861. The largest of these was a horseshoe tripod, as had been built by the well-known microscope manufacturer Georg Oberhäuser in Paris and cost 55 thalers. On the underside of the object table it was provided with a curved screen designed by Zeiss and had a mirror for setting inclined lighting, which could not only be swiveled sideways but also forwards. Zeiß calculated the tripod, lenses and eyepieces individually for his customers so that everyone could put together the optics combination that was convenient for them.

Once the composite microscopes were available, their advantages over the simple ones became so evident, especially with the higher magnifications, that Zeiß gradually stopped producing the more powerful systems for his simple microscopes (the 300-fold triplet as early as 1863, the 200th -fold 1866 and 120-fold doublet 1886).

The lenses belonging to the new compound microscopes were still tried and tested, but still met with immediate approval. Leopold Dippel took a closer look at the quality of the most used lenses, labeled A, C, D and F, and praised them very much. (Dippel, 1867, p. 188). Edmund Hartnack had taken over the business of his uncle Oberhäuser and Zeiss knew very well that he could not achieve the quality of Hartnack's water immersions with his strongest lens . All attempts to improve this condition through probing have failed.

Cooperation with Ernst Abbe

Then Zeiß took up his old idea again and wanted to manufacture the lenses on a mathematical basis. He looked for a helper again and this time chose the physicist Ernst Abbe (1840–1905), who worked as a private lecturer in Jena. The collaboration between the then 50-year-old Zeiß and the 26-year-old Abbe began on July 3, 1866, and the goal was to create a water immersion that should have the same imaging properties as Hartnack's. But before that could be tackled, the optics production had to be modernized, which could not be done without resistance from Löber and the other assistants, who preferred to stick to the traditional. Before assembling a lens system, the properties of all individual lenses should be carefully checked, which led to more efficient production. Löber had already done preliminary work with the test glass he had invented for testing lens surfaces using Newton rings . Fraunhofer had come up with the same solution long before that, but none of it got through to Jena. Abbe constructed a number of other measuring instruments, e.g. B. for measuring focal lengths and refractive indices . The result of all these efforts was available in 1869. Outwardly, the microscopes had hardly changed, but because of the more rational production, more microscope objectives could be produced with the same staff, so that their price fell by 25%.

Now Abbe got down to his real task, namely calculating the lenses. He received every possible support from Zeiß and, as an employee, the most capable person from the optical workshop, namely August Löber. Nevertheless, there were still many difficulties to be overcome before the work was finally done in 1872. Catalog No. 19 on microscopes and microscopic auxiliary devices says: “The microscope systems listed here have all recently been constructed on the basis of theoretical calculations by Professor Abbe in Jena.” Their quality has now been exceeded by any competitor product. This was also reflected in the price: while the best microscope still cost 127 thalers in 1871, in 1872 the top model had to pay 387 thalers, i.e. 1161 marks. Nevertheless, the orders did not stop and at a meeting of naturalists and doctors in Leipzig the new lenses received high praise.

The microscope production had meanwhile been further modernized. But Abbe still struggled to fully enforce the division of labor against opposition from a large section of the workforce, and even in 1874 he had not yet fully succeeded in doing so. Zeiß initially rewarded Abbe for his success with a generous profit share and even took him on as a partner in 1875. But in addition to a financial contribution, Abbe had to undertake not to expand his activities at the university. The optical calculations were expressly considered company property and were not allowed to be published, which contradicted Abbe's original plans.

The Zeiss health insurance company was founded in 1875. In the event of illness, it guaranteed every employee free treatment by a statutory health insurance doctor as well as the free purchase of medicines. In the event of incapacity for work, financial support was paid for six weeks and half of that for a further six weeks. After work, the staff members cultivated various forms of socializing. One met z. B. in the so-called knot band in a wet and happy round. In addition, books were procured for further training, from which the mechanics library developed over time.

