John Vanbrugh

Sir John Vanbrugh [ vænbrə ], and [ vənbruː ] (baptized January 24. 1664 in London , † 26. March 1726 ) was an English Baroque - architect and dramatist . Its most famous building is Blenheim Palace . His two provocative comedy The Relapse ( Relapse , 1696) and The Provoked Wife ( The provoked Wife , 1697) were big stage successes and were controversial.

Life

Vanbrugh held radical views all his life. As a young man he was a staunch supporter of the Whig Party and involved in the Glorious Revolution , which sealed the victory of parliamentarism in England. In its course, the absolutist-minded King James II was replaced by Wilhelm von Oranien-Nassau , who in 1689 as William III. ascended the English throne. Vanbrugh's involvement in the coup led to him spending some time as a political prisoner in the Bastille of Paris .

With his sexually blunt plays, in which he defended the rights of married women, he violated the rules of English society in the 18th century. He was therefore repeatedly attacked and was the main target of Jeremy Collier's book, A Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage ( A Brief Contemplation of the Immorality and Godlessness of the English Stage ).

As an architect, he created buildings that were later referred to as the English Baroque . His architectural work was no less bold than his early political activities or his stage plays. With this too he aroused criticism from conservatives.

Vanbrugh's London career cannot be described as straightforward. He tried to reconcile his life as a playwright, theater director and architect and often pursued several activities in parallel.

Early years

Information about Vanbrugh's family background and his early life has come down mostly in the form of rumors and anecdotes . Vanbrugh's biographer Kerry Downes was able to show in his Vanbrugh biography published in 1987 that even the data of reputable sources such as the Encyclopædia Britannica and the Dictionary of National Biography are based on vague assumptions of the 18th and 19th centuries that become too general over the decades recognized facts developed. This article draws on recent research by Downes (1987) and McCormick (1991).

Vanbrugh was born in London in 1664 and grew up in Chester , where the family fled during the Great Plague of 1665/1666. Downes doubts the statements of previous researchers that Vanbrugh came from a family of lower middle class and interprets this as a misinterpretation of information from the 18th century that his father Giles Vanbrugh the profession of a "sugar bakers" (literally confectioner exercised). The confectionery profession implies prosperity, because it was not used to describe the maker of sweets, but the owner of a factory in which cane sugar from Barbados was refined. Sugar processing was usually connected to the sugar trade and was a lucrative line of business. Downes was able to use the example of a Liverpool confectioner to show that he was able to generate a considerable income of around 40,000 pounds a year. This throws a very different light on Vanbrugh's social background than the picture of youth in a Chester candy store, which one of the Vanbrugh biographers of the 19th century, Leigh Hunt, drew in 1840 and which shaped later biographies.

What is unknown is what Vanbrugh did between the ages of 18 and 22 after he left school. There is no evidence to suggest that he studied architecture in France at this time. As Laurence Whistler noted in his Vanbrugh biography of 1938, there was no reason for a talented young man to go to France to study architecture. England would have offered sufficient opportunities for this. Vanbrugh's first designs for Castle Howard from 1700 also show that he was largely unfamiliar with architectural drawings. Had he worked for a French architect for a few years it would have been one of the first things he would have learned.

In 1686 Vanbrugh received an officers commission in the regiment of one of his distant relatives, the Earl of Huntingdon. Allocating such commissions was reserved for the commanding officer of the regiment. That Vanbrugh received such a position is another indication that he had important connections because of his background. Despite these distant aristocratic relatives and the occupation of his father as a confectioner, Vanbrugh never had sufficient equity during any phase of his life to independently finance ventures such as the Haymarket Theater . He resorted to loans and equity investments and was in debt for most of his later life. This may also have been due to the fact that John Vanbrugh had eleven siblings with whom he had to share his father's inheritance.

Political activities and the stay in the Bastille

From 1686 Vanbrugh was actively involved in the plans to overthrow Jacob II by an armed invasion of William of Orange-Nassau . His participation in the later so-called Glorious Revolution expresses his lifelong identification with the main concern of the Whig Party, the preservation of parliamentary rule.

In September 1688, two months before William landed with his troops in England, Vanbrugh, who gave him news of was The Hague had delivered, the French arrested Calais. He was accused of espionage and spent the next four and a half years in French prisons, including the Bastille in Paris, before being exchanged for a French political prisoner. The experience of imprisonment, which he entered into at the age of 24 and from which he was released at 29, seems to have triggered a clear rejection of the political system and a predilection for the comic playwrights and architecture of France. The assumption that Vanbrugh wrote parts of his comedy The Provoked Wife while imprisoned in the Bastille is doubted by modern scholars.

