STS-109

| Mission emblem | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| Mission dates | |||

| Mission: | STS-109 | ||

| COSPAR-ID : | 2002-010A | ||

| Crew: | 7th | ||

| Begin: | March 1, 2002, 11:22:02 UTC | ||

| Starting place: | Kennedy Space Center , LC-39A | ||

| Number of EVA : | 5 | ||

| Landing: | March 12, 2002, 09:31:52 UTC | ||

| Landing place: | Kennedy Space Center, Lane 33 | ||

| Flight duration: | 10d 22h 11min 9s | ||

| Earth orbits: | 165 | ||

| Rotation time : | 95.3 min | ||

| Orbit inclination : | 28.5 ° | ||

| Apogee : | 578 km | ||

| Perigee : | 486 km | ||

| Covered track: | 6.2 million km | ||

| Payload: | Assembly table for HST , solar cells, NICMOS cooler, ACS camera | ||

| Team photo | |||

v. l. No. Michael Massimino, Richard Linnehan, Duane Carey, Scott Altman, Nancy Currie, John Grunsfeld, James Newman |

|||

| ◄ Before / After ► | |||

|

|||

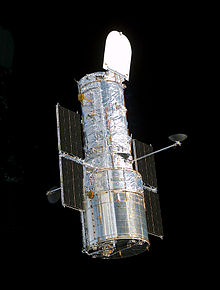

STS-109 ( english S pace T ransportation S ystem) is the mission designation for a flight of the US Space Shuttle Columbia (OV-102) NASA . The launch took place on March 1, 2002. It was the 108th space shuttle mission and the 27th and penultimate flight of the space shuttle Columbia.

The first space shuttle flight in 2002 was the fourth maintenance flight to the Hubble space telescope . In five outboard work (EVAs) some of the essential parts, such as the solar module and a control system are replaced. The telescope also received a new camera - the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS).

team

- Scott Altman (3rd space flight), commander

- Duane Carey (1st space flight), pilot

- John Grunsfeld (4th space flight), mission specialist

- Nancy Currie (4th Spaceflight), Mission Specialist

- James Newman (4th Spaceflight), Mission Specialist

- Richard Linnehan (3rd spaceflight), mission specialist

- Michael Massimino (1st spaceflight), mission specialist

Preparations

After her last mission, STS-93 , the Columbia was flown for her second general overhaul (Orbiter Major Down Period) to the manufacturing plant in Palmdale, California. Among other things, the outdated screens in the cockpit were replaced with new ones, making the Columbia the second orbiter with a so-called glass cockpit after the Atlantis . In mid-2001 she was flown back to the Kennedy Space Center and prepared for flight.

Due to one of Hubble's gyroscopes, which showed a slight malfunction and was therefore examined, the start date had already been postponed by several months at this time. Although the launch was scheduled for November 19, 2001, this problem has gradually postponed it to February 14, 2002.

The Columbia was driven from the Orbiter Processing Facility to the Vehicle Assembly Building on January 17, where it was attached to the external tank connected to the solid fuel rocket . Due to a problem with the crawler transporter that was supposed to bring the shuttle to launch facility 39A , the rollout there was delayed by several days and finally took place on January 28, 2002.

A few days later the crew arrived at the KSC for the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test . There they inspected the flight hardware and learned how to use the rescue systems at the launch system. The rescue systems are for the case that the team is forced to leave the launch system at the start. In the meantime, the start date had been postponed to February 28, 2002.

Mission history

begin

The last work on the shuttle was finished on February 22nd, 2002, so the countdown could begin on February 25th. The crew arrived at the Kennedy Space Center a few hours earlier. However, due to the relatively low temperatures at the launch site and a problem with the landing gear, it was decided to postpone the launch by one day to March 1, 2002 at 11:22 UTC . The filling of the external tank with liquid water and oxygen began on February 28 at around 19:00 UTC and ended at 22:13 UTC. In the meantime, the crew put on their take-off and landing suits , left the Operations and Checkout Building and arrived at the launch facility at around 1:00 a.m. UTC. After boarding the shuttle there was a small problem with an indicator that was supposed to show the hatch closing, which delayed the final closing of the hatch a little. Nevertheless, the Columbia took off as scheduled at the beginning of the 64-minute take-off window at 11:22:02 a.m. UTC. The solid rocket rockets were dropped two minutes after take-off. After eight and a half minutes, the main engines were switched off and ten seconds later the external tank was dropped.

After the start, it was found that one of the freon coolers on the shuttle was leaking fluid. After watching the cooler for a while, the crew could continue with normal duties. The cooler shouldn't cause any problems during the entire mission.

