USS Triton (SSRN-586): Difference between revisions

Marcd30319 (talk | contribs) →Across the Pacific — to 7 March to 28 March: Rear_admiral_%28United_States%29#Rear_Admiral_.28upper_half.29 |

Marcd30319 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 191: | Line 191: | ||

==== Across the Pacific — to 7 March to 28 March==== |

==== Across the Pacific — to 7 March to 28 March==== |

||

On [[7 March]] [[1960]], ''Triton'' entered the [[Pacific Ocean]] and passed into the operational control of [[Rear_admiral_%28United_States%29#Rear_Admiral_.28upper_half.29|Rear Admiral]] [[Roy S. Benson]], [[COMSUBPAC|Commander Submarine Force U.S. Pacific Fleet (COMSUBPAC)]], who had been Captain Beach's commanding officer on the [[USS Trigger (SS-237|USS ''Trigger'']] during [[World War Two]]. ''Triton's'' first Pacific landfall was [[Easter Island]], some 2500 nautial miles (4630 km) away.<ref>First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-30 to B-31, B-33; Beach. ''Around the World Submerged'', p. 192</ref> |

On [[7 March]] [[1960]], ''Triton'' entered the [[Pacific Ocean]] and passed into the operational control of [[Rear_admiral_%28United_States%29#Rear_Admiral_.28upper_half.29|Rear Admiral]] [[Roy S. Benson]], [[COMSUBPAC|Commander Submarine Force U.S. Pacific Fleet (COMSUBPAC)]], who had been Captain Beach's commanding officer on the [[USS Trigger (SS-237)|USS ''Trigger'']] during [[World War Two]]. ''Triton's'' first Pacific landfall was [[Easter Island]], some 2500 nautial miles (4630 km) away.<ref>First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-30 to B-31, B-33; Beach. ''Around the World Submerged'', p. 192</ref> |

||

On [8 March]], ''Triton'' detected a seamount, registering a minumum depth of 350 fathoms (640 m), with a total height of 7000 feet (2134 m) above the ocean floor. Also on that day ,''Triton'' successfully conducted a drill stimulating the emergency shutdown of its reactors and loss of all power.<ref>First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-31 to B-33; Beach. ''Around the World Submerged'', p. 163-171</ref> |

On [8 March]], ''Triton'' detected a seamount, registering a minumum depth of 350 fathoms (640 m), with a total height of 7000 feet (2134 m) above the ocean floor. Also on that day ,''Triton'' successfully conducted a drill stimulating the emergency shutdown of its reactors and loss of all power.<ref>First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-31 to B-33; Beach. ''Around the World Submerged'', p. 163-171</ref> |

||

Revision as of 17:35, 18 March 2008

class="infobox" style="width:25.5em;border-spacing:2px;"

USS Triton (SSRN/SSN-586), a nuclear-powered radar picket submarine, was the first vessel to execute a submerged circumnavigation of the Earth which was accomplished during its shakedown cruise in early 1960.

At the time of her commissioning, Triton was the largest, most powerful submarine ever built, as well as being the only non-Soviet submarine to be powered by two nuclear reactors.

Triton was the second submarine and the fifth ship of the United States Navy to be named for Triton, a Greek demigod of the sea who was the son of Poseidon and Amphitrite.

Design History

Radar Picket Role

Radar-picket submarines were developed during the post-war period to provide intelligence information, electronic surveillance, and fighter aircraft interception control for forward-deployed naval forces. Unlike destroyers used as radar picket ships during World War Two, these submarines could avoid attack by submerging if detected. However, a key limiting factor was that these conventonally-powered submarines were too slow to operate with high-speed carrer task forces.[1]

Triton was designed in the mid-1950s as a radar picket submarine capable to operate at high speed, on the surface, in advance of an aircraft carrer task force. Triton's high speed was derived from her twin-reactor nuclear propulsion plant. On 27 September 1959, Triton achieved 30 knots (56 kph) during her initial sea trials.[2]

Triton's main air search radar was the AN/SPS-26, the U.S. Navy's first electronically scanned, three-deminsional search radar which was laboratory tested in 1953. The first set was installed onboard the destroyer leader USS Norfolk prior to its installation onboard the Triton in 1959.[3] The SPS-26 had a range of 65 nautical miles (120 km) and could track aircraft up to an altitude of 75,000 feet (22,866 m).[4] It was scanned electronically in elevation, and therefore did not need a separate height-finding radar.[5] The radar could be stowed in Triton's massive sail when not in use.

Triton had a separate air control compartment, located between its reactor and operations compartments, that housed a fully-staffed combat intelligence center (CIC) to process its radar, electronic, and air traffic data.

Twin Nuclear Reactor Propulsion Plant

To achieve the high speed required to meet her radar-picket mission, Triton was designed with two reactor propulsion plants. Triton was the only United States nuclear submarine ever to have been thus built. Her S4G reactors were identical sea-going versions to the land-based S3G reactor protoype.

