Decors of Chinese ritual bronzes

The decors Chinese ritual bronzes are a number of periodicals of jewelery and surfaces ornaments based on the heterogeneous group of Chinese ritual bronzes emerge (Chinese: 青銅器 Bronze subject, bronze artifact ). Some of these design elements form a kind of standard repertoire, while other elements only appear sporadically.

Individual decors are not limited to certain types of ritual bronze. In principle, any type of decor can appear on any type of object. Most of the motifs and decors have forerunner forms in earlier ceramic or jade objects that can be traced back to the fourth millennium BC .

Bronze objects in China can, in addition to their classification into object types, also be grouped regionally or chronologically based on their decors. Therefore a rough categorization according to historical and cultural-spatial aspects takes place here. The rule is a decoration in relief that was cast with the bronze object. This type of decorating technique is what is meant below, unless other techniques or materials are mentioned.

From the beginnings of the Bronze Age to the western Zhou period in the cultural area of the North China Plain

The North China Plain , together with the Central China Plain, forms the heartland of China and is often referred to as the "cradle of Chinese culture". This is where the urban centers of the semi-mythological Xia Dynasty , the Shang Dynasty and the Zhou Dynasty were : Erlitou , Luoyang , Erligang ( Zhengzhou ), Yinxu , Fenghuangshan and Feng-Hao . These dynasties did not dominate the whole territory, but were on the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River , and located adjacent areas, and they drove trade with neighboring peoples and cultures, including long-distance trade.

Overall, the culture of the dominant ruling clan in this area was consolidated, so that a continuity can be seen, based on which individual periods are summarized. The advancing expansion of the sphere of influence extended the sphere of influence to the south, up to today's Hunan Province . In large parts, the culture of the heartland superimposed that of the neighboring regions, but did not fully assimilate them. Of the six great cultural areas of the Chinese Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age, all survived into the Warring States' times .

Representations of people, masks and faces

The most common mask or face decoration is the taotie (Fig. 1). It is the representation of two eyes that are arranged around a central axis and form the obligatory part of the taotie . This is very simple in the early development phases. Later, other parts of the face and body are added to the eye spots, so that the representation becomes more complex and differentiated. This development was completed by the Anyang phase (13th - 11th century BC) of the Shang period.

Jaws or fangs, large, C-shaped horns and ears, which form the head, as well as rudimentary forelegs or claws and an abdomen with a tail are added to the eye-spots. The origin of the taotie decoration remains unclear for the time being. It has been speculated on various occasions that anthropomorphic representations on the cong of the Liangzhu culture or similar decorative bronze plaques with turquoise inlays from the Erlitou culture could be considered as precursors of the taotie representations. The term taotie is ahistorical. In connection with ritual bronzes, it appears for the first time late, at the end of the Warring States Period :

- Lüshi Chunqiu , Chapter 85 / Role: Knowledge of the foregoing.

- 周 鼎 著 饕餮 , 有 首 無 身 , 食 人 未 咽 , 害 及其 身 身 以 以 言 報 更 也。

- The ding of Zhou are taotie engraved. They have a head, but they have no body, they eat a person without swallowing and directly damage the body, [so] it was reported by storytelling.

Different representations of human faces, some more, some less abstract, appear. These can show a relaxed, undifferentiated facial expression , but in some examples they are shown laughing maliciously or showing teeth. A mixture with theriomorphic elements is not uncommon. A well-known example from Hunan shows a very naturalistic face with relaxed facial expressions, which, however, has the typical C-shaped horns of the taotie , as well as its claws and a tail (Fig. 2).

There are depictions of faces with deer antlers and a few examples showing heads or faces in scenes of eating or devouring. Often the head is arranged symmetrically in the middle , on the sides of which are two big cats , which open their mouths towards the head. Depictions of whole people in scenes are rarer, although the structure is the same with the “victim” of the act of eating in the middle, surrounded by two predators with open mouths. A sculpture vessel depicting a tiger threatening to devour a person has also been found in Hunan (Fig. 3). Usually, however, depictions of people, masks and faces are surface decorations worked in relief. These are regularly openwork on ax blades .

