Saiga

| Saiga | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Adult male saiga ( Saiga tatarica ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Saiga tatarica | ||||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1766) |

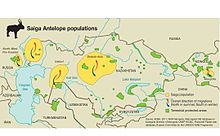

The saiga ( Saiga tatarica ), sometimes also saiga antelope , is a species of ungulate widespread in the Eurasian steppes , which is particularly noticeable for its trunk-like nose. A distinction is traditionally made between two subspecies , the western subspecies ( Saiga tatarica tatarica ) and the Mongolian saiga ( Saiga tatarica mongolica ). In some systematics, both are sometimes understood as separate types, but this view is not generally accepted. After the saigas had almost become extinct in the 1920s, the populations of the western subspecies had increased enormously in the meantime and in the 1950s there were again two million animals. Recently, the populations have again shrunk sharply due to hunting and poaching (for example due to certain ideas in traditional Chinese medicine ) (currently around 100,000 animals). Saigas are now again considered endangered and are almost only found in Russia , Kazakhstan and Mongolia . The absence of animals has a major ecological impact on the preservation of the semi-arid steppes and grassland formations . The Mongolian Saiga is only found in western Mongolia. All other occurrences belong to the western saiga subspecies.

features

Appearance

Saigas look like a small, slightly built sheep, the head is comparatively large. The most striking feature of these animals is the nose, which is enlarged like a trunk. The nasal bones are very complex; each nostril is densely covered with hair and mucous glands. According to various theories, this device is supposed to heat and humidify the air we breathe, which could be useful in the case of dust raised by the herds in summer. According to another theory, it should serve to cool the blood in the event of the threat of overheating. It may also be responsible for the saiga's excellent sense of smell. Only the males have horns that are 20 to 55 cm long and are noticeable due to their semi-transparent, light wax-colored coloring. Only the extreme tips of the horns are black. The horns are slightly bent backwards in a lyre shape and have 12 to 20 transverse ridges. The females are polled. Their passage suggests that the saiga can only live in relatively flat terrain. This allows quick and persistent escape on the plain, but proves to be disadvantageous when jumping and climbing.

The Mongolian Saiga is characterized by its smaller body size, weaker horns, smaller nose and other features in the shape of the skull and fur color.

Coat

The saiga has a dense, woolly fur that consists of longer outer hairs and a shorter, soft undercoat. Winter fur is thicker and, at 4 to 7 cm, about twice as long as summer fur, which measures only 1.8 to 3 cm. In addition, a kind of neck mane forms in the cold season. The fur color is yellowish to reddish brown in summer with lighter flanks, the underside is whitish. In winter the fur is whitish-gray on the top and whitish on the underside. Occasionally albinos occur, while black flies are extremely rare.

Body measurements

The saiga has an average head body length of 120 cm (100-140 cm), a shoulder height of 70 cm and a weight of 50 kg. Males reach a shoulder height of 69 to 79 cm and a weight of 32.5 to 52 kg. The females are slightly smaller with 57 to 73 cm shoulder height and 21.4 to 40.9 kg body weight. The tail is quite short with a total length of only 6 to 12 cm and does not have a tassel. The front hooves are 55 to 68 mm long and 42 to 54 mm wide, the rear hooves are about 10% smaller.

Way of life

Habitat and food

Saigas live in open steppe and semi-desert and avoid steep or rocky terrain and dense vegetation. In summer they also penetrate into forest steppes. In contrast to the relief, the height above sea level hardly plays a role; it is found from 0 to 1,600 m above sea level. The critical snow depth that the animals can cope with is 25 to 30 cm. The diet consists primarily of grasses (especially Agropyron , Bromus , Festuca , Stipa and Koeleria ), but also includes herbs, lichens and shrubs. In spring, the saigas can completely cover their water needs from the damp vegetation and do not look for water points, although these are available all over the steppe at that time of the year. In summer, when the moisture content of the plants drops, they prefer succulent plants and also base their migration on the growth of these plants. In very dry summers, when the vegetation and also the succulents dry out, they collect at the watering holes and wander far and wide in search of water. If the water points are not too far away, they drink once or twice a day in dry periods, otherwise the animals can get by for several days without access to water. Saigas are able to drink even salty water. Saigas are good swimmers and can cross wide streams like the Volga .

