Martin Luther

Background

Early life and education

Luther was born to Hans and Margarethe Luther (née Lindemann) on November 10, 1483 in Eisleben, Germany. He was baptized the next morning on the feast day of St. Martin of Tours. His family moved to Mansfeld in 1484, where his father operated copper mines.[9] Hans Luther was determined to see his eldest son become a lawyer. He sent Martin to schools in Mansfeld and in 1497, Magdeburg, where he attended a school operated by a lay group called the Brethren of the Common Life. In 1498, he attended school in Eisenach.[10]

At the age of seventeen in 1501, he entered the University of Erfurt, receiving his Bachelor's degree after just one year in 1502, and his Master's in 1505. In accordance with his father's wishes, he enrolled in law school at the same university, but the course of his life changed, he said, during a thunderstorm in the summer of that year. A lightning bolt struck near him as he was returning to school. Terrified, he cried out, "Help! Saint Anna, I will become a monk!"[11] He left law school, sold his books, and entered the Augustinian monastery in Erfurt on July 17, 1505.[12]

Monastic and academic life

Luther dedicated himself to monastic life, devoting himself to fasts, long hours in prayer, pilgrimage, and frequent confession. Luther tried to please God through this dedication, but it only increased his awareness of his own sinfulness.[13] He would later remark, "If anyone could have gained heaven as a monk, then I would indeed have been among them."[14] Luther described this period of his life as one of deep spiritual despair. He said, "I lost hold of Christ the Savior and Comforter and made of him a stock-master and hangman over my poor soul."[15]

Johann von Staupitz, his superior, concluded that Luther needed more work to distract him from excessive introspection and ordered him to pursue an academic career. In 1507, he was ordained to the priesthood, and in 1508 began teaching theology at the University of Wittenberg.[16] He received a Bachelor's degree in Biblical studies on March 9, 1508, and another Bachelor's degree in the Sentences by Peter Lombard in 1509.[17] On October 19, 1512, he was awarded his Doctor of Theology and, on October 21, 1512, was received into the senate of the theological faculty of the University of Wittenberg, having been called to the position of Doctor in Bible.[18] He spent the rest of his career in this position at the University of Wittenberg.

Development of his ideas

Justification by faith

From 1510 to 1520, Luther lectured on the Psalms, the books of Hebrews, Romans and Galatians. As he studied these portions of the Bible, he came to view the use of terms such as penance and righteousness by the Roman Catholic Church in new ways. He became convinced that the church had lost sight of what he saw as several of the central truths of Christianity, the most important of which, for Luther, was the doctrine of justification — God's act of declaring a sinner righteous — by faith alone. He began to teach that salvation or redemption is a gift of God's grace, attainable only through faith in Jesus as the messiah.[19]

"This one and firm rock, which we call the doctrine of justification," he wrote, "is the chief article of the whole Christian doctrine, which comprehends the understanding of all godliness."[20]

Luther came to understand justification as entirely the work of God. Against the teaching of his day that the righteous acts of believers are performed in cooperation with God, Luther wrote that Christians receive that righteousness entirely from outside themselves; that righteousness not only comes from Christ, it actually is the righteousness of Christ, imputed to us (rather than infused into us) through faith. [citation needed] "That is why faith alone makes someone just and fulfills the law," he wrote. "Faith is that which brings the Holy Spirit through the merits of Christ."[21] Faith, for Luther, is a gift from God. He explained his concept of "justification" in the Smalcald Articles:

The first and chief article is this: Jesus Christ, our God and Lord, died for our sins and was raised again for our justification (Romans 3:24-25). He alone is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world (John 1:29), and God has laid on Him the iniquity of us all (Isaiah 53:6). All have sinned and are justified freely, without their own works and merits, by His grace, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, in His blood (Romans 3:23-25). This is necessary to believe. This cannot be otherwise acquired or grasped by any work, law, or merit. Therefore, it is clear and certain that this faith alone justifies us ... Nothing of this article can be yielded or surrendered, even though heaven and earth and everything else falls (Mark 13:31).[22]

The Indulgence Controversy

The 95 Theses

On October 31, 1517, Luther wrote to Albert, Archbishop of Mainz and Magdeburg, protesting the sale of indulgences in his episcopal territories and inviting him to a disputation on the matter. In Roman Catholic theology, an "indulgence" is the remission of temporal punishment because of sins which have already been forgiven; the indulgence is granted by the church when the sinner confesses and receives absolution.

Luther enclosed in his letter to Albert a copy of his "Disputation of Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences," which came to be known known as the 95 Theses; he is also said to have posted a copy on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. In it, he challenged the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church on the nature of penance, the authority of the Pope, and the point of indulgences. He objected to a saying attributed to Johann Tetzel, a papal commissioner for indulgences that "[a]s soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs."[23] He insisted that, since pardons were God's alone to grant, those who claimed that indulgences absolved buyers from all punishments and granted them salvation were in error. Christians, he said, must not slacken in following Christ on account of such false assurances.

The 95 Theses were quickly translated from Latin into German, printed, and widely copied, making the controversy one of the first in history to be fanned by the printing press.[24] Within two weeks, the theses had spread throughout Germany; within two months throughout Europe.

Response of the papacy

In contrast to the speed with which the theses were distributed, the response of the papacy was painstakingly slow.

