History of Aviation in Australia

The history of aviation in Australia is closely linked to Australian history . As everywhere in the world, there was a movement of technology-loving pioneers at the beginning of the 20th century. In World War I Australian pilots fought on the side of the British Empire and changed in the 1920s, often in civil aviation. Since Australia is characterized by large distances between settlements and cities, the expansion of a dense network of flights played an important role in developing the continent in the course of the 20th century. The Flying Doctors are a case in point.

Pioneering time

Balloons

Balloon rides began in Europe in the late 18th century. However, balloons were not shipped to Australia for a long time and only remained theoretically known there until the middle of the 19th century. In 1851 the English doctor and politician William Bland , who was deported to Australia, devised an airship-like device. The atmotic ship should be able to fly steered like a zeppelin . He sent designs to the world exhibitions in London and Paris in 1852 and 1855. The inexactly worked out plans of the versatile inventor were not put into practice.

After Pierre Maigre's idea of a French balloon failed in December 1856, the Englishman William Dean took off near Richmond in the Australasia gas balloon on February 1, 1858 and drove several kilometers, which was the first manned flight in Australian history. His partner CH Brown had to jump off so the balloon could take off. Two weeks later, Brown also took the balloon, followed by night flights and balloon flights near Sydney . Other balloonists toured South and East Australia in the following years. On April 14, 1879, the artist Henri L'Estrange's balloon crashed near Melbourne, whereupon this survived Australia's first documented successful parachute jump . In 1901 the British Army demonstrated a military balloon in Australia.

Gliding

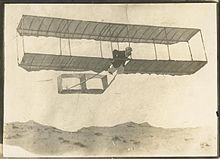

The rich explorer, astronomer and inventor Lawrence Hargrave experimented on his site near Sydney around 1890 with various flight models, including unmanned ornithopters and kites, whereby the box kite he invented proved to be a stable platform, and in November 1894 it was about 5 meters above the ground raised. Hargrave also invented a primitive rotary engine . He carried out experiments with curved airfoils and published his research, but he rejected any form of patents. The principle of the box kite was soon used for (unmanned) meteorological measurements, and can also be seen in later early aircraft, including those of the Wright brothers, who carried out the first powered flight in the USA in 1903. Building on Hargrave's findings, the Australian journalist and amateur technician George Augustine Taylor constructed a glider which he presented on December 5, 1909. Among the many people who tested the single-seater was his wife, Florence Mary Taylor, who became Australia's first female pilot. However, he gave up his plans to build a powered airplane.

Powered flight

After the first flight successes in Europe, the Australian government offered a price of 5000 dollars in 1909 for the invention of an aircraft that was suitable for military purposes. The conditions were high: it should be built in Australia, carry two people, travel at least 20 miles an hour, stay in the air for at least 5 hours , and at least be able to turn in a wide arc. Numerous inventors, from Australia as well as from other countries, failed at these tasks or their results were declared invalid.

The first airworthy Australian powered aircraft was finally built by the engineer John Robertson Duigan , who did not register it for the tender, so the prize money was never claimed. Its first flight took place on July 16, 1910; he had built the two-seater himself, only the engine came from another Melbourne engineer. Duigan, who returned to England, there to make his pilot's license, later became a fighter pilot in the First World War .

Even before Duigan's flight, the first flights and flight attempts on the Australian continent took place with tested imported machines of far better quality than Duigan's amateur work: The experienced Brit Colin Defries took off several times in December 1909 in Sydney and was thus the first person in Australia to successfully lifted into the air on December 9, 1909 with a motor-powered aircraft, a Wright Model A. Since there were several unsuccessful take-offs and crash landings, he was not given the corresponding recognition. The Australian Ralph Banks acquired the Wright machine from Defries, but on March 1, 1910, he barely survived its first launch. The South Australian businessman Frederick H. Jones had imported a Blériot XI and hired technicians Bill Wittber and Frederic C. Custance to assemble it at Bolivar near Adelaide . Nobody in his team had any flying experience, and Wittber did not take off on March 13 because of a disruption. His assistant Custance allegedly made an unobserved night flight, succeeded on March 17 under witnesses, but ended in a crash landing. Later Wittber and Jones also claimed the flight for themselves.

However, it is undisputed that the magician Harry Houdini flew a Voisin Standard in front of a large audience in Victoria on March 18, 1910 and repeated this several times. This went down in history as the first controlled Australian powered flight.

In the years that followed, many Australian inventors produced their own aircraft, the majority of which were unfit to fly, and other importers came into the country (including Blériot and the British and Colonial Airplane Co.) who hoped to do lucrative deals with the government or other business partners. In addition to the technology enthusiasts, stunt pilots and flight artists were an essential part of the scene, who were also known as Barnstormers (for example: barn stormers ). In such artistic air shows and races there were always accidents, which the press commented rather critically after earlier cheering articles.