Dragons and snakes

Dragons and snakes have been part of the decor repertoire of the Chinese cultural area since the Neolithic . The earliest documented dragon representation is from the middle of the fourth millennium BC. Dated. They are arch-shaped jade objects from the Hongshan culture , which are called pig kites. In the Shang and Zhou period bronzes, dragons or dragon-like hybrid creatures appear in different forms.

The best known and most common form is the kui dragon (Fig. 4). It consists of a reptilian head, followed by a long, snake-like body. An important characteristic of the kui dragon is a single leg that supports its body. The dragon-like hybrid beings also include the bird dragon , which has a beak that is often short and curved, like that of a bird of prey. It represents a later form of dragon decorations and appears from the Shang period. The kui and bird kites can be found as a relief on the object surfaces. However, there are also vessels with legs that can be shaped like kui dragons or dragon-like chimeras. The tails form the feet or standing surfaces, while the heads - with their mouths opened - are attached to the body of the vessel. The use as surface decoration worked in relief is the rule.

The last of these decors is the one-headed dragon with two bodies, which appeared from the Erlitou culture and was preserved until the Zhou period. A head aligned frontally forms the center of the representation and on both sides a mostly snake-shaped body runs outwards in an exactly mirrored form. Because of this reflection, it is unclear whether there are two bodies on one head or just an "unfolded", stylized body, as in the taotie . Another type of dragon appears on the handles of the bronze vessels. These have a broad, flat nose with two nostrils that are visible from the front and are reminiscent of the already mentioned pig kites of the Hongshan culture. There is no equivalent for them in the surface decorations.

On some of the vessels there are further animal heads, some of which are reminiscent of dragons, which cannot be identified in more detail, stepping out of the vessel. These often have mushroom-shaped horns, which make classification into the group of mythological beings such as dragons more likely than classification into the categories of ordinary animals. Dragon-like creatures also appear as handles on the lids of Zun or gong , which are often reminiscent of salamanders or crocodiles and can also have mushroom-shaped horns.

Birds

The depictions of birds form a large group , beginning in the Shang period, as surface decoration in relief or as sculpture vessels. During the Zhou period, they became increasingly important and common. A distinction can be made between different categories of birds, for example diurnal birds of prey, owls , hens and hybrids with a bird-like character or parts of birds (Fig. 5).

The symbolic meaning of these birds is varied and not entirely clear. What is certain is that the Shang venerated birds and attribute their progenitor to a bird, although it is disputed whether it is a swallow or a raven or a crow. The myth of the ancestry of a Shang bird would explain the appearance of bird decorations on their ritual vessels. However, these representations are so strongly stylized that they cannot be identified in more detail and cannot contribute to the controversy about the identity of the Shang ancestor.

A clear distinction must be made between the diurnal birds of prey and the owls. While the former stand out due to their striking bird of prey beaks, depictions of owls can be distinguished from the other birds by their rounded shapes and large eyes. The situation with the birds of prey is similar to that with the other birds: Due to the high level of abstraction , it is not possible to distinguish between falcons , eagles and buzzards (Fig. 6). The owls in particular appear as sculpture vessels or form one of the constituent parts of such a sculpture vessel. During the Zhou period, birds appeared as decorative elements in the ritual bronzes. This may be related to the fact that an omen in the shape of a red bird heralded the fall of the Shang and the Zhou takeover.

- Lüshi Chunqiu , Chapter 13 / Role: Contemplation of the beginnings.

- 及 文王 之 時 , 天 先見 火 , 赤 烏 銜 丹 書 集 於 周 社 , 文 王曰 「火氣 勝」 , 火氣 勝 勝 故 故 其 色 尚 赤 , 其事 則 火。 代 火 者 必將 水 , [...]

- When the time of King Wen [the Zhou] came, the sky showed a fire [sign]; the red bird held the vermilion scroll in its beak and sat down on the earth altar of the Zhou and King Wen said: "The energy of fire is victorious!" And because the energy of fire was victorious, he preferred the color red and based his actions on the [behavior of] fire. What the fire will overcome will be the water [...]

Horned animals

A multitude of horned animals appear as decorative elements on ritual bronzes. However, due to the high degree of abstraction, it is often difficult or even impossible to determine this more precisely and to assign it to an exact animal species. The horns or their shape are an important aid to identification , antelopes , rams , goats and deer can be identified.