Cardinal Albert of Hohenzollern, Archbishop of Mainz and Magdeburg, with the consent of Pope Leo X, was using part of the indulgence income to pay his bribery debts,[10] and did not reply to Luther’s letter; instead, he had the theses checked for heresy and forwarded to Rome.[25]

Leo responded over the next three years, "with great care as is proper,"[26] by deploying a series of papal theologians and envoys against Luther. Perhaps he hoped the matter would die down of its own accord, because in 1518 he dismissed Luther as "a drunken German" who "when sober will change his mind".[27]

Widening breach

Luther's writings circulated widely, reaching France, England, and Italy as early as 1519, and students thronged to Wittenberg to hear him speak.[citation needed] He published a short commentary on Galatians and his Work on the Psalms. At the same time, he received deputations from Italy and from the Utraquists of Bohemia; Ulrich von Hutten and Franz von Sickingen offered to place Luther under their protection.[28]

This periodof Luther's career was one of the most creative and productive.[29] Three of his best known works were published in 1520: To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, Prelude on the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and Freedom of a Christian.

Excommunication and Diet of Worms

On June 15, 1520, the Pope warned Martin Luther with the papal bull Exsurge Domine that he risked excommunication unless he recanted 41 sentences drawn from his writings, including the 95 Theses, within 60 days.

That fall, Johann Eck proclaimed the bull in Meissen and other towns. Karl von Miltitz, a papal nuncio, attempted to broker a solution, but Luther, who had sent the pope a copy of On the Freedom of a Christian in October, publicly set fire to the documents from the Pope (the bull and decretals) at Wittenberg on December 10, 1520,[30] an act he defended in Why the Pope and his Recent Book are Burned and Assertions Concerning All Articles.

As a consequence, Luther was excommunicated by Leo X on January 3, 1521, in the bull Decet Romanum Pontificem.

Enforcement of the ban of the 41 sentences now fell to the secular authorities. Luther appeared, as ordered, on April 17, 1521, before the Diet of Worms (Reichstag zu Worms). This was a general assembly (a Diet) of the estates of the Holy Roman Empire that took place in Worms, a town on the Rhine. It was conducted from January 28 to May 25, 1521, with Emperor Charles V presiding over the proceedings. Prince Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, obtained an agreement that if Luther appeared he would be promised safe passage to and from the meeting.

Johann Eck, speaking on behalf of the Empire as assistant of the Archbishop of Trier, presented Luther with a table filled with copies of his writings and asked him if the books were his and if he still taught what they contained. Luther requested time to think about his answer. He prayed, consulted with friends and mediators and gave his response to the diet the next day:

Unless I shall be convinced by the testimonies of the Scriptures or by clear reason ... I neither can nor will make any retraction, since it is neither safe nor honourable to act against conscience. God help me. Amen.[31]

Over the next five days, private conferences were held to determine the Luther's fate. The Emperor presented the final draft of the Edict of Worms on May 25, 1521, declaring Luther an outlaw, banning his literature, and requiring his arrest: "We want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic".[32]

Exile at the Wartburg Castle

Luther left Worms on April 26. Frederick III arranged for him to be taken into safe custody on his way home by a company of masked horsemen, who accompanied him to Wartburg Castle at Eisenach, where he stayed for about a year. He grew a beard and wore the clothing of a knight, and assumed the pseudonym Junker Jörg (roughly equivalent to Lord or Sir George).

His time at Wartburg was another productive period. He translated the New Testament from Greek into German, aiming it at the ordinary man on the street. What Luther had to do was translate the idioms of everyday German into a written form comprehensible to people who spoke quite different dialects from each other. The forms spoken at the time are known as Middle High German and Middle Low German. He was keen to get the details right, and visited slaughterhouses to make sure he was describing Old Testament sacrifices correctly.

The translation was printed in September 1522, and sold 5,000 copies in two months. He also wrote an essay, "Concerning Confession," in which he rejected the Roman Catholic Church's requirement of confession, although he affirmed the value of private confession and absolution.

Return to Wittenberg

Around Christmas 1521 Anabaptists from Zwickau entered Wittenberg and caused considerable civil unrest. Thoroughly opposed to their radical views and fearful of their results, Luther secretly returned to Wittenberg on March 6, 1522, and the Zwickau prophets left the city. For eight days in Lent, beginning on March 9, Invocavit Sunday, and concluding the following Sunday, Luther preached eight sermons, which became known as the "Invocavit Sermons." In these sermons, Luther counseled careful reform that took into consideration the consciences of those who were not yet ready or willing to embrace reform.

Luther worked to reintroduce the practice of receiving Holy Communion in both kinds, that is, receiving both the consecrated bread and wine, rather than the practice of denying the wine to lay people. The canon of the mass was omitted. Since the former practice of penance had been abolished, communicants were now required to declare their intention to commune and to seek consolation in Christian confession and absolution. This new form of service was set forth by Luther in his Formula missæ et communionis (Form of the Mass and Communion, 1523), and in 1524 the first Wittenberg hymnal appeared with four of his own hymns, including A Mighty Fortress and the first hymn he wrote for congregational singing, Dear Christians One and All Rejoice. Because his writings were forbidden in that part of Saxon ruled by Duke George, Luther declared, in his Temporal Authority: to What Extent It Should Be Obeyed, that the civil authority could enact no laws for the soul.