As originally designed, Triton's total reactor output was rated at 34,000 horse power. However, Triton achieved 45,000 horsepower during her sea trials, and her first commanding officer, Captain Edward L. Beach, believed that Triton's plant could have reached 60,000 horsepower "had that been necessary."[6][7]

The number one reactor, located forward, supplied steam to the forward engineering room and the starboard propeller shaft. The number two reactor supplied steam to the after engineering room and the port propeller shaft. Each reactor could supply steam for the entire ship, or the reactors could be cross-connected as required.[8] It is the enhanced reliability, redundancy, and depedability of its dual-reactor plant offeref that was a key factor in the selection of Triton to undertake the first submeged circumnavigation of the world.[9]

Triton's dual-reactor plant served a number of operational and engineering objectives which continues to be a source of speculation and controversy to this day:

- Reliability Concerns — During the early 1950s, many engineers at Naval Reactors branch of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) were concerned about depending on single-reactor plants for submarine operations, particularly involving under-the-ice Arctic missions.[10]

- Surface Ship Testbed — The presence of two de-aerating feed tanks, which are used only on surface warship, suggests that Triton's twin-reactor plant served as a testbed for future multi-reactor surface warships.[11]

- Performance Optimization — The U.S. Navy was debating the best appoach to optimize performance, particularly underwater speed. Triton represented sheer brute horsepower to achieve higher speeds, while the other approached emphasized the more hydrodynamic teardrop-shaped hull-form pioneered by the USS Albacore and, when combined with nuclear power, the USS Skipjack to achieve higher speed with less horsepower.[12]

Finally, Triton's twin-reactor plant posed an number of major technical issues which delayed her eventual disposal for years.[13]

Other Design Features

Triton featured a knife-like bow and a high reserve buoyancy (30%) provided by 22 ballast tanks, the most ever installed on an American submarine.[14] She was the last submarine to have a conning tower (a water-tight compartment built into the sail), as well as the last American submarine to have twin screws or a stern torpedo room. Until the commissioning of the Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines, Triton was the longest submarine ever built by the Navy.

Combat Systems

- AN/BQS-4 — This active/passive sonar detecting-ranging set had a listening range up to 20 nautical miles (37 km) for surfaced or snorkling submarines, optimized to to 35 nautical miles (65 km) with target tracking capility within 5 degrees of accuracy.[15]

- AN/BQR-2 — This hull-mounted passive sonar array supplemneted the BQS-4 system, with a range up en nautical miles (18.5 km) and a bearig accuracy of 1/10th of degree, allowing the BQR-2 to be used for fire contol in torpedo attacks.[16]

- MK-101 — Fire-control system.[17]

Construction History

Keel Laying

Triton was authorized under the U.S. Department of Defense appropriation for Fiscal Year 1956 as SCB 132.[18] Her keel was laid down on 29 May 1956 in Groton, Connecticut, by the Electric Boat Division of the General Dynamics Corporation.

Electric Boat built the Triton using material supplied by 739 different companies during the ensuing 26 months of construction following her keel-laying.[19]

Triton's length presented Electric Boat with many problems during her construction. She was so long that her bow obstructed the slipways railway facility used for transporting material around the yard, so the lower half of her bow was cut away and re-attached just days prior to her launch. Similarly, the last 50 feet (15 m) of her stern had to be built on an adjoining slipway and added before she was launched. Her sail was found to be too high to go under the scaffolding, so the top 12 feet (4 m) of the sail were cut away and re-attached later.[20]

Launching

Triton was launched on 19 August 1958, with Louise Will, the wife of Vice Admiral John Will USN (ref.), as its sponsor. The principal address was delivered by Admiral Jerauld Wright, the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANTFLT) and Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT) for NATO.[21] Over 35,000 guests attened the launchng, the largest crowd to to witness a submarine launching up to that time.[22]

Triton would meet several key milestones before her commissioning, as listed below in chronological order:

- Reactor No. 2 achieved intitial critical mass — 8 February 1959

- Reactor No. 1 achieved intitial critical mass — 3 April 1959

- Initial Sea Trial — 27 September 1959

- Preiminary Acceptance Trials (PAT) — 20 October - 23 October 1959

Two shipboard accidents occurred during Triton's post-launch fitting out:

- 2 October 1958 — A steam valve failed during testing, causing a large cloud of steam that filled the compartment.

- 7 April 1959 — A fire broke out during the testing of a deep-fat fryer which spread from the galley into the ventilation lines of the crew's mess.

Both incidents, neither nuclear related, were quickly handled by ship personnel, with Lt. Commander Leslie B. Kelly, the prospective chief engineering officer, being awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for his quick action during the 2 October incident.[23]

Commissioning

Triton was commissioned on 10 November 1959 with Captain Edward L. Beach, Jr. in command. The keynote address was given by Vice Admiral Bernard L. Austin, the Deputy CNO for Plans and Policy, who noted:

As the largest submarine ever built, her performance will be carefully followed by naval designers and planners the world over. For many years strategists have speculated on the possibilities of tankers, cargo ships and transports that could navigate under water. Some of our more futuristic dreamers have talked of whole fleets that submerge. Triton is a bold venture into this field.[24]

A water color painting of the ship was presented by the American Water Color Society, and the original ship's bell for the first submarine Triton was donated by the widow of the late Rear Admiral Willis Lent, the first skipper of that ship.[25]

The final cost of building Triton, less its reactors, nuclear fuel, and other related costs paid by the AEC, was $109,000,000 USD, making Triton the mst expensive submarine built at the time of her commissioning.[26]

Triton was assigned to Submarine Squadron 10, the U.S. Navy's first all-nuclear force, based at the U.S. Submaine Base in New London, Connecticut, under the command of Commodore Tom Henry.

Triton subsequently completed torpedo trials at Naval Station Newport and conducted other special tests at the Norfolk Navy Base before returning to Electric Boat on 7 December 1959 in order to install special communications equipment. Work on the Triton at Electric Boat was delayed as priority was given to completing the Navy's first two fleet ballistic missile (FBM) submarines, the George Washington and the Patrick Henry.

On 20 January 1960, Triton got underway to conduct an accelerated series of at-sea testing. Triton returned on 1 February as preparations continued for her forthcoming shakedown cruise, scheduled for departure on 16 February 1960, which involved operating with the command ship USS Northampton (CLC-1), the flagship of the U.S. Second Fleet, in northern European waters.