Animals are most likely to be identified in sculpture vessels because of the more naturalistic representation. It is noticeable that rams, cattle (Fig. 7), goats and the like do not appear as surface decoration in the relief, but are always sculptural and stand out from the silhouette of the actual object. They can be decorative attachments on sculpture vessels or form handles, purchases or handles on them. In addition, they often appear on the shoulders of vessels, for example zu or lei , although they have been sculpted but integrated into the surrounding surface decoration . Furthermore, they can also be sculpted in the form of eye loops. In addition to the various horns it must be noted that they are sometimes used in hybrid creatures (Fig. 5).

Big cats

Big cats regularly appear in the form of sculptured vessels or as surface decorations under the ritual bronzes. Tigers are often referred to, although the identification of the cats is not clear in most cases. In addition to the tiger, there were and are other big cats in China, such as the leopard , which is also highly valued. Nevertheless, representations of big cats, which are clearly supposed to be images of tigers, are known. These big cat decors have stripes worked in relief, which specifically distinguish them as tigers. The depiction of big cats in motifs of eating is particularly to be emphasized, since explicit feeding acts in almost all cases have big cats as eaters. The few different cases are dragon-like mythical creatures. The elaboration of the motif can vary slightly.

Particularly well-known and archetypal is a gong from Hunan, which shows a tiger on the front, bending over a crouched person with its mouth open (Fig. 3). Both the complete elaboration of a naturalistic person, as well as the dynamic in which the impending act of eating is represented, are rare, if not unique, in the bronze art of the Shanghai period. The motif of eating also appears in relief, for example on the ritual axes of the yue type . The rule is formed by depictions of the motif with a stylized person or a human face or head in the middle and two big cats flanking them with open mouths from left and right.

Miscellaneous, unusual and exotic

In addition to mythological creatures such as dragons or phoenixes, other real animals appear that appear unusual or special. One of these animals is the cicada , which is the only insect in the decorative repertoire of the ritual bronze and is often encountered. Cicada decors can be found on all types of objects and can decorate various places. Because of their elongated shape, they are preferably found on the legs of vessels such as the ding or on the bodies of elongated vessels such as the gu . In most cases, they are shown vertical, with their heads up.

There are two varieties of cicadas: The first is the wingless cicada with an elongated, pointed abdomen and a rounded head with two relatively large eyes. The second looks similar to this one and has a similar structure, but it has wings and is therefore also known as a winged cicada. The wings are shown in greatly simplified form and mostly simple, T-shaped outgrowths that extend over the entire length of the cicada body.

Another animal that appears less often is the bat . She is shown with outspread wings, sometimes upside down. However, the identification of some decors as a bat is not without controversy. Often it seems as if they are variants of a taotie or mixed forms (Fig. 8; on the roof-shaped lid knob).

Elephants and rhinos were common in southern China until the Bronze Age . Even if their distribution areas were outside of the Shang rulership, they were known and used as decors. However, depictions of rhinos are rare, elephants appear more frequently, both as sculptural vessels and in relief as surface decoration (Fig. 9).

Aquatic animals rarely shown include fish and turtles . The latter rarely appear as decor and then in relief on object surfaces. Fish, on the other hand, are also represented vividly and, like kui dragons and birds of prey, are found as the legs of vessels that were used to warm the contents. As with almost all more naturalistic animal depictions, it can be stated that their frequency increases towards the periphery of the area of influence of the Shang and Zhou, with aquatic animals and exotic animals more towards the south, with horned animals such as rams or the like to the north and south.

The absence of floral elements such as leaves or flowers is remarkable . Instead, mushrooms or mushroom-shaped attachments appear on the lips of jue or jia (Fig. 10). Likewise, the horns of dragons or dragon-like creatures can be sculpted in the shape of a mushroom.

Geometric figures and patterns

In general, the decors of the Chinese ritual bronzes are composed of a reduced repertoire of basic building blocks. The dominant feature is the straight line, which in almost all cases runs horizontally or vertically and bends at right angles. The few exceptions include the lines from which the cicada decors are built up, which taper towards the abdomen at an acute angle, or the generally rounded components in animal or animal-like decors, such as the eyes of the taotie or the heads of the cicadas. The tendency to straight lines and the renouncement of round elements not only run through the decors, but also through the decor zone structure of the objects.