Social behavior, migration, and reproduction

Saigas are diurnal for most of the year. In summer, however, they prefer the morning and evening hours and rest at noon. The animals are not loyal to their place and often migrate several tens of kilometers a day. When hiking from the northern summer areas to the southern winter quarters and back, you can cover 80 to 120 kilometers in one day. They move in a long row, while grazing they move across a broad front. Extensive hikes occur particularly in winter years with unfavorable living conditions. Then there will also be regular mass deaths, from which the populations can quickly recover under natural conditions. The saigas' migratory movements are not fixed in terms of time or space, and they do not occur in the entire distribution area. In Mongolia, for example, no seasonal migration has yet been observed. Rather, they are based on the availability of life resources.

Saigas are gregarious and live in herds of around thirty to forty animals in the summer. Large migrating herds with thousands of animals often form in spring and autumn. During the mating season, which is in December and January, the bucks try to gather a harem of females around them. The size of the harems depends on the fighting strength of the respective buck and on the gender ratio. Usually there are 5 to 10 females per buck, but it can be up to 50. Because of the heavy hunting for their horns, the number of saiga bucks decreased rapidly at the beginning of the 21st century. This led to the fact that in the year 2000 a buck was surrounded by innumerable females, and thus to a complete reversal of social behavior. The females began to drive weaker members of the sex away from the goats, which apparently led to a large number of unfertilized females and ultimately to the collapse of the populations. Usually, however, the females behave largely peacefully with one another. The bucks, on the other hand, are extremely aggressive during the mating season and are covered with skin gland secretions, foamy saliva and not infrequently with the blood of their wounds. It even happens that they attack people at this time. Then they hardly eat and at most ingest large amounts of snow. The fights for the females, which the bucks carry out among themselves, often end with death or serious injuries. The emaciated animals also become extremely careless and easy prey for predators. As winter progresses, many saiga bucks are so weakened from the constant fighting that they die from exhaustion.

At the beginning of spring, the male saigas gather west of the Caspian Sea in herds of 10 to 2000 animals and move north. The female saigas form large herds here and give birth to their young in April or May, each weighing around 3.5 kg. Two thirds of pregnant females give birth to twins, the rest give birth to individual young. After a few days they will start to eat grass, but they will be breastfed for at least another four months. As soon as the young can walk well enough, the females also follow the males and move north in huge herds. These can include several hundred or thousands of individuals; the largest saiga herd ever observed was estimated at 200,000 animals in 1957. In the summer the large herds split up again and the smaller associations emerge. Females are sexually mature at just under one year of age, males a little later. The maximum age of a female saiga in the wild is twelve years; Although male animals can theoretically live to be just as old, they usually die from struggle or exhaustion when they are just a few years old.

Natural enemies

Apart from humans, wolves are the saigas' main enemies. Since there is no cover in their habitat , the saiga's main defense is their speed of escape. This can be up to 80 km / h. These high escape speeds make it difficult for wolves to hunt healthy saigas. Therefore, weakened males, highly pregnant females and young animals in particular fall victim to them. A high snow cover also favors the wolves' hunting success on saigas. Newborn saigas can also pose a threat to eagles, ravens, and red foxes. The most common disease, which occasionally leads to massive deaths, is foot-and-mouth disease , but this type of antelope is also affected by a large number of other parasites and pathogens.

Distribution and population development

Original spread

The saiga was a character animal of the last ice age . In the Pleistocene it was widespread in the cold steppes of Europe and Asia and had even crossed the land bridge over today's Bering Strait and settled in Alaska and northwestern Canada. In 1976, her bones were found in the Bluefish Caves in the northern Yukon in a 13,000 year old deposit. In western Europe it even reached the British Isles during the cold ages. At the end of the Ice Age, the area of distribution shrank due to the spreading forest. The saiga disappeared from Central Europe in prehistoric times. Historically, the area of distribution still extended from the plains bordering the Carpathian Mountains to the foothills of the Altai Mountains , to Djungary and western Mongolia. The saiga inhabited almost all of Europe and large parts of the Asian steppe and forest steppe belt, although it only penetrated the latter in summer and not every year. Hilly or even mountainous areas were not part of their habitats.

