Hartmann II of Grüningen

Hartmann II. Von Grüningen (* before 1225 ) was a Count of Württemberg who was enfeoffed as an Imperial Storm Ensign ("Signifer Imperii") with the Burgraviate and the city of Grüningen , today Markgröningen . Together with Ulrich I of Württemberg he had placed himself in the service of the Pope and the opposing kings in order to take away the Swabian ducal dignity and their royal estates in the Swabian lowlands from the Hohenstaufen . He wanted to develop Grüningen, which the Staufers had elevated to the status of an imperial city, to become his royal residence. Ulrich pursued the same goal with Stuttgart.

Hartmann I. or Hartmann I. + Hartmann II. + Hartmann III. ?

There is the hypothesis that there were father, son and grandchildren, all of whom were called Hartmann von Grüningen and that modern historical research wrongly combined them into one person, the father Hartmann I. von Grüningen . The present article about Hartmann II. Therefore contradicts the article about Hartmann I. von Grüningen. The article on Hartmann III is also based on the assumption of the three Hartmanns. from Grüningen .

Origin and claims

Traditional claim to Grüningen

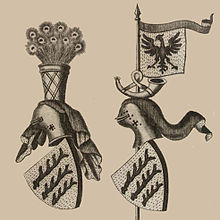

The right of action , the imperial storm flag and the associated Grüninger royal fief (burgraviate and commune) are said to have been reserved and inheritable to Swabian followers since Charlemagne. The office and fiefdom seemed prominent enough that the Counts of Maden , for example, named themselves after them, although they owned far more possessions elsewhere: From Count Werner IV. Von Grüningen , who was a close relative of the first verifiable Wuerttembergian Konrad von Württemberg and died in 1121 without descendants , the Wuerttemberg counts evidently derived the claim to the imperial storm flag, castle and city of Grüningen, which was always pursued with great energy.

In 1139, King Konrad III of the Staufer . held a court day in the Grüninger Königspfalz and registered for the Denkendorf monastery . Among the witnesses were Count Ludwig and Emicho from Württemberg . Konrad may have handed over the previously held office of Reichssturmfähnrichs to one of the two. After that, there is another Wuerttemberg pair of brothers in the Staufer entourage: Count Hartmann I and Ludwig II of Wuerttemberg. Konrad von Württemberg stands out among their descendants, because he apparently renamed himself "Count Konrad von Grüningen" after receiving the Grüninger imperial fief and was the first well-known Württemberger to have the Veringer stag in his coat of arms. He accompanied Emperor Friedrich II on his crusade and wrote a document in Acre in 1228 for the benefit of the Teutonic Order. In the absence of further documents, it is assumed that he did not return from the "Holy Land". In his place, his brother Hartmann I von Grüningen appears presumably as a Reichssturmfähnrich in the emperor's suite. It was first documented in 1237 together with his grandfather Hartmann I. von “Warteberch” (Württemberg) in the field camp near Augsburg.

Own property in Grüningen

As church lords and owners of the “Herrenhof”, the Württemberger Counts of Grüningen had their own property in Grüningen in addition to the church. This is evidenced by what is probably the oldest coat of arms carved in stone from “the old counts” on the preserved base of the former “stone house”, where the rectory was built in the 16th century.

An unknown or a renamed brother of Ulrich?

The first reliable reference to Hartmann II comes from September 30, 1246, when Count Hartmann I von Grüningen was first called "the elder". Probably Hartmann II was not his son, but one of the nephews of the first Hartmann von Grüningen named as heir in 1243. In April 1243 he sold the "Grafschaft im Albgau" in Capua along with the Eglofs castle with people, possessions and all accessories to Emperor Friedrich II. The purchase price of 3200 silver marks to be paid in installments - or the town of Esslingen serving as a pledge - should be in case ignore his premature death of his nephew, the Count of Württemberg because of the Reich Striker Ensign bound in the imperial entourage Hartmann I. apparently had no heirs.

The nephews who are entitled to inheritance are presumably the brothers Ulrich and Eberhard von Württemberg, who previously documented this together. Since Ulrich then only appears solo and Eberhard no longer performs at all, it would be possible that Eberhard would change his name after an inheritance was divided in order to take over Hartmann I's inheritance as Hartmann II von Grüningen. Especially since Ulrich and Hartmann acted like brothers in close coordination from 1246 and Hartmann II took over the guardianship of his sons Eberhard and Ulrich after Ulrich's death.