Rendezvous and capture

Starting with the first activation of the OMS engines , the OMS-2-Burn, the crew started a series of seven engine ignitions, which were carried out over the first three days of flight and brought Columbia to a position around 15 km behind Hubble. In this position, Hubble received the command from the control center in Greenbelt to stow the transmission antenna and to close the protective door of the inner mirror. A little later, the Columbia re-ignited its engines for the TI-Burn, the last main engine ignition before taking hold of the telescope, which further reduced the distance between the shuttle and the telescope and brought the Columbia to a position about 800 m below the telescope. From there on, Scott Altman took over manual control and brought the Columbia to a position 12 m below Hubble. Richard Linnehan supported him by checking the distance to Hubble using a portable laser measuring device . From there, Nancy Currie used the robotic arm to grab Hubble and put it on the maintenance platform. It was attached there and connected to the shuttle's power supply. Four and a half hours later, commands were given to retrieve the solar collectors so that they could be exchanged during the first two exits. Furthermore, preparations were made for the first exit, which was to take place the following day. This included reducing the air pressure in the cabin to 10.5 psi (725 mbar).

Working on Hubble

From the fourth to the ninth day of the flight, an external mission was carried out daily to improve the performance of the telescope. In order to make this possible, two teams were formed to take turns doing the exits. John Grunsfeld and Linnehan formed the first team and took over exits one, three and five. Exits two and four were performed by James Newman and Michael Massimino . On all five exits, the inactive team was responsible for going through the checklists and tasks of the active team. During all exits, Nancy Currie maneuvered the shuttle's robotic arm. Scott Altman supported them. Duane Carey took on various tasks. Among other things, he was responsible for the video downlink.

The exits can be divided into two groups. In the course of the first three exits, almost all of the electronics were replaced. The aforementioned solar collectors and the Power Control Unit (energy control unit, PCU) were affected. The last two exits served to expand and improve the scientific possibilities with the installation of the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) and the restart of NICMOS (Near-Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer) by installing a new cooling system.

Renewal of the electronics

On the fourth day of the flight, Grunsfeld and Linnehan made the first of five exits. The main task was to replace the solar collector on the right side of the Columbia. To make this possible, some preliminary tasks had to be performed. Among other things, the manipulator Foot Restraint , a work platform for outboard work, was attached to the robot arm of the shuttle. Then they replace a fuse box in order to be able to release the already collapsed collector. This was temporarily stowed away and the new, more effective and smaller collector installed and unfolded in its former position. The exit ended with the packing of the old collector and preparations for further exits as well as an emergency return of the shuttle. The outer hatch was closed after seven hours and one minute.

The second exit from the mission, which was carried out by Newman and Massimino, initially went the same way as the exit the day before after a brief preparatory phase. The main difference was that the left collector was replaced instead of the right one. Then Newman got a set of gyroscopes, which should be installed as a replacement for the faulty set. Massimino meanwhile opened Hubble and began to dismantle the set. He then exchanged it with Newman and installed the new set in the position, while Newman stowed the old set in the position in which the new set had previously been. In addition, they exchanged two brackets which, after a brief examination, they deemed in need of replacement. After the final clean-up, the exit took seven hours and 16 minutes.

Due to a water leak in Grunsfeld's spacesuit, the start of the third exit was delayed, during which the PCU was supposed to be replaced. To do this, Hubble had to be shut down completely for the first time since launch. After the preparations, Linnehan first removed the Hubble batteries from the mains and covered the cable ends with a protective cover. In the meantime, Grunsfeld installed various heat protection mats at several Hubble points, which should ensure that Hubble does not cool down too much while it is switched off. He then brought more tools to Linnehan and went into the airlock to take in additional oxygen for the remainder of the seven-hour exit. At the same time, Linnehan began to disconnect 30 of the 36 connections of the Hubble power supply from the PCU. He swapped places with Grunsfeld and took the new PCU out of the payload bay. Grunsfeld broke the last six connections and took the old PCU out of its position. He swapped it for the new one at Linnehan and installed it in the position in which the old PCU was previously. While he was re-establishing the electrical connections, Linnehan stowed the old PCU and also refueled his suit with additional oxygen. He then did minor maintenance in preparation for the final two exits. Then he connected the batteries to the power grid and dismantled some of the heat protection mats. The exit, during which Hubble was without power for four hours and 24 minutes, ended after the cleanup with a duration of six hours and 48 minutes.