In 1911, the Australian Douglas Mawson tried to fly a single-engine aircraft in Antarctica, a Vickers REP monoplane . However, the aircraft was already destroyed in Australia and only used as a transport sled in Commonwealth Bay in Antarctica.

First flight schools and pilot licenses

From 1911 onwards, it was recognized that formal training was required for the control and maintenance of the failure-prone machines, and many aviation enthusiasts attended English flight and engineering schools. The first Australian with an official pilot's license was Arthur Longmore, who took his exam in England on April 25, 1911. In Australia itself, meanwhile, an aviation league was founded, which examined the dentist and private pilot William E. Hart in November 1911 and awarded him a pilot's certificate. This was recognized in England in March 1912, making Hart the first pilot to enjoy training in Australia and the fourth Australian with a pilot's license. Hart had already founded his own flight school and won a race to which he had been challenged. In September 1912, however, he was seriously injured in a crash, gave up flying and resumed his work as a dentist. His flight school was later used by the French pilot Maurice Guilleaux. Guilleaux set a record in July 1914 when he carried out the longest mail flight to date from Flemington (Melbourne) to Sydney.

Also in 1914 Harry Hawker and Harry Kauper returned to Australia after three years of training as pilots and mechanics in England. In February 1914 they offered passenger flights with their two Sopwith tabloids in Melbourne for a fee . These included Senator and Secretary of Defense Edward Millen, who became Australia's first politician in the air.

This was followed by the establishment of further flight schools, for example the Queensland Volunteer Flying Civilians in Brisbane in November 1914 and the NSW School of Aviation in New South Wales in 1916. In November 1917, William Stutt made a flight from Sydney to Melbourne and back to ensure the safety of the Aircraft to prove.

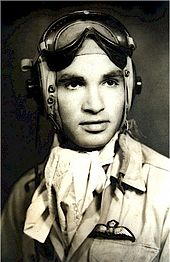

First World War

Preparations for World War I accelerated the aviation industry in Europe, and pilots were also recruited in Australia. As early as 1911, the glider pioneer Taylor had advertised military aircraft. On October 22, 1912, the Australian Flying Corps was founded with five machines. The first and only until 1925 military flight school in Australia started operations in August 1914 in Point Cook near Melbourne with four flight students. The flight instructors were pilots Henry Petre and Eric Harrison, who were assisted by four mechanics. The student pilots were Richard Williams , later known as the Air Marshal as the "father of the RAAF", as well as T. White, D. Manwell and G. Merz. After Great Britain, Australia was the second country in the British Commonwealth with an air force, the Australian Aviation Corps (AFC).

After the outbreak of World War I, the British government in India requested the AFC for the first time in February 1915. Four pilots under the command of Petre set off for Basra and arrived there at the end of May. With the Farman aircraft placed there, the troops were supposed to break through the Turkish lines and carry out reconnaissance and sabotage missions. The Australian-Indian command came to be known as Mesopotamia Half Flight - half flight because the aircraft could only return to their starting position with favorable winds. The planes were hardly adapted to the desert climate of today's Iraq, and four of the five pilots were captured or killed by German and Turkish troops over the course of a year, and the machines were requisitioned for the German military. The first pilot shot down was Captain Merz.

As the only pilot remaining in the Mesopotamia Command, Petre was ordered to Egypt, where he joined the No. 1 squadron of the AFC, which had arrived there in March 1916, under the command of Colonel Reynolds. This squadron was placed under the command of the Royal Flying Corps in September 1916 and was given the designation "Squadron 67" to avoid confusion. Major Richard Williams became the unit in command in 1917. A total of four AFC squadrons took an active part in World War I and continued to be deployed in Egypt and Palestine as well as on the Western Front. Numerous Australian and New Zealand pilots volunteered in the First World War. Not all of them served in the AFC, but more than 200 were incorporated into the UK RFC. Conversely, not all members of the AFC were Australians, but there were also New Zealanders and Englishmen.

In the winter of 1916–1917, the Australian pilot Sidney Cotton developed the Sidcot Suit . He performed patrol flights in the English Channel and was later used as a bomber pilot. His flying suit protected against hypothermia and was used in civil and military aviation until the 1950s.

