Reformation in Memmingen

The Reformation in Memmingen began in 1513 with the appointment of Christoph Schappeler at the Vöhlinschen Prädikatur in St. Martin in Memmingen and lasted until the 1563rd For the first eleven years, the Reformation was popularly promoted. During the Peasants' War , the city was occupied by the Swabian Federation and returned to Catholicism. Then the council pushed through the Reformation again. Initially oriented towards Zwingli's doctrine , the city confessed to Luther's Protestantism only late .

Life before the Reformation

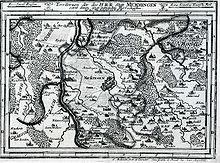

Memmingen had about 5000 inhabitants at the end of the 15th century and was therefore about the same size as Freiburg im Breisgau . Many localities, villages and hamlets in the area belonged to the city, the Unterhospitalstiftung or Memmingen patricians. The patricians and the guilds decided together with the large and small councils about the fate of the free imperial city. The patricians usually had great wealth and had enough time to take care of urban matters. Most of the time, one of them was the treasurer and mayor. The city had significant influence on the Swabian Confederation and was almost always represented in the Federal Council. It was the third strongest force in the federal government after Ulm and Augsburg .

Economic situation

The economic situation at the end of the 15th and beginning of the 16th century was difficult in all of Upper Swabia. The export- oriented economy of Memmingen was hit particularly hard by the recession that began at the beginning of the 16th century . In 1450 13 taxpayers could still be described as rich, in 1530 there were only six. The number of have- nots rose in the same period from 731 to 1206. It was even more gloomy among the weavers : in 1450 five had considerable wealth, in 1530 none. It was precisely this profession, which made up the majority of the craftsmen in Memmingen, that the recession hit particularly hard. Weavers' revolts were feared in the imperial city , as happened in Ulm in 1516. The fortunes were in the hands of a few and the majority of the urban population were poor. In addition, the city council strictly regulated the lives of ordinary people. All areas of public and private life were regulated. For example, only those who had a value of at least 50 guilders in fixed or movable property or in cash were allowed to marry. If someone had less, they were issued a poverty certificate and thus prohibited from marrying. Also, only a limited number of guests could be invited to weddings.

State of the Church

As in the rest of the empire, the church was in a desolate spiritual condition. Around 1500 there were 5,000 inhabitants compared to 130 clergymen, including 52 secular clergy, 28 friars and 50 nuns, but only a few of them were employed in pastoral care . During this time the population returned to a deep piety. Most of the time they obeyed the rules imposed on them by the Church. All of life was steeped in religion . However, the people felt that they were badly looked after by the clergy. Pastoral care and charitable tasks suffered massively, as many of the clergy did not or only poorly fulfill their duties. For example, the beneficiaries delegated the holding of masses to poorly trained clergymen, who did not celebrate them at the scheduled time but on other days. Even before the Reformation, the city council often intervened in church matters. Disputes between the city council and the monasteries, especially the Augustinian monastery and the Antonian monastery, reinforced this trend. Nevertheless, the citizens donated more masses from 1470 to 1521 than in the entire period before.

Predicature

A new means of securing salvation was the predicature . On the Friday after Maria Magdalena (July 22nd) 1479, the Vöhlins donated a preaching at St. Martin's Church. The owner of the predicature should read at least two masses a week. Further masses had to be read on Sundays and on 21 designated public holidays. The owner also had to have a master's degree . However, the positions of preaching were also in competition with the normal pastors' positions at the church, so that there were disputes here too. The preachers, who mostly saw themselves in a position above the preachers, were usually better theologically trained than the actual pastors. They saw their influence on the population at risk. In Memmingen, where the main pastor's position in the parish church of St. Martin was occupied by the nearby Antonite monastery - the church was incorporated into the monastery - there were additional tensions. The preceptor of the monastery was repeatedly accused of incompetence, as he was rarely in the city and neglected his pastoral activities. The first owner of Vöhlin's predicature, Dr. Jodokus Gay quarreled early on with the city council and the Antonite monastery. He is considered a pioneer for the reformer Dr. Christoph Schappeler .

Since the Middle Ages, the population has repeatedly had an influence on church life within the walls of the city. The two large parish churches of St. Martin and Our Women were not built by the respective monasteries in which they were incorporated, but by the citizens. The mayor's oath also took place on the day of the oath in St. Martin. Dr. Jodokus Gay wanted to change this and therefore wrote to the bishop of Augsburg in 1507 . Bishop Heinrich IV of Lichtenau , however, was undecided and submitted a supplication to the emperor. However, Gay threatened the papal ban and interdict . Emperor Maximilian I then ordered Gay to refrain from his demands. This dispute dragged on until the death of Gays in 1512. The city also repeatedly got into disputes with his successor.

