livestock farming

Animal husbandry describes the self-responsible care of humans for an animal over which they have actual or legal power of disposal . The key aspects of animal husbandry are the feeding , care and accommodation of the animal. A distinction is essentially made between the keeping of farm animals , pets and wild animals .

Categories

A distinction is primarily made between three categories - farm, domestic and wild animal husbandry. While wild animals are never domesticated , farm animals are mostly domestic animals. Pets can be domesticated.

Farm animal husbandry

The livestock attitude is the attitude of animals (mostly domestic animals ) for economic reasons (food supply, source of raw materials, transportation and means of transportation).

A special characteristic is the breeding of regional breeds or breeds adapted to the demand development and their further development over time:

- the keeping of working and pack animals (horse, donkey, camel, llama, elephant, etc.)

- in the broader sense also of guard animals (dog) and animals used in pest and vermin control (cats, mongoose etc.) as well as hunting companions (e.g. hunting dog , hunting )

- The keeping of livestock for animal production includes:

- the pig production is the most important segment of the meat supply of the non-Islamic societies. The selection of pig breeds and husbandry methods follow the development of demand in the meat sector.

- the production of cattle to produce milk, meat, and to a limited extent traction. The common cattle breeds differ considerably in terms of their performance characteristics.

- the horses in Asia is also notably changed for milk and meat production, in Europe the train and mount for recreational companion. The different horse breeds meet the most diverse requirements.

- the sheep attitude, for the production of meat, wool and milk can boast racial and national differences.

- the poultry production is used for production of eggs and poultry meat. A distinction is made between cage, floor and free-range housing . The diverse breeds of chicken are maintained and further developed by poultry breeding associations.

- the rabbit production ,

- as well as the keeping of numerous other farm animals, such as goats , house donkeys , camels and New World camels (lama and others), reindeer , and many others.

- The apiculture (beekeeping and posture)

- the keeping of farm animals for the production of animal products

- keeping for medical research by means of animal experiments ( laboratory animals such as the domesticated laboratory mouse )

One differentiates between livestock farming

- the extensive livestock farming from the intensive livestock farming , the latter agricultural historically only been relatively recently in the developed countries has become more important.

- the conventional animal husbandry of the organic livestock production .

Pet ownership

The pet attitude is the attitude of animals of any kind, so wild, commercial as well as domestic animals , in private households. Pets can be domesticated farm animals or pets as well as non-domesticated wild animals.

Wildlife husbandry

The Wildlife attitude the attitude is wild, non-domesticated animals of different of a variety and in the history of ever-changing reasons (meat production, prestige , entertainment, hobby , hunting , science , education , nature and species protection ):

- Agricultural game keeping

- Aquafarming (there are no "house oysters", "house shrimp" or "house salmon")

- Zoo animal husbandry ( zoos , menageries , marine theme parks and dolphinariums )

- Aquaristics ( aquariums , vivariums )

The keeping of deer (especially red deer, fallow deer and roe deer) for the production of game meat is still counted as keeping wild animals - this is where the boundaries to farmed animal keeping begin to merge; Even deer are now domesticated for breeding purposes. The same applies to fur animals.

The keeping of animals for the production of medical and pharmaceutical preparations is also at the limit: Keeping snakes for the production of antidotes or monkeys for medical research is still part of the keeping of wild animals, other animals are more or less domesticated or on the way to domestication.

Legal provisions

The legal provisions on animal husbandry can be roughly divided into norms that regulate the relationship between private individuals (civil law) and norms in which the state dictates something to the citizen in relation to superiority and subordination (public law). In civil law, in particular tort law plays an important role, but other areas such as the tenancy can be important. In public law there are regulations on keeping animals, particularly in hazard prevention law, but also in nature conservation and species protection law.

Liability law (Germany)

So-called animal owner liability applies to animal husbandry in Germany .

According to this, the pet owner can be held liable for the damage caused by his animal. This concerns the civil law responsibility for economic damage in the law of obligations , more precisely in the law of tort or liability law (as opposed to the public law responsibility in hazard prevention law). It is regulated in Section 833 of the German Civil Code (BGB).