Distribution area up to the 18th century

As recently as the 18th century, the westernmost deposits existed at the foot of the Carpathian Mountains on the southern Prut River around 25 degrees longitude. At the northwesternmost end of the distribution area, it reached the 50th parallel in the north. The northern limit of distribution in Europe ran just south of Kiev via Kursk and Samara to Ufa . At Ufa, in some years they even reached 55 degrees north latitude. In the south, saigas were still widespread as far as the Black and Azov Seas in the 18th century , but were absent in the Crimea, where the species only survived until the 13th century. In the western Caucasus it reached the Kuban River in the south . In the east it even reached the foot of this mountain on the lower Terek . How far it advanced there on the shores of the Caspian Sea to the south, however, is not exactly known; the range here probably extended to Derbent . Further south, saigas in this area have only been proven by prehistoric fossil finds. The Asian distribution area was not yet affected at this time.

Development of the distribution area since the 18th century

In the 18th century it gradually disappeared from the northern and westernmost areas of its European range when it was increasingly populated by humans. To the east of the Volga and the Ural Rivers, however , the area of distribution was apparently not yet reduced by the end of the 18th century. In the north they still occurred at that time on the Samara River and as far as Orenburg . Farther east they were widespread in the north as far as Ishim , in the Barabasteppe (as a summer guest) and on the Ob. Even further to the east, the northern border lay at the foot of the Altai and ran across the Saissan plain to Djungaria and western Mongolia. The southern limit of distribution extended from the lower Amur Darja and the middle Syr Darja at about 44 degrees north along the Karatau Mountains and the Ili River valley to China. They were missing in the Djungarian Alatau and the Tarbagatai Mountains.

In the 19th century, the European distribution area continued to shrink and up to the middle of that century only individual animals could occasionally be detected west of the Don and north of Volgograd. The southern border hardly changed at that time. At the beginning of the 20th century, the stocks continued to decline dramatically, mainly due to heavy hunting, and in the 1920s and 1930s there were only a few isolated residual deposits. The total population at that time is estimated to be less than a thousand animals. After the saiga was almost exterminated, it was placed under complete protection by the Soviet Union in 1923 . After this, the population recovered to such an extent that by the mid-1950s, two million saigas were once again living in what was then the USSR. At that time it was able to expand its range in the west to the foot of the Caucasus, in the north to Volgograd and Orsk . Regulated hunting of the stocks was even allowed again.

Younger population development, endangerment and protection status

| population | Stock size 2003 | Stock size 2010 |

|---|---|---|

| Kalmukia | 10,000-20,000 | |

| Ural | <10,000 | 27,000 |

| Ust-Urt | > 10,000 | 5,000 |

| Betpak Dala | 2,000-3,000 | 53,000 |

| Mongolia | 750 | approx. 8000 |

| total | approx. 20,000 | approx. 100,000 |

Since the 1970s, however, the numbers have fallen again drastically due to habitat loss, poor management, excessive hunting and poaching. The collapse of the Soviet Union also ensured that the protective provisions were no longer observed. Because there is a strong demand for the supposedly healing horns of the males in traditional Chinese medicine and the buyers are willing to pay extremely high prices, all stocks collapsed to an unexpected extent due to poaching. Because there were no more males in whole regions, the animals remained without offspring. In Kazakhstan alone , stocks fell from 1.2 million to 30,000 within a few years. The total population of the nominal subspecies ( Saiga tatarica tatarica ) was estimated at 26,000 around the year 2000, which led the IUCN to change the status of the subspecies and thus the entire species from lower risk to critically endangered (threatened with extinction ) in 2002 ) to change. Currently they can only be found in the Russian Kalmyk steppe and in three areas of Kazakhstan. It is extinct in China and southwestern Mongolia.

