Texas City refinery explosion

The Texas City refinery explosion occurred on March 23, 2005 at 1:20 p.m. in the largest oil refinery of the British oil company British Petroleum (BP) in Texas City , a city in Galveston County , Texas . One of the largest refinery accidents in the United States , the explosion killed 15 workers and injured over 180 people. The force of the explosion shattered windows within a radius of several kilometers, the fireball and clouds of smoke were visible up to Houston, 30 miles away .

After an internal investigation report initially identified human error as the cause of the catastrophe, on the advice of the US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (CSB) , BP asked an independent eleven-member committee headed by former United States Secretary of State James Baker to review the group-wide security management. The Baker Commission presented the results of the investigation on July 16, 2007 in a 374-page report, the so-called Baker Panel Report , and uncovered devastating safety deficiencies at BP.

The publication of the Baker Report had far-reaching implications both within the Group and for safety programs in refineries, the petrochemical and chemical industries, and the regulatory authorities. Concerned by the significant deficiencies identified in the report, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), a federal agency in the United States that enforces occupational safety laws , initiated a national priority program for process safety management in refineries.

John Browne , then CEO of BP, announced his early departure from office shortly after the Baker report was published , not without pointing out the company's commitment to implement the proposals of the Baker Board. The cost of the Texas City refinery explosion was approximately $ 2 billion in damages , fines, and rebuilding and business interruption.

BP Texas City Refinery

The BP Texas City Refinery was the third largest of the 149 refineries in the United States at the time of the accident. It was built in 1934 as a Pan American Refinery and was acquired by BP on January 1, 1999 as part of its merger with Amoco . The processing capacity in January 2005 was about 27 billion liters of crude oil per year, the output of motor gasoline was about 11 billion liters per year. The refinery obtained 30% of the raw materials via pipelines and 70% by ship, 75% of the products were transported by pipeline and 25% by ship. The refinery produced about 3 percent of US gasoline needs in 2005. In 2005, around 1,800 BP employees and 800 external company employees worked at the site, which extends over 5 square kilometers, producing products such as gasoline, low-sulfur diesel fuel , kerosene , chemical raw materials and heavy oils in 29 refinery and four petrochemical processes .

safety

In the refinery there were several industrial and occupational accidents , which led to 20 deaths and several business interruptions between 1974 and 2003. Back in 2002, BP commissioned a study from A. T. Kearney consultancy to understand the facts that led to the accidents and deterioration in the refinery's workload . The AT Kearney report found one of the causes was that a top-down process was driving the allocation of funds for maintenance tasks. Through this process, budget cuts were not made with the specific needs of the refinery in mind.

In 2004 alone, three other employees died in work-related accidents. After a major explosion in March 2004 that left no one injured, BP temporarily evacuated the refinery. The police blocked the access roads and told residents not to leave their homes.

In late 2004, BP hired consultancy Telos to conduct a safety culture survey at the Texas City Refinery. Between November 8th and 30th, 2004, the consultants questioned more than 1000 employees. The consultants presented the result in the Telos report on January 19, 2005. In the report, employees expressed major concerns about the safety standards in the refinery and criticized unrealistic guidelines, insufficient training, high cost pressure, failure of safety devices and the falsification of safety protocols. The investigation also found that spending was cut without examining the impact on plant safety .

Isomerization plant

The explosion occurred in the refinery's isomerization facility built in the mid-1980s. During isomerization , straight-chain paraffins are converted into branched iso-paraffins. This increases the octane number of motor gasoline by 30 to 40 units. Mainly n-pentane and n-hexane were used as starting materials . The production capacity of this plant was 4,300 cubic meters of light gasoline per day.