Marriage and family

In April 1523, Luther arranged for Torgau burgher Leonhard Koppe to help twelve nuns escape from the Cistercian monastery in Nimbschen, near Grimma in Ducal Saxony. Koppe smuggled them out of the convent on April 4 in herring barrels. Three of the nuns went to stay with relatives, and nine were brought to Wittenberg. One of them was Katharina von Bora. All but Katharina were married shortly afterwards.

In May and June 1523, it was thought that she might marry a Wittenberg University student, Jerome Paumgartner, but his family most likely prevented it. Dr. Caspar Glatz was the next prospective husband put forward, but Katharina made it known that she wanted to marry either Luther himself or Nicholas von Amsdorf, a theologian. Initially, Luther did not feel that he was fit to be a husband considering he was excommunicated by the Pope and outlawed by the Emperor, but in May or early June 1525, it became known within his circle that he intended to marry Katharina. Forestalling any objections from friends, he acted quickly, and they married on the evening of Tuesday, June 13, 1525. They had six children, three boys and three girls, and lived in Luther's former Augustianian monastery in Wittenberg, which had been given to him as a home by the Elector.

Peasants' War

The Peasants' War (1524–1525) was in many ways a response to the preaching of Luther and others. Revolts by the peasantry had existed on a small scale since the 14th century, but many peasants mistakenly believed that Luther's attack on the Church and the hierarchy meant that the reformers would support an attack on the social hierarchy as well, because of the close ties between the secular princes and the princes of the Church that Luther condemned. Revolts that broke out in Swabia, Franconia, and Thuringia in 1524 gained support among peasants and disaffected nobles, many of whom were in debt. Gaining momentum and a new leader in Thomas Münzer, the revolts turned into an all-out war, the experience of which played an important role in the founding of the Anabaptist movement. Initially, many thought Luther supported the peasants, condemning the oppressive practices of the nobility that had incited them to revolt. As the war continued, and especially as atrocities at the hands of the peasants increased, the revolt became an embarrassment to Luther, who strongly condemned the peasants. In Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants (1525), he encouraged the nobility to crush the revolt. Many of the revolutionaries considered Luther's words a betrayal. Others withdrew once they realized that there was neither support from the Church nor from its main opponent. The war in Germany ended in 1525 when rebel forces were destroyed by the armies of the Swabian League.

Catechisms

In 1528, Luther visited parishes and schools in Saxony to determine the quality of pastoral care and Christian education. He wrote in the preface to The Small Catechism:

Mercy! Good God! what manifold misery I beheld! The common people, especially in the villages, have no knowledge whatever of Christian doctrine, and, alas! many pastors are altogether incapable and incompetent to teach.[33]

In response, he prepared the Small Catechism and Large Catechism, instructional and devotional material on the Ten Commandments, the Apostles' Creed, the Lord's Prayer, baptism, confession and absolution, and the Lord's Supper. The Small Catechism was supposed to be read by the people themselves, and the Large Catechism by the pastors; both remain popular instructional materials among Lutherans. Luther, who was modest about the publishing of his collected works, thought his catechisms were one of two works he would not be embarrassed to call his own:

Regarding [the plan] to collect my writings in volumes, I am quite cool and not at all eager about it because, roused by a Saturnian hunger, I would rather see them all devoured. For I acknowledge none of them to be really a book of mine, except perhaps the one Bondage of the Will and the Catechism.[34]

Luther's German Bible

Luther translated the Bible into German to make it more accessible to ordinary people, a task he began alone in 1521 during his stay in the Wartburg castle, publishing The New Testament in September 1522 and, in collaboration with Johannes Bugenhagen, Justus Jonas, Caspar Creuziger, Philipp Melanchthon, Matthäus Aurogallus, and George Rörer, the Old and New Testaments together in 1534. He worked on refining the translation for the rest of his life.

The Luther Bible contributed to the emergence of the modern German language and is regarded as a landmark in German literature. The 1534 edition was influential on William Tyndale's translation,[35] a precursor of the King James Bible.[36] Philip Schaff, the 19th century theologian, said of the work:

The richest fruit of Luther's leisure in the Wartburg, and the most important and useful work of his whole life, is the translation of the New Testament, by which he brought the teaching and example of Christ and the Apostles to the mind and heart of the Germans in life-like reproduction. It was a republication of the gospel. He made the Bible the people's book in church, school, and house.[37]

Liturgy and church government

Luther’s German Mass of 1526 provided for weekday services and for catechetical instruction. He strongly objected, however, to making a new law of the forms and urged the retention of other good liturgies. While Luther advocated Christian liberty in liturgical matters in this way, he also spoke out in favor of maintaining and establishing liturgical uniformity among those sharing the same faith in a given area. In other words, freedom was to be tempered by loving concern for the fellow Christian lest he be offended or confused. He saw in liturgical uniformity a fitting outward expression of unity in the faith, while in liturgical variation, an indication of possible doctrinal variation. He did not consider liturgical change a virtue, especially when it might be made by individual Christians or congregations: he was content to conserve and reform what the Church had inherited from the past. Therefore Luther, while eliminating and condemning those parts of the mass that taught that the Eucharist was a propitiatory sacrifice and the Body and Blood of Christ by transubstantiation,[38] retained the use of historic liturgical forms and customs.