On 1 February 1960, Captain Beach received a messge from Rear Admiral Lawrence R. Daspit, Commander Submarines Atlantic Fleet (COMSUBLANT), instructing Beach to attend a top secret meeting at the Pentagon on 4 February.[27]

Mission Objectives

On 4 February 1960, Captain Edward L. Beach and Commodore Tom Henry of Submarine Squadron 10 arrived at the Pentagon in civilian dress to attend a top-secret, high-level meeting with the following individuals:

- Vice Admiral Wallace M. Beakley, Deputy CNO for Fleet Operations and Readiness

- Rear Admiral Lawson P. Ramage, Director, Undersea Warfare Division, OPNAV

- Captain Henry G. Munson, Director, U.S. Navy Hydrographic Office

- Representatives from COMSUBLANT and COMSUBPAC

It was announced that Triton's upcoming shakedown cruise was to be a submerged world circumnavigation, code-named Operation Sandblast, with the following mission objectives:

- For purposes of geophysical and oceanographic research and to determine habitability, endurance and psychological stress - all extremely important to the Polaris program - it had been decided that a rapid round-the-world trip, touching the areas of interest, should be conducted. Maximum stability of the observing platorm and unbroken continuity around the world were important. Additionally, for reasons of the national interest it had been decided that the voyage should be made entirely submerged undetected by our own or other forces and completed as soon as possible. TRITON, because of her size, speed and extra dependability of her two-reactor plant, had been chosen for the mission.

Triton would generally follow the track of the first circumnavigation (1519–1522) led by Ferdinand Magellan, departing 16 February, as scheduled, and arriving back home no later than 10 May 1960.

Beach and Henry arrived back in New London at 5:45 A.M. on 5 February. Later that morning, after breakfast, Beach briefed his officers, whom Beach had insisted needed to know, about their new shakedown orders and the mission objectives for Operation Sandblast.[28]

Mission Preparations

The officers and crew of the USS Triton had just 12 days to complete preparations for their much more ambitious, but top secret shakedown cruise. Except for one exception, the enlisted personnel did not know the true nature of their upcoming mission. The following personel also joined Triton for her shakedown cruise, with none aware of the top-secret nature of Operation Sandblast:

- Commander Joseph Baynor Roberts, USNR, from the U.S. Navy of Information

- Dr. Benjamin B. Weybrew, psychologist from the U.S Naval Submarine Medical Research Laboratory

- Michael Smalet, geophysicist from the U.S. Navy Hydrographic Office

- Gordon E. Wilkes, civil engineer from the U.S. Navy Hydrographic Office

- Nicholas R. Mabry, oceanographer from from the U.S. Navy Hydrographic Office

- Eldon C. Good from the Sperry Gyroscopic Company, Inertial Navigation Division

- Frank E. McConnell, engineer, General Dynamics, Electric Boat Division

- First Class Photographer's Mate (PH1) William R. Hadley, USN, detached from Naval Air Forces, U.S. Atlantic Fleet

Commander Roberts is the well-known photographer from the National Geographic Magazine, and he was recalled to active duty to serve as the press pool for the voyage. Also, he and PH1 Hadley would coordinate the photo-reconnaissance aspects of Operation Sandblast. Smalet, Wilkes, and Mabry would coordinate the various scientific and technical aspects of Operation Sandblast for the U.S. Navy's Hydrographic Office. Good would monitor the Ship Inertial Navigation System (SINS) prototype newly installed onboard Triton. McConnell was the Electric Boat guaranty representative assigned to Triton's shakedown cruise.[29]

A cover story was devised that, following the shakedown cruise, Triton would proceed to the Caribbean Sea to undergo addtional testing required by the Bureau of Ships. The crew and civilians were instructed to file their Federal income taxes early and take care of all other personal finances that may arise through mid-May.[30]

Lt. Commander Will M. Adams, Triton's executive officer, and Lt. Commander Robert W. Bulmer, Triton's operations officer, prepared the precise, mile-by-mile track of their upcoming voyage at the secure chart room, located at COMSUBLANT headquarters, with Chief Quartermaster (QMC) William J. Marshall, the only non-officer to know about Operation Sandblast prior the ship's departure.[31]

Lt. Commander Robert D. Fisher, Triton's supply officer, coordinated the loading of ship's stores sufficient for a 120-day voyage. Eventually, some 77,613 pounds (35,205 kg) of food was loaded onboard, including 16,487 pounds (7,478 kg) of frozen food, 6,631 pounds (3,009 kg) of canned meat, 1,300 pounds (590 kg) of coffee, and 1,285 pounds (583 kg) of potatoes.[32]

Vice Admiral Hyman G. Rickover sent special power-setting instructions for Triton's reactors, allowing them to operate with greater flexibility and a higher safety factor.[33] On 15 February 1960, Triton went to sea to do a final check of all shipboard equipment. Except for a malfunctioning wave-motion sensor, Triton was ready for her shakedown cruise, set for 16 February.[34]

Around the World Submerged — 1960

Outward Bound — 16 February to 24 February

Triton departed New London on 16 February 1960 for what was announced as her shakedown cruise. Her crew had been told to prepare for a longer than normal voyage. Triton shaped course to the south-east(134 degrees True).