79 Australian fighter pilots emerged from the First World War as "flying aces", that is, with at least five kills. Pilots with at least 20 kills and selected aviators are listed below.

| Surname | air force | Kills | Awards | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robert Alexander Little | RNAS , RFC | 47 | DSO , DFC , Croix de Guerre | died on May 27, 1918 in action |

| Roderic Dallas | RNAS, RFC | 39 | DSC , DSO, Croix de Guerre | died on June 1, 1918 while on duty |

| Harry Cobby | AFC | 29 | CBE , DSO, DFC | |

| Elwyn Roy King | AFC | 26th | DSO, DFC | |

| Alexander Pentland | AFC | 23 | MC , DFC, AFC | |

| Edgar McCloughry | AFC | 21st | CB , CBE, DSO, DFC | |

| Richard Minifie | RNAS | 21st | DSC | |

| Edgar Charles Johnston | AFC | 20th | DFC | |

| Arthur Coningham | RFC / RAF | 14th | DSO, MC, DFC | later Air Marshal (Lieutenant General) of the RAF |

| Ross Macpherson Smith | AFC | 12 | KBE, MC, DFC, AFC | later aviation pioneer |

| Herbert Joseph Larkin | RFC | 11 | DFC, Croix de Guerre | founded the airline LASCO and the Larkin Aircraft Supply Company |

| Adrian Cole | AFC | 10 | CBE, DSO, MC, DFC | also flew missions as Air Vice Marshal of the RAAF in World War II |

| Stanley Goble | AFC | 10 | CBE, DSO, DFC, Croix de Guerre | later Vice Air Marshal of the RAAF |

| Peter Drummond | RFC | 8th | KCB, DSO, OBE | stayed in Great Britain, later Air Marshal of the RAF |

| George Jones | AFC | 7th | KBE, COB, DFC | later Air Marshal of the RAAF |

| Paul McGinness | RFC | 7th | DFC | later aviation pioneer, founded QANTAS with Hudson Fysh |

| Garnet Malley | AFC | 6th | MC, AFC | advised Chiang Kai-shek on aerial combat strategies in the 1930s |

| Hudson Fysh | RFC | 5 | CFU, DFC | later aviation pioneer, founded QANTAS with Paul McGinness |

| Les Holden | AFC | 5 | MC, AFC | later aviation pioneer, founded Holden's Air Transport Services |

| Patrick Gordon Taylor | RFC | 5 | MC | later navigator and co-pilot of Charles Kingsford Smith , author, accolade 1954 |

| John Robertson Duigan | AFC | - | MC | Aviation pioneer |

Aviation in the interwar period

Australian politics saw aviation as an important means of developing the continent. Prime Minister Billy Hughes and Defense Secretary George Pearce were staunch advocates of aviation advancement, and after the end of the World War hundreds of pilots and aircraft mechanics trained in AFC and RFC returned to Australia. That was a favorable starting point for a forced development of aviation, but on the other hand it was also a risk if the existing potential of the veterans were not steered into controlled channels.

End of the pioneering age

The most important pioneering achievements of the Australians were mainly long-haul flights. Successful Australian pilots often used their exploits as publicity to raise capital and establish airlines. As early as June 1919, the former fighter pilot Nigel Borland Love was preparing an airfield in Mascot near Sydney, which was already the starting point for passenger flights to Melbourne in 1920. Other pilots hired themselves as service providers for pleasure flights and air shows, or carried out flight competitions - the time of the "Barnstormers" returned again, but now with more sophisticated technology.

Keith and Ross Smith first flew a plane from London to Darwin in just 28 days in 1919 , for which they received prize money of $ 10,000 and a title of nobility. Bert Hinkler set a non-stop world record in 1920 with his London- Turin flight.

In the mid-1920s, the adventurous era of the “Barnstormers” came to an end and the pioneer aviators also professionalized themselves in the course of the institutionalization of aviation. In 1928 Bert Hinkler flew the first solo flight from England to Australia in 15 days and in 1931 (to Lindbergh ) the second Atlantic crossing in a solo flight. Charles Kingsford Smith and his co-pilot Charles Ulm in turn planned and flew the first trans-Pacific flight from Oakland to Brisbane in 1928 as well as the first non-stop crossing of Australia and in 1930 the first North Atlantic flight from Ireland to Newfoundland . In 1928, the Australian polar explorer Hubert Wilkins crossed the Arctic Ocean by plane from Point Barrow in Alaska to Spitsbergen . The long-haul flights for which the Australians became famous also claimed victims: Hinkler, Ulm and Smith were killed in such ventures in 1933, 1934 and 1935.

The first female Australian pilot was Millicent Bryant , who took her exam in 1927. In the 1930s women were hardly represented among the pilots, but they also set milestones: Maude Bonney acquired her pilot's license because her husband had forbidden her to obtain a driver's license. She was the first female pilot to cross Australia in 1931 and flew the Australia-England route in 1934, and in 1932 she was the first female pilot to circumnavigate Australia by plane and fly solo to Africa in 1937. Freda Thompson became the first female flight instructor in the Commonwealth in 1933 and was the first solo female pilot from England to Australia in 1934. Nancy Bird-Walton was employed as the first female pilot in an airline in the Commonwealth in 1934 and founded an air ambulance service in 1935, where she also worked as a midwife. Bird-Walton became Commander of the Air Force Corps during World War II and founded the Society of Australian Women Pilots in 1950.