Censuses made from the air in 2016 showed a total population of approximately 108,300 adult Kazakh saiga. These stocks are divided into three populations. The so-called Ural population in the area of the river of the same name is 70,200 individuals (2015: 51,700), a second population can be found in the area of the Ust-Urt plateau with 1,900 individuals (2015: 1,200), and a third in the hunger steppe ( Betpak Dala ) with 36,200 individuals. All three individual populations migrate between their summer pastures and their winter quarters. The protection of the saiga therefore requires large-scale protection concepts. Some of the herds of the hungry steppe overwinter in the Andasai nature reserve . The litter pitches and summer pastures, on the other hand, are further north and are partly protected by the Irgyz Turgay nature reserve . Chornye Semli is an important reserve for the Russian population in Kalmukia . The saiga is still protected in Russia and Kazakhstan, but the implementation of these provisions is poor.

The populations of the second subspecies, the Mongolian Saiga ( Saiga tatarica mongolica ), are even smaller, but not so much in decline. Their population numbers were estimated at only around 750 in January 2004, most of which live in the area of the Sharga nature reserve , a semi-desert basin north of the Gobi Altai, and in the Manchan District, south of Lake Char Us Nuur in north-west Mongolia. Since the population has also decreased significantly in recent years due to poaching and harsh winters, this subspecies is classified as endangered (critically endangered). By 2016 the population was able to recover to 10,000 animals, but was decimated again by diseases. It is estimated that there were around 7,500 Mongolian saiga in 2017. The western subspecies of the saiga was once found in the south-west of Mongolia, but has become extinct here.

mass extinction

After the number of saiga had increased to around 250,000 individuals by 2014, the population in Kazakhstan suffered a puzzling mass extinction in 2015 , which according to various estimates killed 120,000 to almost 200,000 animals. In 2016, hemorrhagic septicemia was determined to be the cause of death and the bacterium Pasteurella multocida was identified as the cause of the mass deaths. Since Pasteurella multocida is also found in healthy animals, it was unclear for a long time why so many animals were killed by the bacterium in a short time. Recent research comparing weather data from 2015 with further mass extinctions in 1981 and 1988 suggest that climatic conditions determine whether the bacterium is fatal to the saiga on a large scale. In all three periods, the temperature and humidity in Kazakhstan were unusually high, which could have caused a toxic change in Pasteurella. The 2015 mass extinction, however, was by far the most devastating for saiga populations. Scientists therefore suspect that the saiga is particularly vulnerable to temperature changes that are favored by climate change.

The plague of small ruminants also poses a threat to the saiga population. In Mongolia, around 2,500 animals fell victim to the disease between December 2016 and February 2017, which meant a 25% reduction in the total population of the Mongolian saiga. Since the disease is spread from farm animals to wild animals, livestock in the affected regions have been vaccinated to prevent further spread.

Keeping in captivity

Saigas are now rarely kept in European zoos. A larger breeding group of the Kazakh saiga ( S. tatarica ) lives in Askanija-Nowa in the Ukraine .

Systematics and tribal history

The origin of the genus is obscure and fossil finds are only known from the Pleistocene. They are already very similar to today's species. When it was first described, the saiga was assigned to the goat-like , later to the gazelle-like . To get around the problem, a subfamily Pantholopinae is sometimes formed for the Saiga and the equally controversial Tschiru . However, new molecular genetic studies give rise to the assumption that the classification of the saiga among the gazelle-like species is correct and that the chiru belongs to the goat-like species.

The Mongolian form of the Saiga was originally described as a separate species, but today it is usually considered a subspecies ( Saiga tatarica mongolica ) of the Saiga. In the meantime it was partially considered a subspecies of Saiga borealis , which is usually used to describe an Ice Age form of the Saiga . Genetic studies can clearly separate both the Saiga and the Mongolian Saiga from one another, but show only a small genetic distance, which in the opinion of the authors rather suggests that the Mongolian Saiga is actually only a subspecies. Using morphological data, the two forms can be easily distinguished. This applies above all to the horn design: Compared to the Saiga, the Mongolian Saiga has shorter and slimmer horns without clearly pronounced fluting. A revision of the hornbeams from 2011 therefore regards them again as separate species.