At dawn on 17 February, Triton performed its first morning star-sighting using the built-in sextantusing using its No. 1 periscope during its daily ventilaion of its shipboard atmosphere. The inboard induction valve was closed after the removal of a rusted flashlight that had prevented its closure.[35]

Captain Edward L. Beach announced the true nature of their shakedown cruise:

- Men, I know you’ve all been waiting to learn what this cruise is about, and why we’re still headed southeast. Now, at last, I can tell you that we are going on the voyage which all submariners have dreamed of ever since they possessed the means of doing so. We have the ship and we have the crew. We’re going around the world, nonstop. And we’re going to do it entirely submerged.[36]

Later that day, Triton experienced a serious leak with a main condenser circulating water pump and a reactor warning alarm tripped because of a defective electical connection. Both incidents were handled successfully and did not affect the ship's performance.[37]

On 18 February, Triton conducted its first general daily drill and, on 19 February, released its first twice-daily hydrographic bottle used to study ocean current patterns.[38]

On 23 February, Triton detected a previously uncharted seamount with its echo-sounding fathometer.[39]

Triton made its first landfall, reaching St. Peter and Paul Rocks on 24 February after travelling 3250 naultical miles (6019 km}. The Rocks would serve as home plate for Triton's submerged crcumnavigation. Photographic reconnaissance was carried out by Lt. Richard M. Harris, the CIC/ECM officer, and Chief Cryptologic Technician (CTC) William R. Hadley, who the ship's secondary photo-recon team for the voyage. Triton turned south and crossed the equator for the first time later that day, passing into the Southern Hemisphere, with ship's personnel participating in the crossing the line ceremony.[40]

Destination: Cape Horn — 24 Feruary to 7 March

On 1 March 1960, as Triton passed along the east coast of South America, a trio of crises threatened to end Operaton Sandblast:

- Chief Radarman (RDCA) John R. Poole began suffering from a series of kidney stones.

- The ship's fathometer malfunctioned, putting it out of commission, with its loss meaning Triton could no longer echo-sound the sea floor, risking possible grounding or collision.

- Readings on one of the reactors indicated a serious malfunction which require its shutdown.

As Captain Beach noted: " So far as Triton and the first of March were concerned, it seemed that troubles were not confined to pairs. On that day we were to have them in threes."[41]

Later that day, Lt. Milton R. Rubb and his electronics technicians returned the fathometer to operational status, as did Chief Engineer Donald D. Fears, Reactor Officer Robert P.McDonald, and Triton's engineering crew regarding the reactor in question. Since Poole's symptoms were interrmittent, Triton continued south, although there was a detour when the ship investigated an unknown sonar contact that turned out to be a school of fish.[42]

On 3 March, Triton raised the Falkland Islands on radar and prepared to conduct photoreconnaissance of Port Stanley, but before they could sight the islands, Poole's condition worsened so, taking a calculated risk, Captain Beach ordered Triton's course reversed, ran up all ahead Flank, and sent a radio message describing the situation.[43] From the ship's log on that date:

- In the control and living spaces, the ship had quieted down, too. Orders were given in low voices; the men speak to each oher, carrying out their normal duties, in a repressed atmosphere. A regular pall has descended upon us. I know that all hands are aware of the decision and recognize the need for it. Perhaps they are relieved that they did not have to make it. But it is apparent that this unexpected illness, something that could neither have been foreseen nor prevented, may ruin our submergence record.[44]

In the early hours of 5 March, Triton rendezvoused with the heavy cruiser Macon (CA-132) off Montevideo, Uruguay, after a diversion of over 2000 nautical miles (3706 km). That broaching was the only time Triton would surface during the circumnavigation, and a line-handling party led by Lt. George A. Sawyer, the ship's gunnery officer trasferred Poole to the waiting whale boat. Poole would be the only crew member who did not complete the voyage.[45]

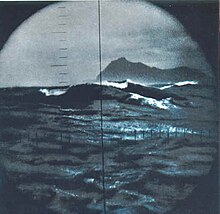

Returning south, Triton passed to the west of the Falklands, and rounded Cape Horn through Estrecho de le Maire on 7 March. Captain Beach described his first impressions of this legendary lands-end of the Western Hemisphere as being "bold and forbidding, like the sway-backed profile of some prehsitoric sea onster."[46] Captain Beach allowed all crew members the opportunity to view the Horn through the periscope, requiring five reverses of course to keep it in sight.[47]

Across the Pacific — to 7 March to 28 March

On 7 March 1960, Triton entered the Pacific Ocean and passed into the operational control of Rear Admiral Roy S. Benson, Commander Submarine Force U.S. Pacific Fleet (COMSUBPAC), who had been Captain Beach's commanding officer on the USS Trigger during World War Two. Triton's first Pacific landfall was Easter Island, some 2500 nautial miles (4630 km) away.[48]

On [8 March]], Triton detected a seamount, registering a minumum depth of 350 fathoms (640 m), with a total height of 7000 feet (2134 m) above the ocean floor. Also on that day ,Triton successfully conducted a drill stimulating the emergency shutdown of its reactors and loss of all power.[49]

On 9 March, the starboard shaft seal sprung a major leak in the after engine room. A make-shift locking clamp was jury-rigged to contain the leak.[50]

On 12 March, the trouble-plagued fathometer ceased operation when its transducer header flooded, grounding out the entire system. Since the transducer head was located outside the ship's pressure hull, it could not be repaired except in drydock. Without an operational fathometer, Triton could be vulnerable to grounding or collision with uncharted submerged formations.

An alternative to the fathometer was devised invovling the uses of the ship's active forward search sonar with the gravity meter installed in the combat intelligence center (CIC). By using both systems in tandem, underwater masses could be detected and avoided, although this approached lacked the capability of the fathometer to echo-sound the depth of the ocean floor.[51]

On 13 March, Triton detected a submerged peak using active sonar and the gravity meter that confirm the feasibility of this procedure.[52]

Triton next raised Easter Island on 13 March, first by radar, then by periscope. She photographed the northeastern coast for some two and a half hours before spotting the statue Thor Heyerdahl had erected. Again all crewmen were invited to observe through the periscope. Triton's next landfall is Guam, some 6734 nautical miles (12,471 km)[53]

On 19 March Triton crossed the equator for the second time and passsed into the Northern Hemisphere.