The isomerization plant consisted of a desulfurization plant , a rectification column , the so-called "Raffinate Splitter Tower", which provided the raw materials for the isomerization, the isomerization reactor and a gas recirculation system. Desulfurization was carried out using the ultrafining process, a process developed and licensed by Standard Oil of Indiana for the desulfurization and hydrogenation of naphtha using a fixed bed catalyst . The isomerization reaction was carried out in a fixed bed reactor using the Penex process, a widely used process developed and licensed by Universal Oil Products (UOP). As isomerization catalysts, the method uses acidic, chloride-activated platinum - γ-alumina - catalysts . The method also uses gas recirculation.

the accident

Early morning

On the morning of March 23, 2005, the shift operators put the rectification column , the so-called raffinate separation tower, back into operation after a four-week maintenance shutdown . First, the shift workers filled the column with liquid hydrocarbons without starting the heater or withdrawing liquid from the column. The normal liquid level in the rectification column was 2 meters.

At around 3 a.m., an employee acknowledged the first high level alarm, which responded at a level of 72%, corresponding to a level of 3 meters. Another high alarm at 78%, corresponding to a level of about 3.25 meters, did not respond because the instrument was defective.

When the operators interrupted start-up around 5:00 a.m., the level in the column was around 4 meters. After the maximum permitted fill level was exceeded, the fill level could no longer be read because the instrument did not display it. Due to a defect, the second level instrument even indicated that the level in the column was falling.

10:00 a.m

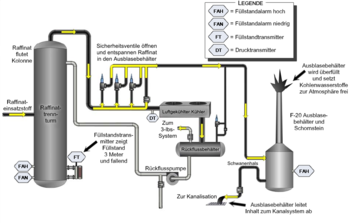

At 9:50 a.m., the operators resumed start-up operations and conveyed more raw material into the raffinate separation tower. At 10 o'clock they started the heater. At 12:40 p.m. the level was already 42 meters, although the level indicator showed 3 meters with a downward trend. The high level triggered a high pressure alarm. As a countermeasure, the operators shut down two burners in the heater to lower the temperature and thus the pressure. They also opened a manual valve to the blowout canister, which was open to the atmosphere.

13:00 'O clock

At 1:00 p.m. the shift opened the way to the storage tanks . The raw material was heated by about 65 ° C. via the heat exchanger , which resulted in overheating in the rectification column. At 13:05, the hydrocarbons began to boil in the column, at 13:10 the column was overfilled and flooded a pipeline that led to safety valves 47 meters below. The safety valves opened at 1:14 p.m. , however, as the hydrocarbons began to boil in the column, the pressure rose from 1.5 bar to around 4.5 bar. The hydrocarbons ran into the blow-out tank, from where they partially went into the sewer system . At around 1:09 p.m., the entire blow-out container was filled, and a level alarm in this container did not work either.

explosion

The container flooded from the 34-meter-high chimney for about a minute. About 28,000 liters of volatile hydrocarbons were ejected from the chimney in a geyser-like manner . The released volatile liquid evaporated, forming a flammable vapor cloud. The BP employees noticed the hydrocarbon cloud and called over the factory radio to stop all hot work and to switch off all potential ignition sources . However, the hydrocarbon cloud ignited at 1:20 p.m. on a pickup truck that was idling about 8 meters away .

The force of the explosion killed 15 contractor employees who were holding a meeting in construction containers about 45 meters from the explosion site and were hit by the shock wave of the explosion. There were eleven employees from Jakobs Merit who were working on a maintenance shutdown of the ultracracker system , as well as four employees from the Fluor Corporation .

The chief medical examiner of Galveston County , Stephen Pustilnik, gave the cause of death in the medical reports skull, brain - as well as other traumas to, caused by blunt trauma flying around debris. The fire was under control after about an hour and completely extinguished after two hours.

Investigation reports

Internal BP experts as well as various authorities and commissions examined the explosion from a technical point of view and under aspects of organization and safety culture . An in-house team of experts recorded the results of the technical investigation in the so-called “Mogford Report”, and the results of the investigation with regard to the organizational aspects and the responsibility of management in the so-called “Bonse Report”. The US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board examined both the technical aspects and the responsibilities of the regulatory authorities. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) subsequently checked compliance with the various requirements in the refinery.