Bert Hinkler at the age of 27

Charles Ulm (1928)

Ross Macpherson Smith (around 1919)

Maude Bonney (around 1933)

Nancy Bird-Walton (around 1939)

The last great pioneering company in Australian aviation is the MacRobertson Race of 1934 from London to Melbourne - eleven of twenty machines made it to the finish line, seven teams gave up and two suffered total write-offs. It took the winning team five days to complete the route.

Airship routes

The Imperial Airship Scheme was an initiative of the British Empire to connect all overseas territories via zeppelin routes. The project was promoted from 1921 to 1931 because it initially appeared that rigid airships were superior to aircraft in terms of range and operating costs. The network was expanded to India ( Karachi ) by 1930 , and Australia was to be connected by 1935. The major project dragged on in terms of budget and time. In 1927, the locations for the anchor masts near Perth and Melbourne were still being explored. The accident of the R 101 brought the project to an abrupt end in 1931; Australia was never approached by airships from England.

First civil airlines

The fighter pilot Norman Brearley founded the Western Australian Airlines in 1922, which was allowed to set up the first regular air line between Geraldton and Derby in the structurally weak north-west of Australia under state supervision in November 1922 . WAA was bought by Adelaide Airways in 1936. Also from the north came the beeline QANTAS , which from 1922 operated the second regular beeline in Australia, in the northeast of the country. Founded in 1920, Qantas is now the third oldest airline in the world. QANTAS specialized in connecting routes to the British Empire and also built its own aircraft under British license at the end of the 1920s.

Conversely, airlines were also founded by aircraft manufacturers. The most prominent all-rounder was Larkin with LASCO (Larkin Aircraft Supply Co.), who operated an airline and a flight school at the same time, was an aircraft manufacturer and publisher of a flight magazine. Nigel Love, the earliest airport operator, aircraft manufacturer and flight service provider among the returning World War II pilots, retired from the aviation business in 1923. Butler Air Transport became famous in South Australia in 1922, founded by the former fighter pilot and mechanic Cecil Arthur Butler. MacRobertson-Miller Aviation followed in 1927, but its focus soon shifted from Adelaide to Perth.

The Australian National Airways (ANA), founded with five planes in January 1930 by the famous Charles Kingsford Smith and his co-pilot Charles Ulm, was given up in November 1931 after two total losses. An independent company with the same name (ANA) emerged from a merger of Adelaides Airways and Holyman's Airways and existed from 1936 to 1957. Holyman was an aggressive businessman who also harassed Ansett ( Ansett Australia ), but could not buy it. Holyman's ANA rose to become a dominant domestic airline.

Another important airline was Guinea Airways, a cargo company founded by Cecil John Levien, which operated with German Junkers aircraft in inaccessible areas of New Guinea and made it possible to exploit gold mines there. For a short time it was one of the most profitable airlines in the world and was able to expand to Australia.

A total of 39 airlines existed before the Second World War.

Another chapter in civil aviation history is the Australian Aerial Medical Service, launched in 1928, known as Flying Doctors (RFDS) from 1942 . The medical service founded by John Flynn made it possible to deliver medical care to the sparsely populated rural areas in Central Australia through the use of radio and airplanes.

Civil Aviation and the State

On October 13, 1919, an international agreement on air traffic regulation was signed in Paris, from which the ICAN emerged. This also submitted to Australia, where an air traffic committee had already met on February 25, 1919. In May 1920 it was decided that control of the airspace should lie with the Australian Confederation. The first, still quite simple, Air Navigation Act was passed on December 2, 1920, came into force on March 28, 1921, and was applied for the first time after a transition period of three months.

Colonel Horace Brinsmead was appointed as the first controller of civil aviation on December 16, 1920 . In 1921 he built up a staff of eight, which he divided into three departments. The national planning and construction of airports and runways was taken over by airfield overseer Edgar Johnston . Naturally, his department grew the fastest, since airfields were to be built in all major cities in Australia by 1921, and emergency runways had to be expanded all over the country. EJ Jones, as the air surveillance supervisor, was responsible, among other things, for issuing pilot licenses - the Australian Aero Club had done this by 1922, and numerous licenses were withdrawn. FW Follett became the supervisor for aircraft and their safety and issued badges for aircraft to be renewed annually.

In the mid-1920s, security was permanently increased by the above-mentioned measures of air traffic control. Pilots were now trained for airmail, airfreight and (initially rare) passenger flights, and aircraft were tested for airworthiness. Closed cabins were now the norm and the British Commonwealth was considering establishing a permanent airmail link between England and Australia. On the way to London for negotiations in 1931, Controller Horace Brinsmead had two crashes and was never able to return to duty - this incident proved that safety was still not guaranteed. As Brinsmead's deputy, Edgar Johnston initially took over the position of controller temporarily and officially from May 1934. From 1936 the previous civil aviation supervision was converted into the Civil Aviation Board, but remained subordinate to the Ministry of Defense.