Eucharist controversy

Luther's views on the Eucharist, the sacrament of the Lord's Supper, were put to the test in October 1529 at the Marburg Colloquy, an assembly of Protestant theologians gathered by Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, to establish doctrinal unity in the emerging Protestant states. Agreement was achieved on most points, the exception being the nature of the Eucharist, an issue crucial to Luther.[39]

The theologians, including Zwingli, Karlstadt, Jud, and Œcolampadius, differed among themselves on the significance of the words of institution spoken by Jesus at the Last Supper: "This is my body which is for you", "This cup is the new covenant in my blood" (1 Corinthians 11:23–26). Luther insisted on the Real Presence of the body and blood of Christ in the consecrated bread and wine, but the other theologians believed God to be only symbolically present: Zwingli, for example, denied Jesus's ability to be in more than one place at a time. But Luther, who affirmed the doctrine of Hypostatic Union, that Jesus is one and the same as God, was clear:

For I do not want to deny in any way that God’s power is able to make a body be simultaneously in many places, even in a corporeal and circumscribed manner. For who wants to try to prove that God is unable to do that? Who has seen the limits of his power?[40]

Despite these disagreements on the Eucharist, the Marburg Colloquy paved the way for the signing in 1530 of the Augsburg Confession and for the formation of the Schmalkaldic League the following year by leading Protestant nobles such as Philip of Hesse, John Frederick of Saxony, and George, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach. According to Luther, agreement in the faith was not necessary prior to entering political alliances. Nevertheless, interpretations of the Eucharist differ among Protestants to this day.

Augsburg confession

Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, convened an Imperial Diet in Augsburg in 1530 with the goal of uniting the empire against the Ottoman Turks, who had besieged Vienna the previous autumn.

To achieve unity, Charles required a resolution of the religious controversies in his realm. Luther, still under the Imperial Ban, was left behind at the Coburg fortress while his elector and colleagues from Wittenberg attended the diet. The Augsburg Confession, a summary of the Lutheran faith authored by Philipp Melanchthon but influenced by Luther,[39] was read aloud to the emperor. It was the first specifically Lutheran confession included in the Book of Concord of 1580, and is regarded as the principal confession of the Lutheran Church.

Philip of Hesse controversy

In 1539, Luther became involved in controversy surrounding the bigamy of Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, who wanted to marry one of his wife's ladies-in-waiting. Luther ruled that polygamy was acceptable, noting that the patriarchs of the Old Testament had had more than one wife, and so Philip entered into the second marriage in secret. Philip's sister made news of the marriage public a few weeks later, scandalizing Germany.[2]

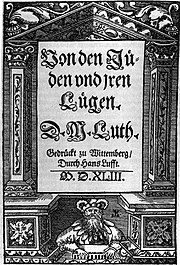

Luther and antisemitism

American historian Robert Michael writes that Luther was concerned with the Jewish question all his life.[41] Luther's theology centered on the idea of salvation through the acceptance of Jesus as the messiah. In rejecting that view of Jesus, the Jews became the "quintessential other,"[42] a model of the opposition to the Christian view of God. In his earlier work, Luther advocated kindness toward the Jews, with the aim of converting them to Christianity. When his efforts at conversion failed, he became increasingly bitter toward them.[43] His main works on the Jews were his 60,000-word treatise On the Jews and Their Lies, and Vom Schem Hamphoras, both written in 1543, three years before his death. He argued that the Jews were no longer the chosen people, but were "the devil's people." They were "base, whoring people, that is, no people of God, and their boast of lineage, circumcision, and law must be accounted as filth."[44] He advocated setting synagogues on fire, destroying Jewish prayerbooks, forbidding rabbis from preaching, seizing Jews' property and money, smashing up their homes, and ensuring that these "poisonous envenomed worms" be forced into labor or expelled "for all time."[45] He also seemed to sanction their murder,[46] writing "We are at fault in not slaying them."[47]

Luther successfully campaigned against the Jews in Saxony, Brandenburg, and Silesia. Michael writes that the city of Strasbourg was asked by Josel of Rosheim to forbid the sale of Luther's anti-Jewish works; they refused initially, but relented when a Lutheran pastor in Hochfelden argued in a sermon that his parishioners should murder Jews. Luther's influence persisted after his death. Throughout the 1580s, riots saw the expulsion of Jews from several German Lutheran states.[48]

At the heart of the debate about Luther's writings on Jews is the degree to which they influenced German antisemitism in general, and Nazi ideology in particular. The prevailing view[49] among historians is that his anti-Jewish rhetoric contributed significantly to the development of antisemitism in Germany,[50] and in the 1930s and 1940s provided an ideal foundation for the National Socialist's attacks on Jews.[51] According to Michael, Luther's work acquired the status of scripture within Germany, and he became the most widely read author of his generation, in part because of the coarse and passionate nature of the writing. Reinhold Lewin writes that "whoever wrote against the Jews for whatever reason believed he had the right to justify himself by triumphantly referring to Luther." According to Michael, just about every anti-Jewish book printed in the Third Reich contained references to and quotations from Luther. Heinrich Himmler wrote admiringly of his writings and sermons on the Jews in 1940.[52] The city of Nuremberg presented a first edition of On the Jews and their Lies to Julius Streicher, editor of the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer, on his birthday in 1937; the newspaper described it as the most radically anti-Semitic tract ever published.[53] It was publicly exhibited in a glass case at the Nuremberg rallies and quoted in a 54-page explanation of the Aryan Law by Dr. E.H. Schulz and Dr. R. Frercks.[43] On December 17, 1941, seven Lutheran regional church confederations issued a statement agreeing with the policy of forcing Jews to wear the yellow badge, "since after his bitter experience Luther had already suggested preventive measures against the Jews and their expulsion from German territory."