The Reformation took place during this period. For many believers, the celebration of mass was an incomprehensible holy spectacle , which the believer watched passively, or a mysterious event. The incomprehensible Latin liturgical language did the rest. Another current also wanted to gain influence on church affairs.

The Reformation as a popular movement

In 1513, the vöhlin predicature stopped the preacher Christoph Schappeler. Born in the free imperial city of St. Gallen and who immigrated to Memmingen, the city council noticed as early as 1516 when he preached against the city's rich. An entry in the council minutes of August 21, 1521 can be linked to the Reformation:

- 14 days ago the preacher to sant Martin gave a violent sermon on the streets, for no good reason, so the rich are not like the poor, if they are from the burgers, with the appendix that he wants to command the community . That would like to lead to an awakening, dauon is vil vnd sometimes talked about, and invented, which he said about the war, then we won't punish. But he shouldn't bother about it: he wölltz dergemaind. But if he is otherwise an inheritance and allain aus aim encouraged speeches ettwan would be too heated, it will not be a good thing and Zangmeister, Strigel and the people who talk to me ain a friendly talk and ask ain in accordance with no attention advice to instruct.

This sermon must have been characteristic of Schappeler. After all, he took a socially critical and political-theoretical position. Rich and poor were not accorded the same rights in the imperial city. He concluded from this that the community should definitely defend itself against the council. The council, evidently embarrassed by the allegations, sent a delegation to Schappeler to reprimand him. It was important for the city council to show who was ruling the city. However, these council minutes also show that the city council was not yet aware of the explosive nature of Schappeler's sermons. He also had to act cautiously, as Schappeler already had a lot of support from the population and knew wide circles behind him. Parts of the city council must also have stood on Schappeler's side and taken his side.

A year after the entry in the council minutes, Schappeler became clearer as a theologian. So he preached that out of 1000 masses there was hardly one useful and that the clergy were all incapable of holding their office. Likewise, he denied the clergy any theological knowledge. Church rights and papal decrees are all secular in nature, so they don't have to be followed. This found open ears among the citizens of Memmingen, who were getting poorer and poorer, so that the call for religious renewal also became louder in the lower classes of the population. The aristocratic part of the city population, however, fought massively for the preservation of the old faith.

In August 1519 Schappeler had already written a letter to Joachim von Watt in which he expressed great sympathy for Martin Luther. In this letter he also reported on the disputation with Johannes Eck . The extent to which his sermons deviated from Roman Catholic teaching at that time can no longer be determined. As early as April 1522, the pastor of the Frauenkirche complained to the city council that the foundations had collapsed massively. However, the Council rejected this action on the grounds that it was not owed anything. Only the town clerk Ludwig Vogelmann recognized the danger in Schappeler's sermons and wrote to the patrician Ehinger in Rome in March 1522:

- Lutter in our land ain should I screamed and especially under his monks ... which amazes me that our hailiger father Pope and Cadinales soolich have to see and suffer things for so long, which is why it is important to watch out that ettwan will even preach.

In September 1522 he wrote in the minutes of the council:

- Half of Lutter was shouted here among the priests; preach against one another ... The preacher wants to ride there; to suspect that he fears the pischoff (and is not allowed to preach the warhait) ... So it does not happen to others either between the gaistischen

Shortly afterwards, the Augsburg Bishop Christoph von Stadion called on the city to comply with the imperial mandate and to take action against the Lutherans. Schappeler, who saw the air getting thinner and thinner, wanted to go back to Zurich with a recommendation from Joachim von Watt. Also Ulrich Zwingli made an effort for a free Schappeler preacher in Winterthur obtain and sent him the end of January 1523 Zurich represented articles. However, the City Council of Memmingen asked Schappeler to stay. The Council's attitude during this period was contradicting itself. On the one hand, he attached great importance to the continued presence of Schappeler, on the other hand, he urged the citizens to venerate saints. At the same time, he turned down a motion to ban the sale of Luther's writings. Ludwig Vogelmann was so outraged by the result of the vote that he wrote Der theufel Schlag darein underneath.

The first pictures were desecrated in early 1523. Two young people, Ulrich Geßler and Raphael Sättelin, stole the sculpture of a Jew from the Mount of Olives in the Frauenkirche. With this they went through the streets, mocked and mocked them. The city council punished the two patrician sons on February 9th. It can no longer be clarified whether the robbery was out of Reformation zeal or hatred of the Jews, or whether a dispute with the pastor was the trigger. It is only certain that this was the first documented action against portraits in a Memmingen church.

