Free Church

Free church originally referred to a Protestant church that - in contrast to a state church - was independent of the state . As a result of the separation of religion and state , which has now largely been achieved in Europe , the meaning of the word can no longer be clearly defined. The term free church is used today to delimit a certain church from popular churches . The attribute “free” is understood differently, for example in the sense of voluntary membership, organizational independence or as an indication of a certain theological attitude.

Traditional categories of free churches

Among the free churches in the original sense, a distinction is made between the following categories (although not all free churches can be clearly classified in this scheme):

- the "principle" free churches. This means those free churches for which the separation of church and state as well as voluntary membership are among the principles of their ecclesiology . The Baptists and Mennonites , for example, belong to this species .

- Free churches that have emerged from internal church renewal movements ( Pietism , community movement , methodism ). This subheading includes the Moravian Brethren and the Salvation Army . Other groups, e.g. B. the Evangelical Society for Germany or the city mission , are organized like a free church, but officially a free work within the EKD and thus strictly speaking not a free church.

- Churches that have separated from an existing church due to a “confessional emergency” and have organized themselves as a free church. One speaks of a confessional emergency when the leadership of a church from the point of view of some of its members deviates from essential beliefs, e.g. B. enters into too close a relationship with the state. The Evangelical Brethren Congregation Korntal belongs to this group .

Most of the old confessional churches , which include the Old Catholic Church , the Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church (SELK) and related old confessional Lutheran churches, are not free churches according to their self-image, since for them “in contrast to the classical free churches, their existence is a new one owe (theological and / or spiritual) reform approach, ... it is precisely the adherence to the traditional that [is] characteristic, even if in the course of their history they have proven to be capable of change. ”The Evangelical Old Reformed Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Free Church (ELFK ) , on the other hand, also call themselves a free church.

Free church term

The increasing separation of church and state implements a concern of the free churches. This gives all churches a status that corresponds to that of “free churches”. This makes it more difficult to clearly define what the traditional free churches have in common. By returning to the essence of the “free church”, an attempt is made to clearly distinguish it from other forms of church.

A number of Christian churches and congregations have the word free church in their name. Examples are the Free Church of Scotland , the Eglise évangélique libre du Canton de Vaud , the Free Church Uster , the Chiesa Libere at the Italian Waldensian Free Churches, the Federation of Evangelical Free Churches , the Federation of Free Church Pentecostal Congregations , the Free Church Federation of the Congregation God's , the free churches in Austria as well as in the Lutheran environment the Fríkirkja and the Hanoverian Evangelical Lutheran Free Church .

Free Church as the result of a certain basic theological attitude

Free churches want to implement the Reformation alone Christ radically: They deny that salvation lies in belonging to a certain external church organization. They therefore reject the compulsion to belong to the respective “state church” and also the claim of exclusive sects that salvation can only be found with them.

In the German-speaking area, many free churches can be classified as evangelical in theological terms ; however, there is a broad spectrum, from fundamentalist to liberal .

Free church as a voluntary church

Voluntary churches differentiate themselves from people's churches in that they expect their members of religious age to make a conscious decision to join the respective church. This can be understood as a consequence of the principle “Christ alone”.

Infant baptism is common in popular churches; however, those voluntary churches that also practice infant baptism do not consider this to be sufficient for full membership (e.g. in the Evangelical Methodist Church ).

Voluntariness is no longer such a clear distinguishing feature, since membership in popular churches can also be based on voluntariness. It is possible to leave the church (although in the self- image of the Catholic Church, for example, members who have left also remain due to the indelible characteristic conveyed by baptism ). Insofar as membership in a people's church is not based on one's own voluntary decision, the aspect of voluntariness remains a possible distinguishing feature of “free churches” (see above on the traditional “free churches in principle”). Anyone who never makes an active decision of their own with regard to church membership naturally also does not become a member of a free church; but he can very well - if he was baptized as an infant - remain a member of his people's church, as many inactive members of people's churches "do". There remains a practical difference between free and popular churches, despite the possibility of leaving.