Damage caused by small pets is covered by private liability insurance, for dogs and horses there is animal owner liability insurance, which is even required for dogs in some federal state laws.

The term pet owner

The animal owner liability is linked to the term animal owner . The owner of the animal is the person who normally has control over the animal (power of determination), who pays for the costs (maintenance) of the animal in his own interest, who generally benefits from the animal's advantages (value and benefit) and who takes on the economic risk of loss of the animal (risk of loss).

The term pet owner is not to be equated with the term owner . In practice, however, the holder is usually the owner or someone who acts like an owner. A common difference to ownership (in the sense of the BGB) could be seen in the durability of the relationship between the pet owner and the animal: Anyone who borrows a dog to go for a walk becomes the owner, but not the pet owner.

Strict liability (§ 833 S. 1 BGB)

In principle, an animal owner is liable for damage caused by his animal. This is the case, for example, when a horse kicks or bites or when a dog jumps or bites a third party. The reason for this no-fault liability is the risk inherent in unpredictable animal behavior ( specific animal risk ).

On the other hand, there is no case of animal owner liability if an animal is under the direction of a person and obeys the will of that person. This would be the case, for example, if a rider (not the owner) deliberately overrides a third party or someone orders the owner's dog to bite a third party (chased dog).

Liability according to § 833 sentence 1 BGB occurs as so-called " strict liability " even if the owner is not at fault. Only if

- "The damage is caused by a pet that is intended to serve the occupation, employment or maintenance of the animal owner" ( § 833 sentence 2 BGB),

the holder has the opportunity to provide evidence of exoneration. In this case, liability does not apply if the owner of the tame farm animal can prove that he has taken the necessary care or the damage could not have been averted even with the necessary care. This proof of exoneration is not open to owners of so-called luxury animals or wild animals , they are always liable regardless of fault.

Public law (especially hazard prevention law)

Which animals may be kept at all depends primarily on whether these animals represent a danger in concrete or abstract terms. Therefore, this is primarily determined by the law to avert danger, also called police law (part of public law). In Germany, hazard prevention law is almost always a matter for the federal states.

General regulations on keeping animals can be found in animal welfare law . The keeping of wild animals can also be restricted by regulations on species protection . For many species, for example, legal keeping is required through a certificate according to the Washington Convention on the Protection of Species , implemented in EU law by Regulation (EC) No. 338/97 (usually called "CITES certificate" after the English abbreviation).

State law (Germany)

The federal states in particular decide which species can be kept as pets . Hessen was the first state to introduce a ban on the keeping of wild animals as part of the amendment to the Hessian law on public safety and order in October 2007 . Under this law down next several Scorpio - and poisonous spider species especially reptiles such as crocodiles and some Twisting and numerous venomous snake species . The regulation only applies to keeping for private and non-commercial purposes. Thus zoos do not fall under this regulation. For animals that were already in private ownership when the change in law came into force, grandfathering applies with notification requirements.

Federal law (Germany) and European law

For several years there have been legal provisions in the European Union (EU) and Germany that regulate a large number (but not all) of forms of wild animal husbandry. The purpose of these regulations is not only to protect people from animals, but also, in particular, to protect individual animals or species from humans (animal protection law and nature and species protection law). The EU directive on the keeping of wild animals in zoos has existed since 1999 . In Germany, since March 2002, Section 51 of the Law on the New Regulation of Nature Conservation and Landscape Management and the Adaptation of Other Legal Provisions (BNatSchGNeuregG) and the individual nature conservation laws of the federal states has regulated all matters relating to the keeping of animals in zoological gardens. While zoos were previously practically facilities without a statutory supervisory authority, since then they have to surrender individual animal species in the event of violations or can even be closed.