However, since most historians refer to the two as cousins, cousin Hartmann II must have acted in parallel before 1246 or not yet have legal capacity. However, there is no document that could prove this. There is also no evidence of Hartmann the elder after 1246. It is therefore quite possible that Hartmann I died in 1246 or withdrew and Eberhard alias Hartmann II took over his inheritance, while Ulrich became the sole heir of the Württemberg line.

expansion

Change of sides in the throne dispute

After the Staufer had elevated Grüningen to an imperial city in 1240, the fiefdoms were asked to implement its expansion. Hartmann I had already taken the first steps, such as the establishment of the Heilig-Geist-Spital . With papal money, the prospect of Staufer property and the promise of being able to inherit the Hohenstaufen as Dukes of Swabia, Ulrich and him had moved him, immediately before the decisive battle on the Nidda against Landgrave Heinrich Raspe, who had been raised against Pope Innocent IV IV. To change parties with around 2000 Swabian followers. So they turned the tide and forced the supposedly superior Staufer King and Swabian Duke Konrad IV to flee. Hartmann was then largely able to keep Konrad away from Lower Swabia. A third Württemberger "Grafenspross" named Heinrich He was rewarded for his loyalty to the Pope with the bishopric of Eichstätt, which fell vacant in 1246 . At the same time a "Hermann von Grüningen" canon of Eichstätt and the cathedral bailiwick were transferred to the Counts of Württemberg.

Ulrich and Hartman often signed documents together and stayed several times with the Pope in his exile in Lyon . They were soon among the most influential Swabian counts. Ulrich expanded in the Rems Valley and was also able to secure the county of Urach, which had fallen back to the opposing king. Hartmann, on the other hand, seemed to concentrate on the regions north of Stuttgart. Beyond Grüningen, he increasingly acted in the Marbach / Steinheim / Oberstenfeld area and probably also founded the city of Brackenheim on the northern border of his sphere of influence.

Princely residence city

In 1252, the Comes Illustrissimus (high born), called Hartmann, was able to assert at the Imperial Assembly in Frankfurt that the second anti-Staufer King Wilhelm of Holland confirmed to him the imperial storm flag, castle and city of Grüningen "peculiar" ( Heyd ) as inheritance "with all justice". The urban expansion of Grünigen, which was initiated by the Staufers, was continued with the construction of a new castle and the establishment of the Heilig-Geist-Spital . In addition, as the lord of the church, he also started building the new Bartholomew Church from Carolingian times and converted the Romanesque basilica into one of the first Gothic churches in southern Germany - at that time the largest sacred building in Württemberg. That he ran out of money more and more is shown by the more economical design of the church with increasing construction progress and the numerous property sales in the Oberland, which did not stop at the marriage property of his wife Hedwig von Veringen and therefore required her approval.

Expansion in the lowlands

Hartmann II always boasted of his constant loyalty to the Pope , emphasizing that, unlike other Swabian aristocrats, he had never been in the Staufer service and, unlike Ulrich von Württemberg, did not compromise with the Staufer party. However, he was denied the promised ducal dignity even after the death of Conrad IV (1254) and also after the early death of his comrade Ulrich I of Württemberg (1265). After Ulrich's death, as the guardian of his underage sons Ulrich II and Eberhard I, he also ruled their county and thus rose to become the most influential count in Swabia. His policy of expansion in the lowlands , which he presumably headed as the Lower Swabian governor, he made enemies of several counts who were wealthy here, as it soon turned out to be.

Decline after the interregnum

The Swabian Count Rudolf von Habsburg , elected king in 1273 , had set himself the goal of returning royal property that had been lost in the Interregnum , including the castle and town of Grüningen, back into the hands of the Empire. He also wanted to win the vacant ducal dignity for his own house. He entrusted his brother-in-law Albrecht II von Hohenberg , whom he appointed as Reichslandvogt for Lower Swabia , with the implementation of this revindication strategy . This was supported by the Counts of Tübingen and Asperg and probably decisively by the Margrave of Baden , from whom Hartmann had taken some positions between Stuttgart and Heilbronn.

While Hartmann II was more willing to compromise on the imperial estate annexed by Ulrich I, he strictly refused to surrender the town of Grüningen, which he had expanded. So that he and his son Hartmann III. A seven-year conflict with the Hohenberg Count and his growing circle of supporters set in, which ultimately sealed the decline of their house.