Free church as a minority church

As typical for free churches, their smaller number of members compared to national churches is sometimes seen. Accordingly, a free church is a numerically small alternative to one or more national churches . Such an approach only fits in countries with such people's churches that cover the majority or at least a large part of the population, but not in a strongly mixed denominational landscape, e.g. B. the United States of America .

The informative value of a measured variable based on the formal number of members is limited by the fact that only a fraction of the members of Volkskirchen participate actively in community life (in the regional churches of the Evangelical Church in Germany, around 3–5% of members attend Sunday services). In contrast, in free churches the number of active members and friends is generally similar to the formal number of members. When looking at the people actually active in the individual churches, the difference in size is then significantly smaller.

In a minority situation there are not only free churches, but also special communities (formerly often called “sects”). This also shows that the finding of a comparatively small size only superficially captures the essence of a free church.

historical overview

The church concept of the Reformation and the free church alternative

The Reformation took their State - and concept of the Church as a legacy of the post-Constantinian late antiquity and the Middle Ages ; therefore she only knew one type of church - the state church . This was based on the uniformity of the worldview , which only knew an absolute religious truth that encompassed the life of the rulers and all subjects and unified them. It was logical for this understanding that state and church should join forces in order to educate all citizens in this absolute truth - even if in practice there were often conflicts between state and church. But fundamentally different religious convictions, which would have led to the separation from the state church, could not be tolerated by either the state or the church. It is true that the Reformation softened this basic consensus to a certain extent by establishing a different church fellowship alongside the Roman Catholic Church, which sees itself as universal . In this church - according to the reformers' view - religious truth was freed from human-historical additions and therefore appeared purer and more original than in the traditional one. Nevertheless, the principle that only one church can exist in a state remained for the Reformation and ultimately led to the well-known compromise cuius regio, eius religio (whose country [is] the religion) of the Augsburg Religious Peace of 1555 between Old Believers and Lutherans , which was then enshrined in the Peace of Westphalia (1648) for the following centuries (now including the Reformed ). The state church system was even strengthened by the Reformation and its heirs, in that the old, closely intertwined coexistence of secular and spiritual authorities was replaced by the subordination of the church to the state. The principle of the state church was not gradually broken in Europe until the middle of the 19th century - due to the change in the concept of the state and the democratization of society.

The free churches, which were not guaranteed the right to exist as a result of the Westphalian peace, did not orientate themselves on this state church model, but on what they saw as the New Testament congregation form. They understood the community as a community of believers who “wanted to obey God more than men” and were only willing to give “the emperor” what the Bible was entitled to give him . Again and again, these views brought the free church movements into strong opposition to the state and its church. Many members of the Free Churches - think of the Anabaptists , for example - paid for their beliefs with persecution and martyrdom . America and Russia became a new home for many free churches of the 17th and 18th centuries in which to live according to their beliefs. While they were granted very limited religious freedom in Tsarist and Orthodox Russia , they experienced America (especially the USA ) as the “land of unlimited possibilities”. Here they played a key role in building up the young states. Around 1643, for example, the Baptist Roger Williams drafted a constitution for Rhode Island in which, for the first time in history, the complete separation of church and state was enshrined. This Constitution later became the basis of the United States Constitution .

Historical developments

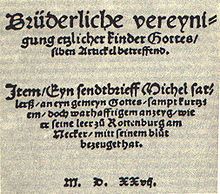

The Waldensians emerged from a lay movement in France and northern Italy in the 12th century . The historical roots of the Mennonites lie in the partially radical Anabaptist movement of the 16th century, which triggered violent reactions and persecution by breaking out of the established churches. The Mennonites occupy a special position among the free churches which - albeit in small numbers - have asserted themselves in continental Europe for centuries.

