Lormont Castle

The Lormont Castle ( French Château de Lormont ) is the former summer residence of the archbishops of Bordeaux in the French city of Lormont in the Gironde department ( region Nouvelle-Aquitaine ). It is also known as the "Castle of the Archbishops" ( French Château des Archevêques ) and the "Castle of the Black Prince" ( French Château du Prince Noir ). The latter name comes from the fact that Edward of Woodstock , who was also called the Black Prince , is said to have spent part of his life in a previous castle in the 14th century, according to local traditions .

The former farm buildings stand since 13 December 1991 as a monument historique under monument protection .

history

Ceramic shards that were found during an excavation at the site of the castle in 1975 prove that the castle area was already inhabited in the Gallo-Roman period . However, information about a high medieval ducal castle at this location originally came from some local historians of the 19th century who, based on events related to the Aquitaine ducal family and Lormont, inferred the existence of a castle complex. However, there is a lack of both archaeological and archival evidence for this assumption, which has been presented by various authors in publications over the past 150 years no longer as a hypothesis but as a fact.

The first reliable mention of a stately home dates from 1330 and lists the Archbishop of Bordeaux as the owner. Nothing is known about this complex other than that it had its own chapel and that it could have been destroyed in the French Wars of Religion . From 1626, the cardinal and archbishop François de Sourdis had a new building built as a summer residence for his diocese by the builder Henri Roche on the medieval foundations of the destroyed previous building. When he died in 1628, not all of the buildings were finished. The main work came to an end around 1630, and only François' nephew Henry de Béthune completed one of the two lodgings between 1654 and 1662 .

The archbishops of Bordeaux used the castle as a country seat and summer residence until the French Revolution . While the Fronde was captured and devastated by royal troops, it was restored shortly afterwards (until around 1670). After 1744 repairs were made to the system again. In 1781, Archbishop Ferdinand-Maximilien Mériadec de Rohan-Guéméné decided not to repair the castle again, but to have it laid down with royal permission in order to then build a new building. Until the outbreak of the French Revolution, only a small part of the complex had been demolished. It was confiscated as national property in 1789 and partially looted . At that time there was still a wing of the farm building including the gate , the preserved part of the archbishop's lodgings and the area with guest accommodation and offices. Part of the latter was torn down during the revolution. In 1792 the state sold the approximately 30,000 square meter palace area with the buildings to the Peixotto family. It came from her through the Bourgade and Expert families in 1876 to the native Prussian Georg Schacher. At that time most of the buildings in the complex were in bad shape. Schacher had the ruinous parts torn down between 1876 and 1883, so that only a monumental fountain and a pavilion of the wing with the guest accommodation remained. This was repaired according to plans by the architect Alphonse Blaquière and expanded with new buildings in the eclectic style. Schacher also had the remaining farm buildings restored and a new wing added to them.

From 1930 the property belonged to the Ladouch couple, who emigrated to Argentina before the outbreak of World War II . Germans used the castle from July 1940 to August 1944. They had to vacate it for forces of the Forces françaises de l'intérieur , who stayed there until January 1945. At the end of the war, the castle was looted and in ruins, and the owners did not have it restored. They sold the property on September 1, 1956 for 2.9 million francs to a previous tenant, Mrs. Godel. She died in 1959. In 1969 the castle belonged to the Le Toit Girondin housing association. At that time, a large part of the palace park had already been destroyed by the construction of the Pont dʼAquitaine motorway bridge over the Garonne , which began in 1962 . In 1978 an association was founded with the aim of saving the castle from final ruin. Together with the local history society of Lormont, he succeeded in placing part of the palace complex under monument protection in 1991 and demolishing it was no longer possible. However, this did not prevent the then owner from selling the valuable monumental fountain from the 17th century in 1995 for 720,000 francs and having it dismantled. Despite a tough legal process, the well did not return. For ten years the buyer then tried in vain to resell the historical building material.

Then better times began for the fountain - as for the entire palace area. Meanwhile, the French state bought the ruinous facility in 1997. The city of Lormont bought it from him for 76,000 euros and then sold it to Norbert Fradin for the same price. Fradin had previously acquired the Villebois-Lavalette Castle and successfully restored it . From 2007, the repair and maintenance work began under him. The existing pavilion was restored and converted into office space while preserving the few remaining historical structures. The listed farm buildings were changed so that they now house a restaurant. The architect Bernard Bühler provided the designs for the restoration and alterations. The new lord of the castle also bought the dismantled fountain back for 100,000 euros and had it rebuilt in its original location.

description

Existing buildings before 1789

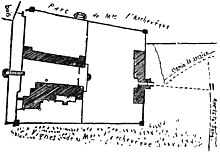

The appearance of the complex before the French Revolution is passed down through texts and a site plan. After the end of all construction activities in the 17th century, Lormont Castle was a complex whose buildings were located within two courtyards and whose floor plan was trapezoidal . The area was surrounded by a circular wall, which was preceded by a dry trench all around . Small, square watchtowers stood at their corners. Access was from the east, via a drawbridge and through a gate in the middle of the east wing of the farm buildings. A first courtyard could be reached through the driveway, on the north, south and east sides of which there were economic buildings such as stables, barns and staff quarters. There was also a castle chapel for the servants , which later served as a greenhouse in the 19th century. To the west of the first courtyard was a second courtyard, separated from the first by a wall. Inside were two elongated building complexes that stood parallel to each other. The southern one was called the Archbishop's Logis ( French Logis de lʼArchevêque ). The private and state rooms of the archbishop and his relatives were located in it. The northern complex was called the Logis of the foreigners ( French Logis des Étrangers ). There were accommodations for guests, a dining room, a game room and offices. To the west of the second courtyard, outside the curtain wall (and thus beyond the moat), was a castle park with terraces , artificial grottos and a game reserve. The southern slope of the hill on which the castle stood was also used as a vineyard from the 16th century .