After his release from the Bastille in 1692, Vanbrugh was forced to stay in Paris for another three months. These three months gave him the opportunity to see architecture that had no counterpart in England. Vanbrugh returned to England in 1693 and took part in the 1694 naval battle against the French in Camaret Bay. The exact time at which he retired from military service to live in London in the mid-1690s is unknown.

The "Kit Cat Club"

Vanbrugh belonged to the Whig Party and was a member of the Kit Cat Club belonging to this party . Because of his charming personality and his ability to make friends - quirks of character attributed to him by many of his contemporaries - he was one of the most popular and beloved members of this club. Today the club is mostly described as the social meeting place for politically and culturally active Whig members. Its members included many artists and writers such as William Congreve , Joseph Addison , Godfrey Kneller and politicians such as John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough , Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset , Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle-upon -Tyne and Sir Robert Walpole .

Politically, the club pursued the goals of a strong parliament, a restricted monarchy, resistance against France and a Protestant succession on the throne, even if the club outwardly emphasized its role as a social meeting place. The Vanbrugh biographer Downes speculates that the origins of the Kit-Cat Club go back to the times before the political upheaval of 1689 and that it played a role as a secret political alliance in the so-called Glorious Revolution that led to the upheaval. Horace Walpole , son of Kit Cat member and English Prime Minister Robert Walpole, claimed that the respectable senior members, generally described as salon lions, "were in fact the patriots who saved Britain," suggesting the role the club members played in the "Glorious Revolution". Since secret political alliances are usually poorly documented, this speculation cannot be substantiated. If the assumption is correct, however, then Vanbrugh - who spent years in French prisons because of his involvement in this upheaval - not only joined some London salon lions, but also re-established contact with old friends and former co-conspirators.

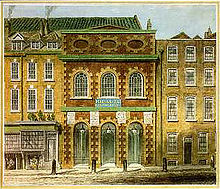

The theater on Haymarket

In 1703 Vanbrugh acquired land and commissioned the construction of a new, self-designed theater on Haymarket in London. The theater opened as the Queen's Theater in 1705.

Vanbrugh's Queen's Theater was to serve as a venue for a group of actors led by Thomas Betterton and give the London theater scene more opportunities to develop. A wide range of entertainment options was available to the London public: opera , animal training , juggling , pantomime , dancing troupes and concerts by famous Italian singers competed for their favor and entrance fees. Vanbrugh acquired the drama company in the hope of making money from the theater. However, the purchase of the actor group also obliged him to pay the actors' salaries and ultimately led to his being in charge of the theater. But he had neither the necessary experience nor enough time for this, especially since from 1705 he supervised the construction of the Blenheim Palace , among other things .

Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that his theater management is described as confused, inefficient, and full of misjudgments ( numerous signs of confusion, inefficiency, missed opportunities, and bad judgments - Judith Milhouse, 1979). Vanbrugh separated from the theater business in 1708 with great financial loss. His contemporaries found it remarkable that during his time as theater director Vanbrugh paid his actors (and as an architect those of his construction workers) not only reliably, but always in full. It was more common in 18th century Britain to be reluctant to meet such financial obligations. Because Vanbrugh himself was the victim of such poor payment practices, he had significant financial problems throughout his life.

The Queen's Theater started a long theatrical tradition on the Haymarket. From 1710 to 1745 almost all of Georg Friedrich Handel's operas and many oratorios were premiered in the building . In 1790 the building, named King's Theater since 1714, was destroyed by fire. Another King's Theater was built on the site of the theater ; Today, here is Her Majesty's Theater from 1897, where musicals are mainly performed. At another point in the Haymarket, theater has been played in changing buildings since 1720, and since 1820 in the Theater Royal Haymarket designed by the architect John Nash, which has also been rebuilt several times .

Marriage and death

In 1719, the 55-year-old Vanbrugh married the 26-year-old Henrietta Maria Yarborough. Despite the considerable age difference, the marriage that resulted in two sons was arguably a happy one. In contrast to the libertines and mockery of his pieces, Vanbrugh's private life was without scandal.