On 23 March Triton crossed the International Date Line and lost 24 March from her calendar.

On 27 March she passed the point of closest approach to the location where the previous Triton was lost during World War II, and a memorial service was held to commemorate the occasion. A submerged naval gun salute was fired to honor the lost crew when three water-slugs were shot in quick succession from the forward torpedo tubes.

On the morning of 28 March Triton raised Guam and observed activity on shore. Petty Officer Edward Carbullido, who had been born on Guam but had not returned home for 14 years, was asked to identify his parents' house through the periscope while the boat remained submerged in Agat Bay.

In the Wake of Magellan

On 31 March, Triton passed from the Philippine Sea through the Surigao Strait into the Mindanao Sea, then through the Bohol Strait into the Camotes Sea. On 1 April, she raised Mactan Island and shortly before noon sighted the monument commemorating the death of Ferdinand Magellan at that site, and was in turn sighted by the only unauthorized person to spot the submarine during her secret voyage — a young Filipino man in a small dugout canoe about 50 yards off Triton’s beam, later identified as nineteen-year-old Rufino Baring. That afternoon, Triton proceeded through Hilutangan Channel into the Sulu Sea.

Triton proceeded through the Sibutu Passage into the Celebes Sea on 2 April.

On 3 April, Triton entered the Makassar Strait, crossing the equator for the third time, transiting the Flores Sea during 4 April.

Indian Ocean

On 5 April Triton entered the Indian Ocean via the Lombok Strait. The transition was dramatically sharp as the change in salinity and density of the seawater caused a depth excursion: Triton abruptly dove from periscope depth to 125 feet in about 40 seconds. While crossing the Indian Ocean, Triton conducted an experiment: beginning on 10 April, rather than refreshing the air in the boat by snorkeling each night, she remained sealed, using compressed air to make up for consumed oxygen, and in addition on 15 April, the smoking lamp was extinguished — no tobacco smoking was permitted anywhere aboard.

On Easter Sunday, 17 April, Triton rounded the Cape of Good Hope and entered the South Atlantic Ocean.

Return to the Rocks

The smoking lamp was relighted on 18 April, the three days of prohibition having taken a noticeable toll on the crew's morale. Rather than passing the word in a tradition manner, Captain Beach demonstrated the lifting of the ban by walking though the boat smoking a cigar, blowing smoke in people's faces, and asking them "don't you wish you could do this?" He recorded in his log that "it took some 37 seconds for the word to get around." On 20 April, Triton crossed the Prime Meridian, and on 24 April, the sealed atmosphere experiment was terminated.

On 25 April, Triton crossed the equator for the final time, and shortly thereafter, sighted St. Peter and Paul Rocks were sighted, completing the first submergedcircumnavigation.

Homeward Bound

Triton proceeded to Tenerife in the Canary Islands where she arrived on 30 April, and thereafter setting course for Cadiz to complete another mission, the delivery of a plaque created on board the boat for this purpose (see below).

Triton returned to the United States, surfacing off the coast of Delaware on 10 May, and arrived back at Groton, Connecticut, later that day, completing the first submerged circumnavigation of the earth.

Mission Accomplishments

Key Figures[54]

- Triton traveled over 35,979 nautical miles (41,411 statute miles, or 66,645 kilometers) submerged, over 84 days, 19 hours, and 8 minutes, between 16 February and 10 May, 1960.

- The actual circumnavigation occurred between 24 February and 25 April 1960, with a submerged track of 26,723 nautical miles (30,752 statute miles, or 49,491 kilometers), traversed in 60 days and 21 hours, at an average speed of over 18 knots (21 mph, or 33 kph).

- Triton crossed the equator four times during its circumnavigation.

Scientific Accomplishments

Triton conducted numerous scientific experiments, including taking water samples; making gravity measurements; releasing hydrographic bottles to track ocean currents; and conducting underwater soundings to map seamounts, coral reefs, and other submerged topographic structures.

Vital National Interests

Triton's circumnavigation proved nuclear-powered submarines could undertake extended operations independent of any external support.

Triton tested a prototype ship inertial navigational system (SINS) for submarine use, as well as being the first submarine to test the floating very low frequency (VLF) communications buoy system, with both systems being vital for the Navy's upcoming Polaris fleet ballistic missile submarines (FBM) deterrence patrols.

The psychological testing of its crew members to determine the effects of long-term isolation was particularly relevant for the initial deployment of the Navy's fleet ballistic missile submarines, as well as NASA's upcoming manned space program, Project Mercury.[55]

Aftermath

Because of the public uproar over the U-2 Incident, most of the official celebrations for Triton's submerged circumnavigation were cancelled. The voyage did receive extensive contemporary coverage by the news media, including feature mgaazine articles by Argosy, Life, Look, and National Geographic, as well as television and newsreels.[56]

On 10 May 1960, Triton received the Presidential Unit Citation (PUC) from United States Secretary of the Navy William B. Franke, which was accepted by Chief Torpedoman's Mate (TMC) Raymond Chester Fitzjarrald, the chief of the boat (COB), on behalf of the officers and crew of the Triton. This was only the second time that a naval vessels was awarded the PUC for a peacetime mission. SecNav Franke also presented the U.S. Navy Commendation Ribbon to Torpedoman's Mate Third Class (TM3) Allen W. Steele for his quick and decisive actions in handling a serious hydraulic oil leak that occurred in the aft torpedo room on 24 April 1960[57]

Captain Edward L. Beach received the Legion of Merit from President of the United States Dwight D. Eisenhower at the White House on May 10th. He also received the 1960 Giant of Adventure Award from the popular men's magazine Argosy, which dubbed Beach the "Magellan of the Deep."[58] In 1961, the American Philosophical Society presented Captain Beach with its Magellanic Premium, the nation's oldest and most prestigious scientific award, in "recognition of his navigation of the U.S. submarine Triton around the globe."[59]

Captain Beach wrote the lead article (“Triton Follows Magellan's Wake”) on the Triton's circumnavigation of the November 1960 issue of National Geographic Magazine (Vol. 118, No. 5).