In 1523 the chronicler Galle Greiter reported a sermon:

- ... the Sunday after Martine, that Doctor Christoff Schappeler the first sermon Lueterisch ...

With this, Schappeler finally broke with the old teaching and the old church.

Because of this sermon, the city council had to intervene if it did not want to incur the emperor's disfavor. Nevertheless, Schappeler was only reprimanded again. On July 30, 1523, some citizens forced Pastor Megerich from the Frauenkirche on the open street to receive a complaint. In it the pastor's life and actions were reprimanded. This document reached the city council via detours and summoned the messengers. Among them was Sebastian Lotzer , who later often intervened in the Reformation events . The council reprimanded the people extremely severely and sharply. The rebuke of the council also says: ... but let everyone believe and do what they are responsible for against God and the world ... One of the reasons for this violent reprimand may have been the fear of unrest. In September the situation worsened, so that the city council felt compelled to send a letter to all clergy in the city with the following warning:

the Ir and the preachers should avoid all and everything to the highest degree, to close conspirationes, appendices and differences at the layen against ain other, so that leychtlich great indignation and unbelievable filth might grow up

The city council did not succeed in convincing the preachers, especially Schappeler, to formulate their sermons more gently. The preacher of the Elsbethenkloster converted to Lutheran teaching. But he soon left the city out of fear. On January 20, 1524, the Augsburg bishop asked Schappeler to appear at his castle in Dillingen . There were large and violent arguments in the city council. Most of the members, however, supported Schappeler. In his reply to the bishop, he asked for safe conduct for Schappeler and for permission that two councilors could accompany him and also be present if he had to answer to the bishop. The bishop refused these requests. Schappeler then did not appear at the bishop's; then imposed this upon him in February to excommunication . The Reformation was no longer a pure Memmingen topic. Now the city leaders would actually have been forced to expel Schappeler from the city and forbid him to preach. This led to major wing battles in the council. The old-believing mayor Conrater and the fanatically old-believing town clerk Ludwig Vogelmann had to leave the meeting several times. The council decided not to expel Schappeler from the city, and he was also allowed to continue to work as a preacher at St. Martin and the Augustinian convent . This was the first time that the Council had taken a clear position in favor of the Reformation. Many council members already followed the new teaching.

In a letter sent to the emperor a short time later, it says:

- ..but on the other hand don't let us preach the haylig euangelium loudly and rain .... by the measure like the same a long time ago, all lay misuse and lack should be ... Then we ... believe ... when the Crist believing for the sacrament of the night against the sy den body cristi that warhältig himel brott and his blood from the living word, and hatefulness through the enjoyment of faith and receiving ... but every and all about, in which and other ainen everyone is free to believe. ..

It appears from this letter that the council's naive opinion was that one was only advocating the pure gospel cause and that the emperor could hardly blame them for that. The mass will be changed, the sacrament of the Lord's Supper will be celebrated in both forms . Otherwise no changes have been made. No altars or pictures were removed from the churches. The hospital master was also allowed to hold the indulgence ceremony in 1524, as he found it good. So the council tried to keep everything that was not directly related to theology as it was and to keep up appearances. This was an attempt to appease the emperor and bishop. With the excuse that one would only let the pure gospel preach, one turned to Zwingli's teaching. The council tried with the changes made to prevent a riot in the city. So he did not actually carry out a Reformation, but acted as the citizens of the city liked and included them. On April 15, 1524, the town clerk Ludwig Vogelmann resigned from his office, which he had held since 1508 because he could not support the Reformation. When the new mayor was elected in 1524, Hans Keller took over from the old-believing mayor Ludwig Conrater. Keller was a friend of the Reformation, but not hasty and averse to rushing things. After Vogelmann's resignation, the two most influential offices had fallen to the new believers. The new town clerk Georg Maurer stayed there until 1548. In May 1524, the Reformation also affected the town's monasteries. Some of the nuns of the Elsbethenkloster indicated that they no longer wanted to stay in the monastery, but wanted to get married. Such efforts also arose in the Augustinian monastery , which is why the council asked at the city council in Ulm whether it could inventory and keep the monastery property. This was approved. Whether the council wanted to get hold of the monastery property quickly or whether it feared that the former nuns and monastery brothers would steal the church treasures is not clear from the sources.