In 1703 he had a modest townhouse built from the ruins of Whitehall Palace, which Jonathan Swift derisively referred to as a "goose pie". However, he spent most of his married life in Blackheath , which was not considered part of London at the time, and lived there in the house he built on Maze Hill in 1717, now known as Vanbrugh Castle . This house with its round tower resembles a Scottish castle and looks like it is fortified. In some ways, Vanbrugh seems to anticipate the romantic neo-Gothic spirit . In 1714 Vanburgh was raised to the nobility by King George I as a Knight Bachelor ("Sir"), in 1726 he died in his London town house.

The playwright

When Vanbrugh came to London in the 1690s, the city had only one royally recognized theater company with a permanent venue. After a long internal dispute between the stingy theater management and the dissatisfied actors, this theater group broke up into the two acting groups United Company and Rebel actors . Actor Colley Cibber seized the opportunity to write a playable comedy for the understaffed United Company called Love's Last Shift, Or, Virtue Rewarded ( The Love's Last Shift, Or Virtue Rewarded ). He wrote the role of the vain, extravagant Sir Novelty Fashion for himself and won the hearts of London audiences.

In Love's Last Shift , female patience is tested by a runaway spouse, and the play ends in a dramatic finale in which the deceitful husband, kneeling in front of his wife, deeply repents. The piece was a huge box-office success at the time, but has not been played since the early 18th century. Vanbrugh believed the play needed a sequel and began to write the sequel himself.

Relapse or virtue endangered

Vanbrugh's witty sequel The Relapse, Or, Virtue in Danger ( The relapse or the risk of virtue ), he of the United Company offered six weeks later, questioned the role that state that time a woman in a marriage. Not only the converted man to marital fidelity, but also his patient wife are sexually tempted, and both respond to it in a more believable and less predictable way than in Cibber's play. The rather flat characters in Love's Last Shift get a lot more psychological depth in Vanbrugh's sequel.

In a funny subplot, the vain and extravagant Sir Novelty Fashion returns, who first acquires a noble title through bribery and now calls himself Lord Foppington (the English word fop means vain, inflated). Vanbrugh also makes more of him than just a laughable, ridiculous marginal figure - he portrays him as ruthless, ruthless and resourceful at the same time.

Vanbrugh's sequel almost went missing. The remainder of the United Company had not only lost the most experienced actors to the Rebel Actors , but also had problems finding enough suitable new actors to bring the play to the stage. As rehearsals dragged on for ten months, some actors dropped out, and by the end of rehearsals the theater company was on the verge of bankruptcy.

From the beginning, however, the play was a great success and saved the theater group from the financial end. Colley Cibber, who was able to build on his success as Sir Novelty Fashion with the role of Lord Foppington, played a major role in the success.

The provoked wife

Vanbrugh's second comedy The Provoked Wife followed shortly thereafter and was performed by the Rebel Actors . The piece is clearly different in tone from The Relapse , which was designed more as a farce, and was tailored to the greater acting experience of the Rebel Actors . Elizabeth Barry , who played the role of the abused wife Lady Brute, was famous for her tragic talent and ability to move audiences to pity and tears. Anne Bracegirdle , who played her niece, was her comedic complement. The role of Sir John Brute, the cruel husband, was played by Thomas Betterton and is considered one of the high points of his remarkable career. The content of the play - a wife trapped in an unhappy marriage, hesitating whether to leave her husband or find a lover - was unusual for a comedy of the Restoration era and received some criticism.

Reaction to the piece

The puritan clergyman Jeremy Collier selected John Vanbrugh's comedies in particular for his work A Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage, published in 1698 , in order to depict the immorality and squalor of the British stages. He criticized these pieces in particular for the lack of poetic justice - immoral acts were not punished, good ones were not rewarded.

Vanbrugh found these allegations laughable and published an ironic comment in which he accused Collier of being more sensitive to the unflattering portrayal of the church class than to true godlessness. However, public opinion increasingly shared Collier's view. The sexually unambiguous comedies of the English Restoration era became increasingly unpopular with the English audience and therefore increasingly replaced by more "moral" pieces. Cibber's piece Love's Last Shift , which ends with a sentimental scene of remorse, was a forerunner of this trend.

Although Vanbrugh continued to work in different ways for the theater, he did not publish any other pieces of his own. As the audience became less and less interested in the comedy in the style of the English restoration, he increasingly concentrated his creative powers on translation work, theater management and architecture.