Operational History

Initial Deployment

Following her post-shakedown availability, Triton deployed to European waters with the Second Fleet to participate in NATO exercises against Brtish naval forces led by the aircraft carriers Ark Royal and Hermes under the command of Rear Admiral Sir Charles Madden. Triton climaxed the deployment with a port visit to Bremerhaven, West Germany, the first visit by a nuclear-powered ship to a European port.[60]

Overhaul and Conversion

For the first half of 1961, Triton conducted operational patrols and training exercises with the Atlantic Fleet. During this period, the rising threat posed by Soviet submarine forces increased the Navy's demands for nuclear-powered attack submarines with antisubmarine warfare (ASW) capability. Accordingly, upon the demise of the Navy's radar picket submarine program, Triton was redesignated to hull classification symbol SSN-586 on 1 March 1961 and entered the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in June 1962 for conversion to an attack submarine. Her crew complement was reduced from 172 men to 159. The Navy had no plans to use her radar picket capability, but she still carried her BPS-2 search radar and could have fulfilled this role. She was overhauled and refueling at Groton, Connecticut, from September 1962 to January 1964.

Subsequent Operations

In March 1964, upon completion of this overhaul, Triton's home port was changed from New London, Connecticut, to Norfolk, Virginia. On 13 April 1964, Triton became the flagship for the Submarine Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, and served in that role until relieved by submarine Ray (SSN-653) on 1 June 1967. Eleven days later, Triton was shifted to her original home port of New London.

Decommissioning

Because of cutbacks in defense spending, Triton's scheduled 1967 overhaul was cancelled, and the submarine — along with 60 other vessels — was slated for inactivation. From October 1968 through May 1969, the submarine underwent preservation and inactivation processes, and Triton was decommissioned on 3 May 1969.

Triton became th first U.S. nuclear-powered submarine to be taken out of service, although the Soviet Navy's November-class submarine K-27, equipped with two liquid metal (lead-bismuth) cooled VT-1 reactors, had been deactivated by 20 July 1968.[61]

Commanding Officers

- Edward L. Beach — November 1959 to Juy 1961

- George Morin — July 1961 to September 1964

- Robert Rawlins — September 1964 to November 1966.

- Frank Wadsworth — November 1966 to May 1969

Awards and Commendations

Presidential Unit Citation

Citation:

- For meritorious achievement from the 16th of February 1960 to the 10th of May 1960.

- During this period TRITON circumnavigated the earth submerged, generally following the route of Magellan’s historic voyage. In addition to proving the ability of both crew and nuclear submarine to accomplish a mission which required almost three months of submergence, TRITON collected much data of scientific importance. The performance, determination and devotion to duty of TRITON’s crew were in keeping with the highest traditions of the naval service.

- All members of the crew who made this voyage are authorized to wear the Presidential Unit Citation ribbon with a special clasp in the form of a golden replica of the globe.[62]

The White House – May 10, 1960

Citation:

- For exceptionally meritorious service during a period in 1967, USS TRITON, a nuclear submarine, conducted an important and arduous independent submarine operation of great importance to the national defense of the United States. The outstanding results during this operation attests to the professional skill, resourcefulness, and ingenuity of TRITON’s officers and men. Their inspiring performance of duty is in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.[63]

Secretary of the Navy – 1967

Final Deposition

On 6 May 1969, Triton departed New London under tow and proceeded to Norfolk where she was placed in the inactive fleet. She remained berthed at Norfolk or at the St. Julien's Creek Annex of Norfolk Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth, Virginia into at least 1991, although she was only stricken on 30 April 1986 from the Naval Vessel Registry.

The hulk of Ex-Triton was eventually berthed in the Bremerton Naval Shipyard, Bremerton, Washington, to await her turn through the Nuclear Powered Ship and Submarine Recycling Program.

Beginning in June 2007, Ex-Triton made preparations for entering drydock for recycling. Ex-Triton landed on the keel resting blocks in the drydock basin in October of 2007.[64][65]

Cultural References

Antigua-Barbuda issued a stamp commerating Triton's 1960 submerged circumnaviation (see image). Triton was also referenced briefly in three popular Cold War novels:

- The Last Mayday by Keith Wheeler (1968) depicts Triton participating in a submarine training exercise at the beginning of the novel, with spedial notice made of her large, rectangular sail.

- Cold is the Sea by Edward L. Beach, the 1978 sequel to his 1955 best-seller Run Silent, Run Deep, mentions Triton several times.

- The Hunt for Red October by Tom Clancy (1984) mentions, as biographical background, that the Charlie-class submarine commanded by Marko Ramius "hounded mercilessly for twelve hours" the Triton in the Norwegian Sea . Subsequently, Raimius "would note with no small satisfaction that the Triton was soon thereafter retired, because, it was said, the oversized vessel had proven unable to deal with the newer Soviet designs."

Finally, Triton was the name of one of the submersibles used in the Submarine Voyage attraction at Disneyland which operated from 1959 to 1998.

