Gareth Jones (journalist)

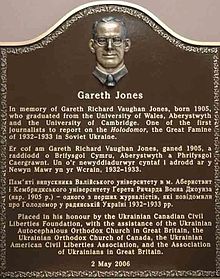

Gareth Richard Vaughan Jones (born August 13, 1905 in Barry , † August 12, 1935 in Manchukuo ) was a British journalist and political advisor .

Life

Gareth Richard Vaughan Jones came from a Welsh family of teachers. His father, Edgar Jones, was the director of the Barry County School, and his mother was the governess of the Hughes industrial family in Ukraine . He was raised multilingual and studied French, German and Russian at the universities of Wales and Cambridge from 1926 to 1929 . From 1930 Jones worked as a policy advisor to former Prime Minister David Lloyd George , whose memoir he also wrote. In the summer of 1931 he visited the Soviet Union with Henry John Heinz II. In Ukraine and Kazakhstan , Jones witnessed the onset of the Holodomor . He immediately wrote a report for the New York Times in which he explicitly named Stalin's forced collectivization of agriculture as the cause of the famine. In 1932/33 he regularly delivered reports from Russia to American, British and German newspapers.

In January and February 1933 Jones reported exclusively for the Western Mail (Wales) on the Nazi takeover of government in Germany. On February 23, he was able to interview Hitler and accompany him from Berlin to Frankfurt am Main in a Junkers Ju 52 / 3m , at that time the fastest and most modern aircraft in the world. Impressed by this experience, he is said to have said: “If the plane crashes, the whole history of Europe would develop differently.” The journalist George Carey judged Jones' relationship to the Nazi state that “Adolf Hitler regarded him as a friend of the reporter ", He was" well networked with the National Socialists and had almost unprecedented access to Hitler and Goebbels ", and he reported" always positive about the achievements of the National Socialists ". Shortly after the flight with Hitler, Jones went to Russia again and on March 7, 1933 boarded a train to Kharkov in Moscow . According to his statements, he got off at a small train station and continued on foot; He described his experiences as follows (excerpts):

“I saw a huge famine. Many people were puffy with hunger. Everywhere I heard sentences like 'We are waiting for death'. I slept on the clay floor next to starving children. In Kharkov I saw people line up at two in the morning in front of shops that didn't open before seven. On an average day, 40,000 people stood in line for bread. Those waiting in line tried so desperately to hold onto their seats that they clung to the belts of those standing in front of them. Some were so weak from hunger that they could not stand without the help of others. "

About two weeks later, Jones returned to Germany and on March 29, 1933, at an international press conference organized by Paul Scheffer in Berlin, informed the world about the extent of the Soviet famine. In addition to many German correspondents, there were press representatives from the Chicago Daily News , The Yorkshire Post , The Sun , Manchester Guardian , Time Magazine , The New York Times and La Liberté . On the same evening or in the next few days, they all published almost identical editorials on the front pages about the famine.

Journalists close to the government in various countries contradicted these representations. In particular, Pulitzer Prize winner Walter Duranty played down Jones' reports. On March 31, 1933 , the New York Times published a denial under the heading “Russians hungry, but not starving” (for example: “Russians are hungry but not starving”) . Duranty described in it that Jones' descriptions were "wishful thinking" and a "great fear story", although there were "serious food shortages" in the Soviet Union, but "no deaths from starvation"; rather, a “widespread disease mortality due to malnutrition, especially in the Ukraine, the North Caucasus and the Lower Volga ” could be determined. On the other hand, Eugene Lyons , the Moscow correspondent for United Press International , noted: “When Jones returned from Russia, he issued notices that were more of a summary of what other correspondents had told him. He reported on excursions to Ukraine, perhaps to emphasize the authenticity of his information, or to protect us journalists other than his main sources from the censors in Russia. "

In fact, Gareth Jones wasn't the first, or the only one, to try to get the subject out there. For example, Paul Scheffer , with whom Jones was friends, as well as Malcolm Muggeridge , William Henry Chamberlin , Hubert Renfro Knickerbocker , but above all delegates of the European Nationalities Congress (ENK) are to be mentioned. This supranational organization learned very early on from the Ukrainian MPs about the procedure and the extent of the famine. From mid-1932 the ENK officially spoke of “systematic murder through hunger in Russia”, organized hunger aid; and encountered massive obstacles from various governments.