Death and Succession

Hartmann II presumably died after his testamentary foundation on the Marien Altar of the Grüninger Bartholomäus Church , which the Speyr bishop Friedrich von Bolanden confirmed in 1277. The count may have died in combat or succumbed to any wounds that he may have sustained in the violent clashes with the royal armed forces . However, they could also have taken advantage of his death when they took Grüningen around 1275 and set the new church on fire. For this time of death speaks that in 1275 no senior is named and apparently an inheritance and name division had taken place. Because while in the Unterland only "Hartmann von Grüningen" will appear in the future, in the Oberland only the sons Konrad and Eberhard will be the "Counts of Landau".

Defeat and decline

In the also controversial city of Brackenheim , the first-born son Hartmann III. On October 19, 1277, repel the enemy troops despite their superior strength and lead numerous prisoners to Grüningen. According to an old hymn book, this victory was celebrated as the revenge of the church saint Bartholomew for the desecration of the church in 1275. In 1280, however, he had to face a far larger army and surrender in open battle. He died in the dungeon on Hohenasperg and was buried in his new church. Burgraviate and the city of Grüningen, including the imperial storm flag, fell back to the empire or into the hands of Albrecht II of Hohenberg .

Hartmann's brother Konrad rebelled against the loss of Grüningen in vain for years. He only managed to get compensation for the family's property in the city. After they had finally lost the county of Grüningen, Hartmann's brothers renounced this title, named themselves only after their castle Landau and no longer gave the first name Hartmann, which is traditionally associated with the Reichssturmfahnlehen.

family

For a first marriage of Hartmann II, according to tradition, with a Franconian mistress von Schlüsselberg , no evidence has yet been found. The early marriage of his daughter Agnes (before 1263) and the distinction between senior and junior ( Hartmann III. ), Which was first made in 1265, seem to point to a first marriage, which, according to Heyd, is also confirmed by tradition that Hartmann II Bartholomäuskirche was buried next to his wife. Since Hedwig survived him for a long time, only a first wife, the mother of his successor Hartmann III, can be meant.

The marriage with his cousin Hedwig von Veringen , however, is definitely documented. Because of their fourth degree kinship (common grandparents) they needed papal dispensation for their marriage in 1252 , which Pope Innocent IV granted in Perugia on October 2nd, 1252, in order to eliminate the harmful conflict between the two related houses. It is possible that she brought Landau Castle, which was never mentioned before with Count von Grüningen and which later gave its name , to the marriage.

Due to the need marriage dispensation must be either the unknown mother Hartmanns a Veringer count's daughter have been and sister of Hedwig's father or sister of Hartmann's father was married to a Count of Veringen. Conrad I von Grüningen and Hermann von Württemberg are partly adopted as the father. Because of his Nellenburg-Veringian guiding name and the shared legacy of Ulrich and Hartmann II in Veringen, however, as Heyd also notes, Count Eberhard von Württemberg seems more obvious. This is mentioned in various sources from 1231 to at least 1236.

Hartmann's II descendants include:

- Agnes von Grüningen, who was married to Count Rudolf II of Montfort before 1263 and must therefore come from her first marriage;

- Hartmann III. von Grüningen (* before 1252, 1265 legally competent, † 1280), who probably comes from his first marriage and in 1275 had the Lower Swabian legacy with the county of Grüningen;

- According to Sommer, Anna von Grüningen-Landau became prioress of Offenhausen Monastery “after the death of her father” and documented her as such in 1277, which is why she must have come from her first marriage;

- Adelheid von Grüningen, abbess of Heiligkreuztal , who, according to Mereb, should also come from a first marriage;

- Konrad II von Grüningen-Landau († 1300), documented as the son of Hedwig, from 1275 autonomous "Count of Landau", from the death of his half-brother Hartmann III. in October 1280 as "Graf von Grüningen" head of the entire house, had to give up the claims to the county of Grüningen and accept a serious political loss of importance for his family, which is why he finally called himself only Graf von Landau ;

- Ludwig von Grüningen-Landau († after 1300), documented as the son of Hedwig, was "Major Canonicus" in the cathedral chapter of Augsburg , Kirchherr zu Grüningen and Cannstatt ;

- Eberhard I. von Grüningen-Landau († 1322), documented as Hedwig's son, from 1275 "Count von Landau", who tried in vain to strengthen the position of the house in the lowlands by marrying Richenza von Calw-Löwenstein .