The England-Australia airmail route was finally opened in January 1934: QANTAS flew the mail to India, where it was taken over by Imperial Airways from Great Britain. In 1938 the Commonwealth regulation was relaxed, which promoted air traffic only where there were no railway lines. This meant the end of Cootamundra International Airport - flights from England could now be directed directly to Melbourne and Sydney. Another important decision for the aviation industry had been made as early as 1937: in Australia, aircraft imports were restricted to Commonwealth (i.e. British) aircraft. The only alternative to this was domestic manufacturers, which included manufacturers Larkin (1925–1933) and Butler (1930). At Johnston's instigation, this restriction was relaxed in 1937. This made it possible to import more modern Douglas aircraft (DC-2 and DC-3) from the USA, and many operators, with the exception of British-Imperial airlines, switched their fleets.

A tragic airplane accident occurred on October 25, 1938: an ANA DC-2 was caught in thick fog on its flight from Adelaide to Melbourne and crashed into the flank of Mount Dandenong. Among the 18 inmates were industrial giants from Southwest Australia and a senator. The so-called Kyeema crash resulted in a tightening of safety regulations, in particular the introduction of weather warnings. The previously existing aviation committee under Edgar Johnston came under heavy criticism. In 1939 the body was dissolved and replaced by an aviation authority (Commonwealth Department of Aviation). The agency was chaired by Arthur Brownlow Corbett , who had already made a name for himself as a reorganizer in the postal service. He divided the authority into seven departments. One of his deputies was Johnston, who was assigned the air freight department. Furthermore, the agency was no longer subordinate to the Minister of Defense, but had received its own government department. The first Minister for Air and Civil Aviation was James Fairbairn, who was killed in the Canberra plane crash along with two other cabinet members in 1940 . His successors were Arthur Fadden , John McEwen and from 1941 to 1949 Arthur Drakeford . The two ministries for civil aviation and the air force were not led by different people until 1951.

Military aviation in the interwar period

The Australian Flying Corps AFC existed until 1919 and was dissolved together with the Australian Imperial Force . In 1920 the Australian Air Corps (AAC) was founded. This air force was not to form its own armed forces, but to be added to the army . The reason for this was doubts about the effectiveness of air warfare when it did not operate directly with land forces; There were also fears that the relevant military would lose their competence. Staff officer Richard Williams prevailed against this : he demanded the creation of a new armed force alongside the army and navy. Premier Hughes supported these petitions and in March 1921 the Australian Air Force (AAF) was formed. After the approval of the British King, it was renamed the Royal Australian Air Force, RAAF (about: Royal Australian Air Force) in August.

Richard Williams shaped the RAAF for seventeen years and three terms as Chief of the Air Force, although initially not in the rank of general like his colleagues in the Navy and Army. He traveled regularly to England for training courses in order to implement newer techniques in Australia. After a series of accidents, he was transferred to Great Britain as a contact in 1937, his previous deputy and internal rival Stanley Goble became the new chief of the air force and remained so until 1940.

A notable person in the military development of the British and thus also of the RAAF was Sidney Cotton, who significantly improved photogrammetry . In spy flights over the German Reich , he provided excellent aerial photographs and continued to develop his technology during the Second World War.

Second World War

Australia entered World War II with the rest of the Commonwealth and declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939. Volunteer associations were relocated to the Mediterranean and the Middle East, with around 9% of the RAF being Australian associations. Not entirely surprising, Japan attacked the Allies in Southeast Asia in 1941, and the Australian military now concentrated primarily on the Pacific War and for the first time cooperated more closely with the United States than with the Commonwealth. In the first missions the RAAF was far inferior.

In 1940, Stanley Goble resigned as chief of the Air Force, as his proposals for the formation of expedition pilots in favor of the training plan in the Commonwealth were postponed. He was succeeded by the US-Briton Charles Burnett. Arthur Drakeford was appointed Minister of Air and Minister of Civil Aviation after the government crisis in 1941 that toppled Menzies' government and made John Curtin premier . The economically minded Drakeford relied on the advice of military experts, but set the course in the immediate post-war period until 1949. Drakeford and Burnett clashed frequently. When Burnett demanded drastic personnel changes in the RAAF organization, he was replaced by George Jones in May 1942 . Jones remained in this position until 1952, despite internal conflicts in the RAAF.

Since there was a shortage of pilots and ground personnel, the Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF) was founded in 1941 after 14 months' lead time , which existed until 1947 and in 1944 comprised 18,000 women under the command of Clare Stevenson. While British female pilots from the WAAF flew newly manufactured military flying machines from the factories to the RAF for further use, Australian female pilots did not fly during World War II despite training with the RAAF . This was explained by the fact that there were enough male pilots in Australia and initially no manufacturers of military aircraft in Australia. The RAAF used the WAAAF primarily as ground personnel; for example when packing parachutes, as drivers, maintenance and radar personnel.

