St. Remberti pen

The St. Remberti Stift is the oldest surviving social institution in Bremen and one of the oldest in Germany. Originally served the monastery founded in 1305 at the latest as leprosy - Hospital and later as a poorhouse and retirement home . Today the St.-Remberti-Stift is a residential complex for the elderly with an attached nursing home . The historic buildings of the monastery in the Mitte district have been under monument protection since 1973 .

prehistory

In the Middle Ages there was no state-organized medical care in Bremen; it was only from 1511 that a city physician - a community doctor paid by the city council - was appointed. In addition to the care of sick people by relatives or - in the case of wealthy citizens - by servants and bathers , for a long time only minimal care existed through Christian- run hospitals (forerunners of today's hospitals ), which were mostly founded as hostels for pilgrims and which provided support for needy and sick people Saw people as their religious duty. In Bremen there was the St.-Jürgen-Gasthaus (since 1226 at the latest), the St.-Gertruden-Hospital (since 1366), and the St.-Ilsabeen-Gasthaus (since 1499).

Due to the poor hygienic conditions in the city, cholera , smallpox and plague epidemics broke out again and again , claiming many deaths such as in the years 1350, 1464, 1521 or 1577. In the 12th and 13th centuries, there was also an increase in Europe the leprosy associated with the Crusades . Bremer also took part in the crusades with several ships and together with Lübeckers founded a first field hospital near Akkon to care for sick and injured crusaders, from which the Teutonic Order later emerged. When leprosy also appeared in Bremen, the council decided around 1300 to found a hospital for the care of the sick, the St. Remberti Hospital.

The St. Remberti Hospital

In order to reduce the (supposedly high) risk of infection, the hospital was relocated outside the city walls in front of the bishop's gate near the village of Jericho . The exact time of the foundation of the monastery is uncertain, as no deed of foundation has survived. A document from the year 1226 may already refer to the Remberti Hospital, the earliest direct evidence comes from the year 1305, when the Kerckherr to Sunte Remberde received a donation - the pen must have already existed at this point in time. The foundation was named after Bishop Rimbert (830–888), who was already considered a saint in the Middle Ages and was venerated for his special care for the poor and the sick.

The hospital initially consisted of a few simple buildings and a chapel . Around 1350 the hospital was probably destroyed during the archbishop's feud, but was then rebuilt. At the beginning of the 15th century the chapel was replaced by the first small collegiate church . Around 1410, the complex consisted of the church, a few houses for the sick and a farmyard that provided the monastery with essentials. The monastery was administered by a bailiff , who was under the supervision (the patronage ) of the council, who was represented by two innocent chiefs or hospital masters (the procuratores or provisional ), one citizen and one councilor, later even both chiefs had to be councilors be. Well-known chiefs were u. a. the mayors Johann von der Trupe , Heinrich Krefting , Hermann Wachmann and Wilhelm von Bentheim .

The priests of the monastery, who were also appointed by the council, were also responsible for medical care until the 16th century. The pen seal, which is preserved on a document from 1426, shows Lazarus combined with the inscription Sigillum Infirmiorum in Brema . Admission, treatment and food to the hospital were free of charge. A House Rules (the handed in a copy of the 16th century) governed in detail the rights and duties of the residents of the pen, some of which remained in the hospital for a lifetime, because leprosy rarely been fatal, but there was hardly any chance of recovery.

Until the middle of the 16th century there was no support for the monastery from the city. The institution was financed primarily through gifts for the salvation of the soul . The monastery received donations from wealthy citizens in the form of land, interest or natural goods (clothing, food, wine and beer, wood, oil, wax, etc.). In return for the sometimes substantial donations, prayers, supplications and soul masses were held for the donors in the St. Remberti Church . In addition, maids of the monastery regularly went through the city in a so-called “bell cart” to collect alms . A list of the two monastery chiefs, Mayors Johann von der Trupe and Marten Baller, from 1512 shows that the monastery had considerable property in Bremen, the suburbs and the surrounding area, in addition to financial assets of 2,270 Bremen marks .

