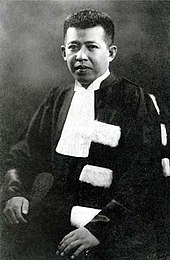

Pridi Phanomyong

Pridi Phanomyong ( Thai : ปรีดี พนม ยง ค์ , pronunciation: [ priːdiː pʰánomjong ], alternative transcription Banomyong , until 1942 feudal honorary title Luang Praditmanutham (short Pradit ); * May 11, 1900 in Ayutthaya ; † May 2, 1983 in Paris ) was a Thai lawyer and politician. He was one of the founders of the constitutionalist people 's party and one of the main promoters of the Siamese Revolution , which brought the country from absolute to constitutional monarchy in 1932.

Pridi represented liberal and socialist- inspired ideas. From 1936 to 1938 he was Foreign Minister, then Thailand's Minister of Finance. From 1941 to 1945 he was one of the regency councilors who represented the underage King Ananda Mahidol . During World War II , he was a leader in the Seri Thai movement that resisted the Japanese . Between March and August 1946 he ruled as Prime Minister of Thailand .

life and career

Origin and education

Pridi was born in Ayutthaya, the son of Siang and Lukchan. Family names were not yet introduced in Siam at that time . The family later took the name Phanomyong because their ancestors had lived near the temple (Wat) Phanomyong in Ayutthaya and Siang, like several of his male ancestors, had lived in this monastery for a time as a monk. On his father's side, Pridi was partly of Chinese descent . He was the second of eight siblings.

Since there was still no secondary school in his home province, he went to Bangkok at the age of 10 to attend the temple school of Wat Benchamabophit.In 1912 he switched to the newly opened experimental school of Monthon Krung Kao, the first secondary school in Ayutthaya and later to the prestigious Suankularb Wittayalai School in Bangkok. At the age of 17 he began studying at the law school of the Thai Ministry of Justice. He completed his training in just two and a half years and was admitted to the bar at the age of 19. Upon graduation, he lived in the home of Phraya Chaivichit-Visidthamathada, a senior official in the Justice Department and son of the former Ayutthaya governor, to whom he was distantly related. After winning his first case, which was considered sensitive for accidentally damaging Crown property, Phraya Chaivichit appointed him as a clerk in the Justice Department's Department of Justice.

In 1920 Pridi received a grant from the Ministry of Justice to study in France, where he studied law and political economy at the University of Caen and the University of Paris ( Sorbonne ) in Paris . Pridi's thinking was influenced by the tradition of French liberalism and partly also by European socialism. He was elected President of the Siamese student organization in France ( association Siamoise d'intellectualite et d'assistance mutuelle , SIAM) in 1925. In January 1926 he received the Diplôme d'études supérieures (DES) in political economy.

In France he got to know Prayun Phamonmontri . Together with five other students and young military personnel (including Plaek Khittasangkha , who was later called Phibunsongkhram), they founded the Siam People's Party (Khana Ratsadon) in Paris in February 1927 , which sought an end to absolute monarchy and the transition to constitutionalism . In the same year Pridi was awarded a doctorate in law by the University of Paris with a comparative law dissertation on the fate of partnerships in the event of the death of a partner.

Government career and revolution

After graduating, Pridi returned to Thailand and worked in the Ministry of Justice , where he rose rapidly. In 1928 he married the then 16-year-old daughter of his mentor Phraya Chaivichit, who was almost twelve years younger than Poonsuk Na Pombejra ( พูน ศุ ข ณ ป้อม เพชร ). The two had four daughters and two sons. Poonsuk accompanied him throughout his life and also shared his political commitment.

At the age of 29 he received the feudal honorary title Luang Praditmanutham ( หลวงประดิษฐ์ มนู ธรรม ; older legend : Pradist-Manudharm ), under which he was known until the abolition of the titles and ranks in 1942. The name chosen by Pridi himself means "to practice humanity". From 1930 Pridi published the collection of Thai laws as an aid for lawyers , as the sometimes very old legal norms were often difficult to find before. The volumes sold very well. The income enabled him to set up his own small printing company. He was also hired as a lecturer at the Ministry of Justice's law school. His lectures in administrative law attracted particular attention there. In these he already outlined constitutional principles, discussed political economy and public finance and was the first to teach principles of modern governance in Siam. With his influence on the students, Pridi contributed to the growing awareness of sections of the bourgeoisie for political rights and participation.

