Sentence structure in the Spanish language

A Spanish sentence , oración , is one of a word or several words existing self-contained linguistic unit with which a speaker or writer to the speech takes place. In contrast to the German one, the Spanish sentence , oración , is considered to be the smallest communicative entity with a complete meaning from a semantic point of view ; From a morphological point of view, the Spanish sentence contains at least one conjugated verb . Syntactically , the Spanish sentence works autonomously and independently. In order to be able to form a sentence, the language producer needs on the one hand:

- a lexicon that contains words as well

- a grammar that gives rules to those who combine words into larger units. The grammar represents a fund of structural patterns.

Structural patterns are descriptions of relationships (relations) between the linguistic elements or hierarchizations of relationship rules that can be formulated into regularities of how words can be combined into phrases and phrases into sentences. Usually the sentence has two elements, the subject, sujeto , and the predicate, predicado .

The Spanish sentence

Classification of the Spanish sentence

The Spanish sentence can be divided into two broad groups:

- the simple sentence, oración simple , and

- the compound sentence, oración compuesta .

Different forms of the Spanish sentence

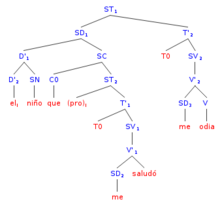

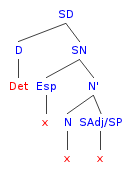

SN sintagma nominal , SD sintagma determinante , SV sintagma verbal , N nombre , adjetivo o pronombre , V verbo , P preposición , C complemento , CP construcción preposicional, D determinante

There are different types of sentences in the Spanish language , such as the

- Statutory sentence ( declarative sentence ), oración enunciativa

- affirmative sentence, oración enunciativa afirmativa .

- - Example: Juana vende un coche Juana sells a car.

- with two objects ( direct object, indirect object ).

- - Example: Juana vende un coche a su hija Juana sells her daughter a car.

- with predicative addition.

- - Example: Juana es muy ducho en negocios Juana is very skilled in shops.

- with adverbial determination.

- - Example: Esta mañana Juana ha leído modo de empleo This morning Juana read the instructions for use.

- negative sentence, oración enunciativa negativa .

- - Example: Juana no ha comprado un coche Juana did not buy a car.

- affirmative sentence, oración enunciativa afirmativa .

-

Question sentence (interrogative sentence ), oración interrogativa

- Interrogative sentences in direct speech , direct interrogative sentences,

- - Example: Dice ¿Has terminado tu jornada? He / she says: have you finished your working hours?

- Interrogative sentences in indirect speech , indirect interrogative sentences, oraciones interrogativas indirectas .

- - Example: Pregunta si ha terminado su trabajo He / she asks if he / she has finished his / her work.

The statement sentence belongs to the simple sentences . The basic word order in the propositional sentence is subject - predicate - object . If there is a direct and an indirect object, the direct object usually comes before the indirect object (in German it is the other way around).

- - Example: Florentina escribe una carta a su amiga Florentina is writing a card to her friend.

But if the direct object is much larger than the indirect object, this order is reversed. The indirect object (dative) now comes before the direct object (accusative).

- - Example: Florentina escribe a su amiga una carta de diez páginas y algunas fotografías Florentina writes her friend a card with ten pages and some photos.

- Subject - predicate - indirect object (dative) - direct object ( accusative ) - adverbial determination or - prepositional object.

The sequence of the individual clauses in Spanish has many possible variations:

- - Example: Florentina trabaja en una discoteca .

- Predicate - subject - adverbial determination.

- - Example: Trabaja Florentina en una discoteca .

- adverbial determination - predicate - subject.

- - Example: En una discoteca trabaja Florentina .

- Predicate - adverbial determination - subject.

- - Example: Trabaja en una discoteca Florentina .

- Subject - predicate - direct object (accusative) - indirect object (dative) - prepositional object - additions.

As it turns out, the parts of the sentence are more or less free in their position. They can be at the beginning of the sentence, after the verb or at the end of the sentence. This is especially true for the adverbs and the adverbial determinations. Despite these abundant possibilities to reverse the word order of the Spanish sentence, these are subject to certain restrictions:

- The verb or predicate must not come after subject and object - i.e. never in third position - and all verb forms belong together, there are no sentence brackets as in German sentences. Therefore no other word may be inserted between the auxiliary verb haber and the participle .