On October 14, 1876 the completion of the 3,000th microscope could be celebrated and the workforce had meanwhile increased to 60. In the same year, his son Roderich joined the company, took over commercial and administrative matters and became a partner in 1879. He also made a great contribution to the development of microphotographic apparatus. The modernization and expansion of the company was particularly driven by Abbe. Zeiß initially acted rather cautiously in this respect because he feared setbacks, some of which he had experienced in the course of his life. Nevertheless, at the beginning of the 1980s, with the approval of Zeiß, the transition to large-scale operation was initiated.

Zeiß was initially the main managing director and absolutely wanted to keep his stake in the company, which he still had after Abbe's entry, in family ownership. Over time, however, he subordinated himself more and more to Abbe's initiative and sometimes feared that the ever-expanding work might eventually grow over his head. Nevertheless, he was still active in the plant every day and in 1880 the philosophy faculty of the University of Jena awarded him the Dr. phil. H. c. The application was submitted by the zoologist Häckel, who in the meantime had risen to become professor and dean of the faculty.

The year 1883 reported that business was particularly strong. The new catalog no. 26 is a bound, representative book of 80 pages with 33 illustrations. It was printed in an edition of 5000 copies and the work cost three to four silver groschen each. However, the frugal period meant that part of these costs had to be borne by the resellers. Of these, one named Baker was particularly active in London. He often took off 40 or more lenses at once. In addition, our own field offices have been set up at home and abroad.

After it was possible to build microscope objectives on a mathematical basis, one problem remained, namely the production of suitable optical glass. So far it had been obtained from England, France and Switzerland and had to complain about poor quality, little choice and delays in delivery. So it seemed worthwhile to take the production of the optical glass into your own hands. It was therefore very convenient for Abbe that the chemist and glass specialist Otto Schott (1851–1935) from Witten sought contact with him in 1879. In 1882 Schott was persuaded to move to Jena, where the Zeiss works set up a glass technology laboratory for him with government support. Here new optical glasses were first developed and their production started later. From this laboratory, the Jena glassworks Schott and comrades arose, in which, in addition to Schott himself, Carl and Roderich Zeiss and Abbe were involved, today's Schott AG .

Old age and death

In December 1885, Zeiß suffered a minor stroke, from which he recovered. The Grand Duke awarded him the Order of the White Falcon on his 70th birthday . In the same year, i.e. 1886, the apochromatic microscope objectives came onto the market. They represented the culmination of the efforts, inspired by Zeiss and carried out by Abbe, to create lenses on a computational basis and delivered an image quality previously unknown. The members of the Congress of Russian Doctors were so enthusiastic about it that they made Zeiss an honorary member the following year. Zeiß attended the celebration on the occasion of the completion of the 10,000. Microscope on September 24, 1886, to which all employees and their wives were invited. It was a lavish festival that people in Jena talked about for decades. Then Zeiss began to lose strength quickly. After several strokes in the last quarter of 1888, he died on December 3, 1888.

When assessing the work of Carl Zeiss, one has to state that although he introduced some improvements to the microscope, he did not invent anything fundamentally new himself. However, it was important that he always paid attention to the utmost precision in the devices manufactured by himself and his employees and that he sought contact from the outset with scientists who were useful to him and who gave him valuable tips for the construction of his microscopes.

The greatest achievement of Zeiss, however, is that he stuck to the idea of manufacturing microscope objectives on a mathematical basis, even when his own efforts and those of Barfuss failed. If this task was finally solved by Abbe and not by himself, then Zeiß has to be credited for having awakened Abbe's interest in the optical calculation and for having given him every possible material support. The manufacture of the lenses on the basis of calculations was only possible with skilled workers who had learned to work with the utmost precision, which Zeiß had always attached the greatest importance to. But another thing was important, namely the internal reorganization and the change from the workshop to a large company. This made it possible to build microscopes in large numbers with high precision. Abbe was initially the driving force behind this development, but Zeiß ultimately affirmed and supported it. Competitive companies that did not understand the introduction of the calculated optics and the transition to large-scale operations were doomed to failure.