In 1511 von der Trupe and Baller created the first surviving statute for the monastery with the Sunte Remberte Gasthuses pen book, some of which remained valid until the 19th century, e.g. B. Paragraph No. 1 (in Low German ):

- “ To deme first, we dar kumpt before enen Provener, de brynget myt sick al syn Gudt and bruket des syneme Levedaghe unde theret dar aff na honesty, unde na synme Dode so kumpt to nuttichheit des vorscreven Huses, what the blyfft baven syne bigrafft. "

- (“To the first, who comes as a beneficiary, he brings with him all his possessions, and uses this his life, and lives on it fairly, and after his death the house mentioned above comes at the disposal of what remains after deduction of the funeral expenses. ")

While only leprosy patients were admitted in the 14th and 15th centuries, the monastery increasingly accommodated other patients as the number of leprosy patients slowly declined. With the conversion of the former St. Johannis monastery into a municipal hospital in 1531, more and more healthy (old) people moved into the monastery, who, in contrast to the sick and disabled, had to “shop”. This marked the beginning of St. Remberti's change from a hospital to an old people's home with Pröven .

The pen during and after the Reformation

With the implementation of the Reformation in Bremen from 1522 on, there were various far-reaching changes in the St. Remberti monastery. During the Schmalkaldic War in 1547, imperial troops moved towards Bremen. In order to get a clear field of fire from the city fortifications and to offer the enemy no cover, all buildings in the Remberti suburb were demolished at the beginning of March 1547, including the monastery buildings and the church. When the imperial troops finally had to withdraw after two unsuccessful sieges of Bremen and were defeated in the Battle of Drakenburg , the monastery was able to quickly rebuild thanks to its real estate and assets. First about ten small houses were built, which were grouped around a farm yard.

The orientation of the monastery changed completely from the care of the sick - who were cared for in the hospitals that were now in existence - to the care of old and needy people. With the end of the “ indulgence trade ” and the associated donations for the salvation of the soul in Reformed Bremen, one of the monastery’s main sources of income collapsed. In return, Protestantism was accompanied by a strengthening of the Christian commitment to charity for its own sake.

In 1596 the St. Remberti parish was founded and a parish church was built for the grown Remberti suburb to replace the destroyed collegiate church , where numerous small farmers and traders, so-called Höker , had settled. It was the first church building in Bremen after the Reformation. He was kept very simple and consisted of a longhouse in half-timbered with roof skylights . Inside there were no pictures and no decorations except for the Bremen coat of arms and the coat of arms of the rulers. The building was inaugurated on October 7, 1596. From then on, the newly founded parish of St. Remberti also included the episcopal villages of Schwachhausen and Hastedt in addition to the Pagenthorn peasantry from town of Bremen . Also in 1596 a school was attached to the community, the Remberti School , which existed until 1970.

The St. Remberti pen and the community were of the theological conflicts between Reformed and Lutherans concerned, especially as the teaching in the city-state Calvin prevailed, the archbishopric of Bremen , the Luther . From 1596 to 1831 (i.e. until after the annexation of Hastedt and Schwachhausen to Bremen) there were only Reformed preachers, then by decree of the council one Reformed and one Lutheran at the same time. With the Bremen church ordinance of 1596, deacons came to the Remberti congregation as volunteer workers - initially two, later six (four Reformed and two Lutheran).

Originally accommodation in the monastery was free and shopping in the monastery was voluntary, but from the 17th century it became the norm. At the end of the 16th century, 200 marks had to be paid for lifelong right of residence, and an additional 30 marks for lifelong food and fuel. The less well-off could share a benefit with another resident for half the amount. Despite the relatively high amounts, the demand for places in the monastery was so great that there were soon waiting lists.

Shaped by the Calvinist work ethic, which combined a frugal lifestyle with successful business, the fortune of the monastery increased steadily over the years. According to Hermann Wachmann's list, the income from loans, Meier interest , house rents, collections and other income in 1636 amounted to exactly 594 marks and 24 Grote and rose steadily:

- 1668–1677: an average of 954 thalers

- 1723: 1883 thalers

- 1760–1800: an average of 2740 thalers

The monastery could thus be run from its own resources - the council and citizens (especially merchants) even borrowed money from St. Remberti. In 1677, the monastery had bonds and festivals of around 100 people. In addition to the values of its land, the monastery was one of the wealthiest institutions in Bremen in the 17th and 18th centuries. Since the control of the assets was sometimes incomplete, there were some cases of embezzlement in the 18th century .