In England and Scotland in the 17th century there were emphatically Calvinist - Reformed splits from the Anglican Church such as the Puritans , from which the Presbyterians , Congregationalists and Baptists developed. Such divisions did not always remain free churches everywhere. Thus, the Presbyterian Church in Scotland became the State Church (making the Scottish Anglicans a Free Church) and the Puritans established colonies in Massachusetts in which they assumed the role of the State Church. Even in the time of the Commonwealth under Oliver Cromwell , the Puritans enjoyed the protection of the English state. 1843 split into the so-called "disruption" the Free Church of Scotland , due to the rejection of the church patronage also Reformed Calvinist from the, by the state privileged Church of Scotland from. In England the Quakers were formed under George Fox .

In the German-speaking area , in addition to the Mennonites already mentioned, free-church congregations emerged primarily from Pietism , such as the Moravian Brethren under Nikolaus Graf von Zinzendorf .

In the 18th century, the Methodist movement emerged in England mainly through Charles and John Wesley as a far-reaching reform, revival and sanctification movement, initially within the Anglican Church . The Methodist Episcopal Church was founded in the USA at the end of 1784 . In the period that followed, Methodist churches were founded in the United States and England. In the mid to late 19th century returnees from the United States and missionaries from England founded Methodist congregations in German-speaking countries. Today there are three international Methodist churches in German-speaking countries: the United Methodist Church , the Church of the Nazarene and the Wesleyan Church . They are all part of the World Council of Methodist Churches , founded in 1881.

To a certain extent, as a late consequence of the revolutionary Anglo-Saxon free-church movement at the beginning of the 19th century and the associated fragmentation into several congregational groups, the first so-called Brethren congregations emerged first in the United Kingdom and later also in Germany ( also Darbysten after one of their founders, John Nelson Darby called).

One of the pioneers of the newer Baptist free church movement that developed in the 19th century was Johann Gerhard Oncken , who founded the first German Baptist congregation in Hamburg in 1834 , which subsequently became the nucleus of most European Baptist churches.

In Elberfeld (today a district of Wuppertal ), under Hermann Heinrich Grafe, the first Free Evangelical Congregation was founded in 1854 in protest against the liberal communion practice of the Protestant regional churches , which adopted the Baptist concept of baptism , but did not demand it from believers who were already baptized as children to be baptized.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the so-called sanctification movement (its roots are in Methodism ) became the Pentecostal movement , the church family of Christianity, which is currently experiencing the highest growth. In the time of National Socialism , the destroyed churches of the Confessing Church also formed a kind of free church.

In the second half of the 20th century, so-called nondenominational or independent free churches came into being. Some inner-church renewal movements also developed into independent free churches in the 20th century (see, for example, Evangelical Society for Germany ).

Free churches in the German-speaking area

Many free churches in German-speaking countries can look back on a longer history. They have developed organizational structures according to their respective ecclesiology and work together on various levels, for example in the Working Group of Christian Churches in Germany and Switzerland , in the German , Austrian and Swiss Evangelical Alliance , in the Union of Evangelical Free Churches , the Association of Evangelicals Free churches and congregations in Switzerland or the free churches in Austria .

List of traditional free churches in German-speaking countries

- Working Group of Mennonite Congregations (AMG)

- MovementPlus Switzerland (BPlus)

- Brethren congregations ("Christian Assembly", "Free Brotherhood ")

- Federation of Baptist Congregations in Austria (BBGÖ)

- Federation of Evangelical Congregations in Austria (BEG)

- Federation of Evangelical Free Churches (BEFG), consisting of Baptist , Brethren and Elim congregations

- Federation of Free Protestant Congregations in Germany (FeG)

- Federation of Free Church Pentecostal Congregations (BFP)

- German Annual Assembly ( Quakers )

- Elaia Christian Congregations (ECG)

- Methodist Church (UMC)

- Evangelical Reformed Church Westminster Confession (ERKWB, in Austria and Switzerland)

- Evangelical Brethren Congregation Korntal ; Evangelical Brethren Congregation Wilhelmsdorf

- Evangelical Free Church GvC in Switzerland (GvC)

- Evangelical Free Churches in Switzerland (EFG)

- Methodist Church in Austria (UMC)

- Free Christian Community - Pentecostal Church in Austria (FCGÖ)

