Friedrich Accum

Friedrich Christian Accum (born March 29, 1769 in Bückeburg , † June 28, 1838 in Berlin ) was a German chemist whose main merits were promoting the production of luminous gas , the fight against food adulteration and the popularization of chemistry.

Between 1793 and 1821 Accum lived in London , where he ran his own laboratory, sold chemicals and laboratory equipment , gave classes in practical chemistry, and worked at several scientific research institutes. Inspired by Friedrich Albert Winsor (1763–1830) and his long-term advertising campaign for gas lighting , Accum began to deal with the subject of luminous gas production. On behalf of the Gaslight and Coke Company , founded in 1810 , he carried out numerous experiments and was appointed to its first board in 1812. With the establishment of the first London gas station, led by Accum, the use of gas lighting was expanded from industrial to public and private areas.

Accum's Treatise on Adulteration of Food , published in 1820 , in which he denounced the use of toxic food additives , marks the beginning of a conscious approach to food. Accum was the first to take on this topic and at the same time achieved a broad public impact. While his books were selling well with the public, his educational work among London food producers earned him numerous enemies. After a lawsuit against him, Accum left England and spent the rest of his life teaching at the industrial institute and at the building academy in Berlin.

His writings, which are mainly published in English, are characterized by a particular degree of general intelligibility. In this way Accum contributed significantly to the popularization of chemistry.

life and work

Youth and apprenticeship years

Friedrich Accum was born on March 29, 1769 in Bückeburg , about 50 km west of Hanover . His father came from Vlotho on the Weser and had initially served in an infantry regiment of Count Wilhelm von Schaumburg-Lippe . In 1755 Accum's father converted from Judaism to the Evangelical Reformed faith and shortly afterwards married Judith Berth dit La Motte in Bückeburg, the daughter of a hat manufacturer from the French colony of Berlin and granddaughter of a Huguenot religious refugee. At his baptism he changed his maiden name Markus Herz to Christian Accum. Both the first name Christian , which literally means “follower of Christ”, and the surname, derived from the Hebrew word “Akum” for “non-Jew”, emphasized the change of religion in a particularly emphatic way. It is unknown whether this was done at the urging of his bride's family or of her own volition. In any case, after the wedding, Christian Accum began self-employed as a merchant and soap manufacturer in a house that originally belonged to his wife's parents at Bückeburger Schulstrasse 141 and acquired citizenship of the city nine years after his wedding. Just three years after Friedrich's baptism on April 2, 1769, Christian Accum died at the age of forty-five, leaving behind Friedrich and his mother the older siblings Philipp Ernst, Henriette Charlotte and the eight-month-old Ernestine, who died at the age of five.

Friedrich Accum attended the Adolfinum grammar school in Bückeburg and also received private lessons in French and English. After finishing school, he completed an apprenticeship in the pharmacy of the Brande family, friends of the Accums, in Hanover. The Brandes also operated a branch in London and were the pharmacists of the Anglo-Hanoverian King George III . Since London, as the center of technology, attracted young people from all over Europe interested in science at the end of the 18th century, Friedrich Accum also went there in 1793 and worked as an assistant in the Brande pharmacy on Arlington Street.

The first years in London

In addition to his work in the Brandes Pharmacy, Accum initially studied science and attended medical lectures at the School of Anatomy on Great Windmill Street. He was in contact with the surgeon Anthony Carlisle (1768-1840) and the London chemist William Nicholson (1753-1815), in whose journal Nicholson's Journal he published his first paper in 1798 - at the age of twenty-nine.

On May 10, 1798 Accum, who had meanwhile anglicized his name to "Frederick Accum", married the Englishwoman Mary Ann Simpson (born March 6, 1777, † March 1, 1816 in London). He had a total of eight children with her, six of whom were either born dead or died in childhood. His eldest child, their daughter Flora Eliza (born May 17, 1799), married Ernst Müller, with whom they had three children. His son Friedrich Ernst Accum (born April 3, 1801; † January 28, 1869) had four children with his wife Charlotte Wilhelmina Johanna Henkel, whose descendants who were still alive in 2006 no longer bore the name Accum.

In the fall of 1799, a translation of Franz Carl Achard's pioneering work on sugar extraction from beetroot appeared in Nicholson's Journal . Until then, sugar cane grown overseas was the only crop from which sugar was made. Accordingly, the possibility of local sugar production was received with great interest. Shortly after the publication, Accum had samples of the beet sugar sent to London from Berlin and presented them to William Nicholson. It was the first time beet sugar had come to England, and Nicholson published a detailed report in his journal in January 1800 of the research he had carried out and found no loss of taste to the cane sugar.