Mogford report

A team of experts led by John Mogford, Senior Group Vice President Safety and Operations, examined the technical aspects of the explosion and suggested corrective actions. On December 9, 2005, BP published this accident investigation report. The report identified four critical factors as the main causes, without which the incident would not have happened or would have had a significantly smaller impact. This included the unintentional release of substances, the operating instructions and their compliance with the commissioning of the rectification column, the work control as well as the construction of the construction container and the design of the blow-out container.

Bonse report

Another internal report, the so-called Bonse Report, which was prepared under the direction of the Chairman of the Supervisory Board of BP Germany, Wilhelm Bonse-Geuking , made numerous management errors responsible for the refinery explosion. On May 3, 2007, a court ordered the publication of the report, which was actually only drawn up for internal purposes. The report measured the responsibilities of management based on internal management instructions (BP Management Framework, BPMF) and the BP Code of Conduct. The refinery organization defined these responsibilities based on the group-wide regulations in a so-called Blue Book , which was published in 2005. In addition to personal misconduct, the report identified unclear corporate responsibilities at all levels from the plant team to the Texas City refinery organization to the entire refining segment of the group as contributing factors to the incident. As a further contributing factor, the report denounced the poor condition of the systems and the insufficient expenditure on maintenance. Although they were not deferred at all levels of the group, too few resources had been made available for them.

The report identified the safety culture in the refinery, a high willingness to take risks and the absence or non-compliance with clear operating instructions as the main factors . The accident management officer took over his office in January 2005, but was not considered sufficiently trained for his task. In addition, those responsible did not learn any lessons from past mistakes. In the year 2000 alone there were 80 accidental releases of hydrocarbons ; the management had not consistently implemented appropriate improvement measures.

There was a lack of clear structures, and this meant that the operators started up the system without the necessary communication with other departments and systems. The responsible shift supervisors came too late for work or left too early, and insufficiently trained operators started the system. Alarms that signaled overfilling of the rectification column were interpreted incorrectly. The report accused the refinery manager of the fact that the focus of his actions was on occupational safety and not on plant safety.

US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board accident investigation

Given the importance of the disaster, the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board examined both the safety management of the Texas City refinery and the role of the BP Group and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) as regulatory agencies . The authority presented the results of the investigation in a more than three hundred-page report on March 20, 2007.

The CSB found that organizational and safety-related deficiencies at all organizational levels of BP contributed to the refinery explosion, for example through cost reductions and spending cuts in the safety-related area, although a large part of the refinery infrastructure and the process facilities were in poor condition. In addition, those responsible had cut the budget for the training courses and cut staff .

The CSB also noted that OSHA, as the regulatory authority, had failed to conduct scheduled inspections of the refinery and enforce safety regulations, even though there were many warning signs. After the explosion, OSHA found 301 violations of regulations and imposed a fine of 21 million USD. The CSB found that only a limited number of OSHA inspectors had the technical training and experience necessary to carry out the complex investigations in refineries.

The CSB made a recommendation for the development of a guideline for understanding, recognizing and dealing with states of exhaustion during shift work . The subsequently developed guideline API Recommended Practice 755 recommended the creation of guidelines for dealing with fatigue syndromes (Fatigue Risk Management System, FRMS) for refineries, petrochemical and chemical plants and similar facilities. These guidelines contain recommendations for working on rotating shifts, such as the number of overtime hours and the number of days on which you should work without interruption.