- Some language elements promote subject inversion , the subject comes after the verb.

- If the object is put in front, the repetition on the verb is usually done with a personal pronoun. However, please note the relevant exceptions.

- If you replace the objects with pronouns , you put the object pronoun in front of the verb, first the indirect object (dative; me, te, se, os ) and then the direct object (accusative; lo, la, los, las ).

- Personal pronouns ( me, te, nos, os, le, les, lo, la, los, las ) are appended before in the conjugated form, but afterwards to the infinitive, gerund and affirmed imperative.

- Negative particles always come before the verb, but before the personal pronouns (like me, te, nos, os, le, les, lo, la, los, las ) and before the reflexive pronoun se .

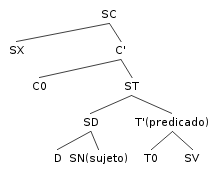

In the case of compound sentence types ( complex sentence ) in Spanish, the word order in main and subordinate clauses is the same (see also hypotax and paratax ). This is in contrast to German, where a subordinate clause is ended with a verb. In Spanish, however, you always have to pay attention to whether the indicative or the subjunctive is used in the subordinate clause.

Classification of the subordinate clauses

A distinction is formally made between the following types of subordinate clauses:

- oraciones subordinadas , which are introduced with a conjunction or subjunction or a conjunctive expression;

- Subject sentences , oraciones sustantivas de sujeto ;

- direct object sentences or with an accusative object , oraciones sustantivas de objeto directo ;

- indirect object sentences or with a dative object , oraciones sustantivas de objeto indirecto ;

- Attribute sentences , oraciones atributivas ;

- Relative clauses , oraciones de relativo ;

-

Adverbial clauses , oraciones circunstanciales . A subordinate clause is used instead of an adverbial determination . Adverbial clauses can be further differentiated into (here the most important):

- Causal clause ( justification clause ), oración causal

- Temporal clause , oración temporal

- Consecutive clause ( following clause ), oración consecutiva

- Final movement (intention, purpose ), oración final

- Conditional clause ( conditional clause ), oración condicional

- Concession clause (grant clause, counter rule), oración concesiva

The importance of coordinating conjunctions in sentence structure

The subordinating or subordinating conjunctions, conjunciones subordinantes , coordinate the connection in the sentence structure between a main clause and a subordinate clause . If subordinate clauses are directly subordinate to the main clause, it is a so-called hypotax , the subordinate clause is then also called a subordinate clause (of the main clause).

Sentence examples

The regular sentence structure in Spanish is:

Subject - verb (applies to all verb forms) - direct object (accusative in case terminology) - indirect object (dative in case terminology) .

This phrase can be reversed with certain restrictions.

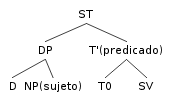

The Spanish sentence has at least one main clause, oración principal , or a main clause and a subordinate clause, oración subordinada . The latter sentence structures are called sentence structures , oraciones cláusulas . The concept of predication is central in classical grammar , in which a subject is assigned a property, a predicate, in the broader sense a verb or an action. In order to make further statements with this construction consisting of subject and predicate, the system was expanded to include additional clauses , such as the object , the adverbial definition and the attribute .

In simplified terms, a Spanish sentence is mapped as follows:

Wer „Subjekt“ macht „Prädikat“ was „direktes Objekt (in Kasusterminologie Akkusativ)“ für wen „indirektes Objekt (in der Kasusterminologie Dativ)“, unter welchen Umständen „adverbiale Bestimmung“ ? ¿Quién hace qué para quién, en qué circunstancias? Juana escribe una carta a su padre en la calle.

Adverbial determinations can also stand between the subject and the predicate. - example:

María en la calle escribe una carta.

If the direct and indirect object are replaced by a pronoun, the indirect or dative pronoun comes before the direct or accusative pronoun. - example:

Juana me lo ha dicho.

Pronouns are added to the infinite verb forms and given an accent. - Example infinitive:

Juana va a llegarte. Juana va a explicártelo.