A minority see Luther's influence as limited, and Nazi use of his work as opportunistic. Martin Brecht argues that there is a world of difference between Luther's belief in salvation, which depended on a faith in Jesus as the messiah — a belief Luther criticized the Jews for rejecting — and the Nazi's ideology of racial antisemitism.[54] Johannes Wallmann writes that Luther's writings against the Jews were largely ignored in the 18th and 19th centuries;[55] Uwe Siemon-Netto argues that it was because the Nazis were already anti-Semites that they revived Luther's work.[56][57] Hans J. Hillerbrand agrees that to focus on Luther is to adopt an essentially ahistorical perspective of Nazi antisemitism that ignores other contributory factors in German history.[58][59]

Other scholars argue that, even if his views were merely anti-Judaic, the violence of them lent a new element to the standard Christian suspicion of Judaism. Ronald Berger writes that Luther is credited with "Germanizing the Christian critique of Judaism and establishing anti-Semitism as a key element of German culture and national identity."[60] Paul Rose argues that he caused a "hysterical and demonizing mentality" about Jews to enter German thought and discourse, a mentality that might otherwise have been absent.[61]

Luther, the Pope, and the Council of Trent

Luther was known for his bitter attacks on the Pope, which grew more vitriolic in his later years. In the context of the opening of the Council of Trent in 1545, he wrote a pamphlet entitled, Against the Roman Papacy an Institution of the Devil.[62] One commentator observed:

Perhaps no one in history abhorred the Church and all she stands for more than Martin Luther. His diatribes against the papacy and the structure of the Church in general are well known. Popes, bishops, and cardinals are referred to as "Roman sodom." One of Luther's pamphlets is entitled "Against the Papacy Established by the Devil" (1545). He once blessed a group of followers, saying: "May the Lord fill you with His blessings and with hatred of the Pope. [63]

Luther on witchcraft

Luther shared some of the superstitions about witchcraft that were common in his time.[64] He believed that it was inimical to Christianity. In his Small Catechism, he taught that it was a sin against the second commandment,[65] and that, with the help of the devil, witches were able to steal milk simply by thinking of a cow.[66] He is reported to have said in a "table talk" that he would burn them himself:

On 25 August 1538 there was much discussion about witches and sorceresses who steal chicken eggs out of nests, or steal milk and butter. Doctor Martin said: "One should show no mercy to these [women]; I would burn them myself, for we read in the Law that the priests were the ones to begin the stoning of criminals."[67]

Final years and death

Luther had been suffering from ill health for years, including constipation, hemorrhoids, dizziness, fainting spells, and roaring in the ears. From 1531–1546, his health deteriorated further. The years of struggle with Rome, the antagonisms with and among his fellow reformers, and the scandal which ensued from the bigamy of the Philip of Hesse incident, in which Luther had played a leading role, all may have contributed. In 1536, he began to suffer from kidney and bladder stones, and arthritis, and an ear infection ruptured an ear drum. In December 1544, he began to feel the effects of angina.[68]

His physical health made him short-tempered and even harsher in his writings and comments. His wife Katie was overheard saying, "Dear husband, you are too rude," and he responded, "They teach me to be rude."[69]

His last sermon was delivered at Eisleben, his place of birth, on February 15, 1546, three days before his death.[70] It was "entirely devoted to the obdurate Jews, whom it was a matter of great urgency to expel from all German territory," according to Léon Poliakov.[71] James Mackinnon writes that it concluded with a "fiery summons to drive [the Jews] bag and baggage from their midst, unless they desisted from their calumny and their usury and became Christians."[72] Luther said, "we want to practise Christian love toward them and pray that they convert," but also that they are "our public enemies ... and if they could kill us all, they would gladly do so. And so often they do."[73]

Luther's final journey, to Mansfeld, was taken due to his concern for his siblings' families continuing in their father Hans Luther's copper mining trade. Their livelihood was threatened by Count Albrecht of Mansfeld bringing the industry under his own control. The controversy that ensued involved all four Mansfeld counts: Albrecht, Philip, John George, and Gerhard. Luther journeyed to Mansfeld twice in late 1545 to participate in the negotiations for a settlement, and a third visit was needed in early 1546 for their completion.

The negotiations were successfully concluded on February 17, 1546. After 8:00 p.m., he experienced chest pains. When he went to his bed, he prayed, "Into your hand I commit my spirit; you have redeemed me, O Lord, faithful God" (Ps. 31:5), the common prayer of the dying. At 1:00 a.m. he awoke with more chest pain and was warmed with hot towels. He thanked God for revealing his son to him in whom he had believed. His companions, Justus Jonas and Michael Coelius, shouted loudly, "Reverend father, are you ready to die trusting in your Lord Jesus Christ and to confess the doctrine which you have taught in his name?" A distinct "Yes" was Luther's reply. (It was believed at the time that sudden cardiac arrest or stroke was a sign that Satan had taken a man's soul; Luther's companions stressed that he had gradually weakened and commended himself into God's hands.[74])

An apoplectic stroke deprived him of his speech, and he died shortly afterwards at 2:45 a.m., February 18, 1546, aged 62, in Eisleben, the city of his birth. He was buried in the Castle Church in Wittenberg, beneath the pulpit.[75]

A piece of paper was later found on which he had written his last statement. The statement was in Latin, apart from "We are beggars," which was in German.