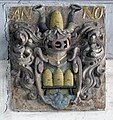

Bremen was spared major destruction during the Thirty Years' War , but the suburbs and villages outside the city fortifications, which were massively reinforced in the 17th century, were in a difficult situation. There were looting, requisitions and billeting by various troop units. The buildings erected after the Schmalkaldic War were therefore in poor condition after the Thirty Years' War and had to be gradually replaced. In addition, the monastery needed additional living space in order to be able to meet the increasing demand. The 24 ½ prebends that existed in 1643 became 30 ½ plus apartments for the priests, the teachers of the Remberti School and the monastery bailiff by 1671. The coats of arms of the two rulers Heinrich von Aschen and Hermann Wachmann with the inscription ANNO 1650 still bear witness to the expansion today .

As a result, there were incidents that made it difficult for the pen to exist. In 1688 some houses of the monastery were destroyed by arson and in 1700 the poor relief of St. Remberti was stolen. During the Seven Years' War , the monastery was occupied four times and used as quarters and an auxiliary hospital (in 1757 and 1758 by French troops and in 1758 and 1761 by English troops). Nevertheless, the St. Remberti Stift was so wealthy that it was able to support other institutions on behalf of the council: from 1690 the poor hospital and hospital in the new town with 100 Reichstalers annually and from 1701 the Michael’s Church in Utbremen with 75 Reichstalers annually .

Up until the 19th century, the monastery supplied itself with food through its Meierhöfe . The Meier were obliged to deliver fixed quantities of grain, beans, butter, eggs, etc. In the course of time, the deliveries in kind were converted into cash benefits in order to reduce the problems of delivery, stock keeping and planning.

The old half-timbered church from 1596 had become dilapidated in the 18th century. In 1736, a new building was approved by the council, which was inaugurated on September 21, 1738. The new church was built in brick as a hall church modeled on the St. Pauli Church in Neustadt for 14,230 Reichstaler. The long side of the building was divided by pilasters into four window fields and on the narrow side into two window fields. The church was closed off by a hipped roof with a turret and a lantern for the bell, crowned by a tower ball with a wind vane .

In 1781 the monastery consisted of the church, the preacher's and schoolmaster's houses, a “gentleman's room” for assemblies and the meetings of the rulers, a large warehouse and 25 small houses each with two to three rooms, a chamber, a kitchen and a floor.

The pen in the 19th century

During the French period at the beginning of the 18th century, there were further changes in the monastery through the abolition of the Meierrecht. After a first decree of the Napoleonic administration, a corresponding ordinance in the democratic constitution of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen dated April 5, 1849 stipulated that all manorial and similar basic charges were removable , that is, that the Meier had the right of ownership to his Meier property from his landlord could acquire. This right was retained in the conservative constitution of 1854. So the monastery had to gradually give up its Meierhöfe. Among other things, Johann Smidt had acquired a piece of land with Meierrechte of the monastery going as far as Kohlhökerstraße for his house on Contrescarpe in 1805 , which he replaced in 1842 by paying 281 marks. At the end of the 19th century, all of the monastery's Meierhöfe were finally closed.

In 1841 the parish was separated from the monastery by a resolution of the council and the citizenry in order to better take into account the different tasks of both organizations. In 1854, the administration of the monastery was handed over to a newly formed commission made up of six administrators by resolution of the Senate . In addition to the St. Remberti Stift, she was also entrusted with the supervision of the St. Catharinen Stift and the St. Ilsabeen Stift .

In the 1840s it was decided to renovate and expand the facility, as the old buildings no longer met the requirements and demand continued to grow; In addition, the monastery had sufficient capital from the mid-19th century when the Meierhöfe were replaced. Between 1843 and 1870, the master builders Diedrich Christian Rutenberg , Diedrich Seekamp and Johann Bellstedt gradually built new buildings in the classical style. The plant now consisted of a U-shaped square , on the west by the Rembertistraße , to the south by Rembertikirchhof and in the east of the Hoppe Bank has been limited. To the north, the buildings of the monastery were loosely distributed between Adlerstrasse , Mendestrasse and Dobben . The monastery courtyard inside the area was connected to Rembertistraße and Rembertikirchhof by two gateways . The houses were between 8.50 and 9.50 meters high, about 5 meters wide and 6.50 meters deep and had their entrances to the courtyard. The "gatehouses" were about 1 meter higher.