If the indirect object (dative in case terminology) is longer than the direct object (accusative in case terminology) the order is reversed. - example:

Juana manda a su amiga un diario de cien páginas.

Predicative additions are placed immediately after the verb when they relate to the subject. - example:

Junana es muy apañada.

However, if the additions refer to the direct object (accusative in case terminology), they appear immediately after the object. - example:

Juana escribe un diario muy interesante.

As in other languages, the Spanish sentence can be subjected to sentence analysis . The sentence is broken down into its defined components in order to gain insight into the forms and functions of its parts as its sentence structure. A simple sentence about this. - example:

El gato come un pez. Die Katze frisst einen Fisch. Se lo come.

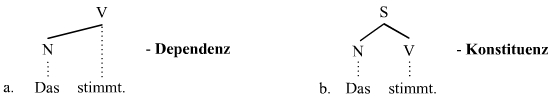

This sentence can be divided into three parts from the perspective of the dependency grammar and, on the other hand, from the perspective of the constituent grammar into two parts.

El gato come un pez. Subjekt Prädikat direktes Objekt. Satzanalyse nach der Dependenzgrammatik und die Begrifflichkeit (farbig unterlegt) der klassischen Grammatik

In the dependency grammar, the description of the dependency relationships in the sentence is in the foreground regardless of the linear arrangement of the individual words. Dependency is a "one-to-one relationship". Each element in the sentence (word or morph ) corresponds exactly to one node in the structure of the sentence. Constitution, on the other hand, is a "one-to-one or more relationship". There each element in the sentence (word or morph) corresponds to at least one node and often more than one. The difference is easy to see from simple tree structures. From the point of view of the grammar of dependency, the superordinate word is rain , while the subordinate word is dependency. Each word has only one rain but can have several dependencies. In contrast to classical grammar or constituent grammar, the dependency grammar neither names a subject-predicate structure nor does it give the subject a special position.

María da el coche a Juana. Maria gibt das Auto zu Juana. María se lo da. Maria ihr es sie gibt.

da / \ María el coche a Juana.

Subject indirect object pronoun (in case terminology dative) direct object (in case terminology accusative) The terminology of classical grammar for comparison.

El gato come un pez. Subjekt Prädikat Satzanalyse nach der Konstituentengrammatik

In the analysis, language reveals the various elements that structure a text, sentence, phrase or word. It is they who carry out the basic syntactic functions, e.g. B. represent subject, predicate and object. In the analysis, however, it is crucial not to equate form and function. - Examples:

* Wortgruppen

El gato Nominalphrase come Verbalphrase un pez Nominalphrase

A noun phrase NP, sintagma nominal SN represents a group or grouping of semantically and syntactically related words that contain a noun (in the sense of a noun ) and take on syntactic functions. The NP (SN) can also consist of the noun alone or of a stressed pronoun , pronombres tónicos . The verb phrase VP, sintagma verbal SV is also a group or grouping of semantically and syntactically related words, which has a finite verb form as an obligatory core (taking into account the pro-drop phenomenon ) and which in the sense of congruence according to person, number, tense and aspect is determined; from the point of view of classical grammar, it fulfills the function of the predicate.

* Funktion

El gato Subjekt come Prädikat un pez direktes Objekt

* Wortarten

el Artikel (bestimmt) gato Substantiv come finities Verb un Artikel (unbestimmt) pez Substantiv.

While the German sentence is characterized by a distance position and sentence brackets in the sentence structure. A distance position is given when two content-related parts of a sentence or two parts of a part of a sentence are separated from each other according to their position. In this word order, the content-related parts of the sentence "ha llegado" are right next to each other. - example:

María ha llegado el periódico. Maria sie hat die Zeitung bekommen.

First of all, an utterance , enunciado , must be separated from a sentence, oración . A sentence is first of all a compilation of lexical and grammatical units, which are characterized by a tiered, hierarchically ordered relationship structure. The grammatical sentence has a subject or sintagma nominal and a predicate, sintagma verbal . The latter in turn consists of the verb, verbo or the perífrasis verbal and the complementos del verbos . The core of the predicate can be a finite verb . Further parts of the sentence can be layered around this verb , such as the predicatives and adverbial determinations , complementos circunstanciales . The attributive determinations, complementos predicativos , in turn relate to the subject or objects. A Spanish verb cannot be placed after the direct object ( accusative in case terminology) or indirect object (dative in case terminology) at the end of a sentence. A verb can only appear at the end of the Spanish sentence if the sentence should only consist of a subject and a verb.