Ernst Abbe paid tribute to Carl Zeiss in several speeches and set him a permanent memorial through the Carl Zeiss Foundation established in 1889 .

Honors

- Two schools were named after him: The Carl-Zeiss-Oberschule in Berlin and the Carl-Zeiss-Gymnasium in Jena .

- The Carl Zeiss Foundation received his name in 1888.

- Several streets were named after him a. a. in Bremen , Dresden, Jena, Erfurt, Mainz and Heilbronn.

- The soccer club FC Carl Zeiss Jena is named after him.

literature

- Gustav Emil Lothholz: Zeiss, Karl . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 45, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1900, pp. 5-7.

- Felix Auerbach: Ernst Abbe. His life, his work, his personality according to the sources and from his own experience. Academic Publishing Society, Leipzig 1918.

- L. Dippel: The microscope and its application . First part: Construction, properties, testing, current condition, use (general), etc. Vieweg, Braunschweig 1867.

- PG Esche: Carl Zeiss: Life and Work , Jena City Museum, Jena 1966.

- Wolfgang Gloede: From reading stone to electron microscope. VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-341-00104-2 .

- Moritz von Rohr : On the history of the Zeissische Werkstätte up to the death of Ernst Abbe. With contributions by Max Fischer and August Köhler. Volckmar, Leipzig 1936.

- Friedrich Schomerus: History of the Jena Zeisswerk. 1846-1946 . Piscator, Stuttgart 1952.

- H. Volkmann: Carl Zeiss and Ernst Abbe. Your life and your work. In: Deutsches Museum, Treatises and Reports. 34th year, issue 2. Oldenbourg, Munich 1966.

- Horst Alexander Willam: Carl Zeiss 1816–1888 , in: Tradition , 6th booklet. Bruckmann, Munich 1967 OCLC 3518141 .

- F. Zeiss, H. Friess: Carl Zeiss and his family. A collection of genetic facts, published on the occasion of the 150th birthday of the plant founder. Starke, Limburg 1966.

- Erich Zeiss , Friedrich Zeiss: Court and University Mechanics Dr. H. c. Carl Zeiss, the founder of the optical workshop in Jena. A biographical study from the perspective of his time and his relatives. Clan association of the Zeiß family, 1966, no details.

- Rüdiger Stolz, Joachim Wittig, Günter Schmidt: Carl Zeiss and Ernst Abbe: Life, Work and Meaning; Scientific historical treatise , Universitätsverlag, Jena 1993, ISBN 3-925978-14-3 .

- Rolf Walter, Wolfgang Mühlfriedel (Ed.): Carl Zeiss. History of a company , Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 1996–2004:

- Volume 1: Edith Hellmuth, Wolfgang Mühlfriedel: Zeiss 1846–1905. From a workshop for mechanics to a leading company in optical device construction. 1996, ISBN 3-412-05696-0 .

- Volume 2: Rolf Walter: Karl Zeiss Zeiss 1905–1945 , 2000, ISBN 3-412-11096-5 .

- Volume 3: Edith Hellmuth, Wolfgang Mühlfriedel: Carl Zeiss in Jena 1945–1990 , 2004, ISBN 3-412-11196-1 .

- Stephan Paetrow, Wolfgang Wimmer: Carl Zeiss: a biography: 1816–1888 , published by the Zeiss Archive, Carl Zeiss AG, Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-412-50387-1 .

Web links

- Biography of Carl Zeiss on the Carl Zeiss AG homepage

- First simple microscope from Carl Zeiss from 1847/1848

- Literature by and about Carl Zeiss in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Carl Zeiss in the German Digital Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ General directory of members 1828–2003 . Published by the Association of Old Men of the Landsmannschaft in the CC Rhenania zu Jena and Marburg, 2003.

- ↑ Michael Baar: Before the 200th birthday comes the end of the Carl Zeiss legend. In: Thuringian General . September 8, 2016, accessed September 10, 2016 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Zeiss, Carl |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German mechanic and entrepreneur |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 11, 1816 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Weimar |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 3, 1888 |

| Place of death | Jena |