1. No one can understand Vergil's Bucolics unless he has been a shepherd for five years. No one can understand Vergil's Georgics,

unless he has been a farmer for five years.

2. No one can understand Cicero's Letters (or so I teach), unless he has busied himself in the affairs of some prominent state for twenty years.

3. Know that no one can have indulged in the Holy Writers sufficiently, unless he has governed churches for a hundred years with the prophets, such as Elijah and Elisha, John the Baptist, Christ and the apostles.

Do not assail this divine Aeneid; nay, rather prostrate revere the ground that it treads.

Recent trends in research

In recent years, there has been significant translation and discovery of some of Luther's most controversial works. These publications have augmented the large body of Luther’s work that was translated and published by various Lutheran Church organizations and their related publishing companies. The new publications present a more controversial picture of this very prolific writer and his complex personality.

An English translation of On the Jews and Their Lies was published commercially in 1971, and revealed to many readers a side of Luther they had not previously known. Another of Luther's works was Vom Schem Hamphoras, which contains graphic "toilet talk" against the Jews; this was translated and published independently as part of The Jew In Christian Theology by Gerhard Falk in 1971.

There is no known English translation of Against the Papacy at Rome Founded by the Devil (1545), but it has been described as "one of Luther's most coarse and vehement works." It is said to contain scatological satires of the Pope, along with illustrations by Cranach, who is known for painting Luther’s portrait.[78]

Against Hanswurst (1541) was translated as part of Luther's Works and is described as "rivaling his anti-Jewish treatises for vulgarity and violence of expression."[79]

Since some of these works are only now being revealed, and the only English descriptions are often secondary sources, researchers disagree as to their relevance. However, the trend has been toward translation, publication and review, rather than silent archiving.

See also

- "A Mighty Fortress is Our God"

- Christianity

- Christianity and anti-Semitism

- Jesus

- Real Presence

- Consubstantiation

- Erasmus' Correspondents

- Huldrych Zwingli

- John Calvin

- Luther's Seal

- Lutheranism

- Protestant Reformation

Notes

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1914). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1914). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

- ^ Plass, Ewald M. "Monasticism," in What Luther Says: An Anthology. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1959, 2:964.

- ^ a b Hillerbrand, Hans J. "Martin Luther," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2007.

- ^ Fahlbusch, Erwin and Bromiley, Geoffrey William. The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Grand Rapids, MI: Leiden, Netherlands: Wm. B. Eerdmans; Brill, 1999–2003, 1:244.

- ^ Tyndale's New Testament, trans. from the Greek by William Tyndale in 1534 in a modern-spelling edition and with an introduction by David Daniell. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989, ix–x.

- ^ Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther. New York: Penguin, 1995, 269.

- ^ Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther. New York: Penguin, 1995, 223.

- ^ Luther, Martin. "On the Jews and Their Lies," tr. Martin H. Bertram, in Sherman, Franklin. (ed.) Luther's Works. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971, 47:268–72, hereafter cited as LW.

- ^ McKim, Donald K. (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Martin Luther. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003, 58; Berenbaum, Michael. "Anti-Semitism," Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed January 2, 2007.

- ^ Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:3–5.

- ^ a b Rupp, Ernst Gordon. "Martin Luther," Encyclopædia Britannica, accessed 2006.

- ^ Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:48.

- ^ Schwiebert, E.G. Luther and His Times. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1950, 136.

- ^ Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther. New York: Penguin, 1995, 40-42.

- ^ Kittelson, James. Luther The Reformer. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishing House, 1986), 53.

- ^ Kittelson, James. Luther The Reformer. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishing House, 1986, 79.

- ^ Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther. New York: Penguin, 1995, 44-45.

- ^ Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:93.

- ^ Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:12-27.

- ^ Wriedt, Markus. "Luther's Theology," in The Cambridge Companion to Luther. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003, 88–94.

- ^ Bouman, Herbert J. A. "The Doctrine of Justification in the Lutheran Confessions", Concordia Theological Monthly, November 26, 1955, No. 11:801.

- ^ Luther's Definition of Faith

- ^ Luther, Martin. "The Smalcald Articles," in Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions. (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2005, 289, Part two, Article 1.

- ^ Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther. New York: Penguin, 1995, 60; Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:182; Kittelson, James. Luther The Reformer. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishing House, 1986),104.

- ^ Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:204-205.

- ^ Treu, Martin. Martin Luther in Wittenberg: A Biographical Tour. Wittenberg: Saxon-Anhalt Luther Memorial Foundation, 2003, 31.

- ^ Papal Bull Exsurge Domine.

- ^ Schaff, Philip. History of the Christian Church. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1910, 7:99; Polack, W.G. The Story of Luther. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1931, 45.

- ^ Macauley Jackson, Samuel and Gilmore, George William. (eds.) "Martin Luther", The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, New York, London, Funk and Wagnalls Co., 1908–1914; Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1951), 71.

- ^ Spitz, Lewis W. The Renaissance and Reformation Movements, St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1987, 338.

- ^ Brecht, Martin. (tr. Wolfgang Katenz) "Luther, Martin," in Hillerbrand, Hans J. (ed.) Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, 2:463.