Laboratory operator, businessman and private teacher

In 1800, Accum and his family moved from 17 Haymarket to 11 Old Compton Street, where he lived for the next twenty years and used his house for teaching students as well as for experimenting and selling chemicals and equipment. On his professional cards from that period , with which Accum offered its services, he himself described his activity in Old Compton Street as follows:

“Mr Accum acquaints the Patrons and Amateurs of Chemistry that he continues to give private Courses of Lectures on Operative and Philosophical Chemistry, Practical Pharmacy and the Art of Analysis, as well as to take Resident Pupils in his House, and that he keeps constantly on sale in as pure a state as possible, all the Re-Agents and Articles of Research made use of in Experimental Chemistry, together with a complete Collection of Chemical Apparatus and Instruments calculated to suit the conveniences of Different Purchasers. "

“Mr. Accum indicates to his customers and those who love chemistry that he is continuing his private series of lectures on applied and theoretical chemistry, practical pharmacy and the art of analysis, as well as taking students into his home, and that he will always have all reagents and articles for chemical experiments keeps in stock for sale in the purest possible condition, together with a complete collection of chemical apparatus and instruments tailored to the needs of different buyers. "

Accum distributed catalogs of its goods to its customers in London in Old Compton Street and, on request, also sent them to other cities in England and abroad.

Accum's Laboratory on Old Compton Street was for many years the only major facility in Great Britain that offered practical laboratory exercises in addition to theoretical chemistry lectures. Accum's classes attracted a sometimes prominent audience. His audience included such well-known London politicians as the future Prime Minister Lord Palmerston , the 5th Duke of Bedford and the Duke of Northumberland . At the same time, Accum's Laboratory was the first European chemistry school to be attended by students and scientists from the United States , among them such famous names as Benjamin Silliman and William Dandridge Peck . When Silliman later became Professor of Chemistry at Yale College (now Yale University ) in New Haven, he ordered the first laboratory equipment from Accum in London. Accum's biographer Charles Albert Browne suspected in a life sketch published in 1925 that evidence of deliveries from Accum's London store could still be found at some of the older American colleges .

When developing new laboratory equipment, Accum focused on practicality and low acquisition costs. Even laypeople should be enabled to carry out simple chemical tests. Accum developed portable laboratory boxes for the analysis of soil and rock samples for farmers, where no reagents could leak out even if they were overturned. The chests, priced between three and eighty pounds sterling , were the first portable chemistry labs.

Lecturer and Researcher

In March 1801, Friedrich Accum was appointed to the Royal Institution on Albemarle Street, a research institute founded only two years earlier by the experimental physicist Count Rumford . There he worked as a laboratory assistant under Humphry Davy , who at the same time had been appointed director of the laboratory and later was to become president of the Royal Society . Accum's work at the Royal Institution did not last long, however, as he left at his own request in September 1803. His biographer RJ Cole suspects a connection with the roughly simultaneous departure of Count Rumford to Paris, where he married Marie Lavoisier , the widow of the chemist Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier , who was guillotined in 1794 . Rumford had been the driving force behind Accum's appointment to the Royal Institution , and against this background it seems plausible that Accum's departure was linked to that of his sponsor.

By 1803, Accum published a number of other articles in Nicholson's Journal that covered a wide range of topics: from the appearance of benzoic acid in old vanilla pods to ways of determining the purity of drugs to observations on the explosiveness of sulfur - phosphorus mixtures. Far more important than these mostly short treatises, however, was his System of Theoretical and Practical Chemistry , published in 1803 . It was the first book published in English to draw on the groundbreaking findings of the French chemist Lavoisier, often referred to as the “father of modern chemistry” . In addition, it was characterized by the fact that the text was written in a language that was easy to understand. Cole therefore rates Accum's first extensive work as an "outstanding" achievement.

Accum gave his first chemistry and mineralogy lectures in a small room in his house on Old Compton Street. His audience grew so quickly, however, that he soon had to move to the Medical Theater on Cork Street. The great interest of the London public in his lectures led after Accum's departure from the Royal Institution to his employment at the Surrey Institution on London's Blackfriars Road. A newspaper advertisement in the London Times of January 6, 1809 shows that Accum offered courses in mineralogy and chemical analysis of metals every Wednesday evening at 7:00 p.m. His increased preoccupation with mineralogy at that time can also be seen in the titles of two books that Accum wrote between 1803 and 1809: In 1804 a two-volume work was published with the title A Practical Essay on the Analysis of Minerals (which was published in 1808 as A Manual of Analytical Mineralogy experienced a second edition) and in 1809 his Analysis of a Course of Lectures on Mineralogy . In addition, while working at the Surrey Institution , Accum published scientific articles on the chemical properties and ingredients of mineral water , which appeared in Alexander Tilloch's Philosophical Magazine from 1808 .

When the Parisian saltpetre boiler Bernard Courtois first extracted iodine from the ashes of seaweed in 1811 , his discovery was received with great interest by experts. In England, Accum was one of the first chemists to attempt to isolate the substance. In two articles that Accum published in Tilloch's Philosophical Journal in January and February 1814, he first pointed out the different iodine content of different types of seaweed and described in detail the steps that were necessary to obtain iodine.

Accum's role in the history of coal gas production

Industrial progress in the late 18th and early 19th centuries was largely dependent on the development of artificial lighting. Lighting a textile factory in the traditional way with thousands of candles or oil lamps would have cost enormous amounts of money and was forbidden for economic reasons alone. The new factory halls built with the advent of industrial production were not only spatially larger, they also had to be lit longer and brighter. Driven by the increased need for light and theoretically founded by Lavoisier's discovery that not only the carbon contained in the fuel but also the oxygen contained in the air is necessary for combustion, lighting technology, which has remained virtually unchanged for thousands of years, began to move at the end of the 18th century (Schivelbusch).