Legacy

The sea may yet hold the key to the salvation of man and his civilization. That the world may better understand this, the Navy directed a submerged retrace of Ferdinand Magellan's historic circumnavigation. The honor of doing it fell to Triton, but it it has been a national accomplishment; for the sinews and the power which make up our ship, the genius which designed her, the thousands and hundreds of thousands who labored, each at his own metier, in all parts of the country, to build her safe, strong, self-reliant, are America. Triton, a unit of their Navy, pridefully and respectfully dedicates this voyage to the people of the United States.[66]

— Captain Edward L. Beach, Jr., U.S. Navy (2 May 1960)

Triton Plaque

In the eight days prior to Triton's departure on its around-the-world submerged voyage, Captain Edward L. Beach approached Lt. Tom B. Thamm, Triton's Auxiliary Division Officer, to design a commemorative plague for their upcoming voyage as well as the first circumnavigation of the world led by Ferdinand Magellan.[67]

The plaque's eventual design consisted of a brass disk about 23 inches (58.5 cm) in diameter, bearing a sailing ship reminiscent of Ferdinand Magellan's carrack Trinidad above the US submarine dolphin insignia with the years 1519 and 1960 between them, all within a laurel wreath. Outside the wreath is the motto AVE NOBILIS DUX, ITERUM FACTUM EST ("Hail Noble Captain, It Is Done Again").[68]

Commodore Tom Henry of Submarine Squadron 10 supervised the completion of the plaque. The carving of the wooden form was done by retired Chief Electrician's Mate Ernest L. Benson at the New London Submarine Base. The actual molding of the plaque was done by the Mystic Foundry.[69]

During the homeward leg of its around-the-world voyage, Triton rendevous with the destroyer USS John W. Weeks (DD-701) on 2 May 1960 off Cadiz, Spain, the departure point for Magellan's eartlier voyage. Triton broached, and the Weeks transferred the finished plaque to the Triton for transport back to the United States. The Triton plaque was subsequently presented to the Spanish government by John Davis Lodge, the United States Ambassador to Spain.[70]

Copies of the Triton Plaque are at the following locations:

- City Hall — Sanlucar de Barrameda, Spain

- Mystic Seaport Museum — Mystic, Connecticut

- Naval Historical Association — Washington, DC

- U.S. Navy Submarine School — Groton, Connecticut

- U.S. Navy Submarine Force Museum and Library — Groton, Connecticut

The plaque mounted on the wall of the city hall of Sanlucar de Barrameda also has a marble slab memorializing the 1960 Triton submerged circumnavigation.

Triton Medal

The Triton Medal is a special commemorative heirloom of the 1960 around-the-world voyage by the Triton. It was presented to each member of the Circumnavigation Crew by Captain Edward L. Beach, who had the medals cast in Bremerhaven, West Germany when the Triton visited that port following her first overseas deployment during the Fall of 1960.[71]

On the face of the medal is a clear anchor with three electron rings circling the shank. The name of each recipient is engraved below the anchor crown. Around the circumference of the medal's face is the inscription, "FIRST SUBMERGED CIRCUMNAVIGATION OF THE WORLD" and "USS TRITON SSRN 586 1960". The edge of the medal's face is encircled by rope. On the reverse of the medal is a miniature replica of the Triton Plaque.[72]

Triton Light

The crew of the Triton provided samples of water taken from the 22 seas through which their ship had passed during their submerged circumnavigation, which were used to fill a globe built into the Triton Light along with a commemorative marker.[73]

Triton Hall

The U.S. Navy dedicated the USS Triton Recruit Barracks at its Recruit Training Command (RTC) located at the Naval Station Great Lakes near North Chicago, Illinois on 25 June 2004, which honors the memory of two submarines named Triton and includes memorability from both vessels. Guest speakers included:

- Captain Robert Rawlins, USN (ret.), who commanded the nuclear submarine Triton from September 1964 to November 1966

- Jeanine McKenzie Allen, a researcher on the history of both submarines

- Admiral Henry G. Chiles Jr., USN (ret.), who was the first naval officer to command the U.S. Strategic Command

Triton Hall is the fifth barracks constructed under the RTC Recapitalization Project and covers 172,000 square feet (15,979 square meters). The facility is designed to accommodate 1056 recruits and includes berthing, classrooms, learning resource centers, a galley, a quarterdeck, and a modern HVAC system.[74]

Triton Park

Triton's massive sail superstructure is set to be preserved as the centerpiece for a future memorial park along the Columbia River The park's tentative location is at the end of Port of Benton Boulevard in north Richland, Washington, with a target date of Fall 2009 for the start of contruction.[75]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Cold War Curiousities: U.S. Radar Picket Submarines - Article from Undersea Warfare Magazine, Winter/Spring 2002, Vol 4, No 2

- ^ Polmar and Moore. Cold War Submarines, p. 67

- ^ Norman Polmar, The Naval Institute Guide to the Ships and Aircraft of the U.S. Fleet, 15th ed., p. 527

- ^ Polmar and Moore. Cold War Submarines, p. 67

- ^ Cold War Curiousities: U.S. Radar Picket Submarines - Article from Undersea Warfare Magazine, Winter/Spring 2002, Vol 4, No 2

- ^ Ship's History @ Unofficial USS Triton website

- ^ Polmar and Moore. Cold War Submarines, p. 67

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged. p. 2

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-5

- ^ Polmar and Moore. Cold War Submarines, p. 65, 68

- ^ Beach. Salt and Steel, p. 263

- ^ See "USS Triton: The Ultimate Submersible" by Largess and Horwits

- ^ posting dated 2/15/2008, 3:07 am Triton Message Board

- ^ Polmar and Moore. Cold War Submarines, p. 67

- ^ Polmar and Moore. Cold War Submarines, p. 18

- ^ Polmar and Moore. Cold War Submarines, p. 18

- ^ Ship's History @ Unofficial USS Triton website

- ^ Norman Polmar, The Naval Institute Guide to the Ships and Aircraft of the U.S. Fleet, 15th ed., Appendix C