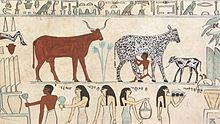

History of animal husbandry

To research the early history of animal husbandry, before the existence of written sources , there are two sources: Genetic data on domesticated species and their wild relatives (and for a few years now by evaluating aDNA from subfossil remains such as bones) and the results of archaeological excavations Modern encounters with people from hunter-gatherer cultures seem likely that they may have occasionally caught, tamed and kept wild animals (such as parrots) as pets in the past , but this is not recognizable from the findings and will probably never be demonstrable. The only animal species whose regular husbandry (and domestication) can be proven before the Neolithic Revolution is the domesticated dog . All other forms of animal husbandry probably go back to the Neolithic. The data on whether animal husbandry preceded arable farming or vice versa is contradictory; as far as can be reconstructed, both cultural techniques began parallel to one another. Although the keeping of different animal species began at different times and in different regions, the data have emerged according to three regions of origin of particular importance: the “ fertile crescent ” in the Middle East, northern China and the Andes of South America. As far as can be reconstructed, a sedentary way of life with permanent settlement of villages preceded the invention of agriculture, so it was not its consequence. In the well-explored Middle East, it can be shown that at the time of the beginning of agriculture, the frequency of the most popular types of prey fell sharply. In research, therefore, a model is often favored that, based on large, organized driven hunts, led to some captured animals being left alive in order to expand the stock, which were kept gradually longer and finally all year round . (Such organized driven hunts have been archaeologically proven by kilometer-long dry stone wall campaigns, probably to catch migratory gazelles such as the Dorkas gazelle .) The keeping would therefore have preceded the domestication, which would initially have been more or less unintentional (for the chronological sequence see also under domestication ). In addition, some animal species (the wolf, but possibly also the wild boar) would have sought closeness to humans because they found more food in their settlement areas, so they would have domesticated themselves more or less by themselves in interaction with humans.

All early domestic animal species were in genetic contact with the wild animals of their ancestral species for centuries to millennia, conscious breeding may have started much later, so it followed animal husbandry, sometimes for centuries. It was only once pets were known that humans would finally have come up with the idea of consciously trying to take other animal species into their care.

The Neolithic cultural techniques of agriculture and animal husbandry, proceeding from the areas of origin, made their way to almost all other landscapes on earth. Based on the genetic data, it turned out that their spread was more due to the migration of groups of people who brought their animals with them. If wild relatives lived in the new habitat, their genes contributed to the domestic animal species' gene pool through occasional crossing via introgression . In addition, there has also been a spread through imitation ( cultural transfer , cultural diffusion). Some cultures later gave up agriculture entirely in favor of animal husbandry, these pastoral peoples then sometimes developed into secondary nomads .

Only cultures that had developed a division of labor and possessed a complex hierarchy of rulership were able to raise the material and human resources to keep animals only. The animals only remain in human care under certain safety conditions. The keeping of wild animals served in most cases to represent power and wealth. In the case of some animal species, such as the cheetah , which is now threatened with extinction , this has led to a massive reduction in the total number of animals.

It was only with the establishment of scientific disciplines in the 18th and, above all, the 19th century, that the reasons and goals of wildlife husbandry changed. The founders of the first zoological gardens appeared with the aim of founding scientific institutions. The name “Zoological Garden”, which was first used in London in 1828 , refers to this scientific claim. The tasks of the zoos have steadily evolved over the course of history. Today's scientifically managed zoos define their tasks as nature conservation (species protection), education, research and recreation .

Animal husbandry in criticism

The various forms of animal husbandry were and are constantly being criticized. So today there is a broad spectrum from compromise to militant opponents of certain forms of animal husbandry - animal rights activists , animal rights activists and animal liberators , but also people who keep animals themselves and want to improve their conditions. Both those responsible for factory farming and those responsible for the zoological gardens have dealt with the criticism. In Great Britain, criticism from animal rights activists has led to the closure of all dolphinariums . In 2004 the Belgian government banned the keeping of wild animals in the circus . On the other hand, pet keeping is largely undisputed in the public discourse, although here too certain keeping conditions can give rise to criticism.

In connection with the criticism of animal husbandry, the terms "species-appropriate" or "species-appropriate" are often used, which are mutually identical. The term “ species-appropriate husbandry ” is relative, as it has to be redefined for each animal species and is therefore not sufficient as a categorization of a certain type of husbandry. In addition, due to new findings in behavioral biology and insights from animal owners, the term is constantly being redefined in relation to a certain species of animal, despite fixed criteria.