The properties of the gas resulting from the distillation of coal have been known since the publication of a letter from John Clayton to Robert Boyle in an edition of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in London in 1739. Clayton wrote:

“I took some pieces of coal and distilled them in a retort over an open fire. This initially produced a slimy liquid, soon after a black oil, and finally a gas that could not be condensed. However, it blew off the sealing ring and at times even caused the container to shatter. Once, when it had blown off the sealing ring of the retort and I approached to repair it, I observed that the escaping gas ignited and burned mightily on the flame of the candle. I extinguished it several times and lit it again. "

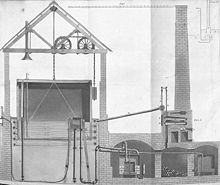

Until the end of the 18th century, however, this knowledge was hardly used in practice. The gas produced by the coking of hard coal escaped unused, and it was only the work of the Scotsman William Murdoch that marked the beginning of the use of coal gas for lighting purposes . First attempts by Georg Dixon in Cockfield in 1780, Johannes Petrus Minckeleers in 1783 in Löwen or Archibald Cochrane in 1787 in Culross Abbey were limited to individual rooms. The first prototypes of later gas works were made in a forge in Soho in 1802 and in a cotton mill in Salford near Manchester in 1805 . However, there was great skepticism towards the new technology. In 1810, Murdoch was asked by a member of the British House of Commons : "So you are really trying to convince us that there should be a lamp that can do without a wick?" It took the entire first decade of the 19th century to illuminate Factories developed luminous gas technology was also expanded to the sector of public and private life. Friedrich Accum played a key role here.

Encouraged by the businessman Friedrich Albert Winsor (1763-1830) - who emigrated to England himself - and his long-term advertising campaign for gas lighting, Accum began to deal with the subject of luminous gas production. Before the public company for light gas production advertised by Winsor since 1807 received the approval of the English parliament as "Chartered Gaslight and Coke Company" in 1810, Accum had testified before the parliamentary committee responsible for the approval as an expert. When the company finally commenced operations in 1812 after meeting the stipulated conditions, Friedrich Accum was appointed to its first board of directors. The construction of a gas station on Curtain Road, led by Accum, also marked the beginning of the history of the public gas supply. From now on, lighting with coal gas was no longer limited to the industrial sector and the new technology found its way into urban life. In 1813 Westminster Bridge was lit with gas lamps, and a year later the streets of Westminster . In his Description of the Process of Manufacturing Coal-Gas , published in 1815, Accum compared the new form of gas supply with the supply of tap water to households in London since the early 18th century: “With gas it will be possible as often as we can want to have a pleasant light in every room of the house, as is the case with water. ”The translator of the German edition published in Berlin in 1815 felt compelled to explain this analogy for all those readers in Germany who read the did not know the central supply of water: "In England many private houses are set up by pipes etc. routed inside the walls in such a way that one can only open one tap in almost all rooms in order to have water at all times."

In 1814 London had only one gasometer with a volume of 14,000 cubic feet; by 1822 there were four gas companies operating gasometers with a total volume of almost a million cubic feet. In order to keep the pipeline routes as short as possible, the gasometers were installed directly in the residential areas. With this penetration of chemical factories into the residential areas, the first public criticism of the new technology began. This was mainly fed by the repeated explosions and poisoning caused by escaping gas. Accum, who in addition to his work as a chemist also distinguished himself to a great extent as a propagandist of the new technology, took strong action in his publications against the critics of gas lighting. Through a detailed analysis of the causes of the accidents, he showed that the accidents were usually due to the irresponsible use of the technology and could therefore be avoided.

Accum also dealt with the by-products of luminous gas generation early on. The tar residues resulting from the gasification of coal were usually either buried or disposed of in rivers and the sea. In particular, the ammonia- containing residues from gas scrubbing caused lasting damage to the environment. As early as 1820, Accum called for legal measures to prevent these residues from being discharged into sewers and rivers. However, there were no positive reactions to his criticism. The smaller and larger catastrophes caused by gas accidents were evidently more tangible than the long-term environmental pollution caused by the toxic residues from the production of luminous gas.

“There is death in the pot” - fight against toxic food additives

In 1820, Friedrich Accum began the public fight against harmful food additives with his book A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons (German under the title: From the adulteration of food and from kitchen poisons ) . It had been customary for millennia to use vegetable-chemical additives to make foods more durable or to change their taste or appearance. With the advent of industrial manufacturing methods at the beginning of the 19th century, this practice first developed into a problem affecting broad classes. If the production and distribution of food up to then took place largely on the basis of a personal responsibility of the producer towards his customers, this responsibility has been reduced by the increasing centralization of food production. Advances in knowledge in chemistry and the lack of adequate laws to protect consumers made it possible to develop and use new food additives that have not been tested for their harmfulness to humans. Accum was the first to take on this topic and at the same time achieve broad publicity.

Within a month of its publication, all thousand copies of the first edition of A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons were sold. In the same year a second edition was printed in London; two years later a German translation was published in Leipzig. The cover of the English-language editions published in London testifies to Accum's skill in marketing its scientific findings to the public. Framed by intertwined snakes, the book cover shows a rectangle filled with a spider's web, in the middle of which a spider lurks for prey and a skull is attached to the head. Under the skull there is the warning, borrowed from the Old Testament , “There is death in the pot” (“It is death in the pot ”).