- ^ Macauley Jackson, Samuel and Gilmore, George William. (eds.) "Martin Luther", The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, New York, London, Funk and Wagnalls Co., 1908–1914; Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1951), 72.

- ^ "Edict of Worms", translated by De Lamar Jensen and Jacquelin Delbrouwire.

- ^ Luther, Martin. "Preface", Small Catechism.

- ^ Luther, Martin. Luther's Works. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971, 50:172-173. The remark indicates that he saw himself as the mythological Saturn, who devoured his children; Luther wanted to get rid of many of his writings except for the two mentioned. The Large and Small Catechisms are spoken of as one work by Luther in this letter.

- ^ Tyndale's New Testament, xv, xxvii.

- ^ Tyndale's New Testamemt, ix–x.

- ^ Schaff, Philip. History of the Christian Church, 8 vols., New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1910.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, “Luther, Martin,” 73.

- ^ a b Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin", 74.

- ^ LW 37:223–224.

- ^ Stöhr, Martin. "Die Juden und Martin Luther," in Kremers, Heinz et al (eds.) Martin Luther und die Juden; die Juden und Martin Luther. Neukirchener publishing house, Neukirchen Vluyn 1985, 1987 (2. Edition).p. 90. Taken from Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. See also Oberman, Heiko. Luther: Between Man and Devil. New Haven, 1989.

- ^ Hsia, R. Po-chia. "Jews as Magicians in Reformation Germany," in Gilman, Sander L. and Katz, Steven T. Anti-Semitism in Times of Crisis, New York: New York University Press, 1991, 119-120, cited in Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- ^ a b Noble, Graham. "Martin Luther and German anti-Semitism," History Review (2002) No. 42:1-2.

- ^ Luther, Martin. On the Jews and their Lies, 154, 167, 229, cited in Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- ^ Luther, Martin. "On the Jews and Their Lies," Luther's Works 47:268-271.

- ^ Michael, Robert. "Luther, Luther Scholars, and the Jews," Encounter, 46 (Autumn 1985) No.4:343.

- ^ Luther, Martin. On the Jews and Their Lies, cited in Michael, Robert. "Luther, Luther Scholars, and the Jews," Encounter 46 (Autumn 1985) No. 4:343-344.

- ^ Vincent Fettmilch, a Calvinist, reprinted On the Jews and their Lies in 1612 to stir up hatred against the Jews of Frankfurt. Two years later, riots in Frankfurt saw the deaths of 3,000 Jews and the expulsion of the rest. Fettmilch was executed by the Lutheran city authorities, but Robert Michael writes that his execution was for attempting to overthrow the authorities, not for his offenses against the Jews.

- ^ Wallmann, Joannes. "The Reception of Luther's Writings on the Jews from the Reformation to the End of the 19th Century", Lutheran Quarterly, n.s. 1 (Spring 1987) 1:72-97: "The assertion that Luther's expressions of anti-Jewish sentiment have been of major and persistent influence in the centuries after the Reformation, and that there exists a continuity between Protestant anti-Judaism and modern racially oriented anti-Semitism, is at present wide-spread in the literature; since the Second World War it has understandably become the prevailing opinion."

- ^ For similar views, see:

- Berger, Ronald. Fathoming the Holocaust: A Social Problems Approach (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 2002), 28.

- Rose, Paul Lawrence. "Revolutionary Antisemitism in Germany from Kant to Wagner," (Princeton University Press, 1990), quoted in Berger, 28);

- Shirer, William. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1960).

- Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1987), 242.

- Poliakov, Leon. History of Anti-Semitism: From the Time of Christ to the Court Jews. (N.P.: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 216.

- Berenbaum, Michael. The World Must Know. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 1993, 2000), 8–9.

- ^ Grunberger, Richard. The 12-Year Reich: A Social History of Nazi German 1933-1945 (NP:Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971), 465.

- ^ Himmler wrote: "what Luther said and wrote about the Jews. No judgment could be sharper."

- ^ Ellis, Marc H. Hitler and the Holocaust, Christian Anti-Semitism", (NP: Baylor University Center for American and Jewish Studies, Spring 2004), Slide 14. [1]

- ^ Brecht 3:351.

- ^ Johannes Wallmann, "The Reception of Luther's Writings on the Jews from the Reformation to the End of the 19th Century", Lutheran Quarterly, n.s. 1 (Spring 1987) 1:72-97.

- ^ Siemon-Netto, The Fabricated Luther, 17-20.

- ^ Siemon-Netto, "Luther and the Jews," Lutheran Witness 123 (2004) No. 4:19, 21.

- ^ Hillerbrand, Hans J. "Martin Luther," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2007. Hillerbrand writes: "[H]is strident pronouncements against the Jews, especially toward the end of his life, have raised the question of whether Luther significantly encouraged the development of German anti-Semitism. Although many scholars have taken this view, this perspective puts far too much emphasis on Luther and not enough on the larger peculiarities of German history."

- ^ For similar views, see:

- Bainton, Roland, 297;

- Briese, Russell. "Martin Luther and the Jews," Lutheran Forum (Summer 2000):32;

- Brecht, Martin Luther, 3:351; Mark U. Edwards, Jr. Luther's Last Battles: Politics and Polemics 1531-46. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983), 139;

- Gritsch, Eric. "Was Luther Anti-Semitic?", Christian History, No. 3:39, 12.; *James M. Kittelson, Kittelson, James M., Luther the Reformer, 274;

- Richard. Martin Luther, 377;

- Oberman, Heiko. The Roots of Anti-Semitism: In the Age of Renaissance and Reformation (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984), 102;

- Rupp, Gordon. Martin Luther, 75;

- Siemon-Netto, Uwe. Lutheran Witness, 19.