In 1868 the 130-year-old Rembertikirche was demolished and replaced by Heinrich Müller from 1869 to 1871 with a building in neo-Gothic style. Between 1876 and 1878, a building was also built in the monastery courtyard, built by Heinrich Flügel: a two-story, 12.50 meter high central building - called the “castle” - with two side wings. In 1878 the monastery consisted of 45 houses with a total of 105 apartments. Most of these massive buildings are still preserved today.

The number of residents of the monastery increased further thanks to the expansion of the facility: in 1825 the facility had only 28 residents, in 1850 there were already 55. The composition of the residents also changed at the turn of the century: in 1825 54% of the residents were widows and 14% unmarried women, now more and more working women - especially teachers - came to the monastery. The proportion of men was very low at only 5% - today it is around 10%. Most of the Pröveners came from modest, but financially halfway secure backgrounds. The minimum entry age was 40 years. One of the well-known residents of the monastery at the end of the 19th century was the women's rights activist and writer Marie Mindermann , who lived in St. Remberti from 1856 to 1882.

The pen from the 20th century

From 1906 to 1907, the facility was expanded once more to include the three-storey “Kaiserhaus”, which stands a little apart from the Am Dobben . The building with a width of 21.30 meters, a depth of 11.50 meters and a height of 12.15 meters cost 141,000 marks. It was built by Eduard Gildemeister and Wilhelm Sunkel . The corresponding property originally belonged to the monastery farm yard. On the neighboring property on Rembertistraße, on which the large Remberti office building was later built, the Krudup family's associated old farm stood until 1908. The complete structural renovation of the monastery was completed with the installation of electric light in the 1910s.

The economic situation of the monastery was very good at the beginning of the 20th century. During the First World War and the Great Depression of the late 1920s to early 1930s, the pen's fortunes were greatly diminished. Many of the Pröveners were also at risk of poverty at that time and were dependent on food donations from the city's emergency and elderly aid.

During the Second World War , 9 houses of the monastery were seriously damaged and 3 partially damaged in bombing raids. In June 1942 the neighboring Rembertikirche burned down completely after being hit and the ruins had to be blown up. In May 1944, the legal foundation of the St. Remberti Stift was canceled at its own request and the institution was placed under the authority of the city. The assets were managed as special assets of the Senate, maintaining their previous purpose. Presumed reasons for this step were the foreseeable financial difficulties in a reconstruction and the feared takeover of the independent facility by the National Socialist People's Welfare . Towards the end of the war, numerous bombed-out families were housed in the monastery, at times up to 164 people were quartered in the 90 Pröveners.

During the war, the reconstruction of the damaged and burned-out buildings on the monastery grounds began, so that the main parts of the complex were restored by the end of the 1940s. After the damage was repaired, the monastery ran out of funds. In 1952, the purchase money was DM 2,700 for residents up to 50 years of age, and DM 1,500 for older people. However, the previous regulation no longer covered the financial needs of the facility in the long term and led to unjust distribution of costs depending on the residents' lifetime. Despite grants from the city, the facility's economic situation was critical. The attempt to retrospectively supplement the benefit contracts with a compensation for use in order to be able to collect additional funds failed. To remedy this, the almost 400 year old principle of shopping in the pen was finally abandoned in 1956 and converted into a monthly usage fee (similar to rent ).

In the 1960s, the Rembertiquartier was severely affected by large-scale infrastructure projects. The destroyed Rembertikirche was not rebuilt at its old location, but relocated to Schwachhauser Heerstraße to make room for the traffic junction of the Rembertikreisel and the planned (but not realized) " Mozart Route ".