In the individual sections of his book, more harmless frauds, such as adding ground dry peas to coffee, alternate with contamination by substances that are massively harmful to health. Accum vividly explained to readers that the high level of lead in Spanish olive oil was caused by clarifying the oil in lead containers and recommended that they use oil from countries such as France and Italy where this practice was not common. He warned against the bright green confectionery that was sold by hawkers in the streets of London, as the so-called "sap green" used for dyeing contained a lot of copper. Vinegar , so the reader learned, is "sometimes copiously adulterated with sulfuric acid in order to give it more acidity."

Accum paid special attention to beer , to which he wrote in the introduction: "Malt beverages, and especially porter , the favorite drink of the residents of London and other large cities, is one of the articles in the preparation of which the greatest frauds are often committed." they learned that substances such as molasses , honey, vitriol , Guinea pepper and even opium were sometimes added to English beer . For today's readers, cultural-historical references are particularly informative, such as the practice of adding Indian Kockelskorns of the Anamirta cocculus to Porter beer, which apparently became rampant especially during the coalition wars and was attributed by Accum to the intoxicating effect of the substance. Accum used a wide variety of sources to back up its claims. As evidence for his statements regarding the Kockelskorn he led z. B. on import statistics and supplemented this with observations on when the grains first appeared in the price quotations of the traders for brewing material and how their price had developed in recent years.

Two other special features characterize the Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons : On the one hand, the focus on general comprehensibility, already known from Accum's earlier writings, whereby Accum explicitly included all chemical analysis methods described in his book. It should be possible for the layperson to understand each sample in the simplest possible way. Accum wrote in the foreword to the first edition:

“In describing the experiments which are necessary to discover the frauds I have indicated, I have endeavored to select only such operations as can be carried out by persons who are not versed in chemistry; And that is also why I believed that I had to indicate all the necessary rules and instructions in the most understandable language, and with the omission of the usual artistic expressions, which the latter would anyway not be in their place in a work that is intended for general use. "

On the other hand, Accum did not limit himself to purely educational work in its fight against toxic food additives. By giving the names of those traders and businessmen who had been convicted of fraud in the years before 1820 at the end of each chapter, he tried to deprive the food adulterers of their livelihood by public exposure and thus actively intervened in London's economic life.

Scandal and trial

Even before the publication of its Treatise , Accum knew that the mention of names from the London business world would meet with resistance and possibly violent reactions . In the foreword to the first edition, he called the publication of the names of fraudulent food adulterators a "seemingly hateful" and "painful duty", which he nevertheless undertakes because it is necessary to confirm his evidence. However, his qualification that he had carefully avoided being named “with the exception of those recorded in parliamentary files and other public reports” did not save him from the anger of his opponents. In the preface to the second edition, he stated that he had received threats. At the same time, however, he affirmed that this did not prevent him from “warning the unwary of the frauds of unscrupulous people, whoever they might be.” In the postscript he added: “On the contrary, I am notifying my hidden enemies that I am in each subsequent edition of this pamphlet will continue to tell posterity the shame which befell the swindlers and dishonorable traders who have been convicted before the bar of public justice for having made food harmful to health. "

A few months after Accum's book on food adulteration began, the events that ultimately led Accum to leave England and return to Germany. For a long time there have been contradicting statements about the exact circumstances. In a study published in 1951, Cole was finally able to use minutes of meetings of the Royal Institution to prove that the representation based on a lexicon entry in the Dictionary of National Biography and later also adopted by the Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie , after Accum, as librarian of the Royal Institution, was in litigation Embezzlement and went to Germany after his acquittal does not correspond to the facts.

The minutes of an extraordinary meeting of the Royal Institution on December 23, 1820, reproduced in full by Cole , show, however, that the events were triggered by an observation by a librarian of the Royal Institution named Sturt. Sturt reported to his superiors on November 5, 1820 that pages had been removed from a number of books in the institute's reading room. These are books that Friedrich Accum read. At the direction of his superiors, Sturt had to drill a small hole in the wall of the reading room in order to observe Accum from the next room. On the evening of December 20, the Minutes went on to say, Sturt was able to watch Accum tear out an article on the ingredients and uses of chocolate from an issue of Nicholson's Journal and take it with him. In one of the magistrates of the city of London on December 21, arranged house search in Old Compton Street actually torn pages have been found, the books of the Royal Institution could be assigned. The minutes of the meeting also read:

“The Magistrate after hearing the whole of the Case observed that however valuable the books might be from which the leaves found in Mr Accum's house had been taken, yet the leaves separated from them were only waste paper. If they had weighed a pound he would have committed him for the value of a pound of waste paper, but this not being the case he discharged him. "

“After hearing the entire case, the magistrate noted that even if the books from which the pages found in Mr. Accum's house came were valuable, the peeled pages were just scrap paper. If they had weighed a pound, he would have paid Accum compensation for a pound of waste paper. But since they weighed less, he dismissed him. "

The Commission of the Royal Institution , which met on December 23, 1820, was not satisfied with this judgment and decided to continue legal action against Accum. As a result, on January 10, 1821, the Times published an open letter in defense of Accum, addressed to Earl Spencer, President of the Institute. Cole suspects that the writer who signed "AC" was surgeon Anthony Carlisle , with whom Accum had been friends since his early years in London. Apparently, Accum's prominent support did not help either, because another protocol from the Royal Institution of April 16, 1821 shows that after initiating proceedings for the theft of paper worth a total of fourteen pence, he was together with two of his friends, the publisher Rudolph Ackermann and the architect John Papworth, who had appeared in court and deposited a total of £ 400 as security. Accum didn't show up at the next court hearing. He had already left England and returned to Germany.