The use of antibiotics in animal husbandry is also controversial . Resistant pathogens can develop through these active substances, which can be transmitted to humans and cause severe, sometimes untreatable infections . This is why the European Medicines Agency restricted the use of reserve antibiotics in animal husbandry in July 2013, for example . Colistin , for example, should only continue to be used to treat sick animals and not to prevent diseases. Tigecycline , from the glycylcycline class , should therefore not be used in animal husbandry. On the other hand, it would be a violation of the Animal Welfare Act not to treat sick animals according to the state of the art.

Animal rights activists sometimes refer to keeping wild animals as captivity .

Web links

- Link catalog on animal husbandry at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Livestock husbandry - Information from the Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jürgen Unshelm: Environmentally and animal-friendly keeping of farm, pet and companion animals . Georg Thieme Verlag, 2002, ISBN 9783826331398 , p. 34 ff.

- ↑ Heinz Thomas in Palandt , Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, 62nd edition, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49837-X § 833 paragraph 9 (with reference to the Federal Court of Justice : BGH, NJW-RR 1988, 655)

- ↑ a b OLG Zweibrücken, notification decision of August 12, 2004, file number 1 U 65/04, under I. 2. a) 2. Paragraph in the decision database of the State of Rhineland-Palatinate ( Memento of August 28, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (HTML, accessed July 1, 2009); Quote: “Animal owner is who has the power to determine the animal and who pays the costs of the animal in his own interest and bears the economic risk of his loss (BGH NJW-RR 1988, 655, 656). The characteristic of the owner property is used to assign the source of danger to the person responsible for the risk, i.e. to the person who uses the animal in their own interest and who decides on its use and existence.Therefore, the owner property usually lies with the owner or the person who behaves like an owner ( Lorenz, strict liability of the pet owner, p. 328). "

- ↑ a b c d Heinz Thomas in Palandt , Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, 62nd edition, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49837-X § 833 paragraph 6

- ↑ Heinz Thomas in Palandt , Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, 62nd edition, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49837-X § 833, paragraph 6 (with reference to the Federal Court of Justice : BGHZ Volume 67, p. 129)

- ↑ Heinz Thomas in Palandt , Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, 62nd Edition, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49837-X § 833 Paragraph 6 (with reference to the Federal Court of Justice : NJW 1952, p. 1329 and Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf , NJW-RR 1986, P. 325)

- ^ Heinz Thomas in Palandt , Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, 62nd edition, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49837-X § 833, paragraph 1

- ↑ Geigel, The Liability Process , 25th edition, Munich 2008, Verlag CH Beck, ISBN 978-3-406-56392-8 , Chapter 18: Liability of the animal owner (§ 833 BGB) and the animal supervisor (§ 834 BGB).

- ↑ Hesse prohibits keeping dangerous wild animals ( memento from November 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) - press release of the Darmstadt Regional Council of October 19, 2007

- ↑ an overview in: Melinda A. Zeder, Daniel G. Bradley, Eve Emshwiller, Bruce D. Smith (editors): Documenting Domestication. new genetic and archeological paradigms. University of California Press, Berkeley, etc., 2006. ISBN 978-0-520-24638-6 .

- ↑ Melinda A. Zeder: Archaeological Approaches to Documenting Animal Domestication. In: Melinda A. Zeder, Daniel G. Bradley, Eve Emshwiller, Bruce D. Smith (editors): Documenting Domestication. new genetic and archeological paradigms. University of California Press, Berkeley, etc., 2006. ISBN 978-0-520-24638-6 .

- ↑ Melinda A. Zeder, Guy Bar-Oz, Scott J. Rufolo, Frank Hole (2013): New perspectives on the use of kites in mass-kills of Levantine gazelle: A view from northeastern Syria. Quaternary International 297: 110-125. doi: 10.1016 / j.quaint.2012.12.045

- ^ A b Greger Larson & Dorian Q. Fuller (2014): The Evolution of Animal Domestication. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 45: 115-136. doi: 10.1146 / annurev-ecolsys-110512-135813

- ↑ Antimicrobial resistance - European Medicines Agency provides advice on use of colistin and tigecycline in animals. EMA press release of July 30, 2013

- ↑ peta.de : Keeping in captivity in the zoo ( memento from February 19, 2012 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on January 4, 2012