The architect

There is broad consensus today that Vanbrugh received no formal training as an architect. However, his inexperience was compensated for by a keen eye for perspective and detail, and by his close collaboration with Nicholas Hawksmoor . The former employee of Sir Christopher Wren was Vanbrugh's closest associate on his most ambitious projects - particularly the construction of Castle Howard and Blenheim Palace .

During his nearly thirty year career as an architect, Vanbrugh designed and built countless buildings. Often his work was only remodeling, such as at Kimbolton Castle , in which Vanbrugh largely followed the instructions of his builders. These houses, which are now often referred to as Vanbrugh's work, do not have the architectural style typical of him.

Vanbrugh's preferred architectural style was the Baroque , which had gained acceptance in mainland Europe thanks to Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Louis Le Vau during the 17th century. The first baroque country house in England, Chatsworth House by William Talman , was not built until 1696, three years before the construction of Castle Howard began.

In the competition for the contract for Castle Howard, the inexperienced Vanbrugh, thanks to his connections and charm, managed to outdo the more experienced Talman, who had far fewer social connections. The builder Charles Howard, third Earl of Carlisle, who, like Vanbrugh, was a member of the Kit-cat Club , chose Vanbrugh as architect in 1699, giving him the chance to transform the typical European Baroque with its exuberant formal abundance into a much more restrained, more subtle variant develop what is now referred to as English Baroque. Castle Howard was the first major architectural work of Vanbrugh. The other major works are Blenheim Palace (commissioned in 1704) and Seaton Delaval Hall (construction started in 1718). The construction work on these three major architectural works overlapped.

Vanbrugh's immediate success as an architect can be attributed to his social relationships. Like him, no fewer than five of his clients were members of the Kit-cat club . His appointment as Comptroller of the Royal Works - inspector of royal works - in 1702 he owes his relationship with Charles Howard, the Earl of Carlisle. In 1703 he was also entrusted with monitoring the construction progress at Greenwich Hospital . He was the successor of the important English architect Christopher Wren , Hawksmoor was the executive architect on site. Vanbrugh's small but clearly visible additions to the almost completed building are viewed as a mental continuation of Wren's original plans and intentions. Originally planned as a hospital and home for impoverished retired sailors, it has also become a grand national monument. Both Queen Anne and her government are said to have been enthusiastic about its execution and are thus responsible for its further successes.

Castle Howard

Castle Howard , designed by Vanbrugh, is now often referred to as the first truly Baroque building to emerge in England. It is also considered to be the building whose style most closely resembles the Baroque style of mainland Europe.

Castle Howard was a building unlike any other in England, and the facades and roofs adorned with columns, statues and flowing ornaments made this Baroque building an instant hit. Most of the parts could be obtained from Castle Howard as early as 1709, but the final work continued throughout Vanbrugh's life. Work on the west wing wasn't even completed until after Vanbrugh's death.

The success of Castle Howard ensured that Vanbrugh received a follow-up contract that led to his most famous architectural feat.

Blenheim Palace

John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough , had defeated the army of the French King Louis XIV with his army in the Second Battle of Höchstädt in the small town of Blindheim (pronounced Blenheim) on the Danube . A grand country estate was a gift from a grateful nation to the victor, Marlborough. Work on the palace began in 1705.

Vanbrugh's work is occasionally criticized for being impractical, bombastic, and more extravagant than its clients originally wanted. This reputation is largely due to his work on Blenheim Palace. The choice of Vanbrugh as the architect for this building project was controversial. Sarah Churchill , the spirited Duchess of Marlborough, wanted Christopher Wren to be the architect for Blenheim Palace. However, a decree from the Treasurer of Parliament , Lord Godolphin , designated Vanbrugh as the architect. The fact that the decree did not name either the Queen or the royal household as the client later proved to be a royal loophole as the cost of construction and internal political struggles increased.

The parliament had approved the construction of the palace at state expense, but did not specify the exact construction cost. The inflow of money was changeable from the start. Queen Anne initially paid some of the construction costs, but payment was increasingly reluctant as the gap to the Duchess of Marlborough, her former closest friend, widened. In 1712 there was a final break between the two women; the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough went into exile. All work on Blenheim Palace was suspended. By that time, £ 220,000 had already been spent on construction, and £ 45,000 was still owed to the craftsmen.