The CSB report also found that BP and Amoco had failed to observe and implement safety recommendations, some of which were given long before the explosion. In 1991, for example, the Amoco planning department suggested replacing the atmospheric blow-out containers with flare systems. Various departments renewed these proposals, most recently in 2002. However, the necessary budget was not made available. Between 1994 and 2004 there were eight cases in which hydrocarbon vapors were released into the atmosphere through a blowout container. In an in-house process safety standard, Amoco banned the construction of new blow-out containers in refineries. Nevertheless, in 1997, Amoco replaced the affected blow-out container, which came from the 1950s, with a container of the same construction. As a result of the accident, BP pledged to eliminate all blowout containers in the vicinity of flammable hydrocarbons. Due to the amount of flammable hydrocarbons released in a short time, however, it is sometimes doubted that a flare system would have prevented the explosion.

Following an accident in 1995 at a Pennzoil refinery in which an explosion of two storage tanks killed five workers housed in construction containers, there was a recommendation for the location of construction containers. BP ignored the recommendation, assuming that the risk was low because the containers were empty most of the time.

Legal action

The explosion led to a number of lawsuits and lawsuits in both private and environmental law. Initially, two workers injured in the blast filed a lawsuit against the BP Amoco Chemical Company of Delaware, JE Merit, a subsidiary of Johnson Engineering, and the refinery director. Those affected filed a total of 3,000 lawsuits, in 1,350 cases a settlement was reached after a short time. BP set aside $ 1.6 billion for compensation payments. BP was also charged with violating environmental laws and OSHA imposed large fines.

Civil actions

In the aftermath of the explosion, many of those affected filed civil lawsuits against BP. According to various sources, BP paid over $ 1 billion to plaintiffs as a settlement. The Eva Rowe case caused a stir.

The young woman lost her parents in the explosion, who worked as subcontractors for JE Merit. It spread that she would not accept any money and hold the company accountable. Ed Bradley , a well-known American journalist , made her story nationally known on the television magazine 60 Minutes .

On November 9, 2006, BP reached a settlement with Rowe as the final plaintiff after Rowe's attorneys tried to summon John Browne as a witness. The severance payment for Eva Rowe remained unknown. As part of the settlement, BP paid $ 32 million to colleges and hospitals named by Rowe, including the Mary Kay O'Connor Process Safety Center at Texas A&M University , the University of Texas Medical School at Galveston , the Truman G. Blocker Adult Burn Unit and the College of the Mainland in Texas City . BP also published around seven million pages of internal documents, including the Telos and Bonse reports.

Violations of environmental and occupational safety laws

On the initiative of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (Texas Commission on Environmental Quality; TCEQ) opened the Attorney General of Texas (Texas Attorney General) proceedings against BP Products North America Inc. for violations of the laws on air pollution control (Texas Clean Air Act), the labor laws (Texas Health & Safety code) and water protection laws (Texas water code) in connection with the explosion.

In an agreement, BP agreed to pay a $ 50 million fine. This included litigation costs of $ 500,000. In addition, the court and BP agreed to a three-year suspended sentence, during which BP undertook to support investigations into the circumstances of the accident initiated by government agencies. Another probation requirement was compliance with all orders issued by OSHA and TCEQ. In return, the Justice Department pledged not to allow additional criminal charges against BP in connection with the refinery explosion.

Baker report on safety

In October 2005, on the recommendation of the US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigations Board (CSB) , John Browne, then CEO of BP, convened an eleven-member commission headed by former US Secretary of State James A. Baker . The Commission should investigate security management across the Group and develop recommendations for improving security. The committee interviewed over 700 BP employees at all organizational levels during on-site visits at the five BP refineries. Employees and technical advisors were interviewed about the safety culture and process safety records were reviewed. The panel also held public meetings in the communities of the refinery sites and interviewed other companies about process safety management. The results of the investigation were presented in a comprehensive report on July 16, 2007.

The commission subdivided the findings of its investigation into the three sections safety culture of the company, process safety management including the evaluation of the performance of the management system and corrective measures as well as supervision in the company. In the report, the commission identified some significant deficits in the safety management of the refineries. It was also found that BP had not differentiated between occupational health and safety , environmental protection and plant safety and that good accident statistics were an indicator of high plant safety. The panel called on BP to give process safety the same priority as occupational safety.