Today's building stock

Of the buildings of the 17th century, only the east wing of the farm buildings and a pavilion for the lodging of the foreigners are preserved today. They were supplemented with extensions in the 19th century. The foundations of the former stately chapel in the archbishop's logis were uncovered during an excavation and can be seen today in the area of the former palace park.

Access to the palace complex is still today from the east through the preserved, 60-meter-long wing of the farm building, which in the basement could have buildings from the 12th century. The wing was mostly made of quarry stone and is plastered . Today, a brick, two-arched bridge leads over the remains of the former ditch to the gate building with a triangular gable and ox-eye . In contrast to the rest of the wing, the facade of the gate is made of stone . Above its arched gate, which is flanked by pilasters , there is a relief depicting the Mother of God and her child, who are surrounded by a host of angels. In addition, the coat of arms of Cardinal Sourdis is incorporated into the scene. In the basement of the east wing, some graffiti from the 15th century have been preserved. At the northern end of the wing, a second wing joins it to the west at a right angle. This is younger than the east wing and dates from the last quarter of the 19th century.

Today's Logis consists of a Louis-Treize- style pavilion , which was supplemented to the west in the 19th century by two buildings in the eclectic style. The pavilion is a rectangular, three-storey building with a high, slate- hipped roof . Its facade is rusticated just like that of the west building . The central building has two full and one mezzanine floors and is thus lower than its two neighboring buildings. In front of its ground floor with the portal of the logis are four pillars with a strong cornice with the coat of arms of the de Sourdis family. On the north side of the central building there is a two-flight flight of horseshoe-shaped stairs . The westernmost of the three logis buildings has a facade on its western side facing the Garonne. Between two crenellated , polygonal corner towers there is a colonnade with four pillars, which also support a balcony with a stone balustrade . To the east, the pavilion is adjoined by a low, single-storey extension with a flat roof, the eaves cornice of which carries a stone balustrade.

Not far from the lodge is a mighty fountain, which was built there around 1660 by Henry de Béthune, nephew of the French finance minister Maximilien de Béthune . On the edge of the fountain there are four fluted columns with a stone hood . The entire structure reaches a height of over five meters. The well shaft is 55 meters deep.

Hardly anything is left of the former palace park today. However, remains of the earlier garden structures such as stairs and fountains could still be preserved below its current floor level.

literature

- FA: Le château historique de Lormont. In: Revue Catholique de Bordeaux. Favraud Frères, Bordeaux 1884, pp. 38-45, 347-354, 431-438, 506-516.

- Paul Rodié: Lormont. In: Yvan Christ (ed.): Le Guide des châteaux de France. Gironde. Hermé, Paris 1985, ISBN 2-86665-005-0 , pp. 91-93.

- Jean-Luc Solé: Gironde, la fontaine du château de Lormont. In: Sites et Monuments. No. 160, January-March 1998, ISSN 0489-0280 , p. 16 ( digitized version ).

- Jean-Luc Solé: Le château de Lormont dit “Le château du Prince Noir”. In: Aquitaine Historique. No. 20, January-February 1996, ISSN 1252-1728 , pp. 2-6.

- Gironde. Le château de Lormont et sa fontaine. In: Sites et Monuments. No. 153, April-June 1996, ISSN 0489-0280 , p. 25 ( digitized version ).

Web links

- Entries of the castle in the base Mérimée : entry 1 , entry 2

- Online dossier on Marie-Hélène Maffre's castle from 2004

Footnotes

- ↑ Information on the palace complex on the website of the City of Lormont , accessed on November 29, 2018.

- ↑ a b c Entry 1 of the castle in the Base Mérimée of the French Ministry of Culture (French)

- ↑ Compare Paul Rodié: Lormont. 1985, pp. 91–92 and the online dossier on Marie-Hélène Maffre's castle from 2004, p. 1.

- ↑ a b Paul Rodié: Lormont. 1985, p. 92.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Entry 2 of the castle in the Base Mérimée of the French Ministry of Culture (French)

- ↑ Information according to the online dossier on Marie-Hélène Maffre's castle from 2004, p. 2. Paul Rodié, on the other hand, states that the work had already been completed in 1614. See Paul Rodié: Lormont. 1985, p. 92.

- ↑ a b F. A .: Le château historique de Lormont. 1884, p. 39.

- ↑ a b c d e Gironde. Le château de Lormont et sa fontaine. 1996, p. 25.

- ↑ a b c d e f Castle history on totila.centerblog.net , accessed on November 29, 2018.

- ^ A b Jean-Luc Solé: Gironde, la fontaine du château de Lormont. 1998, p. 16.

- ↑ a b Le Prince noir sort de lʼombre. In: Lormont actualités. No. 47, 2005, ISSN 1274-6037 , p. 15 ( PDF ; 2.6 MB).

- ↑ a b Le Prince noir sort de lʼombre. In: Lormont actualités. No. 47, 2005, ISSN 1274-6037 , p. 17 ( PDF ; 2.6 MB).

- ^ FA: Le château historique de Lormont. 1884, p. 435.

- ↑ a b F. A .: Le château historique de Lormont. 1884, p. 436.

Coordinates: 44 ° 52 ′ 41.9 ″ N , 0 ° 31 ′ 46.9 ″ E