- Adelheid von Landau, married in 1293 to the noble Berthold von Mühlhausen , who documented several times in Grüningen and worked closely with Count Eberhard I of Württemberg and Konrad von Grüningen-Landau;

Additional information

swell

- Boehmers Regesta Imperii (Online Database) - RI Online

- Peter Fendrich: Regesten of the Counts of Grüningen. (Database), Markgröningen 2013.

- Württembergisches Urkundenbuch (online database) - WUB online

literature

- Gottlob Egelhaaf : The battle near Frankfurt on August 5, 1246. In: Württemberg quarterly books for regional history. Ser. NF, Vol. 31 (1922/24), pp. 45-53.

- Peter Fendrich: Return of the Counts of Grüningen - Insight into the revised history of the county on Heyd's footsteps . In: Through the city glasses - historical research, stories and preservation of monuments in Markgröningen , Volume 10, ed. v. AGD Markgröningen, Markgröningen 2016, pp. 40–47, ISBN 978-3000539077

- Ludwig Friedrich Heyd : History of the Counts of Gröningen. 106 pp., Stuttgart 1829.

- Ludwig Friedrich Heyd: History of the former Oberamts-Stadt Markgröningen with special regard to the general history of Württemberg, mostly based on unpublished sources. Stuttgart 1829, 268 p., Facsimile edition for the Heyd anniversary, Markgröningen 1992.

- Sönke Lorenz , Dieter Mertens and Volker Press (eds.): The house of Württemberg. A biographical lexicon. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart et al. 1997, ISBN 3-17-013605-4 .

- Sönke Lorenz: From Baden to Württemberg. Marbach - an object in the stately interplay of forces at the end of the 13th century. In: Journal for Württemberg State History, 72nd year, Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2013.

- Sönke Lorenz: Count Ulrich von Württemberg, the Battle of Frankfurt (1246) and the rise of the Counts of Württemberg. In: Konrad IV. (1228–1254), Germany's last Staufer King (2012), pp. 71–85.

- Johann Daniel Georg von Memminger : The counts of Grüningen-Landau. Their name and their relationship with the house of Württemberg. In: Württ. Yearbooks for patriotic history, geography, statistics and topography, 1826, issue 1, pp. 69–97 ( Google ) and issue 2, pp. 376–440 ( Google ).

- Ursula Mereb: Studies on the history of ownership of the Counts and Lords of Grüningen-Landau from approx. 1250 to approx. 1500. 108 p., Tübingen 1970.

- Karl Pfaff : The origin and the earliest history of the Wirtenberg Princely House. Critically examined and presented. With seven supplements, three family tables and a historical-geographical map. 111 p., Stuttgart 1836.

- Hermann Römer : Markgröningen in the context of regional history I. Prehistory and the Middle Ages. 291 p., Markgröningen 1933.

- Ingrid Karin Sommer: The Chronicle of the Stuttgart Councilor Sebastian Küng. (Publication of the Stuttgart City Archives, Vol. 24), Stuttgart 1971.

- Karl Weller : King Conrad IV and the Swabians. In: Württ. Vierteljahreshefte 6 (1897), pp. 113–160.

Remarks

- ↑ This picture by an unknown painter from around 1800 still shows the proportions of the city that was expanded in the 13th century and later stagnated.

- ↑ The expansion of the two cities followed the same basic pattern as the old city maps show. And both counts initiated a large sacred building: the Bartholomäuskirche in Grüningen and the collegiate church in Stuttgart.

- ↑ The derivation of the title from a village of the same name near Riedlingen can be refuted. See below and section "Devaluation by historians" in the town history of Grüningen .

- ↑ On September 15, 1228, Count Konrad von Grüningen donated his court Marbach in the parish of Ertingen, in the diocese of Constance, to the hospital of St. Mary the Germans in Jerusalem. Only for the benefit of his "ancestors", which could mean that he had no offspring and that his father Konrad, mentioned in 1227, son of Hartmann I von Württemberg, had already died. See WUB online

- ↑ After the loss of the imperial fief, Konrad II von Grüningen sold the in-house Grüninger "Dominium" to the king. See Ludwig Friedrich Heyd: History of the former Oberamts-Stadt Markgröningen with special regard to the general history of Württemberg, mostly based on unpublished sources. Stuttgart 1829, 268 p., Facsimile edition for the Heyd anniversary, Markgröningen 1992, p. 8f.