Up to this point the Reformation had been peaceful, apart from minor disputes. When the protest letter was handed over to Pastor Mergerich, there was already strong sympathy among the laypeople. They were asked to do this by Schappeler and his lay assistant Sebastian Lotzer, who both - Schappeler in sermons, Lotzer in writings - asked the citizens to spend their free time studying the Bible. 1523 Scripture appeared from Lotzer Ain Christian send letter is angetzaigt is dz the Malays makes vnd be right, speak of the word hailigen gots learning, vn write ... . The demand to only accept what can be justified from the Bible contained a lot of political explosives. In July 1524, a group of citizens declared that they no longer wanted to pay church tithing because the Bible did not provide for this. Since the urban villages and foundations were also obliged to pay the tithe, this time the city council could not ignore it, but had to act if it did not want to forego the income from the tithe. The farmers of the village of Steinheim refused to pay the large and small tithes to the pastor and the municipal sub-hospital foundation. The city council had this problem discussed at the Swabian City Council in Ulm. He then announced that everyone was required to pay tithing if they did not want to face severe penalties. When only the master baker Hans Heltzlin refused to pay the tithe, he was arrested. The population reacted by gathering a larger crowd and forming a committee organized according to guilds. Ambrosius Baesch was elected as spokesman. He protested to the council against its actions and, on behalf of the population, demanded the immediate release of the master baker and an assurance that no one would be imprisoned for refusing to tithe in future. Furthermore, the council was asked not to interfere in questions of church taxes, anniversaries, sea equipment and other matters. But he should ensure that only the word of God is preached in the churches. He should also take action against those clergymen who preached against Schappeler. Under pressure from the population, the council had to release the master baker again. The city council had to negotiate the other points with the Elfern and the community. As a result of this defeat, the council was forced to no longer make important decisions on its own, but in cooperation with the municipality. The power of the council was broken.

In the days that followed, the clergy were placed under municipal jurisdiction and their duties and rights, including tax obligations, were placed on an equal footing with the citizens. The threat was also voiced, where sy in the ainung with praise that one then said in the screen . Schappeler requested that the Lord's Supper in St. Martin be distributed in both forms according to the new teaching, as well as abolishing the hour prayers and the ministries of the soul. The council replied evasively. He stood between different fronts, on the one hand the church and the emperor who wanted to keep the old doctrine, on the other the population who wanted to introduce the new doctrine. Due to the weakening in the dispute over the master baker Hans Heltzlin, the council was condemned to immobility. A new Lord's Supper and baptismal ordinance could emerge without any details being written down. Schappeler, who has become a celebrity in the immediate vicinity and further afield, continued to preach to St. Martin and in the church of the Elsbethenkloster. The influx of believers to his sermons was so great that the city council felt compelled to reinforce the gate guards with two guild masters each. Furthermore, hall guards were sent to the churches to maintain order.

Within the city, pressure increased on the council to carry out church reforms. New believers repeatedly asked for the Reformation to be introduced at the Frauenkirche as well. The pastor Mergerich there, however, stood by the old faith and did not allow this. The population also threatened to forcibly remove him as pastor. Mergerich and Schappeler now fought each other all the more violently in the sermons. The council tried to mediate in the dispute, but to no avail. The council then asked Mergerich and the hospital master of the Kreuzherrenkloster whether Mergerich could take part in a disputation. Both replied that this was not possible without the knowledge and will of their authorities. However, if the Council took responsibility, they would face this dispute. The city council refused, so the disputation did not take place. The population now really pushed for new teaching. During the Christmas service on December 25, 1524, there was a commotion in the Frauenkirche. Pastor Mergerich was kicked and beaten with fists and feet and driven into the sacristy, as he wrote to the Bishop of Augsburg. Only the summoned council members could settle the dispute. Mergerich had to promise to take part in a disputation on January 2, 1525. Sebastian Lotzer, one of the leaders, apologized in a pamphlet as follows because of the outrage in the city and in the surrounding area that this tumult caused:

- Dan ain ersame gmaine desires nothing else dan wz götllch vn right, wa ain decent Oberkait ... according to the same deal / wyrt you are more differently vn obedient to the younger, whe the saying is not taken, you have to be more obedient than that people.

On the one hand, he rejected the accusation that the followers of the new doctrine wanted to take away the wealth of the rich, on the other hand, he defended the pure matters of faith. He also used the word Protestant for the first time . Most of the followers of the new doctrine must have been have-nots and poor citizens who wanted to return to an early Christian community of property. Lotzer admitted this in a pamphlet, even though he denied the use of force.