One day after the death of the Queen in 1714 returned the couple Marlborough from exile and became the new king with honor at the court George I. added. The now 64-year-old Duke decided to have Blenheim Palace built on at his own expense. Although Vanbrugh was discouraged by the criticism of his construction, he resumed work as an architect. In 1717 the Duke suffered a stroke that left him helpless; the thrifty and very critical of Vanbrugh Duchess was now the client. The Duchess blamed Vanbrugh for the increasing extravagance of the building, ignoring the fact that both her husband and Parliament had approved the plans. It broke; construction continued under the direction of Nicholas Hawksmoor until 1722.

Blenheim was not only intended to be a large country estate, but also to be a national monument. The lively baroque that characterizes Castle Howard would have been unsuitable for a house that was ultimately also a war memorial. The style of the house should symbolize military success and strength. The east gate in the wall surrounding the palace is therefore more reminiscent of a city gate that is easy to defend than the entrance to a luxurious aristocratic country estate. From the outside it can hardly be seen that this gate also served as a water tower for the palace .

Blenheim Palace is the largest non-royal seat of aristocracy in Great Britain and consists of three parts. The middle wing houses the reception and living rooms, while one of the flanking wings houses the stables, the other the kitchen, laundry and storage rooms. There is no comfort in the reception rooms - they should deliberately appear overwhelming and impressive. The main hall, which leads into a large and frescoed drawing room, is 20 meters high. The salon is oriented towards a 41 meter high victory column in the park of the palace. The trees surrounding them symbolize Marlborough's soldiers. The south portal is crowned by a bust of Louis XIV, who was defeated in Blenheim, and looks down on the wealth of the complex from there. It is not clear whether this completion of the south portal was based on a suggestion by Vanbrugh or was an irony of Marlborough, who won in Blenheim.

With Blenheim Palace, Vanbrugh realized a baroque style in which the wall masses are designed boldly and picturesque. The palace is characterized by a varied silhouette, without lapsing into lavish baroque forms.

Seaton Delaval Hall

Vanbrugh's last work, the rather somber Seaton Delaval Hall , is considered by many architecture critics to be his best work. Vanbrugh only uses baroque ornamentation in a very restrained and subtle way. The shadow cast by every protrusion of the wall and every column is precisely planned, and the silhouette of the building is given equal, if not greater importance than the location of the rooms.

Seaton Delaval House was built between 1718 and 1728 for Admiral George Delaval. It is possible that the design of the house was influenced by Palladio's Villa Foscari , which was built around 1555, as both houses are very similar in certain structural elements. Similar to Castle Howard or Blenheim Palace, two wings flank the central part of the building, which contains the reception and living rooms.

Seaton Delaval Hall is one of the few houses that Vanbrugh designed without the assistance of Nicholas Hawksmoor. The sobriety of their joint constructions is often attributed to Hawksmoor's influence; But Saton Delaval's design is extremely sober - some architecture critics have described it as a dark and cyclopean house that is unlike any other building in England or elsewhere ( Lexikon der Weltarchitektur, 1992 ). While Castle Howard could have stood in baroque Dresden or Würzburg , Seaton Delaval is adapted to the harsh landscape of Northumberland .

Seaton Delaval Hall was acquired by the heir, Lord Hastings , in December 2009 following a call for donations by the UK National Trust .

Aftermath

When Vanbrugh died unexpectedly, his papers found an unfinished manuscript for another comedy, A Journey to London . Vanbrugh had told his old friend Colley Cibber that with this play he wanted to question the traditional understanding of roles in a marriage even more critically than with the two comedies he had written as a young man. It tells the journey of a rural family to London who fell victim to the temptations of the city. It is the wife who, to the horror of her husband, succumbs to the seductive charm of the London demimondial world , and Vanbrugh wanted the play to end in a broken marriage. Cibber, now a highly respected poet and theater director, completed the half-finished manuscript and published it in 1728. In Cibber's opinion, the ending that Vanbrugh had planned was unsuitable for a comedy; he therefore ended the play with a scene in which the wife returns to her husband full of remorse.

In the 18th century, the two pieces that Vanbrugh wrote in the 1690s were only played in censored versions. Both pieces, however, remained popular. Colley Cibber played Lord Foppington in The Relapse over and over again during his long and successful stage career . The role of Sir John Brute in The Provoked Wife became a star role first for Thomas Betterton and later for David Garrick . The Relapse is still performed today in the uncensored version.