At that time, the Soviet government tried to join the League of Nations and actively tried to hide what was happening in Russia from the world community. At the same time, several Western states spoke out in favor of establishing diplomatic and economic relations with the Soviet Union. The USA and Great Britain in particular suppressed negative reporting on Russia from mid-1932 and viewed the publications on the consequences of the so-called starvation exports and the deaths as incitement and propaganda. Maxim Litvinov personally informed Lloyd George in a letter through the Soviet embassy in London that any reports from Jones were undesirable and that further visits to the Soviet Union were prohibited for him. In fact, from now on he did not write any new reports on the famines in Russia. In total, Jones had written twenty articles about it by April 1933, which some newspapers later reproduced without hesitation.

In 1933/34 his sphere of activity was almost exclusively in Germany and Austria. Here he often met in Vienna with Cardinal Innitzer and Ewald Ammende , the Secretary General of the ENK. During a visit to Danzig , Jones met the German Consul General in Kharkov. He thanked him for his journalistic work and noted that the situation for the starving people in Russia was getting worse and worse. During this time, Jones wrote reports mainly for the Berliner Tageblatt , which reflected his closeness to and sympathy for the Nazi regime. About the turn of the year 1934/35 he stayed at Hearst Castle in San Simeon . There he met the media mogul William Randolph Hearst personally at a New Year's reception , on whose behalf Jones wrote articles critical of the Soviet Union in various American newspapers in early 1935. He also charged Josef Stalin with the death of the Leningrad party leader Sergei Mironovich Kirov .

In March 1935 he traveled from the USA via Japan to China. Just as the Soviet Union annexed Outer Mongolia and installed the Mongolian People's Republic as a puppet state , Japan proceeded in Inner Mongolia with the establishment of Manchukuo . The development in the Mongolian People's Republic included Stalin's forced collectivization. As a result, a huge famine and unrest broke out here, too, which the Soviet government countered with an increase in its military presence. Japan saw this as a threat to its interests and also relocated more troops to Manschukuo's border. The official reason given by both aggressors was the support of their “brother countries” in fighting gangs and warlords . From January 1935, the conflicts between Russian and Japanese raiding parties increased dramatically due to unresolved borders, so that the attention of various journalists shifted to the Far East for a short time . None of the conflicting parties had any interest in the clashes becoming known, especially since huge gold and copper deposits had been discovered on Chalchin Gol .

Arrived in China, Jones met the German engineer Dr. Herbert Müller know who, according to later publications, was a camouflaged GPU agent . Together they drove to the crisis area, where they were reportedly abducted by a gang, tortured and detained for 18 days. Allegedly, the kidnappers are said to have demanded a ransom for Germany's release. There is no evidence for these performances, especially since this legend does not mention when and in what form the bandits' demands could have reached the German embassy in Xinjing or Beijing . What is certain is that Gareth Jones was shot in the back of the head shortly before his 30th birthday and that his body was found on August 12, 1935 in Manchukuo's territory.

Aftermath

On August 16, 1935, Paul Scheffer published an obituary in several columns for his friend on the front page of the Berliner Tageblatt , in which he paid tribute to Gareth Jones' work. Later rumors about the involvement of the Soviet secret service, the national Chinese or the Japanese in the death of Jones could not be verified. Because of his reporting on what is now known as the Holodomor , he is now considered a national hero in Ukraine. The Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko awarded him the Order of Merit of Ukraine 3rd Class posthumously in November 2008 .

literature

- Timothy Snyder : Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. CH Beck, 2011.

- Margaret Siriol Colley: Gareth Jones. More Than a Grain of Truth. Newark 2005.

- Deanna Spingola: The Ruling Elite. Trafford Publishing, 2014.

- Ray Gamache: Gareth Jones, Eyewitness to the Holodomor. Welsh Academic Press, 2016.

Movie

Agnieszka Holland dedicated a film to Gareth Jones: Mr. Jones was presented to the public at the 69th Berlinale .

Web links

- Article about Gareth Jones on the website of the Ukrainian Institute for National Remembrance (Ukrainian)

Individual evidence

- ↑ British History, Gareth Jones (Engl. ) , Spartacus Educational Publishers Ltd., accessed on 16 June 2017.

- ↑ Documentary, Gareth Jones , Guardian News and Media Limited, accessed June 16, 2017.

- ^ British History, Gareth Jones , Spartacus Educational Publishers Ltd., accessed June 16, 2017.