Thus, the following positions are possible: subject-verb-object (SVO) and also verb-subject-object (VSO). - example.

(Nosotros) hemos encontrado el coche robado. (SVO) Wir fanden das Auto gestohlen.

"Nosotros" stands for the subject and "hemos found" for the predicate, even if it is often not written or only written for specific purposes. Because the realization of the subject is not mandatory in Spanish, it can remain empty compared to other languages (null subject or pro-drop languages )

Gustarle algo a alguien. (VSO)

Subject-object-verb (SOV) as in Latin , - example, are not possible

Servus puellam amat. Der Sklave das Mädchen er liebt.

or Object-Subject-Verb (OSV).

The main characteristics of the Spanish sentence structure

- A verb must not come after subject and object (never take the third position, place) and all verb forms that appear in the same sentence belong together. No other word may be inserted between the auxiliary verb haber and the participle.

- Some factors favor subject inversion (subject after the verb);

- If the object is placed in front, with a few exceptions, the repetition of the verb by a personal pronoun must be observed.

- The position of the unstressed personal pronoun , it is attached to the verb in front of the conjugated form or with the infinitive, gerund and affirmed imperative.

- The negation always comes before the verb, but before the unstressed personal pronouns ( me, te, nos, os, le, les, lo, la, los, las ) and before the reflexive pronoun se .

All other parts of the sentence are more or less free in their position. They can be at the beginning of the sentence or after the verb or at the end of the sentence. This is especially true of the adverbs and adverbial expressions. The sentence adverbs, which refer to the whole sentence and express the speaker's opinion, can also appear at the beginning of the sentence, after the verb or at the end of the sentence, but must then be separated by a comma .

Congruence in the Spanish sentence

In inflectional languages , such as Spanish, there is a fundamental tendency to bring the words that are related to one another into a formal correspondence. The term “congruence” generally describes such a formal agreement, mostly in the categories of gender, number, case and person; as a related phenomenon, the agreement in tense and mode within a sentence can be cited. In general, congruence, concordancia gramatical in linguistics, is the agreement of characteristics in different linguistic elements within a syntactic domain (e.g. sentence or constituent ). In simple terms, it describes the agreement, for example with regard to person, number or gender in the corresponding words of the sentence components , i.e. with regard to their grammatical categories.

This means the alignment of different words that appear in the sentence in terms of person, number, gender and other possible features. In the Spanish language, for example, the finite verb and its subject are congruent in both person and number. A predicative adjective with the subject in number and gender, an attributive adjective and an article with its reference noun also in number and gender. - Examples:

Me gusta el coche. Mir gefällt das Auto. Me gustan los coches. Mir gefallen die Autos. ¿Os gustan los conciertos de Juan del Encina? Sí. También nos gusta escuchar música de Francisco de Salinas. Euch sie gefallen die Konzerte von Juan del Encina? Ja, ebenso uns gefällt die Musik zu hören von Francisco de Salina. Die Person-Numerus-Kongruenz ist im Spanischem obligat, die Genus–Kongruenz hingegen nur in einigen Prädikatkonstruktionen, so dem Passiv, den Partizipialperiphrasen. – Beispiele, beide Sätze in der Zeitform des Pretérito perfecto compuestos: He comprado una camisa y un chaleco amarillo. Ich habe gekauft ein Hemd und eine Weste gelbe. He comprado un abrigo y un sombrero negros. Ich habe gekauft einen Mantel und einen Hut schwarzen.

However, out of consideration for the semantic sense , it is possible to remove the congruence rule. - Examples, both sentences in the tense of the Pretérito perfecto simple

La mayoría comieron sin decir nada. Die Mehrheit sie aßen ohne zu sagen absolut nichts. La mayoría comió sin decir nada. Die Mehrheit sie aß ohne zu sagen absolut nichts.