- ↑ According to Martin Crusius at Ludwig Friedrich Heyd : History of the former Oberamts-Stadt Markgröningen with special regard to the general history of Württemberg, mostly based on unpublished sources. Stuttgart 1829, p. 9): "Anitzo, the city pastor lives in the castle where the old counts once resided" (stone house is a medieval name for city palace).

- ↑ "Count Hartmann von Grüningen the Elder, after he sold Altshausen with the church patronage there to the treasurer Heinrich von Biegenburg, for an exchange with the buyer with regard to the right to certain self-owned people in Altshausen and Veringen." See Karl Pfaff: Der Origin and the earliest history of the Wirtenberg Princely House: Critically examined and presented. With seven supplements, three family tables and a historical-geographical map . 111 p., Stuttgart 1836, p. 70, and Württ. Urkundenbuch. Volume IV., No. 1079, pp. 140-141 + No. 1080, pp. 141-142 WUB online

- ↑ See Böhmer: Regesta Imperii. 5.1. P. 586, and Württ. Document book. Volume IV., No. 1004, p. 54. WUB online

- ↑ On February 2nd, 1241 Ulrich and Eberhard donated a farm in Langenenslingen to the Heiligkreuztal monastery . See Württ. Document book. Volume IV., No. 965, pp. 11-12 WUB online . On July 17th, Eberhard and Ulrich confirmed a purchase from the same monastery WUB online

- ↑ Name changes were not uncommon back then, with the surname anyway, but also with the first name. The father of Ulrich and Eberhard alias Hartmann was probably an Eberhard von Württemberg attested in the thirties (see Ludwig Friedrich Heyd: Geschichte der Grafen von Gröningen. 106 p., Stuttgart 1829, p. 44). While Ulrich and Hartmann were given exclusive names for the two lines in the future, the Nellenburg-Veringian name Eberhard continued to be used by both lines. The name Hartmann expired after the loss of Grüningen.

- ↑ Heyd: Count. 1829, saw Ulrich and Hartmann II as brothers. In addition, acting in a fraternal duet with the Counts of Württemberg went back several generations: 1. Ludwig and Emicho, 2. Hartmann and Ludwig, 3. Konrad and Hartmann, 4. Ulrich and Hartmann

- ↑ In 1246, however, a hitherto unknown Heinrich von Württemberg becomes Bishop of Eichstätt , with whom a "Hermann von Grüningen" (= Hartmann I retired?) Moves in as canon. See Franz Heidingsfelder : The Regests of the Bishops of Eichstätt (until ... 1324) . Erlangen 1938, p. 237f.

- ↑ Also called the Battle of Frankfurt . See also RI V, 1,2 n. 4510b online

- ↑ Konrad usually recorded documents in Upper Swabia. For example in Augsburg WUB online

- ↑ His relationship to Hartmann and Ulrich is unclear.

- ↑ Its origin is unclear, but because of the temporal context and its name, it may have been a relative. Especially since "Hermann" was sometimes written instead of "Hartmann".

- ↑ See Franz Heidingsfelder : The Regests of the Bishops of Eichstätt (until ... 1324) . Erlangen 1938, p. 237f.

- ↑ 1247 Hartmann campaigns for the Oberstenfeld monastery . See WUB online . In 1248 Hartmann and Ulrich stood up for the Strasbourg cleric Engelbert. See WUB online . The Pope praises the Abbot [Konrad] von Reichenau because he was Hartmann u. a. supported in the fight against King Konrad. See WUB online

- ↑ See Böhmer: Regesta Imperii . 5,2, p. 959 or Ludwig Friedrich Heyd: History of the Counts of Gröningen. 106 p., Stuttgart 1829, p. 78f.

- ↑ For example, when he and Ulrich campaigned for a niece in Lyon in 1249: “... H. v. Gruningin comites propter fidem puram et devotionem sinceram, quam ad ecclesiam Romanam gerere dinoscuntur, ... “ WUB online This document thus provides further evidence that this cannot be, as is often assumed, Hartmann I, the 1243 provable was in the service of Frederick II .

- ↑ See confirmation of foundation on WUB online In addition, on this occasion, the undated foundation of the Marienglocke by Hartmann III. from Grüningen .

- ↑ Tradition knows, however, of a Hartmann von Grüningen, who is said to have been buried in the Heiligkreuztal monastery as early as 1273 . See also David Wolleber: Descendant tables for the history of the House of Württemberg , Schorndorf 1591; UB Tübingen Mh6-2 A document dated April 23, 1274 speaks against this year of death, in which a Hartmann “senior” appears for the last time at Landau Castle. See WUB, Volume VII, No. 2417, p. 306 WUB online

- ^ Ludwig Friedrich Heyd: History of the Counts of Gröningen. 106 p., Stuttgart 1829, p. 81.