Decorative zones, decorative strips and individual decorative components always have a rectangular or square shape. This tendency in the bronze decors is very similar to the standardization and formalization of the Chinese script , which was also transformed from the more naturalistic, dynamic pictograms of the oracle bone inscriptions into the more rigid and “angular” forms of the seal script . Overall, the small ornaments are more flexible than the structuring of the decors in zones and the decors themselves, it also allows for more rounded shapes.

Leiwen

The Leiwen 雷 文 is an almost ubiquitous small surface decoration, which is referred to in the specialist literature as a background pattern. In fact, one cannot speak of a background because the bronze decors are flat. The Leiwen fills surfaces, regardless of whether they are within other, larger decorative elements or whether these are spaces between the decorative elements. All Leiwen have in common that they are spiral-shaped, whereby the spiral shape is not round, but angular.

Not all of these surface decors are identical to one another. Different vessels or bells carry the pattern in different designs, and it can also appear in variants within an object. The variance is comparable to writing styles or the distinction between normal, bold and italic fonts. The spirals are always uniform within individual surfaces. Presumably, it was a deliberate design element in order to create contrasting elements and surfaces of different decor. The name Leiwen means "thunder pattern" or "thunderstorm pattern" (Fig. 4).

Vortex circles

The vortex circle is a rare, round, small ornament. It consists of a single or double border - usually cast raised - and can have a point or a simple small ring in the middle. From the border inwards, C- or J-shaped curves point clockwise or counterclockwise, which give the impression of dynamism and rotation (Fig. 10).

Monoculi

Monoculi are eye spots that are either round like natural eyes or stylized and slightly angular. For the most part, they look a lot like Taotie's eyes . In contrast to these, they are not integrated into a face or mask decoration. As a rule, they appear in decorative tapes on vessels, which run horizontally and mostly around the neck of the vessel.

Pins or nipples

Small, roughly hemispherical nipples appear especially on the surfaces of bells. These are flat and undecorated or they show a jagged, angular crack pattern that converges towards the tips, giving the impression that they are images of small mountains. In the western Zhou period, this decorative element was further developed: the original, flat nipples become long thorns or pins, some of which protrude several centimeters from the bell's body. The Chinese technical term for these nipples is 枚 méi, meaning “ little button”. From the western Zhou period, such small, hemispherical nipples also appeared on vessels.

Lines, ridges, ridges

Individual decorative ribbons or decorative surfaces are separated by single or double lines, sometimes also ribbons. In addition, the burrs that arise between the molded parts during casting can be worked out as raised webs or elaborate decorative burrs. These separate decorative zones from one another or form the central axis in a symmetrically mirrored decor, such as animal pairs or two halves of a taotie (Fig. 1). Decorative ridges can be made simple and only have a segmentation as decoration. During the Zhou period, there was a tendency towards increasingly complex decorative ridges, some of which are reminiscent of scales, fins or wall battlements. In general, the richness of shape and the three-dimensionality of the decorative ridges increased sharply at this time (Fig. 8).

Rhombuses

Rhombuses rarely appear in decors that favor horizontal and vertical elements. These are placed next to each other as decorative strips along the vessel bodies. They never stand alone. The delimited area is filled with leiwen , which is often stretched to visually underline the diamond shape. The center of the rhombuses is often accentuated by a hemispherical nipple cast in relief.

Inlay work

Although the technique of pickling was well known and did not present a technical challenge that could not have been mastered, the Shang and the Zhou largely avoided it. In the periphery, however, for example in Sichuan , bronze plaques with inlays made of semiprecious stones were made as early as the 12th century BC. Turquoise was used in the west as well as with cultures from the north. Typical found objects from the Chinese mainland which have inlays are the decorated with turquoise jewelry plaques of Erlitou culture, a great similarity with the taotie have -Dekoren the Shang. However, these techniques were hardly adopted by the Shang, only a few ritual bronzes from that time with turquoise inlays are known. Most of these are weapons (Fig. 11).