During this time, Pridi was instrumental in preparing a coup to abolish absolute rule in Thailand, which should lead to a constitutional monarchy . This coup took place on June 24, 1932, and ended shortly afterwards with the adoption of the Provisional Constitution drawn up by Pridi by King Prajadhipok (Rama VII) . Pridi became a member of the cabinet known as the "Public Committee" and Minister of Finance.

Economic plan

In January 1933, Pridi proposed an economic plan known as the "yellow notebook" ( samut pok-lueang ). It envisaged the nationalization of all arable land, the industrialization of the land and state ownership of the means of production. All Siamese should become government employees, be paid by the government, supported in illness and old age and also take part in the administration. The nationalization of the companies should not take place through expropriation, but in exchange for state securities. The Prime Minister Phraya Manopakorn Nititada and his conservative wing in the government rejected this plan, as did King Prajadhipok, as "communist". The King dissolved the National Assembly, saying:

“I don't know whether Stalin copied Luang Pradit or whether Luang Pradit copied Stalin. […] The only difference is that one is Russian and the other is Thai. […] This is the same program that was used in Russia. If our government accepted it, we would help the Third International to achieve the goal of world communism. [...] Siam would be the second communist state after Russia. "

In fact, the plan was influenced less by Soviet than by Western European, especially French, ideas of state-led industrial policy and the welfare state . Pridi also cited traditional Buddhist ideals of a just society to support her, which are reflected, for example, in the utopian and millenarian ideas of the coming era of Buddha Maitreya , in which people should live free from material worries. He also argued that there was also a tendency towards nationalization in the most important Western European countries at the time, for which he followed the policies of the British Labor government Ramsay MacDonald , the center-left coalition Édouard Daladier in France and the one shortly before that came National Socialist government of Adolf Hitler in Germany.

Nevertheless, the plan met with resistance even from some of Pridi's supporters in the People's Party. His college friend Prayun Phamonmontri published an article together with the conservative Phraya Manopakorn in which they condemned the concept. The Cabinet declared a state of emergency on April 1, 1933, and passed a "Law Against Communist Activities," although there was virtually no communist activity in Siam at the time. Rather, the regulation was directed against the reforms in Pridi's economic plan, which, according to the deliberately broad interpretation of the law, could be understood as “communist”.

Manopakorn's Conservatives pushed Pridi into exile. While saving his face, the Prime Minister suggested a study visit to Europe with a government grant of 1000 British pounds a year. Pridi, realizing that he had no alternative, accepted and chose France. When he and his wife left on April 12, hundreds came to the port to see them off, including ministers and MPs from the People's Party including Phraya Phahon Phonphayuhasena and Plaek Phibunsongkhram.

Terms of office as ministers

Less than two months after their arrival in Europe , younger members of the People's Party around Phibunsongkhram launched a coup against the Phraya Manopakorn government in June 1933 . Phraya Phahon became the new Prime Minister and Pridi was able to return to Siam, where he arrived at the end of September 1933. In February 1934 a committee of inquiry was convened into Pridi's alleged communist activities. Before this, however, he was able to explain his views and was finally acquitted of all allegations unanimously. Subsequently, at the end of March 1934, Pridi was appointed Minister of the Interior , and he held the office until February 1935.

In 1934, Pridi was one of the founders of Thammasat University in Bangkok and also its first rector. It was the second university in the country and, unlike the older Chulalongkorn University, was not founded by the king, but through civic engagement. It was initially specialized in law and political science and was intended to train a new generation of civil leaders. He was the rector of the university until 1949.

In July 1936 Pridi became Siams' Foreign Minister. In this capacity, he concluded friendship treaties between Siam and 13 other nations, including the USA, Great Britain, Japan, Italy, France and Germany, in 1937. This replaced the so-called unequal treaties from the 19th century, through which the major European powers had secured extraterritorial rights for themselves and their nationals in Siam. This gave Siam unrestricted sovereignty over its territory and foreigners staying in the country had to submit to local jurisdiction. At the same time, in the negotiations with Japan, he rejected any wish of the new Asian great power for special rights and insisted on the strict neutrality of Siam. In the following years he was honored with the highest foreign honors, including Adolf Hitler , leader of the National Socialist German Reich , awarded him the Grand Cross of the German Eagle Order in April 1938 ; in February 1939 he was awarded the Grand Cross of the French Legion of Honor .