- ^ Ludwig Friedrich Heyd: History of the Counts of Gröningen. 106 pp., Stuttgart 1829, p. 7.

- ↑ After Ulrich's line acquired Grüningen as an inheritance in 1336, they carried the sub-title Graf von Grüningen into the 19th century. This also refutes Memminger's widespread thesis ( The Counts of Grüningen-Landau. Their naming and their relationship with the House of Württemberg. In: Württ. Yearbooks for patriotic history, geography, statistics and topography, 1826, issue 1, pp. 69–97 ( Digitized version) and issue 2, pp. 376–440 digitized version ) that the Counts of Grüningen had named themselves after a village of the same name near Riedlingen. See also section "Devaluation by historians" in the town history of Grüningen .

- ^ Ludwig Friedrich Heyd: History of the Counts of Gröningen. 106 pp., Stuttgart 1829, pp. 87f.

- ↑ Marriage dispensation due to 4th degree relationship between “Dilect. Fil. No. Vi. Comes Harcimannus de Grueningen et Hedewigis nata comitis de Veringen “See Ursula Mereb: Studies on the history of ownership of the Counts and Lords of Grüningen-Landau from approx. 1250 to approx. 1500. 108 S., Tübingen 1970, p. 13, and Regesta Imperii V , 2.3 n.8530 RI Online .

- ↑ However, Ulrich seems to have had a Dillinger Count's daughter as a grandmother or mother, as he was able to assert inheritance claims when they died out.

- ↑ According to Georg Rüxner's less credible tournament book, however, this Eberhard is said to have been married to a daughter of Duke Berthold V von Zähringen. See Ingrid Karin Sommer: The Chronicle of the Stuttgart Councilor Sebastian Küng. (Publication of the archive of the city of Stuttgart, vol. 24), Stuttgart 1971, p. 49 u. 174. More likely would be a Zähringer granddaughter and daughter of Berthold or Egino von Urach. Nothing is known of another marriage of this Eberhard, who was not included in the Württemberg counts.

- ↑ See Ludwig Friedrich Heyd: History of the Counts of Gröningen. 106 S., Stuttgart 1829, p. 39, Karl Pfaff: The origin and the earliest history of the Wirtenberg princely house: critically examined and presented. With seven supplements, three family tables and a historical-geographical map . 111 S., Stuttgart 1836, p. 31, and Ingrid Karin Sommer: The Chronicle of the Stuttgart Councilor Sebastian Küng. (Publication of the archive of the city of Stuttgart, vol. 24), Stuttgart 1971, p. 49 u. 174.

- ↑ WUB Volume VI., No. 1833, pp. 228-229 WUB online

- ↑ The daughter Elisabeth von Rudolf and Agnes was married to Truchsess Eberhard von Waldburg in 1275. See WUB Volume VII, No. 2520, pages 381-382 WUB online

- ↑ Ingrid Karin Sommer: The Chronicle of the Stuttgart Councilor Sebastian Küng. (Publication of the archive of the city of Stuttgart, vol. 24), Stuttgart 1971, p. 171 (source: Pfeilsticker).

- ↑ WUB Volume VIII, No. 2652, p. 10, WUB online

- ^ Sönke Lorenz, Dieter Mertens and Volker Press (eds.): Das Haus Württemberg. A biographical lexicon. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart et al. 1997, ISBN 3-17-013605-4 , p. 52.

- ↑ WUB Volume XI., No. 5219, pp. 201-202 WUB online

- ↑ WUB Volume IX., No. 3885, pp. 296-297 WUB online

- ↑ Berthold von Mühlhausen (near Stuttgart) sold on July 15, 1293 with the consent of his wife Adelheid, Countess von Landau , to the Bebenhausen monastery a farm she had brought in in Zuffenhausen . See WUB Volume X, No. 4402, pp. 156-157, WUB online

See also

- City history of Grüningen ( Markgröningen ) and Reichsburg Grüningen

- Count Ulrich I of Württemberg

- Root list of the House of Württemberg (for Counts of Grüningen inaccurate)

Web links

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hartmann II of Grüningen |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Count of Grüningen |

| DATE OF BIRTH | before 1225 |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1275 |