Benefits and harm to humans

Saigas have been hunted for their skins and meat since ancient times. The horns are used in Chinese medicine and fetch high prices that are comparable to those of the rhinoceros nasal horn. Enormous quantities of saiga horns were imported into China in the 18th century. Hundreds of thousands of saigas were shot annually in Russia in the 19th century. Most of the time, the herds were driven into a funnel-shaped enclosure made of reeds and earth. At the narrowing end, sharpened stems waited for the fleeing animals on which they impaled. In winter, they were also driven onto smooth, frozen lakes, where the animals were helpless. Hunting through pitfalls and with the help of trained eagles was also common at the time. Hunting was generally banned in 1919, but when the numbers rose sharply again in the 1950s, the animals were again hunted commercially.

Especially in summer, in the dry season, saigas damage harvests, often trampling more than they eat when wandering through the fields. Still, the damage is often greatly exaggerated, and when it was more common, the gains from hunting exceeded the losses from crop damage. Whether they compete seriously with grazing animals such as sheep has not yet been thoroughly researched, but due to the pronounced migratory behavior of the saiga and their preference for plants that are spurned by sheep, it should not be too great.

On the other hand, the saiga contribute significantly to the preservation of the natural steppes and the grasslands through their herd-like appearance and the “trampling” of the upper soil horizons .

Young saigas can be tamed easily. Especially if they were raised at just 5–6 days old, they become quite affectionate and often return to the farm of their foster parents even when they are free to run around.

Representations in Ice Age art

Saiga antelopes also play an important role in the art of the last Ice Age. The oldest representations are known from the late Upper Paleolithic , around 14,000 years ago.

The head in particular, with the nose section characteristic of Saigas, can be found as an engraving on bones and stone slabs and as a motif for wall paintings from that era. Almost all known representations come from Paleolithic sites in France and Spain. For example, two engravings from the cave of Altxerri near San Sebastian are known , where two horned heads of saigas were juxtaposed. The only find so far from Germany comes from a Magdalenian-Age storage site excavated near Gönnersdorf by Ice Age hunters. It is a sketchy representation of the front part of the nose of a saiga that was scratched on a Devonian slate.

A figurative representation is known from the Enlène cave in France. A sculpture carved out of bones from the Middle Magdalenian was found here. It was once used as the barb end of a spear thrower .

In the novel The Place of Execution by Tschingis Aitmatow , the hunt for saigas plays a central role in the years of the Soviet Union .

Web links

- NABU cartoon for the protection of the saiga antelope

- Saiga Conservation Alliance (international network for the conservation of the Saiga)

- GEO: video and information

literature

- Ronald M. Nowak: Walker's Mammals of the World . Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8018-5789-9

- VG Heptner: Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol. I Ungulates . Leiden, New York, 1989, ISBN 90-04-08874-1

- DE Wilson & DM Reeder: Mammal Species of the World . Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-8018-8221-4

Individual evidence

- ^ Saiga Antelope - Saiga tatarica. 2015 Large Herbivore Network / ECNC

- ↑ EJ Milner-Gulland et al .: Reproductive collapse in saiga antelope harems . Nature , Volume 422, March 13, 2003. ( PDF )

- ↑ Large Herbivore Network: Saiga Antelope Saiga tatarica

- ^ Mallon, DP 2008. Saiga tatarica . In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1. (Downloaded on October 29, 2011)

- ^ EJ Milner-Gulland et al .: Dramatic decline in saiga antelope populations . Oryx, Vol 35, No 4, October 2001 online-PDF ( Memento of the original from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ After mass die-off, saiga antelope numbers go up in Kazakhstan. Retrieved January 18, 2018 (American English).

- ↑ Mallon, DP and Kingswood, SC (compilers). (2001). Antelopes. Part 4: North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Global Survery and Regional Action Plans. SSC Antelope Specialist Group. IUCN, GLand, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. ISBN 2-8317-0594-0

- ^ IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Saiga tatarica mongolica online

- ^ A Deadly Virus is Killing Saiga Antelope in Mongolia> WCS Newsroom. Retrieved January 18, 2018 (American English).

- ↑ Ralf Nestler: Saiga antelopes: Enigmatic mass extinction in Kazakhstan at tagesspiegel.de, accessed on June 4, 2015.

- ↑ Mysterious mass extinction: 120,000 saiga antelopes perish at n-tv.de, accessed on June 4, 2015.