The lost battle for Singapore in February 1942 had serious consequences for Australia: Qantas had to discontinue its air service to Great Britain, half of the planes were destroyed. Guinea Airways also lost numerous aircraft and had to withdraw completely from the previous home country New Guinea, where the line could never gain a foothold even after the Second World War. Ansett Australia lost almost all flight routes as it mainly operated internationally - but Ansett managed to secure freight contracts. The fiercest competitor Holyman, meanwhile, dominated domestic air traffic with the ANA. Australia threatened to be cut off from the motherland.

Also in February 1942, Darwin , an important Allied naval base, was bombed by the Japanese . By November 1943, Darwin had been hit by 64 air raids, 33 more targeted the Australian north coast - Darwin was exposed to more violent shelling than Pearl Harbor . The now imminent threat made the Australians more motivated. Many civil aircraft were now used for military supply and cargo flights. As early as 1940, massive investments had been made in expanding flight schools, bases and air forces. The emergency was also a stimulus for aircraft manufacturers who had not been particularly successful in the production of civil aircraft. The British company De Havilland had built its first plants in Sydney as early as 1930, and has been intensifying the production of military machines since 1938. In Australia, De Havilland produced, among other things, Tiger Moth training aircraft, De Havilland DH.84 Dragon transporter, Mosquito - Fighter- bombers and vampire jets. Founded in 1935 by the entrepreneur Essington Lewis ( Broken Hill Proprietary ), the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (CAC) exclusively produced military aircraft ( CAC Wirraway , CAC Boomerang , CAC Woomera ). Finally, there was the DAP (Department for Aircraft Production, such as: Department of Aircraft ), a consortium under the supervision of the government, which licensed British models nachbaute.

The turning point of the Pacific War came in 1943 when the armed forces of the United States, Australia and New Zealand successfully copied Japanese strategy. Important missions of the RAAF were in the Battle of Milne Bay , in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea and in the liberation of the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, Borneo and the Philippines. A deployment in Operation Downfall was also planned.

post war period

RAAF in the post-war period

During the Second World War, 37,000 air troops were trained. The RAAF comprised 174,000 men (most of the ground crews) towards the end of World War II and had a total of 5,600 aircraft. By October 1946, the RAAF had already shrunk to a total of 13,000 men. The RAAF participated in numerous missions after the Second World War: Berlin blockade (1948/49), Korean War (1950–1951), Malaya Crisis ( ANZAM ; 1955–1960), Vietnam War (1964–1971, 1975), East Timor -Crisis (1999), Iraq War (2003-2009), Afghanistan War (since 2007).

Aircraft industry in the post-war period

After the rapid rise in the 30s and 40s, the Australian aircraft industry stagnated and had to specialize in niche products and subcontracting. The state-owned DAP was after the war in GAF ( Government Aircraft Factories , such as: governmental airplane factories ) renamed, privatized in 1987 and later as well as CAC of Boeing bought.

Three smaller aircraft manufacturers in the 1960s to 1980s were Victa, Transavia and Yeoman, who specialized in small and agricultural aircraft.

Two-airline strategy

After the Second World War, there was a quick switch from war pilots and aircraft back to civil aviation. The Labor government established the Two-Airlines Policy (strategy of the two airlines). Domestic flights were now dominated by a private ( Australian National Airlines , ANA, later Ansett Australia ) and a state airline ( Trans Australia Airlines , TAA), while smaller competitors were tolerated. The same models were used and the same prices were charged. Flight plans were compared to the extent that two flights on the same route took off and landed almost in parallel. The leading private provider was given preference by the state supervision, while smaller providers were assigned local routes with many stopovers by the flight regulation at best. This order remained in place until the 1980s.

The state-owned TAA was re-established in 1946 and was run in a market economy and largely independent of the government. The TAA initially pushed into the main routes and from 1949 also offered flights on the structurally weak north coast and from 1960 even to New Guinea. Since it was covered by the government, the TAA was able to modernize faster than the private providers in the 1950s. She used twin- engine aircraft and aircraft with pressurized cabins for the first time . In the late 1950s, jet planes were the norm, jumbo jets appeared in 1970. The ANA was financially weakened by numerous takeovers in the 1950s, and the pace of modernization by the government was slowed.

Ansett Australia, which had mainly operated international flights before the Second World War, was now severely disadvantaged domestically. Ansett then set up his company more broadly and invested in ships, hotels and tourism. After Holyman's death, there were efforts by the shareholders to sell the ANA to the state as well. Reginald Ansett was able to make its own offer, and so Ansett Australia swallowed the larger ANA in 1957 and thus became the dominant private airline in the domestic business. Ansett was also financially stricken, and in 1959 the TAA had to cancel the modern Caravelle aircraft that had already been ordered in favor of older Lockheed models in order to comply with the government's guidelines of the cartel .