Under the direction of Mayor and Senator Annemarie Mevissen , the independent St. Remberti Foundation was restored in 1971 and the buildings of the monastery were listed as a historical monument in 1973. From 1977 and 1986 the entire residential complex was completely renovated for 11 million DM according to plans by the architect Wilfried Turk . The renovation of the area was completed with the construction of the St. Remberti district house , a retirement and nursing home on the monastery grounds. For this purpose, some older residential buildings such as the "Muselius House" were demolished between Adlerstrasse and Hoppenbank .

The St.-Remberti-Stift today has around 100 apartments of various sizes - from 1½ to 4 rooms, with an area of 35 to 80 m². There are also 39 one-room and 18 two-room apartments in the district house , which is operated by the Bremer Heimstiftung .

See also

- Rimbert (830–888), from 865 to 888 Archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen

- St. Remberti (Bremen) , Protestant parish , separated from the monastery in 1596

- Remberti School , founded in 1596 and existing until 1970 by the St. Remberti community

Individual evidence

- ^ Ruprecht Grossmann, Heike Grossmann: The St. Remberti pen. Bremen's oldest social settlement through the ages . S. 11 .

- ↑ a b Ruprecht Grossmann, Heike Grossmann: The St. Remberti Stift. Bremen's oldest social settlement through the ages . S. 18th f .

- ↑ a b c Monument database of the LfD

- ^ Ruprecht Grossmann, Heike Grossmann: The St. Remberti pen. Bremen's oldest social settlement through the ages . S. 13 .

- ^ Diedrich Ehmck, Wilhelm von Bippen: Bremisches Urkundenbuch . tape 2 , p. 319 .

- ^ Ruprecht Grossmann, Heike Grossmann: The St. Remberti pen. Bremen's oldest social settlement through the ages . S. 23 .

- ^ Ruprecht Grossmann, Heike Grossmann: The St. Remberti pen. Bremen's oldest social settlement through the ages . S. 27 f .

- ^ Ruprecht Grossmann, Heike Grossmann: The St. Remberti pen. Bremen's oldest social settlement through the ages . S. 41 .

- ↑ a b Rudolf Stein: Bremen Baroque and Rococo . S. 98 .

- ^ Ruprecht Grossmann, Heike Grossmann: The St. Remberti pen. Bremen's oldest social settlement through the ages . S. 57 .

- ^ Ruprecht Grossmann, Heike Grossmann: The St. Remberti pen. Bremen's oldest social settlement through the ages . S. 54 .

- ^ Ruprecht Grossmann, Heike Grossmann: The St. Remberti pen. Bremen's oldest social settlement through the ages . S. 52 .

- ^ Johann Philipp Cassel: Historical news from the hospital or Präven St. Remberti before Bremen . S. 52 f .

- ^ Ruprecht Grossmann, Heike Grossmann: The St. Remberti pen. Bremen's oldest social settlement through the ages . S. 68 .

- ^ Rudolf Stein: Classicism and Romanticism in the architecture of Bremen . S. 126 .

- ^ Ruprecht Grossmann, Heike Grossmann: The St. Remberti pen. Bremen's oldest social settlement through the ages . S. 159 .

literature

- Ruprecht Grossmann, Heike Grossmann: The St.-Remberti-Stift. Bremen's oldest social settlement through the ages . Verlag M. Simmering , Lilienthal 1998, ISBN 3-927723-37-1 .

- Johann Philipp Cassel : Historical news from the hospital or Präven St. Remberti before Bremen . 1781.

- Diedrich Ehmck , Wilhelm von Bippen : Bremisches Urkundenbuch Vol. 2 No. 42 . Müller-Verlag, Bremen 1876, ISBN 978-3-927723-37-5 , p. 319.

- Rudolf Stein : Bremen Baroque and Rococo . Hauschild Verlag , Bremen 1960, pp. 96–98.

- Rudolf Stein: Classicism and Romanticism in the architecture of Bremen . Hauschild-Verlag, Bremen 1964, pp. 122–126.

Web links

- St. Remberti pen in the database of the State Office for Monument Preservation (LfD) Bremen.

- Website of the St. Remberti Parish

- Website of the Stadtteihaus St. Remberti of the Bremer Heimstiftung

Coordinates: 53 ° 4 '44.7 " N , 8 ° 49' 4.4" E