The subject “la mayoría” is represented in the singular as shown in the use of the article, but semantically and content-wise it refers to a plurality. The predicate used in the form of the verb "comer" can therefore be used both in the plural and in the singular.

Common Terms

The syntax is part of the grammar and, as a system of rules, offers the possibility of creating sentences from words and phrases . These sentences can be broken down further into smaller building blocks, which are called constituents . A constituent, constituyente sintáctico is defined as

- A group of words that are treated as a unit by a syntactic rule.

It is (initially) irrelevant whether the constituent consists of one or several words or parts of speech . In the latter case, constituents can also be broken down into further subunits. As a result, a constituent structure or a constituent tree can be shown graphically.

The analyzed constituents have different grammatical features. The following terms are to be listed here. The phrase , in linguistics , denotes a closed (or maximum) syntactic unit, in contrast to units that still lack additions. So it is a special case of a constituent. Depending on different grammar theory, phrases are defined differently. In some constituent grammars , for example, individual words are counted among the phrases if they do not require any further additions, while dependency grammars only recognize a syntactic unit as a phrase if it consists of more than one word. In general, all languages are similar in that individual words are supplemented by further words, resulting in larger groups of words or phrases. Since the words in the word groups must have certain sequences in order not to be perceived as ungrammatical (syntactic regulations), it can be concluded that they must have a certain, abstract structure, which allows the individual different word groups to be represented in a grammatically correct manner. Such syntactic modules that can be changed and expanded are called constituents. The head of such a phrase determines the syntactic category of the entire phrase. If the head of a phrase is a noun , the phrase is a noun phrase ; if the head of a phrase is an adjective , the phrase is an adjective phrase , etc.

So every phrase has its own head , núcleo sintáctico . The head or nucleus thus represents the core element in a phrase insofar as it determines the grammatical characteristics of the entire phrase. The head or nucleus is the governing element is in the phrase as it is the grammatical features of other syntactic elements is determined ( Directorate ). Such an element, which forms the dependent counterpart to the head in a compound expression or phrase, is also called a dependency. The head is thus that part of a compound expression which itself bears the same characteristics as the overall expression and which thus represents the origin of the characteristics of the overall expression. It is said that the head projects or inherits its characteristics into the overall expression.

Syntactic category and function

It is important to distinguish between the syntactic category, which can initially be understood as parts of speech, and the syntactic function. The syntactic category shows a certain constancy and immutability in the characteristics of the individual parts of speech, so a noun remains a noun regardless of its function in the sentence. As constituents, syntactic categories take on certain syntactic functions or sentence functions, they are in certain relationships to one another. It is therefore important to separate the different levels of the theoretical constructs in which the terms are embedded in order not to confuse the syntactic function and the syntactic category . For example, the adverb is a syntactic category, whereas the adverbial definition is a syntactic function. This leads to important conclusions such as:

- there is no fixed correlation between the syntactic category and syntactic function;

- the same syntactic category, such as a noun phrase, can fulfill different syntactic functions in a sentence, for example as a subject, object, adverbial definition or as an attribute.

- conversely, the same syntactic function, such as an object, can be realized by different syntactic categories, by a noun phrase, by a prepositional phrase or by a subordinate clause.

Sintagma nominal or noun phrase

In German one speaks rather of “phrases” instead of “syntagmas”. Phrases form a syntactic category that stands between the word and the sentence level; they are complex constituents . In the noun phrase (NP), sintagma nominal (SN) , it is a group of related words created by the expansion of the noun's lexical category . On the one hand, the (preceding) determinants such as:

- Article , artículos (D) , el, la

- Possessive pronouns , posesivos (D) , mis, tus

- Demonstrative pronouns , demonstrativos (D) ,

- Numeralen , numerales

- Indefinite pronouns , indefinidos (D) , alguien

- Interjection , exclamativos (D)

- Interrogative pronouns , interrogativos (D)

But also the (trailing) additions, complementos are significant for noun phrases, sintagma nominal (SN) , like this:

- Adjectives , adjetivo

- Appositions , aposiciones

- Preposition , sintagma preposicional

Aquella traje rojo de Gil Pato

Sintagma verbal or verb phrase

Verb phrase (VP), sintagma verbal (SV) is used in linguistics to denote a phrase or a closed syntactic unit, the so-called head, core or nucleus of which is a verb. The verb phrase acts as a direct constituent of the sentence in the sense of the phrase structure grammar and contains a verb. Depending on the valence of the verb in the sense of the dependence theory, the number and type of (obligatory) additions, such as object, adverbial, vary. From this perspective, all elements are directly or indirectly dependent on the verb. Any number of free entries is also possible, although the boundary between mandatory and optional additions cannot always be precisely determined. The dependency-structural verb phrase is completely different to the verb phrase in the sense of the phrase structure grammar , especially to be interpreted in the generative school of transformation theory.

Abbreviations, Spanish and German terms

- ST sentencia u oración , sentence

- SN sintagma nominal , noun phrase

- SD sintagma determinante , determinant phrase

- SV sintagma verbal , verb phrase

- SX sintagma X , X-bar theory

- N núcleo sintáctico ( nombre , adjetivo o pronombre ), syntagmatic nucleus ,

- V verbo , verb

- P preposición , preposition

- C complemento sintáctico , complementador , complementer

- CD complemento directo ,

- CI complemento indirecto ,

- CP sintagma preposicional o construcción preposicional ,

- D determinant , determinative .

| "Adverbial Insertion" | Subject , sujeto | Predicate , predicado | indirect object , complemento indirecto or objeto indirecto (dative in case terminology ) | direct object , complemento directo or objeto directo (accusative in case terminology ) | indirect object , complemento indirecto or objeto indirecto (dative in case terminology ) | Prepositional object , complemento preposicional | Adverbials , complemento circunstancial | "Predicate insertion" | "Subject insertion" |

| Juana | explica | la situación | a José. | ||||||

| Juana | lee | un libro | muy excitante. | ||||||

| Juana | le gusta | a José. | |||||||

| Juana | piensa | en José. | |||||||

| Juana | le there | el bolígrafo | a José. | ||||||

| Juana | escribe | a su madre | un libro de quinientos páginas. | ||||||

| Juana | vive | en Valencia. | |||||||

| Juana | cambia | dólares | por euros. | ||||||

| Juana | le habla | a José | de religón. | ||||||

| Juana | pone | el bolígrafo | en el escritorio. | ||||||

| Juana | ha mostrado | a sus amigos | el camino. | ||||||

| Juana | piensa | en José. | |||||||

| Ella | (¤) | se | lo | ha mostrado. | |||||

| At the moment | (¤) | entraron | los invitados. | ||||||

| Mañana | Juana | irá a montar | en bicicleta. | ||||||

| Juana | irá a montar | en bicicleta | mañana. | ||||||

| (¤) | Juana | irá (¤) mañana a montar. | en bicicleta. |

Differences between German and Spanish sentence structure

The German sentence contains two Verbpositionen, which together form the sentence bracket form, this is characteristic of the German sentence. It describes the typical German sentence structure, a form of syntactic discontinuity, which occurs as soon as the predicate in the main clause has infinite parts in addition to the finite verb . Since the German declarative sentence has verb second position (V2 position), the finite verb is in front and the remaining, infinite part - either the prefix of a separable verb , a verb in the infinitive or a participle - is in the back of the sentence; the two then “clasp” the middle field of the sentence, so to speak . The same applies to questions and other types of sentences with verb-first position . This syntactic discontinuity of the German SOV language contrasts with the syntactic linearity of the SVO languages , which also includes Spanish.

literature

- Francisco Javier Grande Alija: Las modalidades de la enunciación. Universidad de León, León 1996, dissertation

- Helmut Berschin , Julio Fernández-Sevilla, Josef Felixberger: The Spanish language. Distribution, history, structure. 3. Edition. Georg Olms, Hildesheim / Zurich / New York 2005, ISBN 3-487-12814-4 .

- Ignacio Bosque; Javier Guitiérrez-Rexach: Fundamentos de Sintaxis Formal. (1st ed.), Grupo Editorial Akal, Madrid 2009, ISBN 978-84-460-2227-5 .