Recommendations of the Baker Commission

As a result of its investigations, the commission recommended a total of ten measures to improve process reliability. At the same time, the Baker Commission transferred the results of the investigation to other industrial sectors.

“While the panel made no findings about companies other than BP, the panel is under no illusion that the deficiencies in process safety culture, management, or corporate oversight identified in the panel's report are limited to BP. If other refining and chemical companies understand the Panel's recommendations and related commentary and apply them to their own safety cultures, process safety management systems, and corporate oversight mechanisms, the Panel sincerely believes that the safety of the world's refineries, chemical plants, and other process facilities will be improved and lives will be saved. "

“While the panel has no knowledge of any company other than BP, we do not succumb to the illusion that the inadequacies in process safety culture, management and oversight within the company identified in the panel's report are limited to BP. When other refining and chemical companies understand the panel's recommendations and related comments, and apply them to their own safety culture, process safety management systems, and corporate control mechanisms, the panel sincerely believes that safety is improving in refineries, chemicals and other process plants around the world and life can be saved. "

The first recommendation concerned the responsibility of top management for process safety. The management and the board of directors should create effective management tools and structures and define suitable goals for process security in the company. Through their commitment, instructions and actions, the top management level should acknowledge the importance of process security in front of the workforce. The committee also recommended the establishment of an integrated and comprehensive process safety management system that systematically and continuously identifies, reduces and manages risks.

Thirdly, BP should introduce a system that ensures that employees at all organizational levels in the group are given adequate knowledge of process security. BP was also asked to develop and maintain a trusting and open safety culture in the individual refinery locations. Another recommendation concerned the definition of clear responsibilities and goals at all organizational levels, combined with clear reporting and accountability requirements. The sixth recommendation concerned the support of direct line managers in refineries in the area of process safety.

The commission also recommended the definition of indicative and to be followed metrics for process safety. The eighth recommendation related to the definition and implementation of a system for functional testing of process safety. The introduction and implementation of the recommendations should take place at the board level. The sum of the recommendations should make BP a leading company in the field of process safety and lead to its improvement in all refineries in the long term.

Record fine after further incidents

After the explosion in the isomerization plant, other safety-related incidents occurred in the refinery. On July 28, 2005, a crack in a heat exchanger in a desulfurization plant released hydrogen gas . The subsequent oxyhydrogen explosion slightly injured one person and caused property damage of USD 30 million. The CSB investigated the incident and found the cause to be that a subcontractor had used elbows made of low-alloy steel during repair work . These pipe sections failed mechanically during operation due to hydrogen embrittlement .

Two weeks later, another incident occurred in a desulphurisation plant, which led to the neighbors of the refinery prompted had to leave their homes and shelters seek. In the following years other incidents occurred, some with fatal consequences. On January 14, 2008, an employee died of head injuries during maintenance work on the ultracracker system .

In 2009, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration conducted a six-month audit to evaluate the improvement measures taken by BP as an obligation arising from the refinery explosion. OSHA found 270 violations of existing requirements, 439 new violations, and imposed a US $ 87.43 million administrative fine on BP Products North America Inc., the highest in the agency's history.

In 2012, BP sold the Texas City refinery and parts of the distribution and logistics network to the US company Marathon Petroleum for USD 2.5 billion. According to BP, the proceeds will be used to pay compensation for the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico.

Global impact on safety culture

The publication of the Baker report and the internal and external investigation reports prompted numerous companies and government agencies around the world to rethink the position of plant safety and safety culture. The Texas City working group of the Plant Safety Commission at the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety issued recommendations for the further development of safety culture as a lesson from the refinery explosion.

The European Chemical Industry Association CEFIC recommended that its members pay greater attention to the area of process safety. The English Chemical Industries Association visited its member companies and asked members of the board of directors and supervisory board whether they had read the Baker report and would implement the recommendations.