With the completion of the Castle Howard designed by Vanbrugh, the baroque style prevailed in England. It is difficult to estimate what influence Vanbrugh had on the architects who followed him. Nicholas Hawksmoor, Vanbrugh's friend and long-time collaborator, designed numerous London churches even after Vanbrugh's death. Vanbrugh's cousin and student Edward Lovett Pearce became one of Ireland's greatest architects . Vanbrugh's architectural style has influenced the architecture of countless English country houses; some of those created by Vanbrugh can also be seen. The best preserved country houses include Kimbolton (1707-1709), King's West (1711-1714), the entrance front of Lumley Castle (circa 1722) and the northern part of Grimsthorpe (1723-1724).

Vanbrugh is reminiscent of the names of numerous inns, streets, university buildings and schools in Great Britain.

literature

- Max Dametz: John Vanbrugh's life and works . (= Vienna Contributions to English Philology, ISSN 0083-9914 ; Volume 7). Braumüller, Vienna / Leipzig 1898 (digital copy: Google Books, accessible via US proxy ; reprint: Johnson, New York / London 1964)

- Kerry Downes: Sir John Vanbrugh. A biography . Sidgwick and Jackson, London 1987, ISBN 0-283-99497-5

- Frank McCormick: Sir John Vanbrugh. The playwright as architect . Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park 1991, ISBN 0-271-00723-0

- Laurence Whistler: Sir John Vanbrugh, Architect & Dramatist, 1664-1726 . Cobden-Sanderson, London 1938 (Reprint: Milliwood, New York / Kraus, London 1978, ISBN 0-527-95850-6 )

To the architectural work

- Trewin Cropplestone: World Architecture. An illustrated history from earliest times . Hamlyn, London 1963

- Adalberto Dal Lago: Ville Antiche . Fabbri, Milan 1966

- Bonamy Dobrée: Introduction . In: The Complete Works of Sir John Vanbrugh. Volume 1. Nonesuch Press, London 1927

- David Green: Blenheim Palace . Alden Press, Oxford 1982

- Robert Harling: Historic Houses. Conversations in stately homes . Condé Nast, London 1969, ISBN 0-900303-05-0

- Nikolaus Pevsner, Hugh Honor, John Fleming: Lexicon of World Architecture . Prestel, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-89853-137-6

- David Watkin: English Architecture. A Concise History . Thames and Hudson, London 1979/2001, ISBN 0-500-20338-5

To the dramatic work

- Colley Cibber: An Apology for the Life of Colley Cibber . London 1740 (text-critical new edition, edited by John Maurice Evans: Garland, New York and London 1987, ISBN 0-8240-6013-X )

- Michael Cordner: Playwright versus priest. Profanity and the wit of Restoration comedy. In: Deborah Payne Fisk (Ed.) The Cambridge Companion to English Restoration Theater. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2000, ISBN 0-521-58215-6 , ISBN 0-521-58812-X

- Frank Ernest Halliday: Abn Illustrated Cultural History of England . Thames and Hudson, London 1967

- Robert D. Hume: The Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth Century . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1976, ISBN 0-19-812063-X

- Leigh Hunt (Ed.): The Dramatic Works of Wycherley, Congreve, Vanbrugh and Farquhar . Routledge, London 1840

- Judith Milhous: Thomas Betterton and the Management of Lincoln's Inn Fields 1695-1708 . Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale 1979, ISBN 0-8093-0906-8

Web links

- Literature by and about John Vanbrugh in the catalog of the German National Library

- Vanbrugh, The Provoked Wife . Unfortunately only in a shortened and censored version

- Colley Cibber, Apology , vol. 1 ( Memento from August 29, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- Colley Cibber, Apology , vol. 2 ( Memento from October 16, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- Castle Howard

- Blenheim Palace

- Seaton Delaval Hall

Individual evidence

- ↑ Vanbrugh, Sir John . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . 11th edition. tape 27 : Tonalite - Vesuvius . London 1911, p. 881 (English, full text [ Wikisource ]).

- ^ Thomas Seccombe: Vanbrugh, John . In: Sidney Lee (Ed.): Dictionary of National Biography . Volume 58: Ubaldini - Wakefield. , MacMillan & Co, Smith, Elder & Co., New York City / London 1899, pp. 86 - 94 (English).

- ^ William Arthur Shaw: The Knights of England. Volume 2, Sherratt and Hughes, London 1906, p. 279.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Vanbrugh, John |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English baroque architect and playwright |

| DATE OF BIRTH | baptized January 24, 1664 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | London |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 26, 1726 |

| Place of death | London |