In December 1938, Pridi moved to the government of Plaek Phibunsongkhram to head the Ministry of Finance. From an ally of Phibunsongkhrams he developed into a critic and rival of the increasingly authoritarian ruling prime minister. In particular, Pridi and his supporters criticized armament and militarization. Nevertheless, the prime minister valued him as an able minister and kept him in government. The relationship between the two can be described as a "hate friendship".

In view of the beginning of World War II, Pridi wrote the historical novel Phra Chao Chang Phueak (English The King of the White Elephant ) about a fictional Siamese King Chakra, whose figure is loosely based on the historical King Chakkraphat from the 16th century. He idealized this as a popular, self-sacrificing and peaceful leader. Due to the description of one of the numerous wars of the Siamese kingdom Ayutthaya with the neighbor Burma, the Thais should learn from the "stupidities of their ancestors". He had the book filmed in English in 1940. He wanted to illustrate his and Thailand's peace-loving intentions towards the international community. At this time, Pridi was said to have ambitions for the Nobel Peace Prize . In Thailand, however, he became more and more the "lonely voice" against the wave of nationalism propagated by Phibunsongkhram and his allies.

In protest against the alliance between the Phibunsongkhram government and Japan (forced by a threatened Japanese invasion), Pridi resigned as finance minister in December 1941.

Crown regent and "experienced statesman"

Immediately thereafter, Phibunsongkhram Pridi was appointed to the three-member Regency Council for the minor king Ananda Mahidol (Rama VIII) . The declaration of war by Thailand on Great Britain and the USA , pronounced in January 1942 under Japanese pressure, was not signed by Pridi. While the head of government nevertheless declared them valid, the Thai ambassador to Washington, DC , Seni Pramoj , refused to deliver them to the US government . After the end of the war, Thailand claimed that there had never been a valid declaration of war. After the abolition of feudal titles and ranks in 1942, Pridi gave up his Luang title and returned to his real name.

During this time, Pridi formed the Seri Thai movement , a movement for a free Thailand, directed against the de facto Japanese occupation , in collaboration with Seni Pramoj, who directed the movement from abroad with British and American support. After the death of Chao Phraya Bijayendrayodhin in 1942 and the resignation of Prince Aditya Dibabha in 1944, no new regents were appointed, so that Pridi was the only one who remained. After Phibunsongkhram was voted out of office in July 1944, Khuang Aphaiwong took over the government. While this apparently continued to work with the Japanese, Pridi cooperated with the Allies . His office as Regency Council functioned effectively as the headquarters of the resistance in Thailand, presumably with the tacit approval of the Prime Minister.

Immediately after the Japanese surrender on August 15, 1945, Pridi revoked the Phibsunsongkhram government's treaties with Japan and declared the declaration of war on Great Britain and the United States null and void. When King Ananda came of age and returned to Thailand in December 1945, his role as regent became obsolete. He was awarded the highest order ( Order of the Nine Precious Stones , Order of Chula Chom Klao first class) and received the honorary title of "experienced statesman" ( รัฐบุรุษ อาวุโส , Ratthaburut Awuso) created just for him . He acted as an advisor to the post-war governments of Thawi Bunyaket and Seni Pramoj and was seen as their strong man in the background.

Term of office as Prime Minister

After his supporters had won many mandates in the first post-war election in January 1946, Pridi Phanomyong took over the post of Thai Prime Minister himself on March 24, 1946; he was the seventh holder of this office. Pridi's government relied on the left-wing "cooperative party" (Sahachip), formed primarily by former Seri Thai fighters from the northeast region , and the "constitutional front " that emerged from the liberal wing of the former Khana Ratsadon, as well as non-party members. During his reign a new constitution was enacted on May 9, 1946, one of the most liberal and most democratic in Thai history.

Exactly one month later, King Ananda Mahidol died on June 9, 1946 under unexplained circumstances (accident, murder or suicide), so that Pridi had to formally resign on June 11, but then again by the new King Bhumibol Adulyadej (represented by his regent Prince Rangsit Prayurasakdi ) was used. During this time his political opponents, especially from royalist circles, deliberately spread the rumor that Pridi was somehow responsible for the death of the young king. They imputed republican aspirations to him.