- Free Evangelical Congregations in Switzerland (FEG)

- Seventh-day Adventist Church (SDA)

- Free Church Federation of God's Congregation (FBGG)

- Church for Christ (until 2009: Evangelical Brotherhood)

- Church of God Germany KdöR (Pentecostal)

- Salvation Army

- Moravian Brethren Community (Evangelical Brothers Unity, EBU)

- Church of the Nazarene

- Conference of the Mennonites of Switzerland

- Mennonite Free Church Austria (MFÖ)

- Mülheim Association of Free Church Evangelical Congregations

- Pentecostal Church of God in Austria

- Chrischona International (in Germany it belongs to the Evangelical Church as a "free work", but in Switzerland to the Association of Evangelical Free Churches and Congregations )

- Swiss Pentecost Mission

- Association of Apostolic Congregations

- Association of Free Missionary Churches

New free church church planting

Since the 1970s, so-called independent congregations have developed - especially in the big cities - which have free-church structures but do not belong to the classic free churches. In 2003, the Baptist theologian Heinrich Christian Rust declared that there are now more Christians in these free congregations than in the classic free churches that are united to form the Association of Evangelical Free Churches (VEF). Rust assumes over 300,000 members in these free churches. In particular, influences from the American Pentecostal movement (partly through targeted church planting assignments ) contributed to this development. They are mostly without any kind of connection, but mostly belong to some network (e.g. D-Netz). In recent times, more and more independent and small communities have emerged from house groups or through divisions.

Another phenomenon is the founding of communities and communities of different types among repatriates .

The following types can be identified in these so-called transdenominational communities:

- Churches with a Pentecostal charismatic character

- Churches with an evangelical missionary character

- Churches with an evangelical- conservative character

- Churches with a neo-Calvinist character

- House Church Movement

- Youth trend movements

- Free-church congregations that emerged from the work of non-denominational mission organizations (e.g. youth with a mission ).

Associations and associations

- Association of Evangelical Free Churches (VEF), Germany

- Free Churches in Austria (FKÖ)

- Association of Protestant Free Churches and Congregations in Switzerland (VFG)

Rejection of church tax and funding

One point of criticism of some Free Churches of the Protestant and Catholic Churches in Germany is their financing through the church tax, which is collected by state authorities against reimbursement of expenses (as in Germany and mainly in Switzerland ; in Austria the churches collect the church contribution themselves). Free church communities advocate a separation of church and state. Accordingly, they reject the collection of church taxes by state organs and finance themselves from voluntary contributions from their members and friends. In general there is no formal obligation to pay taxes, so that on the basis of the self-assessment there are both “zero payers” and members who make substantial contributions. In some cases the so-called “Biblical tithe ” (10% of income - which is usually not defined in more detail) is used as a benchmark. However, there are a few free churches that levy church taxes.

Ecumenical cooperation between free churches

The ecumenical movements have often been initiated by free church engagement and have been decisively shaped in their developments. Free churches are convinced that the church of Jesus is bigger than their own denomination. That is why they are usually open to interdenominational dialogue and often consciously seek encounters and cooperation with other Christians. The Association of Evangelical Free Churches (VEF) in Germany and the Association of Evangelical Free Churches and Congregations in Switzerland are particular examples of this. In Austria, five Protestant Free Churches have joined together to form the umbrella organization Free Churches in Austria and have thus been able to obtain state recognition as a church community. Many (also non-evangelical) free churches are also involved in the working group of Christian churches in Germany and Switzerland . The Evangelical Alliance is a special forum in which Evangelical Free Church Christians get involved together with those from the Evangelical regional churches . In addition, various free churches (e.g. Baptists, Methodists and Pentecostals) hold convergence talks with other denominations about theological differences. As a signatory of the Leuenberg Agreement, the Evangelical Methodist Church established full church fellowship with the member churches of the EKD and the other participating churches.