Back in Germany

In the two years before his return to Germany, Accum had published several books with which he continued his work on food chemistry. In 1820 two papers appeared on the production of beer (A Treatise on the Art of Brewing) and wine (A Treatise on the Art of Making Wine) . Culinary Chemistry followed a year later , in which Accum gave practical advice on the scientific basics of cooking, as well as a book on the making of bread (A Treatise on the Art of Making Good and Wholesome Bread) . During his years in Germany, some of his works went through numerous reprints and reached a broad readership in Europe as French, Italian and German translations and also in the United States as reprints.

Immediately after arriving in Germany, Accum went to Althaldensleben . The industrialist Johann Gottlob Nathusius had acquired goods there and used them to set up a large-scale industrial settlement. Between 1813 and 1816, as one of the German pioneers in this field, Nathusius also ran a factory there for the production of beet sugar. Nathusius' extensive library and chemical laboratory probably attracted Accum. However, he only stayed in Althaldensleben for a short time because in 1822 he received a professorship at the industrial institute and at the building academy in Berlin . His teaching activity there in the fields of physics, chemistry and mineralogy was reflected in the two-volume work Physical and chemical composition of building materials, their choice, behavior and appropriate application , which was published in Berlin in 1826. It remained the only work that Accum first published in German.

A few years after moving to Berlin, Accum had a representative house built at Marienstraße 16 (later Marienstraße 23), which he lived in until his death. His last years were marked by a serious gout disease, which eventually led to his death. At the beginning of June 1838 his health deteriorated rapidly and on June 28, around 16 years after his return to Germany, Accum died at the age of 69 in Berlin. He was buried there in the Dorotheenstadt cemetery . The grave has not been preserved.

On the literature and sources

The American agricultural chemist and science historian Charles Albert Browne presented his first biographical sketch of Friedrich Accum in 1925. In ten years of work he had dealt intensively with the life and work of Accum and was able to supplement his study with information from officials and church representatives from Bückeburg. His enthusiasm for the topic went so far that he traveled to Germany in July 1930 and met Hugo Otto Georg Hans Westphal (born August 26, 1873 - September 15, 1934), a great-grandson of Accums. Browne's last essay on the subject was published in 1948 in Chymia , a journal on the history of chemistry, and was largely based on information from Hugo Westphal. Three years later, RJ Cole published an outline of his life, based on English sources, in which he brought new knowledge to light, in particular on the question of the legal proceedings brought against Accum in London in 1821. Both Browne and Cole, however, had little knowledge of the last stage of life Accum spent in Berlin. An overall presentation of Accum's life and work that meets modern standards and that also closes this gap has so far been lacking. It was not without good reason that Lawson Cockroft of the Royal Society of Chemistry in London described Friedrich Accum as one of those chemists who, despite their significant achievements, are largely forgotten today.

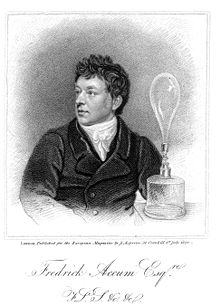

Probably the best known pictorial representation of Accum is a stippling engraving by James Thomson, which was published in the English magazine European Magazine in July 1820 and depicts Accum sitting at a table next to a gas lamp. Thomson's engraving is probably based on an oil painting by the London portrait and history painter Samuel Drummond (1765–1844), which Accum shows in a similar pose and was created a few years earlier. There is also an oil portrait painted by Accum's brother-in-law, the artist Anton Wilhelm Strack , depicting Friedrich Accum as a young boy. Browne claims to have looked at this painting when he visited Accum's descendant Hugo Westphal in Germany. It is more likely, however, that Browne saw a photograph of the picture and that the original was no longer in the family's possession at the time. In 1930 there was also a large bronze profile relief that was formerly attached to Accum's tombstone and whose whereabouts are unclear.

Some papers and documents from the life of Friedrich Accum are now in family hands. A certificate from the Society of Friends of Nature Research in Berlin conferring honorary membership on Friedrich Accum dated November 1, 1814 was made available online in September 2006. A letter from Accum, sent from London to his brother Philipp in Bückeburg, in which the latter gives a very vivid account of life in London after the end of the Napoleonic Wars , is now freely available in the Wikisource project .