- ^ Berger, 28.

- ^ Rose as quoted in Berger, 28.

- ^ LW 41:259-376.

- ^ Emanuel Valenza, "Christ Among Us? No. Heresy and Revolution, Yes!" The Angellus March 1985, Volume VIII, Number 3, citing The Catholic Encyclopedia 1913 ed. s.v. "Luther." Vol. 9.

- ^ Susan C. Karant-Nunn and Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks, Luther on Women: A Sourcebook, (Cambridge: Cambridge U. Press, 2003), 228.

- ^ Martin Luther, Luther's Little Instruction Book, Trans. Robert E. Smith, (Fort Wayne: Project Wittenberg, 2004), Small Catechism 1.2.

- ^ Sermon on Exodus, 1526, WA 16, 551 f.

- ^ WA Tr 4, 51-52, no. 3979 quoted and translated in Karant-Nunn, 236. The original Latin and German text is: "25, Augusti multa dicebant de veneficis et incantatricibus, quae ova ex gallinis et lac et butyrum furarentur. Respondit Lutherus: Cum illis nulla habenda est misericordia. Ich wolte sie selber verprennen, more legis, ubi sacerdotes reos lapidare incipiebant. Cf. also WA 1, 403 & 407; LW 26, 190; LW 30, 91; LW 2, 11; WA Tr 2, 504-05, no. 2529b; WA Tr 3, 131-32, no. 2982b; WA Tr 3, 445-46, no. 3601; WA Tr 4, 10-11, no. 3921; WA Tr 4, 43-44, no. 3969; WA Tr 4, 416, no. 4646; WA Tr 4, 222, no. 6836. All are quoted and translated in Karant-Nunn, 230-237.

- ^ Edwards, 9.

- ^ Spitz, 354.

- ^ Luther, Martin. Sermon No. 8, "Predigt über Mat. 11:25, Eisleben gehalten," February 15, 1546, Luthers Werke, Weimar 1914, 51:196-197.

- ^ Poliakov, Léon. From the Time of Christ to the Court Jews, Vanguard Press, p. 220.

- ^ Mackinnon, James. Luther and the Reformation. Vol. IV, (New York: Russell & Russell, 1962, p. 204.

- ^ Luther, Martin. Admonition against the Jews, added to his final sermon, cited in Oberman, Heiko. Luther: Man Between God and the Devil, New York: Image Books, 1989, p. 294.

- ^ Oberman, Heiko, Luther: Man Between God and the Devil. New York; Doubleday, 1990, 3-4

- ^ cf. Brecht, 3:369–379.

- ^ Kellermann, James A. (translator) "The Last Written Words of Luther: Holy Ponderings of the Reverend Father Doctor Martin Luther". February 16, 1546.

- ^ Original German and Latin of Luther's last written words is: "Wir sein pettler. Hoc est verum." Heinrich Bornkamm, Luther's World of Thought, tr. Martin H. Bertram (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1958), 291.

- ^ "Martin Luther", Onlineliterature.com, accessed May 2007.

- ^ Edwards, Mar U. "Luther's Last Battles", Concordia Theological Quarterly, Vol. 48, Nos. 2 & 3, April-July 1984.

Further reading

- For the works of Luther himself, see List of books by Martin Luther

- Original writings of Luther and contemporaries

- Project Wittenberg, an archive of Lutheran documents

- Full text of the 95 Theses

- Full text of the Smalcald Articles

- Full text of the Small Catechism

- Full text of the Large Catechism

- Excerpts from Against the Murderous, Thieving Peasants

- Prelude On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church

- Commentary on The Magnificat (Luke 1:46-55), 1521 [2] [3]

- Online information on Luther and his work

- The Musical Reforms of Martin Luther

- KDG Wittenberg's Luther site (7 languages)

- Martin Luther – ReligionFacts.com

- Memorial Foundation of Saxony Anhalt (German/English)

- Martin Luther – PBS movie

- Luther – theatrical release

- Martin Luther: The Reformer Travelling Exhibition

- New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge article on "Luther, Martin"

- Martin Luther - Eine Bibliographie (German)

- Works by Martin Luther at Project Gutenberg

- Martin Luther

- The "seat" of the Reformation - (BBC News)

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Martin Luther

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Martin Luther

- Luther, Martin in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Martin Luther and the German Reformation

- The Weblog about Luther's hometown Wittenberg (in English)

- Luther's Men - Discuss Theology and Beer

- Luther On Islam

- 1483 births

- 1546 deaths

- Martin Luther

- Antisemitism

- Anti-Catholicism

- Augustinians

- Bible translators

- Charismatic religious leaders

- Christian religious leaders

- Lutheran writers

- Lutheran hymnwriters

- People related to Catholic-related controversies

- Founders of religions

- German Lutherans

- German Christian ministers

- German theologians

- Late Middle Ages

- Lutheran saints

- Natives of Saxony-Anhalt

- People excommunicated by the Roman Catholic Church

- Protestant Reformers

- Renewers of the church

- Sermon writers

- Walhalla enshrinees