International flights were only offered by Qantas Imperial Airways, which was bought out by the government at market price in 1947 and thus nationalized. While there had previously only been regular flights to England with stopovers in India, an airline to Tokyo was set up immediately after the nationalization to supply the Australian occupation forces in Japan. The Qantas management slowly began to detach itself from the British Commonwealth, and now also resisted the pressure to use only British aircraft. 1952 routes were established across the Indian Ocean, especially to South Africa. In 1953, Qantas entered the Pacific business, which until then had been dominated by US companies. From 1958 Qantas offered flights worldwide, including transatlantic flights. This made Qantas one of the first globally operating air travel providers.

The Two Airlines Policy was initiated by Aviation Secretary Arthur Drakeford and Daniel McVey, Director General of the Air Traffic Authority. Fysh supported the government plans, although they resulted in his disempowerment as Qantas boss. Ivan Holyman as head of the ANA and beneficiary of the situation was also very cooperative. Reginald Ansett, who initially always complained about it, is also very satisfied with the situation after the takeover of ANA. From abroad, the two-airline policy was admired as stable and reliable. The legal basis of the cartel was modernized again and again, so in 1978 and 1981 the legal situation was changed in such a way that the small competitors were no longer disadvantaged by the restrictive licensing of airlines and air movements as well as by restrictions on aircraft imports, but rather by being assigned to airport seats. This also marked the beginning of stronger competition between Ansett and TAA, who were now allowed to compete with different aircraft models and flight times. At the end of the 1980s, however, the pseudo competition was increasingly criticized.

Regional aviation in the post-war period

Regional airlines and cargo airlines were only affected by the two-flight strategy to the extent that their options for expansion were severely limited. Numerous regional airlines became subsidiaries or subcontractors of Ansett due to the re-regulation of the market in the eighties. These include Kendell Airlines, Hazelton Airlines, SkyWest Airlines, Aeropelican Airways, Impulse Airlines, Sunstate Airways and Southern Australian Airlines. Other regional airlines like Eastern Australian Airlines and Air Queensland were swallowed up by Australian Airlines (formerly TAA).

The Flying Doctors Service emerged from the Aerial Medical Service in 1942 and was given the addition of Royal in 1955. Initially, the RFDS relied on charter aircraft. Service providers included Qantas (after its nationalization also the TAA) and Connellan Airways. Connellan Airways sold two aircraft to the RFDS in 1965 and provided their pilots until 1973.

During the 1970s, Connellan (renamed Connair) was under increasing financial pressure. On January 5, 1977, former Connair pilot Colin Forman stole a Connair aircraft and drove it into the Connair building in Alice Springs , killing four people, including the founder's son. This is the only known airplane suicide attack in Australia and became known as the Connellan Air Disaster . Connair went bankrupt in 1980.

deregulation

As early as 1990, the government was planning the long-term privatization of Qantas, TAA (renamed Australian Airlines since 1986) and the airports. The permanent establishment of the competing brand Compass Airlines was again prevented by the regulation that assigned Compass the most unfavorable airport locations. In September 1992 Australian Airlines was sold to Qantas and Qantas was privatized in March 1993. In 1996 the last state shares were sold to Qantas.

The departure from the two-airline policy from 1992 and the deregulation led to numerous new national, private passenger airlines being established, as has long been the norm outside of Australia. The Ansett Group survived the opening of the market with some difficulties. Ansett merged with Air New Zealand in 2000 and won a takeover battle for Hazelton Airlines against Qantas in early 2001. This weakened considerably, Ansett went abruptly bankrupt shortly after September 11, 2001 , which caused great chaos at the airports. Ansett flights could only barely be covered by other lines. Most of the subsidiaries and subcontractors did not survive 2001.

The airline Virgin Blue , which was founded in 2000 and was the first major airline to offer nationwide connections and, after Qantas, was the second largest airline in Australia in 2011 , particularly benefited from this . In 2011, Virgin Blue was renamed Virgin Australia . Ansett's bankruptcy in 2002 enabled its well-positioned subsidiaries Kendell Airlines and Hazelton Airlines to merge under the name Regional Express Airlines (rex), which in 2011 was the largest regional airline in Australia. The competition from Virgin Blue and rex led Qantas to found its own low-cost airline, Jetstar Airways and the QantasLink brand, which brings together several regional airlines .

Timeline

Museums

Aviation is an integral part of Australian culture and history. Many Australians are proud of the achievements that were made in their country, especially during the pioneering days. Accordingly, there are numerous museums, organizations and associations that are dedicated to the topic or just individual aspects. General museums with aviation departments are not included in the list below.