List of independent writings and their reprints

- System of Theoretical and Practical Chemistry , London 1803, 2 1807; Reprinted Philadelphia 1808, 2 1813

- A Practical Essay on the Analysis of Minerals , London 1804, new edition expanded to two volumes in 1808 under the title A Manual of Analytical Mineralogy

- An Analysis of a Course of Lectures on Mineralogy , London 1809, expanded edition 1810 under the title A Manual of a Course of Lectures on Experimental Chemistry and Mineralogy

- Descriptive Catalog of the Apparatus and Instruments Employed in Experimental and Operative Chemistry, in Analytical Chemistry, and in the Pursuits of the Recent Discoveries of Electro-Chemical Science , London 1812

- Elements of Crystallography , London 1813

- Practical Treatise on Gas-Light , London 1815, a total of four English-language editions up to 1818, new version under the title Description of the Process of Manufacturing Coal-Gas. For the lighting of streets, houses, and public buildings, with elevations, sections, and plans of the most improved sorts of apparatus. Now employed at the gas works in London , London 1819, 2 1820; German in the translation by Wilhelm August Lampadius as a practical treatise on gas lighting: containing a summary description of the apparatus and the machinery , Berlin 1816, 2 1819; French as Traité pratique de l'éclairage par le gaz inflammable with a foreword and additions by Friedrich Albert Winsor , Paris 1816; Italian as Trattato pratico sopra il gas illuminante: contenente una completa descrizione dell'apparecchio… con alcune osservazioni , Milan 1817

- A Practical Essay on Chemical Re-agents or Tests: Illustrated by a Series of Experiments , London 1816, expanded second edition 1818 under the title Practical Treatise on the Use and Application of Chemical Tests with Concise Directions for Analyzing Metallic Ores, Metals, Soils, Manures and Mineral Waters , 3, 1828; Philadelphia reprinted 1817; French Traité pratique sur l'usage et le mode d'application des réactifs chimiques , Paris 1819; Italian (translation of the second English edition) Trattato practico per l'uso ed apllicazione de'reagenti chimici , Milan 1819

- Chemical Amusement, a Series of Curious and Instructive Experiments in Chemistry Which Are Easily Performed and Unattended by Danger , London 1817, 2 1817, 3 1818, fourth revised edition 1819; German as Chemische Unterhaltungen: a collection of remarkable and instructive products of experiential chemistry , Copenhagen 1819, as Chemische Amusungen Nürnberg 1824; second American edition based on the third English edition with additions by Thomas Cooper, Philadelphia 1818; French in a translation by V. Riffault as Manuel de Chimie Amusante; ou nouvelles recreations chimiques, contenant une suite d'experiences d'une execution facile et sans danger, ainsi qu'un grand nombre de faits curieux et instructifs , 1827, later in a new edition. by AD Vergnaud, last sixth expanded edition Paris 1854; Italian in a two-volume translation as Divertimento chimico contenente esperienze curiose , Milan 1820, second expanded edition in a translation by Pozzi as La Chimica dilettevole o serie di sperienze curiose e instruttive di chimica chi si esequiscono con facilità e sicurezza , Milan 1854

- Dictionary of the Apparatus and Instruments Employed in Operative and Experimental Chemistry , London 1821, reprinted as Explanatory Dictionary of the Apparatus and Instruments Employed in the Various Operations of Philosophical and Experimental Chemistry by a Practical Chemist , London 1824

- A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons: Exhibiting the Fraudulent Sophistications of Bread, Beer, Wine, Spirituous Liquors, Tea, Coffee, Cream, Confectionery, Vinegar, Mustard, Pepper, Cheese, Olive Oil, Pickles, and Other Articles Employed in Domestic Economy, and Methods of Detecting Them , London 1820, 2 1820, 3 1821, 4 1822; Philadelphia reprinted 1820; German in the translation by L. Cerutti as Von der Adulerung der Lebensmittel und von den Küchegiften , Leipzig 1822, 2 1841

- A Treatise on the Art of Brewing: exhibiting the London practice of Brewing, Porter, Brown Stout, Ale, Table Beer, and various other Kinds of Malt Liquors , London 1820, 2 1821; German in the translation by Accum's niece Fredrica Strack Treatise on the art of brewing, or instructions to brew Porter, Braun-Stout, Ale, Tischbier ... , Hamm 1821; French in a translation by Riffault as Manual théorique et pratique du brasseur , Paris 1825, later in a new edition ed. by AD Vergnaud

- A Treatise on the Art of Making Wine , London 1820, then several editions, most recently London 1860; French as Nouveau Manuel complet de la Fabrication des Vins de Fruits , 1827, later also in the translation by Guilloud and Ollivier as Nouveau Manuel complet de la fabrication des vins de fruits, du cidre, du poiré, des boissons rafraîchissantes, des bières économiques et de ménage… , Paris 1851

- Treatise on the Art of Making Good an Wholesome Bread , London 1821

- Culinary Chemistry, exhibiting the scientific principles of Cookery, with concise instructions for preparing good and wholesome Pickles, Vinegar, Conserves, Fruit Jellies with observations on the chemical constitution and nutritive qualities of different kinds of food , London 1821

- Physical and chemical properties of building materials, their choice, behavior and appropriate application , 2 volumes, Berlin 1826

literature

swell

- Letter from Friedrich Accum to his brother dated April 26, 1816 (digital full-text edition in Wikisource ; at the same time first publication in German).