Reformation after the Memmingen disputation

The Memmingen disputation took place from January 2nd to 7th, 1525 in the Memmingen town hall . The old religious pastor Mergerich from the Frauenkirche and the reformer Schappeler from St. Martin faced each other. Other clergymen of old faith also took part in the disputation. Dr. Ulrich Wolfhart. Representatives from all twelve guilds were named as assessors. At the Memmingen disputation, Schappeler put up seven articles. With the previous decision to only accept arguments from the Bible, it was already clear that Mergerich would lose. Right from the start, the competence of the bishop, the pope and the councils in matters of faith was denied.

After Schappeler had won the disputation, the council was no longer able to give evasive answers to the pressing Protestant ethnic groups. Nothing stood in the way of the fundamental reorganization of the Memmingen church system. Still, the council was cautious in its actions. Before reforms were introduced, the Council did a lot of research. For example, the preacher Conrad Sam from Ulm had to prepare an expert report. The guild master Hans Schulthaiss was sent to Augsburg to meet with the preacher Dr. Urbanus Rhegius and the legal scholars Konrad Peutinger and Rehlinger . Only when they approved did the Memmingen church system begin to be reformed from the ground up. The clergy were allowed to marry and were given the same rights and duties as ordinary citizens. The spiritual jurisdiction was abolished and all disputes were brought before the secular courts. The clergy were accepted into guilds, they had to pay taxes and take the citizens' oath. However, they were left with all ecclesiastical income such as mass foundations and soul devices. Completed measurement pillars were not filled again. The Holy Mass was abolished, instead an altar service was held daily in both parish churches. The sacrament was given in both forms. The council recommended that citizens give church tithe , but forbade refusal to do lay tithe . The main church of the city, St. Martin , was incorporated into the Antonite monastery, but Schappeler actually directed the church. The council and the guilds jointly elected the pastors. The city hired Simprecht Schenck, a priest who had left the Buxheim monastery , as a preacher in January 1525. The old-believing pastor of the Frauenkirche, named Mergerich, was often summoned to the council and rebuked for diatribes.

The monasteries in the city reacted differently to the new situation. While the upper hospital was adjusting, many monks resigned from the convent of the Augustinian monastery . The Elsbethenkloster slowly dissolved. Only the Franciscan Sisters were not affected by the events in the city and carried on their convent in the usual way. Even after these reforms were introduced, the unrest in the city did not end. An assassination attempt by the Augsburg bishop on Schappeler failed.

End of the Reformation as a popular movement

During the Peasants' War , the Memming population supported the rebellious peasants. The farmers in the urban area submitted the Memmingen articles to the council . Due to the support of the population, the council had to give way and make various concessions to the farmers. The people of Memmingen were not only fond of the Memmingen farmers, but also the other rebellious farmers. The council had to ban the sale of weapons to the insurgents. This is how the Upper Swabian farmers met in Memmingen. They founded the Christian Association in the Kramer Guild and wrote the Twelve Articles and the Federal Order . Here, Sebastian Lotzer , who is considered to be the author of the scriptures, came to the fore. The scriptures are about reconciling secular law with scripture. Therefore, all duties that are not listed in the Bible should be abolished. Since the council no longer knew what else to do, the Swabian Federation was asked for help. The Swabian Federation was asked to hurry with 200 men to Memmingen to help the farmers and the rioting population. However, the Bund entered the city through the Ulmer Tor with 200 riders and 700 men . This gave the Swabian Federation the long-awaited opportunity to eradicate the new teaching in Memmingen. When they were greeted by the Grand Guild Master Hans Schulthaiss, the captains indicated that they had to take action against the leaders and the preachers and that this was also secured by the covenant estates. Numerous people were arrested and detained. Many were also executed. This is how Captains Diepold von Stein, Eitelhans Sigmund von Berg and Linhard von Gundelsheim wrote to the Bund:

- how purted on sunday next passed in Dreyen with the name maister Paulßen schulmaister, master Adam maurern and Hansen Lutzen ain Wirt let themselves be beheaded, and ligen ir Zwen still in fengnus, which we finished you days ago, so the pot of the paurn not were thrown down