Historiography by and about free churches

The individual church

Historiography concerning free churches is based on the free churches themselves: One member writes for other members. At the beginning there is often an awareness of success: the free church in question can already look back on considerable growth. The smallest object of such historiography is the individual local church. The occasion for looking back at one's own history is often an anniversary. Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer describes nine areas of tension when writing a community history and puts them into question form:

- Describe objectively or evaluate subjectively? Representing history or preaching with historical material? Use pastor service times as the highest structuring principle? Strive for completeness or select evaluative? Present problems openly or conciliatory cover up? Looking back from the perspective of the present church (leadership)? Present chronologically or cover thematically? Trust the sources or criticize them? Understand the past or use the present as a yardstick?

These questions point to areas of tension in which the historian stands and in which he has to decide to what extent to follow which tendency.

As a community federation

The next level is reached through (mostly: self-) reflection on the history of a free church or a parish union. The Association for Free Church Research is particularly dedicated to history. The symposia and workshops each have a specific theme; in 2011 e.g. B. The individual free churches in the Weimar Republic and in the Nazi era were considered. The presentations will be published in the following yearbook (the topics mentioned in 2012). This results in the possibility of comparing the Free Churches in the context of current events. In his sketch of a free evangelical history , Andreas Heiser describes different understandings of history that he encountered in the historical literature of the free evangelical communities : In the history of the church, primarily progress or primarily decadence can be seen. A comparison of world and salvation history can be in the foreground, and there is a personal history as well as a mentality history approach. The sources and methodological issues of Austrian history to free churches studied Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer. He pays particular attention to the upheavals in the history of the free churches; In the history of the Austrian Baptists he believes he can perceive several shifts and upheavals, such as internationalization (around 1960), interdenominationalization (after 1970) and an equalization surge (around 1980). A comparative history of the free churches would be necessary in order to recognize the extent to which such changes took place across the free churches at roughly the same time.

Within the framework of Christianity

At the next level, the history of individual or all free churches is integrated into a broad-based church history. In such, however, free churches are often ignored, especially in Austria, where the free churches have a small number of members. Gustav Reingrabner , for example, devotes a separate chapter of his history of Protestants in Austria (1981) to the Anabaptists of the early 16th century , but does not mention any newer free churches such as Baptists or Methodists. So here “Protestantism” is largely restricted to the Evangelical Church. But even in the extensive overall presentation of a history of Christianity in Austria (2003), newer free churches are only listed once by name, without any description.

See also

- Association for Free Church Research

- List of German-speaking free church historians

- Working group architecture and free church

- Free churches in individual regions: Free churches in East Friesland , Free churches in Austria

literature

- Bibliography on the history of the free churches , annually (since 1992) in: Free Church Research , ed. from the Association for Free Church Research, z. B. Nr. 20, 2011, ISBN 978-3-934109-12-4 (each year contains the bibliography for the previous year).

- Erich Geldbach : Free Churches - Heritage, Shape and Effect (= Bensheimer Hefte, Volume 70). 2nd Edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-525-87157-0 .

- Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer : Free Church between the Volkskirche and the sect. Attempted a definition based on three characteristics. Terms and criteria. In: Free Church Research 17 (2008), pp. 290–296 (three characteristics: Christ alone , individuality, distance from the state).

- Wolfgang E. Heinrichs : Free churches - a modern church form. Formation and development of five free churches in Wuppertal . Brunnen Verlag, Giessen 1989 (2nd edition 1990).

- Reinhard Hempelmann : The "new" Protestant free churches . In: Material service of the Evangelical Central Office for Weltanschauungsfragen, 2002, Issue 6, pp. 161–167, ISSN 0721-2402 ( short version ).

- Hans Krech, Matthias Kleiminger (Ed.): Handbook religious communities and world views. Free churches, Pentecostal charismatic movements and other independent communities, Christian sects, new revelers, new revelation movements and new religions, esoteric and neo-nostic world views and movements, religious groups and currents from Asia, providers of life support and psycho-organizations . Published on behalf of the church leadership of the VELKD . 6th, revised and expanded edition. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2006, ISBN 978-3-579-03585-7 .