Eastern Zhou Period

With the end of the centralization of power under the Zhou kings, the feudal princes gradually became independent, raised their own armies and assumed the title 王 , i.e. king, which until then had been reserved for the rulers of the Zhou alone. This development began in the spring and autumn periods and finally culminated in the time of the Warring States . In the course of the fragmentation, bronze casting developed differently, in particular in terms of marginality, which was less close to the culture of the heartland, or the sub-rich took on foreign influences more easily, especially in the north, where the art of the steppe peoples partly left strong traces in bronze casting. These processes are complex and multi-layered, so that the facts should only be shown using exemplary found objects.

General tendencies

With the decline of the central kingship and the emergence of small states that emerged after the Zhou capital was moved to Luoyang , the Chinese heartland entered a phase of competition between various feudal princes, which began in the early fifth century BC. Chr. In constant war among them led to changing alliances . Despite the political instability, there were profound developments in society. Philosophy flourished and the feudal princes began to commission ritual bronzes to suit their tastes, so that after the normative influences of the strong central powers of the Shang and the Zhou, a radiation of forms and diversity of techniques and materials set in. This is based on the six large cultural areas mentioned at the beginning, which can be identified as follows in the East Zhou period:

- the Jin culture in the north and northwest, named for the state of Jin , includes Jin, Zhou, and Zhao

- the Qin culture in the northwest and west, named after the state of Qin , includes Qin

- the Chu culture in the south and southeast, named after the state of Chu , includes Chu and partly Ba

- the Qi culture in the east, named after the state of Qi , includes Qi and Lu

- the Yan culture in the northeast, named after Yan state , includes Yan

- the Wu-Yue culture in the southeast, named after the states of Wu and Yue , includes Wu and the Yue clans

Since the Neolithic, the northern outskirts of China have been a contact zone for settled and arable and livestock farming peoples, which in the broader sense belonged to “Chinese” ethnic groups, semi-nomadic cattle breeders who farmed the steppes with their herds and non-sedentary hunter-gatherer societies. In addition to the very different economic bases, the population of the region also consisted of different ethnic groups with different beliefs and material cultures, such as Indo-European, Proto-Turkish, Proto-Mongolian and Tungusian peoples.

In the south, the Chinese-influenced state of Chu developed into a major regional power. Its expansion ensured the enrichment of its own culture through takeovers from local cultures and triggered a displacement of other ethnic groups to the south and west. The Shu culture in Sichuan retained its extensive independence into the third century BC.

During the eastern Zhou period, a move towards more naturalistic, dynamic and lively animal representations can be observed. The rigidity and one-dimensionality of the image repertoire of the Shang and the Zhou are abandoned. Instead, concrete image motifs prevail and the abstract symbolism is replaced by a certain motif up to a narrative of the decors. Animal fighting and hunting scenes gain in importance under the influence of the northern nomadic peoples. From the south, from the region in Hunan, which used to be more inclined to naturalism, vivid depictions of animals prevail.

Furthermore, representations of people and anthropomorphic deities find their way into bronze art. Finds from Yue show people who, similar to Greek depictions of the Atlantic, function as feet for bronze sacrificial tables or altars. Anthropomorphic depictions of gods are known from Chu. In addition to these motivic representations, narrative representations develop that show a broad spectrum of social activities, such as hunting, dances, rites, playing instruments, agriculture, war scenes and the like.

The range of materials and finishing techniques also increased. Different metals and alloys, minerals and semi-precious stones were used to apply the inlay technique, which was again fashionable from the 6th century BC. A significant change is taking place with regard to the characters: While they were previously used as clan symbols, dedicatory inscriptions or for historiographical purposes, a decorative function of the writing can be recognized in the lavishly inscribed swords of Chu and Yue. The technique of fire gilding , which was used excessively by the northern steppe peoples to refine their everyday objects and bronze jewelry, gained in importance in China.

The bronze works of the south: the states of Chu and Yue

According to official historiography, Chu was established in the late 11th century BC. Chr. As a dependent of the Zhou state established. It gained nominal independence in the late seventh century BC. Chr. By assuming the title of king 王 by Xiongtong, who reigned as King Wu of Chu and understood par with the adoption of this Title, the Zhou. In fact, the Zhou had given up their ambitions in the south much earlier and Chu enjoyed a pronounced freedom that manifested itself in an independent cultural development.