- AC: Mr. Frederick Accum , in: The Times No. 11140, January 10, 1821, p. 3 (open letter, attributed to Anthony Carlisle ; available online as a digitized version at Wikimedia Commons )

Representations

- Wolfgang Schivelbusch : On the history of artificial brightness in the 19th century , Munich [among other things] 1983, ISBN 3-446-13793-9 (in particular the chapter "Gaslight", pp. 22-54).

- Friedrich Klemm: Accum, Friedrich Christian. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 1, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1953, ISBN 3-428-00182-6 , p. 27 ( digitized version ).

- RJ Cole: Friedrich Accum (1769-1838). A biographical study , in: Annals of Science: the history of science and technology 7, 2 (1951), pp. 128-143.

- Charles Albert Browne: Recently acquired information concerning Friedrich Accum , in: Chymia: annual studies in the history of chemistry 1 (1948), ISSN 0095-9367 , pp. 1-9 (with portrait).

- Charles Albert Browne: Correspondence. Prices as considered by Accum , in: Chemistry and industry review 9 (1931), pp. 444-445 (Contains an incomplete English translation of Friedrich Accum's letter to his brother of April 26, 1816).

- Charles Albert Browne: The life and chemical services of Frederick Accum , in: Journal of Chemical Education 2 (1925), ISSN 0021-9584 , pp. 829-851, 1008-1034, 1140-1149.

Web links

Text output

- Friedrich Accum: A Treatise on adulterations of food, and Culinary Poisons , Electronic full text on the basis of reprinting Philadelphia in 1820, available online at Project Gutenberg .

- Nouveau Manuel complet de la fabrication des vins de fruits, du cidre, du poiré, des boissons rafraîchissantes, des bières économiques et de ménage… , translated from the English by Guilloud and Ollivier, expanded by François Malepeyre (1794–1877), Paris 1851 , available online as a PDF document via Gallica , the French National Library's digitization project.

- Manuel de chimie amusante… , ed. by AD Vergnaud, 3rd revised and expanded edition, Paris 1829, available online from Google Books .

Information about Friedrich Accum

- Information on Friedrich Christian Accum's book Culinary Chemistry , published in London in 1821 , available online from the Kansas State University Libraries Special Collection.

- Frederick Carl Accum - Short biography of Lawson Cockroft, available online as a PDF document on the web server of the library of the Royal Society of Chemistry, London.

Remarks

- ^ Bückeburg City Register , entry from February 22, 1764.

- ↑ Cole, Friedrich Accum , p. 129, suspects that Judith Accum had good social relationships.

- ↑ On the Brande family as pharmacists at the English court, cf. Leslie G. Matthews, London's Immigrant Apothecaries, 1600-1800 , in: Medical History 18, 3 (1974), pp. 262-274, here pp. 269-270; PMC 1081579 (free full text, PDF).

- ↑ Actually, Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts .

- ^ Information from Volker Bär, Berlin, a descendant of Accum, to Frank Schulenburg, Göttingen, in September 2006.

- ^ Cole, Friedrich Accum , pp. 129-130, 1951, in the year Cole's life sketch was published, these cards were in the Banks Collection of the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum .

- ^ Browne, The life and chemical services of Frederick Accum , p. 842.

- ↑ On the early history of the Royal Institution, cf. Morris Berman, The Early Years of the Royal Institution 1799-1810: A Re-Evaluation , in: Science Studies 2, 3 (1972), pp. 205-240.

- ^ Cole, Friedrich Accum , p. 130.

- ↑ Cole, Friedrich Accum , p. 131 mentions On the Separation of Argillaceous Earth from Magnesia , in: Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts 2 (1798), p. 2; An Attempt to Discover the Genuineness and Purity of Drugs and Medicinal Preparations , in: Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts 2 (1798), p. 118; A Historical Note on the Antiquity of the Art of Etching on Glass , in: Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts 4 (1800), pp. 1-4; The Occurrence of Benzoic Acid in Old Vanilla Pods , in: Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts 1 (1802), pp. 295-302; Analysis of New Minerals such as the so called Salt of Bitumen, the Bit-Nobin of the Hindoos , in: Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts 5 (1803), pp. 251-255; On Egyptian Heliotropium , in: Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts 6 (1803), pp. 65-68; Experiments and Observations on the Compound of Sulfur and Phosphorus and the dangerous Explosions it makes when exposed to Heat , in: Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts 6 (1803), pp. 1-7.

- ^ "It was the first text-book of general chemistry written in the English language to be based on Lavoisier's new principles; it is outstanding, also, in that it is written in a popular style, the subject matter being graduated as with a modern text-book. ", Cole, Friedrich Accum , p. 130.

- ^ The position of MD George that Rowlandson could have caricatured Accum with the man in the lower left corner is reported by Cole, Friedrich Accum , pp. 131-132. George's thesis was refuted by R. Burgess: Humphry Davy or Friedrich Accum: a question of identification , in: Medical History 16.3 (1972), pp. 290-293; PMC 1034984 (free full text, PDF).

- ^ Cole, Friedrich Accum , p. 132 quotes the full wording of the advertisement. The advertisement appeared in the Times of January 6, 1809, item 7562.