In by-elections in August 1946, the Pridi supporting parties suffered significant losses. He resigned on August 21, citing exhaustion as the official reason. He was succeeded by Thawan Thamrongnawasawat , an ally of Pridi. The government continued to be supported by its supporters, who, however, only had a thin majority in parliament or, after the defeat of some MPs in early 1947, no majority at all. From November 1946 to February 1947, Pridi traveled through North America and Europe with his wife Poonsuk. In December 1946, the US government awarded Pridi the Medal of Freedom for his services in the resistance against Japan . When he returned to Bangkok, he was greeted by an enthusiastic crowd.

In September 1947, at the instigation of Pridis and Tràn Văn Giàu , the Southeast Asian League was founded in Bangkok , an amalgamation of anti-colonial and anti-imperialist organizations from Burma, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, the Philippines, Malaya, Indonesia and Thailand. These had fought against the Japanese occupation during the Second World War and were now directed against the continued or returned rule of the European colonial powers. It campaigned for the national independence of the peoples involved and for economic cooperation between them. The Democratic Republic of Vietnam ( Việt Minh ), Lao Issara and the Indonesian national movement had had information and arms procurement offices in Bangkok since Pridi's reign. Since there were communist tendencies in some of the movements involved, especially the Việt Minh, Pridi's political opponents in his own country - especially the Thai military - accused him of being a communist as well and a Siamese republic as the cornerstone of a pro- Soviet "Southeast Asian" Union ”.

Disempowerment and exile

On November 8, 1947, members of the army around Field Marshal Phin Choonhavan and Colonel Kat Katsongkhram (once a member of the People's Party and an ally of Pridi), with the approval of Phibunsongkhram and the opposition Democratic Party of Khuang Aphaiwong, carried out a coup against the Thawan Thamrongnawasawat government. As a result, Pridi and the camp of his supporters were finally ousted from power. At first they considered undertaking a counter-coup and again disempowering the subversive, but decided against it. Since Pridi had to fear for his freedom, maybe even his life, he fled the country. With the help of the British and American naval attaché , he was brought onto a Shell oil tanker that was just leaving the port and which drove him to Singapore (then still a British colony). The support of the former Western Allies may have been motivated by Pridi's alliance with them during World War II, but also by the thought that Pridi's absence would reduce the risk of violent clashes between the warring camps in the country.

In Singapore he was welcomed by the British Plenipotentiary General for Southeast Asia and received political asylum. From there, on November 27, he made a radio address to his supporters in Thailand, calling on them not to offer any violent resistance against the new rulers. Some British politicians, who saw Pridi as a friend of Great Britain, campaigned for him to move to England. The home office also agreed. In view of the outbreak of the Cold War, Great Britain and especially the USA increasingly sympathized with the strictly anti-communist coup plotters and it was only a matter of time before they recognized them as the legitimate government of Thailand, making Pridi their most prominent opponent a burden and an undesirable person has been. In addition, it could not be ruled out that Great Britain would extradite Pridi to the Thai rulers if they bring charges against him.

He obtained a diplomatic passport and visa from his friends and allies, Direk Jayanama and Sa-nguan Tulalak , who were still serving as ambassadors in London and Nanking, and finally traveled to China via Hong Kong in May 1948. After Phibunsongkhram had ousted the civilian prime minister Khuang Aphaiwong in April 1948 and became head of government again, his government issued an arrest warrant for Pridi in June 1948 for his alleged involvement in the murder of King Ananda Mahidol.

After a return and an unsuccessful attempted coup against Phibunsongkhram in February 1949, he went into exile again, until 1970 he lived in the People's Republic of China . According to his memoirs and those of his private secretary Sujit Suphannwat, Pridi took part in the founding celebrations of the communist state on October 1, 1949, and stayed as a guest for 21 years. During the mass arrests of members of the peace movement and actual and alleged communists in Thailand at the end of 1952, Pridi's wife Poonsuk, who had stayed behind at home, and his eldest son Pal were also arrested. Poonsuk was released after 84 days in custody and immediately went to France with two of her daughters, later they followed Pridi to China. In 1955 the family moved from Beijing to Guangzhou (Canton). Pal was not given an amnesty until 1957.

In 1957, towards the end of Phibunsongkhram's reign, the Prime Minister sent a messenger to Pridi to inform him of new evidence regarding the death of King Ananda and to offer him a fair trial. Pridi planned to face this and prepared to return to Thailand, but broke it off when he learned of the seizure of power in October 1958 by Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat , who ruled at least as authoritarian as Phibunsongkhram in the following years. Pridi continued to closely follow political events in Thailand, even if the news from his home country gave him no hope.