Without specialization:

- Australian Aviation Museum in Sydney-Bankstown, New South Wales ( Link )

- Australian National Aviation Museum in Melbourne-Moorabbin, Victoria ( Link )

- Civil Aviation Museum in Melbourne-Essendon, Victoria ( Link )

- Lincoln Nitschke Aviation Museum in Greenock, South Australia ( Link )

Specialized in classic cars:

- Aircraft Restoration Society History Museum in Albion Park, New South Wales ( Link )

- Australian Glider Museum in Melbourne-Mount Waverly, Victoria ( Link )

Dedicated to the military or the RAAF:

- Point Cook RAAF Museum near Melbourne, Victoria ( Link )

- Temora Flight Museum in Temora, New South Wales ( Link )

- Naval Aviation Museum in Nowra, New South Wales ( Link )

- Ballarat Aviation Museum in Ballarat, Victoria ( link )

- Camden Aviation Museum in Narellan, New South Wales ( Link )

- Fighter Jet Museum in Adelaide, Southern Australia ( Link )

- RAAF Flight Heritage Museum in Bull Creek, Western Australia ( Link )

- Fighter Jet Museum in Melbourne-Williamstown, Victoria ( Link )

- Tocumwal Airport Museum in Tocumwal, New South Wales ( Link )

- RAAF Aviation Museum in Wagga Wagga, New South Wales ( Link )

- RAAF Aviation Museum in Townsville, Queensland ( Link )

- Australian Military Aviation Museum in Oakey, Queensland ( Link )

- Caboolture War Aircraft Museum in Caboolture, Queensland ( Link )

- Lake Boga Flying Boat Museum in Lake Boga, Victoria ( Link )

Dedicated to a single airline or person:

- Qantas Foundation Museum in Longreach, Queensland ( Link )

- Ansett Museum in Hamilton, Victoria ( Link )

- TAA Museum in Melbourne, Victoria ( Link )

- Hinkler Aviation Museum in Bundaberg, Queensland ( Link )

Dedicated to a single state:

- Queensland Aviation Museum in Caloundra, Queensland ( Link )

- Center for the Australian Aviation Heritage in Darwin-Winnellie, Northern Territory ( Link )

- Central Australian Aviation Museum in Alice Springs, Northern Territory ( Link )

- South Australian Aviation Museum in Adelaide, Southern Australia ( Link )

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Airship Honor for Australia - Bland's remarkable invention more than 70 years ago. The Argus, September 13, 1924

- ↑ Summary of early aviation in Australia ( Memento from January 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Biography of Lawrence Hargrave (English)

- ↑ George Augustine Taylor's biography

- ↑ Florence Mary Taylor's biography

- ↑ Biography of John Robertson Duigan (English)

- ↑ reconstructed views of Duigan's "Pusher Biplane"

- ↑ Summary and evaluation of the first flights in Australia. Royal Aeronautical Society ( Memento from January 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), (PDF; 109 kB)

- ↑ Who was the first to fly in Australia? ( Memento from January 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c Establishment of the Civil Aviation Authority

- ↑ antarctica.gov.au : History of Australian Antarctic aviation. Aviation: 1947 , in English, accessed November 9, 2011

- ↑ Biography of Sir Arthur Longmore

- ^ Biography of William E. Hart

- ^ Robert Lee, 2003: Linking a Nation: Australia's Transport and Communications 1788-1970. University of Western Sydney

- ↑ Harry Hawker biography

- ^ Biography of Henry Alexis Kauper

- ^ History of the AFC ( Memento of March 11, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Sidcot pilot suit ( Memento of the original from January 15, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on vafm.org (English). Retrieved January 14, 2015

- ↑ Coningham was a native of Australia, but grew up in New Zealand and considered himself a New Zealander.

- ^ Biography of Nigel Borland Love

- ↑ Pioneers of Australian Aviation

- ↑ Australian female pilots ( Memento of the original from November 18, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Review article on the Imperial Airship Program

- ↑ Poskod.SG: Airship Dirigible Singapore dreams and disasters. , Article from October 20, 2011, accessed on May 25, 2013 ( Memento of the original from June 10, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Imperial Airship Bases, February 10, 1927

- ↑ Development of air transport in Australia ( Memento from January 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ TAA Museum: Two Airlines Policy

- ^ Establishment of the civil aviation authority

- ↑ Malcolm Brown, Harriet Veitch: Walton, Nancy-Bird (1915–2009) on oa.anu.edu.au (English). Retrieved January 12, 2015

- ↑ RAAFMuseum, The Heritage Gallery. WAAAF and WRAAF. Retrieved January 12, 2015

- ^ Bombing of Darwin ( Memento April 8, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b aircraft construction in Australia

- ↑ Consideration of the two-airline policy ( memento of the original from February 25, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.