- ^ Frederick Accum: Analysis of the lately discovered mineral waters at Cheltenham; and also of the medicinal springs in its Neighborhood , Phil Mag 31 (1808): 17; Analysis of the Chalybeate Spring at Thetford , Phil Mag 53 (1819): 359-60; see also: Christopher Hamlin: A Science of Impurity. Water Analysis in Nineteenth Century Britain. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles 1990, ISBN 0-520-07088-7 , p. 52-55, 61-65.

- ↑ Schivelbusch, Lichtblicke , pp. 16-17.

- ↑ Schivelbusch, Lichtblicke , p. 23.

- ↑ "Do you mean to tell us that it will be possible to have a light without a wick?", Quoted from Schivelbusch, Lichtblicke , p. 22.

- ↑ Accum's statements made before a committee of the British House of Commons on May 5 and 6, 1809 are reproduced in excerpts in Browne, The life and chemical services of Frederick Accum , pp. 1009-1011.

- ↑ Practical treatise on gas lighting , Berlin edition no year (1815), here quoted from Schivelbusch, Lichtblicke , p. 33.

- ↑ Schivelbusch, Lichtblicke , p. 36.

- ↑ See Schivelbusch, Lichtblicke , pp. 38–44.

- ↑ Akoš Paulinyi , Gasanstalten - die Großchemie in Wohnviertel , in: Akoš Paulinyi / Ulrich Troitzsch, Mechanisierung und Maschinisierung 1600 to 1840, Berlin 1991, pp. 423–428, here p. 427.

- ↑ Owen R. Fennema: Food additives - an unending controversy , in: The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 46 (1987), pp. 201-203, here p. 201, available online as a PDF document.

- ↑ On the adulteration of food and kitchen poisons , Leipzig 1822, preface to the second edition, p. Xxiii.

- ↑ Second Book of Kings , Chapter IV, verse 40; In the wording of the Luther Bible of 1912: “And when they poured it out for the men to eat, and they ate some of the vegetables, they shouted and said: O man of God, death in the pot! because they couldn't eat it. "

- ↑ On the adulteration of food and kitchen poisons , Leipzig 1822, pp. 222–223.

- ↑ On the adulteration of food and kitchen poisons , Leipzig 1822, pp. 214–215.

- ↑ On the adulteration of food and kitchen poisons , Leipzig 1822, p. 211.

- ↑ On the adulteration of food and kitchen poisons , Leipzig 1822, p. 97.

- ↑ On the adulteration of food and kitchen poisons , Leipzig 1822, pp. 104-105.

- ↑ On the adulteration of food and kitchen poisons , Leipzig 1822, preface to the first edition, p. Xxii.

- ↑ On the adulteration of food and kitchen poisons , Leipzig 1822, p. Xxi.

- ↑ On the adulteration of food and kitchen poisons , Leipzig 1822, pp. Xxi – xxii.

- ↑ On the adulteration of food and kitchen poisons , Leipzig 1822, p. Xxiv.

- ^ Dictionary of National Biography , Volume 1, London 1885; A reference to this erroneous article last appeared without comment in the bibliography of the entry on Friedrich Accum in the New German Biography from 1953.

- ^ Alphons Oppenheim: Accum, Friedrich . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 1, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1875, p. 27.

- ↑ Cole, Friedrich Accum , pp. 137-138; these are Minutes 1 and 2 of an extraordinary session on December 23, 1820 chaired by Charles Hatchett , Vice-President of the Royal Institution .

- ↑ The Times No. 11140 of January 10, 1821, p. 3, available online as a digitized version from Wikimedia Commons .

- ^ Cole, Friedrich Accum , p. 140.

- ↑ In the wording: "Mr Moore reported that a Bill of Indictment had been preferred at the last January Westminster Sessions against Frederick Accum for feloniously stealing and taking away 200 pieces of paper of the value of ten pence, and also for feloniously stealing and taking away four ounces weight of paper of the value of four pence, the property of the Members of the Royal Institution of Great Britain ", Cole, Friedrich Accum , p. 140.

- ↑ In the minutes of the Royal Institution it says: “Mr Accum thereupon appeared in Court with his two Sureties Randolph [sic!] Ackermann of the Strand, Publisher, and John Papworth of Bath Place New Road, Architect, and entered into the usual Recognizances himself in £ 200, and the Sureties in £ 100 each. ”, Cole, Friedrich Accum , pp. 140–141.

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Mende : Lexicon of Berlin burial places . Pharus-Plan, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-86514-206-1 , p. 93.

- ^ Lawson Cockroft, Why is Accum important? on the website of the Royal Society of Chemistry, London (accessed on September 19, 2006): "Fredrick Accum is representative of a chemist who is largely forgotten these days but nevertheless contributed to important changes in society [...]".

- ^ Browne, Correspondence , p. 445.

- ^ Written information from Volker Bär, Berlin, to Frank Schulenburg, Göttingen, dated September 19, 2006.

- ^ Document of the Society of Friends of Natural Science in Berlin dated November 1, 1814 on Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ Friedrich Accum to Philipp Ernst Accum of April 26, 1816 in Wikisource.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Accum, Friedrich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Accum, Friedrich Christian (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German chemist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 29, 1769 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Buckeburg |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 28, 1838 |

| Place of death | Berlin |