As a result of the explosion, not only BP but also many other companies invested in improving process safety. Companies checked the work organization and changed, for example, the rules for setting up construction containers in endangered areas, regardless of their useful life. The explosion was the main impetus for the high investments in plant construction in the years after the disaster.

literature

- Trevor A. Kletz: What Went Wrong: Case Histories of Process Plant Disasters and How They Could Have Been Avoided , 5th edition, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford 2009, ISBN 1-85617-531-6 .

- Andrew Hopkins: Failure to Learn the BP Texas City Refinery Disaster , CCH Australia, Sydney 2008, ISBN 1-921322-44-6 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Explosion in the BP refinery in Texas City, press release of the German BP. Retrieved April 4, 2013 .

- ^ A b Maryam Kalantarnia, Faisal Khan, Kelly Hawboldt: Modeling of BP Texas City refinery accident using dynamic risk assessment approach. In: Process Safety and Environmental Protection , 88.3 (2010): pp. 191-199.

- ↑ Texas: Explosion in oil refinery kills many people. Retrieved July 4, 2013 .

- ^ Body pulled from rubble of BP's Texas City refinery. Retrieved July 4, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board, Investigation Report, Report No. 2005-04-I-TX, Refinery Explosion and Fire. (PDF; 3.4 MB) (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on July 29, 2013 ; Retrieved July 4, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c Baker Panel Report, p. 82. (PDF; 2.4 MB) Retrieved on July 4, 2013 .

- ↑ Severe explosions in an oil refinery. Retrieved July 4, 2013 .

- ^ Telos Perspective and Recommendations. (PDF; 1.1 MB) (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on December 27, 2013 ; Retrieved July 4, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ US Chemical Safety Board Concludes "Organizational and Safety Deficiencies at All Levels of the BP Corporation" Caused March 2005 Texas City Disaster That Killed 15, Injured 180. Retrieved July 4, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g M. Broadribb: Lessons from Texas City-A case history. In: Loss Prevention Bulletin. Institution of Chemical Engineers 192 (2006): 3. (PDF) (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on June 4, 2013 ; Retrieved July 4, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Flow diagram of the UOP Penex process. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on July 5, 2013 ; Retrieved July 4, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ EL Pollitzer: Platinum Catalysts in Lead-free Gasoline Production , in: Platinum Metals Rev. , 1972, 16, (2), pp. 42-47 ( PDF ).

- ↑ a b c d e T. Price: The Texas City Oil Refinery Disaster, in: Popular Mechanics, July 2005. Retrieved July 4, 2013 .

- ↑ a b Mark Kaszniak, Donald Holmstrom: Trailer siting issues: BP Texas City. In: Journal of Hazardous Materials. 159, 2008, pp. 105-111, doi: 10.1016 / j.jhazmat.2008.01.039 .

- ↑ Don Holmstrom, Francisco Altamirano, Johnnie Banks, Giby Joseph, Mark Kaszniak, Cheryl Mackenzie, Reepa Shroff, Hillary Cohen, Stephen Wallace: CSB investigation of the explosions and fire at the BP texas city refinery on March 23, 2005. In: Process Safety Progress. 25, 2006, pp. 345-349, doi: 10.1002 / prs.10158 .

- ^ A b Fatal Accident Investigation Report, Isomerization Unit Explosion, Final Report, Texas City, Texas, USA. (PDF; 1.7 MB) (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on January 18, 2016 ; accessed on March 21, 2015 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Safety deficiencies: Europe's largest oil company keeps making headlines with incidents. Retrieved July 4, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c BP study blames managers for 2005 blast at Texas refinery. Retrieved July 4, 2013 .

- ^ C. MacKenzie, D. Holmstrom, M. Kaszniak: Human Factors Analysis of the BP Texas City Refinery Explosion. In: Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. 51, 2007, pp. 1444-1448, doi: 10.1177 / 154193120705102015 .