To the southeast of Chu was the state of Yue, which was in constant competition with Chu and another state, Wu. Even if in large parts the bronze art of Chu and Yue followed that of the Zhou, there were some peculiarities and deviations. The Yue's technically extremely high-quality weapon smiths are known, which not only produced swords that are still sharp after more than 2300 years, but also stand out for their artful decorations in the form of gold inlays. These gold inlays, which were often used for characters, were also found in everyday objects such as bronze passes from Chu.

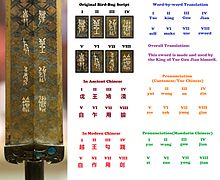

Up to the time of the Warring States, characters on ritual bronzes served more practical purposes, for example as dedicatory inscriptions or to record political events. The gold-inlaid characters on the pompous swords of the Yue, which clearly had a ritual or representative function, indicate a change in the way the characters are viewed not only as information carriers, but also as a design element. This would also be supported by the excessive use of a decorative writing form typical of the southern states, the bird-worm script , which was regularly used in Chu, Wu and Yue for decorative purposes on artefacts of various materials.

In general, gold leaf or other metal leaf alloys were widely used in Chu from the sixth century BC . It seems that a color-contrasting design of the surface was preferred. Gold leaf, silver leaf and other metals have been found at various sites in Henan, Hubei and Anhui. Metal inlays were from the 6th century. v. More often. This was copper, with the inlays pre-cast and then poured into the actual object. Inlay work, in which metals were hammered into recesses on the substrate, came about later.

In general, one can say about the bronze works by Chu, especially about vessels, bells and table or altar-like objects, that these often have a three-dimensional surface decoration and expansive applications. Decorative ridges in abstract or animal shapes are elaborate and expansive. The decorations of the bronze vessels of the Yue reflect the habit of settling on rivers. Although vessel types from the heartland clearly served as templates for their vessels, they often show animals associated with the water, such as snakes or frogs, both of which were rarely depicted in the heartland.

Tigers play a special role among animal representations. In the southern regions, i.e. in the state of Chu, but also especially in the state of Ba, which was displaced by Chu to the west in the direction of Chongqing , they are among the most common depictions of animals. Bells of the chunyu type , which differ from the typical Chinese bells of the Bronze Age by their almost round cross-section, appear mainly here and in all cases have an eyelet for suspension on the ceiling plate, which is sculpted in the shape of a tiger. The identification is always given because the characteristic stripe pattern is worked out in the relief. Apart from that, there are also few examples of such bells that show a tiger carved in relief on the bell body.

Some of these chunyu also show signs or symbols of unknown meaning or function on the ceiling panel . The characters have a pictographic character and are reminiscent of fish or crabs, while others are abstract. It is not clear whether this is a local script or just ornamental, as a local variant of the Chinese script was usually used.

Liyu bronzes and the bronze art of Jin and his successor states

A special form in the heartland of China are the so-called Liyu bronzes, which are named after the village of the same name Liyu bilden 峪 in Shanxi . Their style emerged from the sixth century BC and is a regional peculiarity. After the disintegration of Jins in 453, the style changed significantly. Its distribution is limited to the Jin State area.

The Liyu style is characterized by a strong abstraction of the decors, which consist of kui dragons or similar hybrid creatures and whose elongated bodies are intertwined in winding ribbons and tightly packed over the body of the vessel (Fig. 7). In contrast to the strong fragmentation of the decorative zones in the bronzes from Chu, the bronzes from Jin are characterized by decorative zones or bands that extend around the entire body of the vessel and are self-contained. The abstract ribbon decorations are complemented by regularly inserted monoculi. Overall, however, the decors are worked in very flat, not very extensive relief. The very finely crafted decors were made during casting, as findings from casting molds with a decal negative already incorporated during excavations have shown.

What is special about the bronzes from Jin is that they partly take up old shang decors - they often make use of taotie and leiwen - but also that they take up naturalistic animals such as fish, turtles and ducks that are rather unusual for bronze art decors. Ornamental ridges and applications are very rare and are mostly represented by animals kept in a subtle and naturalistic way. Henkel and its approaches can easily take on dragon or taotie shape. Inlay work is very rare; gold is usually used.