Expansion of scientific skills

During the fourth exit, carried out by the duo Newman and Massimino, after the preparatory tasks, they first worked together to unplug the Faint Object Camera (FOC) and then remove it from its position in Hubble so that Newman stowed it temporarily could be. The last of Hubble's original instruments was thus decommissioned. Together, they prepared the fifth exit by installing a power distribution board before starting to get the ACS out of its bracket in the payload bay and attach and connect it in Hubble. Finally they packed the FOC in the container that previously held the ACS and swapped positions. The next task was to assemble an additional electronic unit, which should provide the electricity for the new cooling system to be installed. For this it was necessary that various power connections had to be re-established. Finally, they removed the heat protection mats that remained from the third exit and returned to the airlock after the clean-up work and an exit time of seven hours and 18 minutes.

During the last exit from Grunsfeld and Linnehan, they installed the new cooling system for NICMOS after the preparatory tasks. To do this, they first prepared the device themselves by modifying the grounding and deactivating the old cooling system. Then they fetched the cooler and fixed it in Hubble so that Grunsfeld could connect it to the circuit. Linnehan meanwhile began to fetch the radiator belonging to the cooling system from the payload bay. They attached it to Hubble's exterior and connected it to the coolant circuit and the power grid. The cooler itself was also attached to the power grid. After extensive clean-up work, this exit ended after seven hours and 32 minutes.

Suspension and return

On the ninth day of the flight, preparations began for the resumption of Hubble and an unneeded reserve exit for Newman and Massimino. About three hours before the launch, Currie attached the Columbia's robotic arm to the Hubble anchor point. A little later, the transmission antennas were extended again and the Columbia was brought into a position that would enable Hubble's new solar collectors to charge Hubble's batteries. Two hours before the launch, Hubble was switched back to the internal power supply and disconnected from the shuttle's power supply. Shortly afterwards, Hubble was released from its holder and lifted out of the payload bay by Michael Massimino. Nancy Currie then took on the task of loosening Hubble's arm and bringing it into a safe position. After that, Scott Altman and Duane Carey began maneuvering the Columbia away from Hubble.

The next few days served, on the one hand, to allow the crew to recover from the five successive exits and, on the other hand, to prepare for the landing. During the tenth and eleventh day of the flight, all utensils that were no longer needed were stowed away and on the eleventh day of the flight the RCS hotfire, in which the auxiliary engines were checked for the landing, was carried out. Since there were no further problems, the Columbia was able to land at the Kennedy Space Center at 8:32 a.m. UTC the next day and complete this fourth maintenance mission with a duration of ten days, 22 hours, eleven minutes and 9 seconds.

Résumé

For the shuttle program this mission was a complete success. The Columbia and its crew worked perfectly together and with 35 hours and 55 minutes improved the record set during STS-61 for the total duration of exits during a mission by 27 minutes.

After several weeks of testing, Hubble was released for scientific use again. Both ACS and NICMOS worked perfectly and ACS partially exceeded expectations. With these results one was confident that during the fifth Hubble maintenance mission by installing the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC-3) and the Cosmic Orgin Spectograph (COS) to replace the WFPC-2 and the COSTAR optics correction as well as new batteries and Sensors could continue to operate until at least 2010. Then the telescope should be brought back to Earth. The Columbia was intended for both flights, as it was not suitable for an ISS mission due to its heavier construction.

Tragically, the plans for further Hubble maintenance missions became obsolete when the Columbia broke apart on re-entry into the earth's atmosphere during its next mission, STS-107 , and its crew perished in the process. As a result, all shuttle flights that did not lead to the International Space Station (ISS) were canceled without replacement, as in these cases the principle of the safe harbor could not apply. After the successful "return-to-flight" missions STS-114 and STS-121 as well as the development of a rescue mission profile , pressure from many scientists was given in and the fifth maintenance flight to the Hubble was re-included in the flight plan as the STS-125 .

See also

Web links

- Mission report in Raumfahrer.net

- NASA website of the Mission (English)

- NASA video of Mission (English)

- Video summary with comments of the crew (English)

swell

- ↑ Shuttle Status Report January 17, 2002. NASA, January 17, 2002, archived from the original on November 2, 2008 ; accessed on September 14, 2008 (English).

- ↑ Shuttle Status Report January 24, 2002. NASA, January 24, 2002, archived from the original on November 2, 2008 ; accessed on September 14, 2008 (English).

- ↑ Shuttle Status Report January 31, 2002. NASA, January 31, 2002, archived from the original on November 2, 2008 ; accessed on September 14, 2008 (English).

- ↑ Shuttle Status Report February 25, 2002. NASA, February 25, 2002, archived from the original on November 3, 2015 ; accessed on September 14, 2008 (English).

- ↑ Shuttle Status Report February 28, 2002. NASA, February 28, 2002, archived from the original ; accessed on September 14, 2008 (English).

- ↑ STS-109. NASA, November 23, 2007, accessed September 14, 2008 .

- ^ Columbia in the Encyclopedia Astronautica , accessed September 20, 2014.