- ^ British History, Gareth Jones , Spartacus Educational Publishers Ltd., accessed June 16, 2017.

- ^ Gareth Jones: With Hitler across Europe. The Western Mail and South Wales News, February 28, 1933.

- ^ British History, Gareth Jones , Spartacus Educational Publishers Ltd., accessed June 16, 2017.

- ↑ Timothy Snyder: Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. CH Beck, 2011, p. 52 f.

- ↑ Margaret Siriol Colley: Gareth Jones. More Than a Grain of Truth. Newark 2005, p. 22 f.

- ↑ Famine in Russia? Berliner Tageblatt of April 1, 1933 at garethjones.org, accessed on June 16, 2017.

- ^ Walter Duranty: Russians Hungry, but not Starving. In: The New York Times, March 31, 1933.

- ↑ Deanna Spingola: The Ruling Elite. Trafford Publishing, 2014, pp. 153-156.

- ^ Eugene Lyons: Assignment in Utopia. Transaction Publishers, 1938, pp. 572-580.

- ^ Congress of European Nationalities: The nationalities in the states of Europe: Collection of camp reports of the European nationalities congress. W. Braumüller, 1932, p. 16 f.

- ↑ Ewald Ammende: Does Russia have to go hungry? The fate of people and nations in the Soviet Union. W. Braumüller, 1935, p. 50 f.

- ^ Claudia Breuer: The Russian Section in Riga: American Diplomatic Reporting on the Soviet Union, 1922–1933 / 40. Franz Steiner Verlag, 1995, p. 30 f.

- ↑ Ian Kershaw : Hell Fall: Europe 1914 to 1949. DVA, 2016, p. 111.

- ↑ Ewald Ammende: Does Russia have to go hungry? The fate of people and nations in the Soviet Union. W. Braumüller, 1935, p. 22 f.

- ↑ Timothy Snyder: Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. CH Beck, 2011, p. 20 f.

- ↑ Deanna Spingola: The Ruling Elite. Trafford Publishing, 2014, p. 155.

- ↑ Paul Scheffer: Gareth Jones murdered - shot by his kidnappers. Berliner Tageblatt, August 16, 1935.

- ↑ Short Biography of Gareth Jones (eng.) ( Memento of the original from March 28, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , garethjones.org, accessed June 16, 2017.

- ↑ Reports of the German Embassy in Moscow and the Consulate General Charkow (pdf) , extract from the journal of the SED State Research Association, No. 28/2010, accessed on June 17, 2017.

- ↑ The brave journalist who told the truth about Stalin's famine , Guardian News and Media Limited, accessed June 16, 2017.

- ↑ Deanna Spingola: The Ruling Elite. Trafford Publishing, 2014, p. 155.

- ↑ Europäische Rundschau: Quarterly magazine for politics, economics and contemporary history, Volume 4. Verein Europäische Rundschau, 1976, p. 81.

- ^ Nicole Funck, Sarah Fischer: Mongolia for individual discovery. Verlag Peter Rump, 2015, p. 367.

- ↑ Ikuhiko Hata: Reality and Illusion. The Hidden Crisis between Japan and the USSR 1932-1934. Columbia University Press, 1967, p. 133.

- ↑ Gerald Mund: East Asia in the mirror of German diplomacy: the private-service correspondence of the diplomat Herbert v. Dirksen from 1933 to 1938. Franz Steiner Verlag, 2006.

- ↑ The brave journalist who told the truth about Stalin's famine , Guardian News and Media Limited, accessed June 16, 2017.

- ↑ Paul Scheffer: Gareth Jones murdered - shot by his kidnappers. Berliner Tageblatt, August 16, 1935.

- ↑ Terry Breverton: Jones, Gareth Richard Vaughan Jones. In: Wales A Historical Companion. Amberley Publishing Limited, 2009; P. 33.

- ↑ Documentary, Gareth Jones (Engl. ) , Guardian News and Media Limited, Retrieved on June 16, 2017.

- ^ Jones: The man who knew too much (Report November 13, 2009) , BBC History Information, accessed June 17, 2017.

- ↑ Decree of the President of Ukraine No. 1057/2008 of November 19, 2008; accessed on February 16, 2018 (Ukrainian)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Jones, Gareth |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Jones, Gareth Richard Vaughan (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Welsh journalist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 13, 1905 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Barry |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 12, 1935 |

| Place of death | Manchukuo |