With the disintegration of Jin into Han , Zhao and Wei , a change in the surface design of the bronzes began. The shapes usual for the Liyu style are retained and abstract, intertwined dragon patterns are still present, but these are partly shortened and simplified. Instead, the inlay technique flourishes, with gold, copper and the turquoise inlays not used since the Shang period, as well as malachite, being processed on a large scale.

The lines change. Instead of horizontal and vertical elements, there are diagonal lines that define diamond-shaped or triangular decorative zones. The inlaid gold or copper components either serve to emphasize individual decorative elements such as dragons or to separate individual decorative fields from one another and accentuate the lines. By the fourth century, gold and silver had almost completely supplanted other metals such as copper as inlay materials.

The periphery

In addition to the culture of the central lowlands around the Yellow River, there were other cultures that lay on the territory of today's China and were connected with the Shang and Zhou through trade relations, but still had their own culture. The area of today's Hunan Province should be considered separately, which was under the influence of the Shang and Zhou, but produced a distinctive regional style before the state of Chu was founded in the area.

Shu culture

A special case study for an autochthonous culture that was in certain contact with the culture of the Chinese heartland is the Shu culture, which was located in today's Sichuan province . Its heyday was around the second half of the Shang Dynasty and the early phase of the Zhou. They were found in Sanxingdui (about 40 kilometers northeast of the provincial capital Chengdu ) and Jinsha in the urban area of Chengdu. The two archaeological sites contained large amounts of artifacts, the metalwork of which caused a stir. In contrast to the Chinese heartland, the Shu craftsmen mastered casting in permanent molds, but they used a number of simple shapes per object that were put together.

In contrast to the Shang, the Shu made noticeably few vessels. In the two sacrificial pits at the Sanxingdui site, of the hundreds of bronze objects found, only about a dozen vessels are kept. These are formally very similar to the Zun and lei of the Shang, but are hardly direct imports, but either from local production or by a people who settled between the Shang and Shu and were negotiated according to Sanxingdui. Tripod vessels are unknown.

The numerous representations of human heads or masks, which are anthropomorphic and theriomorphic, are special. Figures were also found in the sacrificial pits. The smaller ones measure about 10 centimeters and impress with their expressive presentation. In addition, the second sacrificial pit contained the oldest life-size human figure representation made of bronze. The figure is called a “large standing figure” and is around 2.60 meters high including the base. Furthermore, bronze sacrificial tables or altars have come to light and also depictions of trees with widely ramified branches to which elements such as birds or flowers were attached. The largest reconstructed tree is about 3.96 meters high.

The dominant decorative elements are very different from those of the Shang and Zhou. An important technique that was used to prepare the bronze objects was gilding with gold leaf. Masks and heads were covered with fine gold leaves, which, in contrast to the pieces that were not gilded, produced a metallic sheen that set these pieces apart from the rest.

Furthermore, pigment residues were found on head and mask representations, mostly carbon black or vermilion, to mark eyebrows or pupils or to dye lips red. Such examples of surface treatment with high-contrast colors by means of gold plating or pigment application are not known from the Chinese heartland.

The Shu bronzes also differ in form and function. They are more sculptural and in themselves a decorative ornament or decor than the vessels of the Shang and Zhou, which are only decoration carriers. Although surface decors such as leiwen also appear in a comparable form, there are snake or line patterns that are much more similar to the plastic dragon depictions of the Shu bronzes than ordinary leiwen .

The Shu dragon depictions differ greatly from those of the Shang and Zhou. Your kites have elaborate nose or head combs, as well as back sails. They always have four legs that end in fist-shaped feet. Dragons are a relatively common motif and can be found, for example, as decoration of the mantle of the large standing figure in relief or in plastic elaboration on the bronze trees and the altars. Another common motif are eye spots or sunspots and sun wheels. These also appear in relief cast form on the clothing or headdress of figures, but also in plastic elaboration in the form of fittings or plaques. Birds are represented three-dimensionally, for example as an ornament on the branches of the bronze trees, but also as individual sculptures. A cast bird of prey head with a hooked bill and a rooster with an imposing head crest are particularly popular.