- Noam Chomsky : El conocimiento del lenguaje, su naturaleza, origen y uso. Alianza, Madrid 1989.

- Dee L. Eldredge: Teaching spanish, my way. Xlibris LLC, 2014, ISBN 978-1-4931-2657-6 , pp. 68 f.

- Ginés Lozano Jaén: Cómo enseñar y aprender sintaxis. Modelos, theorías y prácticas según el grado de dificultad. Cátedra, Madrid 2013, ISBN 978-84-376-3032-8 .

- Arne Reimar Kirchner: A head-driven phrase structure grammar for Spanish noun phrases. Dissertation, University of Göttingen, 1999

- María Jesús Fernández Leborans: Los sintagmas de español. I. El sintagma nominal. Arco Libros, Madrid 2009, ISBN 978-84-7635-548-0 .

- Hortensia Martínez: Construir bien en español: La correccíon sintáctica. Butterfly, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-89657-775-1 .

- Ramón Cerdá Masso; Alberto Jiménez Hipólito Remondo, M.ª Ángeles Andrés: Diccionario de lingüística. (1st ed.), Anaya, Madrid 1986, ISBN 84-7525-366-0 .

- Benedikt Ansgar Model: Syntagmatic in a bilingual dictionary . Lexicographica. Series Maior, De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2010 ISBN 3-11-023222-7

- Ingrid Neumann-Holzschuh: The arrangement of parts of the sentence in Spanish. A diachronic analysis. Vol. 284 supplements to the journal for Romance philology, Max Niemeyer, Tübingen 1997, ISBN 3-484-52284-4 .

- Gabriel Ángel Quiroz Herrera: Los sintagmas nominales extensos especializados en inglés y en español descripción y clasificación en un corpus de genoma. Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Institut Universitari de Lingüística Aplicada, Barcelona 2005

Web links

- Sentence structure, word order, sentence structure. Hispanoteca, Justo Fernández López

- Justo Fernández López: The Spanish sentence structure. Hispanoteca, pp. 1-12.

- Clasificación de las oraciones en español - Classification of sentences in Spanish Hispanoteca, Justo Fernández López

- Las oraciones subordinadas. www.guanajuato.inea.gob.mx

- Mi-Young Lee: SVO's riddle when learning German - Why is SVO so easy, while SOV is so difficult to produce? Journal for Intercultural Foreign Language Teaching, Didactics and Methodology in the Field of German as a Foreign Language, ISSN 1205-6545 Volume 17, Number 1 (April 2012), pp. 75–92

- Alfonso Sancho Rodríguez: La oración compuesta, coordinadas, yuxtapuestas - subordinadas.

Remarks

- ↑ from engl. pro-drop short for pronoun dropping , "omitting a pronoun"

- ↑ One can describe the inversion as follows: the subject follows the finite verb form in question clauses, after preceding adverbials, object noun phrases and subordinate clauses.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Elena Santillán: Spanish Morphosyntax. A study book for teaching, learning and practicing ; Narr, Tübingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-8233-6980-6 , p. 16

- ↑ Spanish. An introduction to grammar. Sentence structure. wikibooks

- ^ Hortensia Martínez: Construir bien en español: La correccíon sintáctica. Butterfly, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-89657-775-1 , p. 60.

- ^ Alfonso Sancho Rodríguez: La oración compuesta.

- ↑ La oración compuesta.

- ↑ Justo Fernández López: sentence structure, word order, sentence structure. El orden de las palabras en la oración. Colocation de los elementos oracionales.

- ↑ Claudia Moriena; Karen Genschow: Great Spanish learning grammar: rules, examples of use, tests; [Level A1 - C1]. Hueber Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-19-104145-8 , pp. 602-622.

- ^ Ingrid Neumann-Holzschuh: The arrangement of parts of the sentence in Spanish. Supplements to the Journal for Romance Philology, Volume 284, Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 1997.

- ^ Hans-Georg Beckmann: New Spanish grammar. dnf-Verlag, Göttingen 1994, ISBN 3-9803483-3-4 , p. 320.

- ↑ DUDEN. 8th edition. The grammar. 2009, p. 1027.