The preacher Schappeler, together with many others, including Sebastian Lotzer, managed to escape from Memmingen. They found asylum in St. Gallen, Switzerland. The city was in great distress due to the insurgent peasants besieging the city. The Waldburg Truchsess freed the city from its grip on July 3rd. The pastor from Kaufbeur filed a lawsuit against the city with the Swabian Federation because it had violated the papal bull and the imperial mandates. They also allowed the sale of Lutheran scriptures and Lutheran sermons against the ban. Furthermore, the sacrament was administered in both forms at the instigation of the council. However, the Memmingers denied this on the grounds that they had only acted according to the Holy Scriptures. As a result, the lawsuit was not even taken up. Any citizen who could swear not to have participated in the uprising was not persecuted. At the request of the Antonite Preceptor, who had returned from his exile, the mass had to be reintroduced. This was what the newly elected councilors had to swear on July 9, 1525 to the captains delegated by the federal government. The evangelical preacher Simprecht Schenck had to be dismissed and expelled from the city. The monks who had left the monasteries also had to leave the city. The taxation of the clergy and the taking of the citizenship oath were abolished. Furthermore, the population should celebrate the anniversary. With these measures, the Swabian Federation set all reformatory measures back to zero. This ended the Reformation as a popular movement.

Reformation by the city council

After the Swabian Federation had reversed all the Reformations, religious life was initially back in Catholic hands. However, the population of Memmingen could not be counter-reformed by the federal government. So in October 1525 the council hired a Protestant preacher again. For a short time, Dr. Hans Wanner in the city. But since the council feared renewed interference by the Swabian League or even the emperor, Wanner was not hired as a preacher. Schappeler also wanted to return, but the council also refused. It was written to him that due to the events in July 1525 they no longer wanted him. The new preacher Georg Gugy was warned again and again that he should not preach anything that the old believing clerics could turn against him. The citizens of the city were advised to pay the church tithe. Eberhart Zangmeister was sent by the city to the Speyer Reichstag in 1526. He handed over a document about the spiritual complaints. However, the Reichstag could not bring itself to an agreement, which is why it decided on August 27, 1526 to wait until a council came. In the final paper it says:

- So live, rule, and maintain with their subjects, as everyone hopes and trusts to answer to God and Kayer's majesty

Because of this final paper, the Swabian Federation's request to dismiss the new preacher Georg Gugy was not followed. The proven preacher Sigmar Schenck was brought back. Also on the basis of this document, the Council took the Reformation into its own hands from now on. He asked the Augustinian prior to dismiss his cook. He now also proceeded more sharply against the so-called priestly whores. It was stipulated that all of these had to leave the city. The council also awarded the sermons to St. Martin , Our Women and the Elsbethenkloster, which had actually already been given to Old Believers . The Antonite Preceptor then appealed to the council. This was not granted, which is why the Preceptor left the city. Numerous conservative citizens, mostly from the big guild , also left the city and gave up their citizenship. Among them are respected citizens such as Hans Vöhlin and Hans Schulthaiss, who was repeatedly Federal Councilor and member of parliament and parliament. The council deeply regretted their decision, as a result of which it mostly lost high tax revenues. The old-believing Vöhlin preacher was forbidden to preach. The Augsburg bishop and the Swabian Federation then complained, but the council left unconcerned. On November 11, 1527, at a meeting with other cities of the Swabian Federation, it was decided that the Swabian Federation was not authorized to issue instructions on religious issues until a general council would take place. At the city conference in Ulm on September 29, 1527, Peutinger prevented a division into old and new believing cities. In November the council decided to obtain an opinion from Ambrosius Blarer from Constance. In the new breed regulations, which were read out from the pulpits of the Memmingen churches in January 1528, the Augsburg marriage judicature was excluded. Except for the holidays of Christmas, New Year, Easter, Ascension, Pentecost, Annunciation and Assumption, all other church holidays have been abolished. The order of worship was revised. The Lord's Supper was from now on a memorial meal. It had to be served in both forms at least four times a year. The baptisms were now also held in German. However, this was not carried out because the Zwinglische Schenck and the Lutheran Gugy could not agree. The main issue here was the question of the Lord's Supper, which is why the city sent these two to the Bern disputation in January 1528 . Without having reached an agreement there, they came back to town. Most Memmingers, however, were attached to Zwingli's simpler theological interpretation of the question of the Lord's Supper. In the meantime, the city began to gain ecclesiastical rule in the monasteries. The Augustinian Abbot had to recognize the council as patron and patron, the movable church property was inventoried. The first church foundations were removed from the church property and the equivalent was put in the general box. In the meantime consultations were started with other newly believing imperial cities on how best to behave. Joining the federal alliance was already being considered at this time. These deliberations were taken by the emperor as a threat, which the imperial cities immediately rejected in a letter. In March 1528, the council turned repeatedly to Blarer, so that he should come to the city to settle the disputes between the local preachers. Blarer didn't come to town until the beginning of November. However, he was unable to mediate in the sacrament controversy. The council now had to set the direction itself and dismissed the Lutheran Gugy and voted for the Zwinglean denomination. At the same time, the council abolished mass in the Memmingen city churches. This measure was decided on November 30, 1528 with a citizens' referendum. In a letter from the council to the guild masters it says:

- Sy listened to preaching on sunday ... and understood that the meß like sy bither held ain grewel in front of god and ain reading of the suffering and merit of cristi and that ain every Christian Oberkait by irer souls owed bliss the conqueror advice of opinion and will As long as you liked it and to the advice therefore always wave the sy with the help of the almighty let the priesthood remind you of this ...