From 1970 until his death he lived in France, where he wrote his memoirs ( Ma vie mouvementee et mes 21 ans d'exil en Chine populaire ; "My eventful life and 21 years in exile in the People's Republic of China"). In these he summed up, among other things, about his political life: "When I had power, I had no experience, and when I was more experienced, I had no power."

Pridi Phanomyong died of a heart attack in Paris on May 2, 1983 .

literature

- National Economic Policy of Luang Pradist Manudharm (Pridi Banomyong). Edited by Kenneth Perry Landon. Committees on the Project for the National Celebration on the Occasion of the Centennial Anniversary of Pridi Banomyong, Senior Statesman (private sector), 1999.

- Pridi Banomyong: Pridi by Pridi. Selected Writing on Life, Politics, and Economy. Translation and introduction by Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit. Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai 2000, ISBN 9747551357 .

- Volker Grabowsky : Small History of Thailand , CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60129-3 .

- Vichitvong Na Pombhejara: Pridi Banomyong and the making of Thailand's modern history. 2nd Edition. Committees on the Project for the National Celebration on th Occasion of the Centennial Anniversary of Pridi Banomyong, Bangkok 2001.

- Martina Peitz: The elephant's tiger leap. Rent-seeking, nation building and catch-up development in Thailand , LIT Verlag, Zurich 2008.

- Sulak Sivaraksa : In the Face of Power - Pridi Banomyong. The rise and fall of democracy in Siam, Thailand. Sathirakoses-Nagapradipa Foundation, Bangkok 2005, ISBN 974-93403-4-5 .

- Judith Stowe: Siam Becomes Thailand. A Story of Intrigue , C. Hurst & Co., London 1991, ISBN 1-85065-083-7 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Vichitvong Na Pombhejara: Pridi Banomyong and the Making of Thailand's Modern History. Bangkok 1982, p. 36.

- ↑ Vichitvong Na Pombhejara: Pridi Banomyong and the Making of Thailand's Modern History. 1982, p. 37.

- ↑ Chris Baker , Pasuk Phongpaichit: A History of Thailand. Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 122.

- ↑ Vichitvong Na Pombhejara: Pridi Banomyong and the Making of Thailand's Modern History. 1982, p. 39.

- ↑ Pridi Banomyong: You sort des sociétés de personnes en cas de décès d'un associé (étude du droit français et de droit comparé). Librairie de jurisprudence ancienne et modern, Paris 1927.

- ↑ Vichitvong Na Pombhejara: Pridi Banomyong and the Making of Thailand's Modern History. 1982, p. 38.

- ↑ Vichitvong Na Pombhejara: Pridi Banomyong and the Making of Thailand's Modern History. 1982, p. 45.

- ^ Stowe: Siam Becomes Thailand. 1991, p. 13

- ↑ Vichitvong Na Pombhejara: Pridi Banomyong and the Making of Thailand's Modern History. 1982, p. 44.

- ↑ a b Erik Kuhonta: The Institutional Imperative. The Politics of Equitable Development in Southeast Asia. Stanford University Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0-8047-7083-5 , p. 138.

- ↑ a b c Grabowsky: Brief history of Thailand. 2010, p. 154.

- ↑ a b Peitz: The Elephant's Tiger Leaping. 2008, pp. 184f.

- ^ Stowe: Siam Becomes Thailand. 1991, pp. 37-38.

- ↑ Heinz Bechert: Buddhism, State and Society in the Countries of Theravāda Buddhism. Volume 1. Metzner, Wiesbaden 1966, p. 181.

- ↑ Volker Zotz : History of Buddhist Philosophy. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1996, p. 254.

- ^ Tomas Larsson: Land and Loyalty. Security and the Development of Property Rights in Thailand. Cornell University Press, Ithaca / London 2012, p. 89.

- ↑ Vichitvong Na Pombhejara: Pridi Banomyong and the making of Thailand's modern history. 1982, p. 287.

- ↑ a b Peitz: The Elephant's Tiger Leaping. 2008, p. 185

- ↑ Vichitvong Na Pombhejara: Pridi Banomyong and the making of Thailand's modern history. 1982, p. 79.

- ↑ Vichitvong Na Pombhejara: Pridi Banomyong and the making of Thailand's modern history. 1982, p. 97.

- ↑ Vichitvong Na Pombhejara: Pridi Banomyong and the making of Thailand's modern history. 1982, pp. 98-102.

- ↑ Vichitvong Na Pombhejara: Pridi Banomyong and the Making of Thailand's Modern History. 1982, p. 36.