- ↑ sentence structure - Orden de los elementos colocación de oracionales (Recop.) Justo Fernández López. Hispanoteca.eu

- ↑ Elise Richter: On the development of the Romance word order from the Latin. Max Niemeyer Verlag , Halle (Saale) 1903 ( archive.org ).

- ^ Hans-Georg Beckmann: New Spanish grammar. dnf-Verlag, Göttingen 1994, ISBN 3-9803483-3-4 , p. 320.

- ↑ compare the conceptual system of predicate logic

- ^ Hans-Georg Beckmann: New Spanish grammar. dnf-Verlag, Göttingen 1994, ISBN 3-9803483-3-4 , pp. 321-322.

- ↑ Reinhard Kiesler : Speech system technology. Introduction to sentence analysis for Romanists. Winter, Heidelberg 2015, ISBN 978-3-8253-6409-0 , pp. 2–3

- ↑ In the Spanish sentence, however, the contact position applies. Slide cutting position Justo Fernández López, hsipanoteca.eu

- ^ Georg Bossong: Diachrony and pragmatics of the Spanish word order. Magazine f. Romance Philology 100 (1984) pp. 92-111.

- ↑ Rolf Kailuweit: Pro-drop, congruence and "optimal" Klitika. A description approach within the framework of the role and reference grammar (PDF). In: Carmen Kelling, Judith Meinschaefer, Katrin Mutz (eds.): Morphology and Romance Linguistics. XXIX. German Romance Day, Saarbrücken 2005, Department of Linguistics at the University of Konstanz, Working Paper No. 120.

- ↑ sentence structure, word order, sentence structure. El orden de las palabras en la oración. Colocation de los elementos oracionales. Justo Fernández López. hispanoteca.eu

- ↑ George A. Kaiser: verb placement and Verbstellungswandel in the Romance languages. ( Memento of the original from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Max Niemeyer Verlag , Tübingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-484-30465-9 .

- ^ Spanish sentence structure - El orden de las palabras. Hispanoteca.eu

- ↑ Peter Gallmann: Nouns - Syntactic control of case inflection. University of Jena, summer 2014, pp. 1–7

- ^ The concordance / congruence - La concordancia. Justo Fernández López, hispanoteca.eu

- ↑ Hadumod Bußmann (ed.) With the assistance of Hartmut Lauffer: Lexikon der Sprachwissenschaft. 4th, revised and bibliographically supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-520-45204-7 , pp. 363-364.

- ^ Helmut Berschin, Julio Fernández-Sevilla, Josef Felixberger: The Spanish language. Distribution, history, structure. 3. Edition. Georg Olms, Hildesheim / Zurich / New York 2005, ISBN 3-487-12814-4 , p. 269.

- ↑ Peter Auer (Ed.): Linguistics. Grammar interaction cognition. JB Metzler, Weimar 2013, ISBN 978-3-476-02365-0 , p. 137 f.

- ↑ Peter Gallmann, Horst Sitta: Sentences in the scientific discussion and in result grammars. Günther Drosdowski on his 65th birthday , Journal for German Linguistics (ZGL) February 20 (1992). Pp. 137-181.

- ^ Andrew Carnie (2010): Constituent Structure , 2nd edition, Oxford University Press. P. 18

- ↑ Constituent grammar is primarily associated with the works of Leonard Bloomfield (1933), Rulon Wells (1947), and the young Noam Chomsky (1957). The dependency grammar is based on the theory of Lucien Tesnière (1959); see also Ágel et al. (2003/6).

- ^ Christian Lehmann: Syntactic functions. October 1, 2016

- ↑ Johannes Kabatek; Claus D. Pusch: Spanish Linguistics: An Introduction. Gunter Narr Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-8233-6404-7 , pp. 104-106.

- ↑ Apuntes de sintaxis. Pp. 1-5

- ^ Helmut Berschin , Julio Fernández-Sevilla, Josef Felixberger: The Spanish language. Distribution, history, structure. 3. Edition. Georg Olms, Hildesheim / Zurich / New York 2005, ISBN 3-487-12814-4 , p. 261.

- ^ John N. Green: Spanish. In: Martin Harris, Nigel Vincent (Eds.): The Romance Languages. Croom Helm, London 1988, pp. 79-130.