On December 9th, the Eilfer assembly voted on the abolition. Of the 132 express volunteers, 104 were present, 90 of whom voted in favor of the council's motion. Only the guild members of the big guild had concerns. In the minutes of the Council of December 9th, 1528 it says:

- Hansen Kellers and others should have constant advice; worried, we don't have to rise; his more and less who have not done it .

The chasubles and other church implements were taken into safekeeping by the nurses. Next, the council set about reforming the city's monasteries. Two councilors were placed before the Augustinians as carers. They had to take an inventory and lock the valuables. One key each was given to the caretakers and the monks. The sisters of the Elsbethenkloster converted and left the monastery. On February 15, 1529, they handed over their entire monastery property to the Unterhospitalstiftung. In return, the resigned sisters were promised accommodation and food. The only monastery that resisted the Reformation was the Franciscan convent. A commission set up especially for this purpose, made up of the council, guild masters and blarers, was unsuccessful. The Augsburg bishop then protested against the actions of the council. Johannes Eck wrote a treatise for this. This was publicly refuted on January 15th by Ambrosius Blarer in the Martinskirche. Due to the abolition, the representative of Memmingen was excluded from the Bundestag . Furthermore, four letters of appeal were presented to him. The city should respond to this within four days. Only the cities of Augsburg , Konstanz and Ulm pledged their support to the city, which had to fear the federal execution. The fact that Strasbourg also abolished the mass on February 20, 1529, gained another supporter. At the Bundestag on March 3, 1529, only Esslingen demanded that the mass should be reintroduced, but the cities did not agree among themselves. So the problem, which affected several cities, was postponed to a later Bundestag. Meanwhile, the city dismissed the Lutheran preacher Gugy and banned him from preaching inside the city. In June 1529, a Memming justification, which was written by Blarer, was presented to the Federal Assembly meeting in Augsburg. However, the Reichstag did not go as the council wanted, which is why it expected an invasion by the Swabian League or the Duke of Bavaria . However, the council allowed the Lord's Supper to be served in both forms for Easter. About 200 people took part. Encouraged by the Reichstag, the Antonite Preceptor applied for permission to read Mass again, which the council rejected. Again there were quarrels between old and new believers. Then other people moved out of the city. The question of the Anabaptists existed, but unlike other cities, they were not persecuted or burned. The council merely banned them. On July 19, 1529, a meeting of the cities of Ulm, Biberach, Isny, Lindau and Kempten was held in Memmingen. The aim of this meeting was an alliance of these cities with a connection to Zurich and Bern via Constance. At the next meeting, which also took place in Memmingen from September 5th to 7th, such a decision was postponed to the next day of the city. After the Marburg Religious Discussion failed, another meeting was scheduled in Schmalkalden at the end of November. Here the delegates sent by the city (mayor, town clerk and patrician) refused to accept the Schwabach articles . After Ulm and Bernhard Besserer had distanced themselves from the Swiss alliance, Memmingen did the same. After most of the cities of Upper Germany decided to accept the Augsburg Confession , Memmingen, together with Strasbourg, Constance and Lindau, formed their own alliance, which was called the Confessio Tetrapolitana , the so-called four-city alliance . However, the council was concerned that the emperor would besiege the city. Therefore the council presented this alliance to the emergency workers for voting in the guilds. With the exception of the large guild , all guilds agreed to the alliance. The end of Swiss influence on the Memmingen Reformation began with the Augsburg Reichstag in 1530. Memmingen joined the Schmalkaldic League on February 3, 1531 . A short time later, the council was negotiating at the Memminger City Conference with preachers from Ulm, Lindau, Biberach, Isny, Reutlingen, Konstanz and Memmingen about the Schmalkaldic League. They unanimously declared themselves in favor of the freedom of ecclesiastical ceremonies not necessary for salvation and rejected any violent action against the Anabaptists. Memmingen tried to force an alliance between the Swiss cities and the Schmalkaldic Confederation through several resolutions with other Upper German cities at various meetings. When Zwingli died in 1531, however, this path was closed.