- ↑ Noel D. Ryan, Huma Abassi: Fatigue Risk Management System - A Fit for Purpose Approach . In: 2012, SPE / APPEA International Conference on Health, Safety, and Environment in Oil and Gas Exploration and Production , Society of Petroleum Engineers (2012), ISBN 978-1-61399-211-1 .

- ↑ BP settles more claims from a Texas refinery fire - Business - International Herald Tribune. Retrieved July 10, 2013 .

- ^ Faisal I. Khan, Paul R. Amyotte: Modeling of BP Texas City refinery incident. In: Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries. 20, 2007, pp. 387-395, doi: 10.1016 / j.jlp.2007.04.037 .

- ^ BP Plant Blast Trial Jurors to Be Picked. Retrieved July 4, 2013 .

- ^ Robert L. Heath, Michael J. Palenchar: Strategic issues management: Organizations and public policy challenges. Sage Publications (2008) ISBN 1-4129-5210-7 .

- ^ Sönke Iwersen: BP refinery explosion in Texas City: A question of price. In: Handelsblatt. November 13, 2006, accessed July 4, 2013 .

- ↑ The Explosion At Texas City. Retrieved July 4, 2013 .

- ^ Terms of Settlement. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on August 12, 2013 ; Retrieved July 4, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ BP Products to Pay $ 50 Million for Illegal Emissions during Explosion, Fire at Texas City Refinery. Retrieved July 4, 2013 .

- ↑ Agreed Final Judgment. (PDF; 226 kB) (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on August 7, 2012 ; Retrieved July 4, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Baker Panel Report. (PDF; 2.4 MB) Retrieved July 4, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c Baker's 10 recommendations. Retrieved July 4, 2013 .

- ↑ a b CSB Issues Safety Bulletin on BP Texas City Major Fire: Better Material Identification Needed, Errors During Systems Maintenance Cited; Fire Caused $ 30 Million in Property Damage. Retrieved July 13, 2013 .

- ↑ BP America Refinery Ultra Cracker explosion. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on March 25, 2018 ; Retrieved July 9, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ US Department of Laboratories OSHA issues record-breaking fines to BP. Retrieved July 4, 2013 .

- ^ Steven Greenhouse: BP to Challenge Fine for Refinery Blast. In: New York Times. Retrieved July 4, 2013 .

- ↑ a b Oil company BP sells refinery. Retrieved July 13, 2013 .

- ↑ B. Knegtering, HJ Pasman: Safety of the process industries in the 21st century: A changing need of process safety management for a changing industry. In: Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries. 22, 2009, pp. 162-168, doi: 10.1016 / j.jlp.2008.11.005 .

- ↑ Recommendations of the KAS for a further development of the safety culture - teachings after Texas City 2005. (PDF; 164 kB) (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on June 29, 2016 ; Retrieved July 4, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Process safety leadership in the chemicals industry. (PDF; 220 kB) Accessed July 4, 2013 .

- ↑ Reminders of death linger 5 years after blast BP. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on August 3, 2014 ; Retrieved July 4, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Up and down with consequences. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on May 25, 2015 ; Retrieved July 4, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

Web links

- Sloppiness and deaths: The BP inferno , at SPIEGEL.de

- US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board, Investigation Report, Report No. 2005-04-I-TX, Refinery Explosion and Fire (PDF; 3.4 MB), official accident investigation report, at csb.gov

- Fatal Accident Investigation Report: Isomerization Unit Explosion, Final Report, Texas City, Texas, USA (PDF; 1.7 MB), BP internal accident investigation report, at BP.com

- Anatomy of a Disaster , 55-minute video of the course of the accident at csb.gov

Coordinates: 29 ° 22 ′ 29.5 ″ N , 94 ° 56 ′ 1.1 ″ W.