- ↑ Nigel J. Brailey: Thailand and the Fall of Singapore. The Frustrating of an Asian Revolution. Westview Press, Boulder CO 1986, p. 89.

- ↑ Hitler Honors Siamese. In: The Straits Times , April 3, 1938, p. 3.

- ↑ Pridi Phanomyong: ชีวิต ผันผวน ของ ข้าพเจ้า และ 21 ปี ที่ ลี้ ภัย ใน สาธารณรัฐ ราษฎร จีน [Chiwit Phanphuan khong Khapachao lae 21 Pi thi Liphai nai Satharanarat Ratsadon Chin; My eventful life and 21 years in exile in the People's Republic of China], Thian Wan, Bangkok 1986.

- ^ Grabowsky: Brief history of Thailand. 2010, p. 154.

- ↑ Walter Skrobanek: Buddhist politics in Thailand. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1976, p. 163.

- ^ A b Joseph J. Wright: The Balancing Act. A History of Modern Thailand. Pacific Rim Press, Oakland CA 1991, p. 133.

- ↑ The name Siam was renamed in 1939 at the instigation of Phibunsongkhram.

- ^ Scot Barmé: Peace not War. Pridi and The King of the White Elephant. In: Woman, Man, Bangkok. Love, Sex and Popular Culture in Thailand. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham MD / Oxford 2002, p. 245.

- ^ Grabowsky: Brief history of Thailand . 2010, p. 163.

- ↑ Thamsook Numnonda: Thailand and the Japanese Presence 1941-1945. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore 1977, p. 35.

- ^ David K. Wyatt : Thailand. A short history. 2nd edition, Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai 2004, ISBN 978-974-9575-44-4 , p. 249.

- ^ Wyatt: Thailand. 2004, p. 251.

- ↑ a b Wyatt: Thailand. 2004, p. 252.

- ^ Grabowsky: Brief history of Thailand . 2010, p. 167.

- ^ Wyatt: Thailand. 2004, p. 253.

- ↑ a b Rapturous crowds welcome Pridi home. In Nicholas Grossman (ed.): Chronicle of Thailand. Headline News Since 1946. Editions Didier Millet, Singapore 2010, p. 29.

- ↑ Pridi receives Medal of Freedom in US. In: Chronicle of Thailand. Headline News Since 1946. Editions Didier Millet, Singapore 2010, p. 27.

- ^ Christopher E. Goscha : Thailand and the Southeast Asian Networks of The Vietnamese Revolution, 1885-1954. Curzon Press, Richmond (Surrey) 1999, pp. 260-261.

- ^ Wyatt: Thailand. 2004, p. 254.

- ^ Daniel Fineman: A Special Relationship. The United States and Military Government in Thailand, 1947–1958. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1997, ISBN 0-8248-1818-0 , p. 45.

- ^ A b Peter Lowe: Contending With Nationalism and Communism. British Policy Towards Southeast Asia, 1945-65. Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, p. 195.

- ↑ a b Vichitvong Na Pombhejara: Pridi Banomyong and the Making of Thailand's Modern History. Bangkok 1982, p. 261.

- ^ HM Spitzer: Thailand Since the War. In: World Affairs , Volume 114, 1951, p. 73

- ↑ Anuson Chinvanno: Thailand's Policies towards China, 1949–54. Macmillan, Basingstoke (Hampshire) / London 1992, p. 103.

- ↑ a b Vichitvong Na Pombhejara: Pridi Banomyong and the Making of Thailand's Modern History. Bangkok 1982, p. 268.

- ^ Michael Leifer: Dictionary of the Modern Politics of South-East Asia. Routledge, London / New York, 1995, ISBN 0-415-04219-4 , p. 136. Keyword “Pridi Phanomyong”.

- ↑ Pridi Banomyong, Chris Baker, Pasuk Phongpaichit: Pridi by Pridi. 2000, p. Xx.

Web links

- Kurzbiografie (English)

- Biography (Thai)

- History of Thai Prime Ministers

- Background, story about Pridi and Phoonsuk (Thai, English) , The Banomyong family (English) (PDF; 396 kB)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pridi Phanomyong |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Pridi Banomyong; Luang Praditmanutham; Luang Pradist Manudharm |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Thai politician, Prime Minister of Thailand |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 11, 1900 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ayutthaya |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 2nd 1983 |

| Place of death | Paris |