- ^ Ship's History @ Unofficial USS Triton website

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p.4 - 6

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 6 - 9

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-1

- ^ Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-1 to B-2; Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 12 - 14

- ^ Polmar and Moore. Cold War Submarines, p. 67

- ^ Beach. Around the Word Submerged, p. 39 - 40

- ^ Polmar and Moore. Cold War Submarine, p. 67

- ^ Beach. Around the Word Submerged, p. 40 - 42; First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-5

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. ix - x, Chapter 3, p. 50 - 51; First Submerged Cicumnavigation 1960, B-5 to B-6, B-20

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. ix - x, Chapter 3, p. 50 - 51; First Submerged Cicumnavigation 1960, B-5 to B-6, B-20

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p 47- 48, 56; First Submerged Cicumnavigation 1960, B-5 to B-6

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 50

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 52 - 53

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 51 - 52

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 56 - 57

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-7 to B-9; Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 84-87

- ^ Beach. Around the Word Submerged, p. 89-92

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 93-95

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-9 to B-10

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-12; Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 100-102

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-17 to B-17; Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 102-112

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 128

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-22 to B-23; Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 116-140

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-24 to B-26; Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 116-140

- ^ Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-25

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-26 to B-30; Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 142-158

- ^ "Triton Follows Magellan's Wake," p. 593

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-30 to B-31; Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 159-162

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-30 to B-31, B-33; Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 192

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-31 to B-33; Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 163-171

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 171-175

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 175-179

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-33; Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 175-179

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-33 to B-35; Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 179-180

- ^ Beach, Around the World Submerged, appendice

- ^ Beach, "Triton Follows Magellan's Wake," National Geographic Magazine, p. 614 - 615

- ^ "New Magellan: Triton Circles World Submerged" {12 May 1960) Universal Newsreel narrated by Ed Herlihy

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 254 - 257, 284

- ^ "Magellan of the Deep" Argosy, August 1960

- ^ The Magellanic Premium of the American Philosophical Society

- ^ Edward L. Beach. Salt and Steel, p. 263 - 269

- ^ Polmar and Moore. Cold War Submarines, p. 68, 81

- ^ Citation Presidential Unit Citation for making the first submerged circumnavigation of the world.

- ^ Citation Naval Unit Citation (1967).

- ^ Posting dated 6/9/2007, 4:26 pm. Triton Message Board

- ^ Posting dated 10/13/2007, 9:30 pm Triton Message Board

- ^ First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960, B-79

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 55-56, 290

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 55-56, 290; Around The World Submerged - The Triton Plaque - Unofficial USS Triton web site

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 55-56, 290

- ^ Beach. Around the World Submerged, p. 263-267, 290

- ^ Around The World Submerged - The Triton Medal - Unofficial USS Triton web site

- ^ Around The World Submerged - The Triton Medal - Unofficial USS Triton web site

- ^ Triton Light Pictures

- ^ Dedication Ceremony - USS Triton Recruit Barracks program dated Friday, June 25th, 2004

- ^ Posting dated 9/21/2007, 8:19 pm Triton Message Board; "Nuclear Sub Coming to New Richland Park" - KNDO/KNDU - Washington, February 21, 2008 @ 12:02 PM EST

References

Primary Sources

- USS Triton SSRN 586 First Submerged Circumnavigation 1960. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1960. {O - 550280}.

- Papers of Vice Admiral Wallace M. Beakley, Operational Archives Branch, Naval Historical Center, Washington, D.C.

Secondary Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

- Beach, Edward L. (1962). Around the World Submerged: The Voyage of the Triton (first edition ed.). New York / Chicago / San Francisco: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. LCC 62-18406.

AVE NOBLIS DUX ITERUM FACTUM EST

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)

- Beach, Edward L. "Triton Follows Magellan's Wake". National Geographic Magazine, November 1960 (Vol. 118, No. 5).

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)

- Robert G Largess and Harvey S Horwitz (1993). "USS Triton: The Ultimate Submersible" (WARSHIP Volume XVII ed.). p. 167-187: Conway Maritime Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link)

- Norman Polmar and J.K. Moore (2004). Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines. Washington, DC: Potamac Books, Inc. ISBN: 1574885308 (paperback).

Multi-media Sources

- "Beyond Magellan" (General Dynamics, 1960) Running time - 30:00

- "USS Triton Trails Magellan" (National Geographic Society, 1960) Running tme - 40:00

- "Triton Launched: Giant Submarine First with Twin Nuclear Engines" (21 August 1958) Universal Newsreel by Ed Herlihy (1:35)

- "New Magellan: Triton Circles World Submerged" {12 May 1960) Universal Newsreel narrated by Ed Herlihy (1:11)

External links

- USS Triton (SSRN/SSN-586) @ Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships (DANFS)

- Port of Benton, Washington - Future Triton Memorial [1]

- Google satellite view of USS Triton long-term storage days at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard

- Unofficial USS Triton website

- Cold War Curiousities: U.S. Radar Picket Submarines - Article from Undersea Warfare Magazine, Winter/Spring 2002, Vol 4, No 2

- Around the World Beneath the Sea: the USS Triton Retraces Magellan's Historic Circumnavigation of the Globe

- Global Security: USS Triton (SSRN-586)

- NavSource.org: USS Triton (SSRN/SSN-586)

- Navysite.de: USS Triton (SSRN/SSN-586)

- Operation Sandblast - American Submariner Magazine

- "Nuclear Sub Coming to New Richland Park" - KNDO/KNDU - Washington, February 21, 2008 @ 12:02 PM EST, with video link (1:03)