Completion of the Reformation

After the council was primarily concerned with foreign policy, it went to the overthrow of the Memmingen monasteries in 1531. The former town clerk Ludwig Vogelmann wrote several writings against the Memmingen council, which is why he was arrested, tortured and publicly beheaded on January 3, 1531 in the market square despite an imperial letter of safe conduct . With this measure the council eliminated the greatest advocate of the Memmingen Reformation. The city administered the property of the Antoniter Hospital since 1537 the Preceptor had left the city. Nor did she have the proceeds delivered to him. This was justified with a waste of money and the lack of nursing care. At the same time, the city also accessed the Upper Hospital . These two monasteries made the start due to the incorporation of the two parish churches. The Lords of the Cross were not allowed to accept novices without the consent of the council; This agreement was made with the members of the convent because here, as with the Antonite monastery, the prior was not in town. Similar conditions were imposed on the Augustinians. The Franciscan Sisters did not enter into a confrontation, but fled to Kaufbeuren with their belongings. As a result of these measures, the council now had all the reins in hand and dominated the spiritual as well as the worldly life. On July 1st, Johannes Oekolampad and Martin Bucer criticized the fact that idols were still hanging everywhere in the Memmingen churches . Memmingen was supposed to imitate Biberach here . On July 7th, the council set up a committee of eight members chaired by Eberhart Zangmeister. The committee decided that all portraits had to be removed from the churches. The council commissioned the weaver Felix Mair and the guild master Martin Gerung, who were to coordinate this work. The Memmingen parish churches of St. Martin and Unser Frauen were closed for the period when the images were removed. The portraits were mostly sold or given to the craftsmen as wages. The former donors received nothing in return and were also not allowed to receive the pictures, altars or sacred objects.

literature

- Wolfgang Schlenck: The imperial city of Memmingen and the Reformation (= special print from: Memminger Geschichtsblätter. Born in 1968). Verlag der Heimatpflege Memmingen, Memmingen 1969 (also dissertation, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, 1969).

- Barbara Kroemer: The introduction of the Reformation in Memmingen. About the importance of their social, economic and political factors. In: Memminger Geschichtsblätter. Born 1980, ISSN 0539-2896 , pp. 101-112.

- Peter Blickle : Memmingen - A center of the Reformation. In: Joachim Jahn (ed.): The history of the city of Memmingen. Volume 1: From the beginning to the end of the imperial city. Theiss, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-8062-1315-1 , pp. 351-418.

- Gudrun Litz: The Reformation image question in the Swabian imperial cities (= late Middle Ages and Reformation. NR Volume 35). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-16-149124-5 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 15.

- ^ Peter Blickle: Memmingen - A center of the Reformation. In: Joachim Jahn (ed.): The history of the city of Memmingen. Volume 1: From the beginning to the end of the imperial city. Theiss, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-8062-1315-1 , pp. 351-418, here p. 352, last paragraph.

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 32 / Vogelmann to Dr. Jodokus Ehinger from March 12, 1522, City Archives Memmingen Drawer. 341/4

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 32 / Memminger Council Protocol of September 10, 1522.

- ↑ Memmingen Council Protocol of June 26, 1523.

- ^ Gudrun Litz: The Reformation picture question in the Swabian imperial cities . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-16-149124-5 , p. 140 .

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 31.

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 34 / Memminger Council Protocol of August 3, 1523.

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 34 / Stadtarchiv Memmingen, drawer. 341/5, September 1523.

- ↑ Kroemer, p. 39 ff.

- ↑ Schlenck, pp. 36 + 37

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 39.

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 40 according to the Memmingen council minutes of July 22, 1524.

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 41 based on an entry in the council minutes of December 16, 1524.

- ^ Reformation in Memmingen. In: Martin Brecht, Hermann Ehmer: Südwestdeutsche Reformationsgeschichte - On the introduction of the Reformation in the Duchy of Württemberg 1534. Stuttgart 1984, p. 163.

- ↑ a b Schlenck, p. 42.

- ↑ Schlenck, pp. 42 + 43

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 50.

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 50, footnote 157: letter of June 13, 1525, cited above. after Zs. d. Historical Association for Swabia (ZHVS) Volume 9. 1882, p. 55f. (No. 482)

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 51.

- ^ Schlenck, p. 59.

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 64.

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 65.

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 68.

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 86.

- ↑ Schlenck, p. 91.

- ^ Litz, p. 147.