Other animals that were often depicted are elephants, which must have played a special role in the everyday or religious life of the Shu. Four elephant heads adorn the base of the large standing figure. The presence of floral elements is a characteristic of the Shu bronzes. These are completely absent from the Shang and Zhou, while the Shu made representations of entire trees and the associated elements such as leaves, buds and flowers that adorned these trees. The headdress of the standing figure and a smaller figure show either leaf or feather decoration.

In the course of the western Zhou period, the influence of the bronze art of the heartland on that of the Shu culture increased. Decorative elements such as kui dragons and the leiwen have a permanent place in the decorations of bronze vessels. Representations of people became rarer, but naturalism in animal representations increased. The frequency with which round decorative elements are used is striking. These are curled up dragons or snakes that have highly abstract bodies that could possibly be a reminiscence of the sun wheel motif found in Sanxingdui.

literature

- Bagley, Robert (Ed.): Ancient Sichuan: Treasures from a Lost Civilization Princeton University Press, Seattle 2000, ISBN 978-0-691-08851-8

- Butz, Herbert: Early Chinese bronzes from the Klingenberg collection, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-88609-225-9

- Chang, Willow Weilan Hai (Ed.): "Along the Yangzi River: Regional Culture of the Bronze Age from Hunan" China Institute: New York 2011, ISBN 978-0-9774054-6-6

- Chen Zhi: A Study of the Bird Cult of the Shang People, in: Monumenta Serica, Vol. 47 (1999), pp. 127-147

- Falkenhausen, Lothar von: Suspended Music: Chime-Bells in the Culture of Bronze Age China University of California Press, Berkeley u. a. 1993, ISBN 978-0-520-07378-4

- Goepper, Roger (ed.): The old China. People and gods in the Middle Kingdom 5000 BC Chr. - 22 AD Hirmer, Munich 1995, ISBN 978-3-7774-6640-8

- Rawson, Jessica: "Chinese Bronzes: Art and Ritual" British Museum: London 1987

- 四川省 博物館 & 彭 縣 文物 舘 (編) (Sichuan Provincial Museum & Peng County Culture Hall (ed.)): 四川 彭 縣 西周 窖藏 銅器 (Bronze objects from the western Zhou period stored in Peng County (Sichuan)), in : 考古 (Kaogu) (1981: 6), pp. 496-499

- So, Jenny: "Eastern Zhou Bronzes from the Arthur M Sackler Collections Volume III" Arthur M. Sackler Foundation: New York 1995

- 肖 先進 , 劉家勝 等 (Xiao Xianjin, Liu Jiasheng et al.): 三星堆 發現 發掘 始末 (The discoveries and excavations in Sanxingdui from beginning to end)四川 人民出版社, 成都 2001, ISBN 7-220-05435-1

- Yu Weichao; Kleeman, Terry (transl.): The Origins of the Cultures of the Eastern Zhou, in: Early China 9/10 (1983-1985), pp. 307-314

Remarks

- ↑ This example does not come from the Chinese heartland, but takes up a motif that is familiar to the Shang and implements it.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b YU & KLEEMAN 1984: 309

- ↑ http://ctext.org/lv-shi-chun-qiu/xian-shi

- ↑ CHANG 2011: 28f

- ↑ CHENG 1999: 129

- ↑ http://ctext.org/lv-shi-chun-qiu/ying-tong

- ↑ BUTZ: 1993: 14 (Fig. 3)

- ↑ FALKENHAUSEN 1993: 73

- ↑ CHANG 2011: 40

- ↑ RAWSON 1987 52

- ↑ RAWSON 1987: 52f

- ↑ SO 1995: 24.33f

- ↑ SO 1995: 34

- ↑ CHANG 2011: 98.103

- ↑ FALKENHAUSEN 1993: 72 (Fig. 31)

- ↑ a b SO 1995: 37

- ↑ SO 1995: 37,130.141

- ^ SO 1995: 40

- ^ SO 1995: 47

- ↑ SO 1995: 48f

- ↑ RAWSON 1987 55

- ↑ CHANG 2011: 19-22

- ↑ XIAO 2001: 82

- ↑ XIAO 2001: 5

- ↑ XIAO 2001: 62

- ↑ XIAO 2001: 78-80

- ↑ 四川省 博物館 & 彭 縣 文物 舘, 1981: 496-498