- ↑ Mass extinction of the saiga antelopes: 40 percent of the total world population at nabu.de, accessed on November 6, 2015.

- ↑ Mass deaths of saiga antelopes due to bacteria nzz.ch from April 22, 2016, accessed on May 20, 2016.

- ↑ The cause of mass deaths still unclear Spektrum.de from September 7, 2015, accessed on May 20, 2016.

- ↑ A saiga time bomb? Bad news for Central Asia's beleaguered antelope. Retrieved January 18, 2018 (American English).

- ↑ Richard A. Kock, Mukhit Orynbayev, Sarah Robinson, Steffen Zuther, Navinder J. Singh: Saigas on the brink: Multidisciplinary analysis of the factors influencing mass mortality events . In: Science Advances . tape 4 , no. 1 , January 1, 2018, ISSN 2375-2548 , p. eaao2314 , doi : 10.1126 / sciadv.aao2314 ( sciencemag.org [accessed January 18, 2018]).

- ^ A Deadly Virus is Killing Saiga Antelope in Mongolia> WCS Newsroom. Retrieved January 18, 2018 (American English).

- ↑ Entry on Saiga tatarica on zootierliste.de

- ^ Maria V. Kuznetsova & Marina V. Kholodova: Molecular Support for the Placement of Saiga and Procapra in Antilopinae (Artiodactyla, Bovidae) . Journal of Mammalian Evolution , Volume 9, Number 4 / December 2002 doi: 10.1023 / A: 1023973929597

- ↑ > Anna A. Lushchekina, S. Dulamtseren, L. Amgalan and Valery M. Neronov: The status and prospects for conservation of the Mongolian saiga Saiga tatarica mongolica. Oryx 33 (1), 1999, pp. 21-30, doi: 10.1046 / j.1365-3008.1999.00032.x

- ^ Joel Berger, Julie K Young, and Kim Murray Berger: Protecting Migration Corridors: Challenges and Optimism for Mongolian Saiga. PLoS Biol 6 (7), 2008, p. E165 doi: 10.1371 / journal.pbio.0060165

- ↑ G. Baryshnikov and A. Tikhonov: Notes on the skulls of Pleistocene Saiga of Northern Eurasia. Historical Biology 8, 1994, pp. 209-234

- ↑ NA Lushchekina * and S. Dulamtseren: The Mongolian Saiga: Its Present Status and Preservation Outlook. Izv Akad Nauk Ser Biol. 2, 1997, pp. 177-185

- ↑ A Note prepared by Dr. Torbjörn Ebenhard: Regarding the Taxonomy and Nomenclature of Mammals Listed on the Appendix of the CMS , Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals, CMS ( online PDF ( Memento of the original from October 8, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: Der Archivlink was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note. )

- ↑ MV Kholodova, EJ Milner-Gulland, AJ Easton, L. Amgalan, Iu. A. Arylov, A. Bekenov, Iu. A. Grachev, AA Lushchekina and O. Ryder: Mitochondrial DNA variation and population structure of the Critically Endangered saiga antelope Saiga tatarica. Oryx 40 (1), 2006, pp. 103-107, doi: 10.1017 / S0030605306000135

- ↑ Colin P. Groves and David M. Leslie Jr .: Family Bovidae (Hollow-horned Ruminants). In: Don E. Wilson and Russell A. Mittermeier (eds.): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 2: Hooved Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2011, ISBN 978-84-96553-77-4 , pp. 631-632

- ↑ Colin Groves and Peter Grubb: Ungulate Taxonomy. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011, pp. 1–317 (p. 157)

- ↑ C. Dubourg et al .: Un block grave de l'abri de la Souquette. Une nouvelle figuration d'antilope Saïga. Paleo Volume 6, Sergerac, Dordogne 1994. pp. 247-259, Fig. 7f. Digitized

- ^ Gerhard Bosinski : The excavations in Gönnersdorf 1968–1976 and the settlement findings from the excavation in 1968. With contributions by David Batchelor. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1979, ISBN 3-515-02509-X .

- ^ R. Bégouen et al .: Le propulseur au saiga dÉléne. In: Préhistoire ariégeoise. Bulletin de la société préhistorique Ariège-Pyrénées, 1986. pp. 11-22.