- Hans-Martin Niethammer: Church membership in the free church. Church-sociological study based on an empirical survey among Methodists. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1995, ISBN 3-525-56541-0 (= Church and Denomination, Vol. 37; Dissertation).

- Hans Schwarz : Free Church . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Vol. 11, 1983, pp. 550-563.

- Association of Evangelical Free Churches (ed.): Free Church Handbook. Information - addresses - reports. Wuppertal 2000, ISBN 3-417-24154-5 (“Texts and Documents” not yet overtaken by the 2004 edition).

- Association of Evangelical Free Churches (ed.): Free Church Handbook. Information. Addresses. Texts. Reports. Wuppertal 2004, ISBN 3-417-24868-X .

- Karl Heinz Voigt: Free churches in Germany (19th and 20th centuries). Evangelische Verlags-Anstalt, Leipzig 2004, ISBN 3-374-02230-8 (Series Church History in Individual Representations III / 6).

- Gunnar Westin: History of Free Churches. The way of the free Christian communities through the centuries . Oncken-Verlag: Kassel 1958.

- Friedrich Schneider: Free Churches and Media. In: Michael Klöcker, Udo Tworuschka (Hg.): Handbuch der Religionen. Churches and other religious communities in Germany and in German-speaking countries . Olzog, Landsberg am Lech, 58th supplementary delivery (2018), XIV - 3.1.2.2.

Web links

- Free churches in Austria

- Erich Geldbach : Free Churches (Mennonite Lexicon) ; accessed on May 26, 2014

- Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer : Timeline of the History of Austria's Free Churches , in: MBS Texte 196, 2020.

- Association of Protestant Free Churches and Congregations in Switzerland

- Association for Free Church Research

- Association of Evangelical Free Churches in Germany

Individual evidence

- ^ Georg Hintzen: Old denominational churches. In: Kleine Konfessionskunde, ed. from the Johann Adam Möhler Institute, Paderborn 1996, p. 307 ff.

- ^ Official website of the Old Reformed Church

- ^ Graf-Stuhlhofer: Free Church between the People's Church and the Sect.

- ^ Evangelical Church in Germany: Statistics of the EKD. Retrieved January 11, 2018 .

- ↑ Friends is not a judgmental expression here, but a common term in free church circles for people who attend church services and events and who work, donate, etc., but are not members. See as an example: In addition to the members, a strong growth in the circle of friends ... led to an increased space requirement ( http://www.efg-buchholz.de/christuskirche-historie.php ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: Der Link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this note. , Read on May 2, 2012).

- ↑ List of Calvinist communities, ( Memento from January 28, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) accessed on: January 28, 2016.

- ↑ Reinhard Hempelmann: The "new" Protestant free churches .

- ↑ The ecumenical service notice is at the entrance to the town from the north (East Frisia) . The green church is here for the local Baptist church , the Free Evangelical community , the Pentecostal Church and as well as the Mennonite Church . The blue church refers to the Seventh-day Adventist Church

- ↑ Eight areas of tension in Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer (Ed.): Fresh water on arid land. Festschrift for the 50th anniversary of the Federation of Baptist Congregations in Austria (= Baptism Studies ; Vol. 7). Oncken, Kassel 2005, pp. 34-37. A ninth area of tension in Graf-Stuhlhofer: Freikirchen in Österreich, 2008/09, pp. 278–282.

- ↑ Andreas Heiser: How to write history. Historical sketch of a free evangelical history . In: Theological Conversation. Free Church Contributions to Theology 16, 2012, pp. 129–147.

- ^ Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer: Free Churches in Austria since 1846. On the sources and on questions of method. In: Yearbook for the History of Protestantism in Austria 124/125 (2008/09), pp. 270–302.

- ^ Rudolf Leeb, Maximilian Liebmann , Georg Scheibelreiter, Peter G. Tropper: History of Christianity in Austria. From late antiquity to the present (series Austrian history , edited by Herwig Wolfram ). Ueberreuter, 2003, p. 450.