Referendums in East and West Prussia

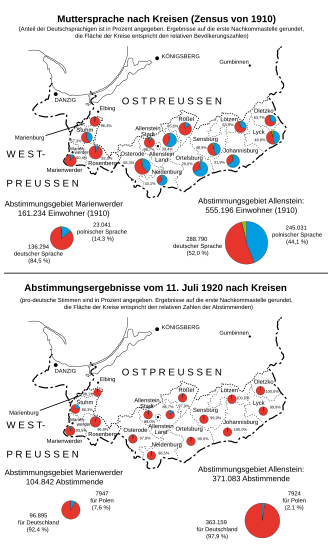

As part of the referendums in the wake of the Versailles Treaty , referendums were also held in parts of East and West Prussia on July 11, 1920 . In East Prussia, votes were mainly taken in the Olsztyn administrative district (with small changes) and in West Prussia in several districts of the former Marienwerder administrative district east of the Vistula . Those entitled to vote could decide on the future state affiliation of the areas. In the Allenstein voting area, over 97% and in the Marienwerder voting area, over 92% of the voters voted to remain with East Prussia and thus with the German Reich and against cession to the Second Polish Republic . These results were also remarkable in that a significant part of the population in the voting areas was Polish as their mother tongue.

prehistory

After the end of the First World War and the state restoration of Poland, the demarcation between Poland and the German Empire was controversial. While the Treaty of Versailles granted most of the Prussian province of Posen (historical Greater Poland ) and the Polish Corridor to the Polish state without a referendum, in the southern districts of East Prussia, the parts of West Prussia east of the Vistula , and in Upper Silesia , referendums were held on the further state Affiliation to be decided ( referendums in the wake of the Versailles Treaty ). Two voting areas ( English plebiscite areas ; French zones du plébiscite ) were planned at the borders of East Prussia : the Marienwerder voting area in West Prussia along the Vistula and in East Prussia the Allenstein voting area, the Allenstein administrative district and the Oletzko district ( Masuria ). The Polish delegation in Versailles originally demanded the cession of these disputed areas to Poland without any referendum. In addition, northern East Prussia was to fall to Lithuania, and the remaining part around Königsberg was to become a League of Nations mandate that was independent of Germany and that, according to Polish politicians, should also become part of Poland in the long term. The Friedrich Ebert government protested against this and, above all, at the urging of British Prime Minister David Lloyd George , votes were organized under Allied supervision.

According to the regulations in Articles 94–98 of the Versailles Treaty, the voting area was demilitarized and subordinated to a voting commission subordinate to the League of Nations . After the withdrawal of the German military in the first week of February, she took over the administration of the voting area on February 17, 1920 and stationed British and Italian troops to monitor the voting. German administrative authorities remained in office, they were forbidden from any contact with superior departments in Berlin or Königsberg, and the officials working there had to take an oath of loyalty to the commission.

Germany and Poland then developed intensive campaigns to advertise their respective national affiliations. Various organizations with a total of around 220,000 members were united under the umbrella of the East German Homeland Service in order to promote Germany's continued presence. Paul Hensel and Max Worgitzki were among the leading figures . The Polish side founded the “Masurian Voting Committee” in Warsaw in November 1919, chaired by Juliusz Bursche , who later became the bishop of the Evangelical-Augsburg Church in Poland . However, there was a lack of suitable agitators on this side, which is why Poles who immigrated from other areas of the Prussian monarchy, for the most part, campaigned for a connection to Poland. These were supported by volunteers from Poland who, on the one hand, rarely had a good knowledge of the Masurian population and, on the other hand, were Catholics, which was not necessarily useful for communication with the Protestant Masurians.

All residents of the voting area who were older than 20 years and those born there before January 1, 1905 were entitled to vote. As a result, numerous Masurians who had emigrated to the Ruhr area in the course of industrialization took part in the vote. This regulation was based on a proposal by Ignacy Jan Paderewski . Likewise, the determination of the voting alternatives East Prussia / Poland (not Germany / Poland ) should go back to a request by the Polish delegation in Versailles, headed by Roman Dmowski , who hoped that the participation of the Ruhr Poles , regarded as a Polish minority, would improve their chances.

Framework conditions for the referendum on July 11, 1920

According to the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was supposed to pay substantial reparations, the amount of which the Reparations Commission only set after the conclusion of the treaty and which had to be paid from May 1, 1921. In contrast to its neighbors, Germany was on the one hand so burdened with high foreign debts, on the other hand - except in East Prussia - it was hardly damaged by the war. Germany's energy reserves were controlled by the Allies and industry was on the ground. The political situation of the German state was uncertain due to political unrest such as the Kapp Putsch . An improvement in the economic situation for the Masurians in the German Reich was not to be expected, which is why the German side could only point out the Polish difficulties that existed in the election campaign. However, despite its difficulties in repairing the war damage in East Prussia, the German Reich had granted generous loans.

Poland was on the defensive in the Polish-Soviet war , the Red Army had been besieging Lviv since June 1920 , and the prospect of becoming part of a state that was currently at war was not very attractive. The material prospects were uncertain in spite of Polish propaganda to the contrary. In East Prussia in particular, the German Reich granted generous loans to repair the damage caused by the war. According to Prussian statistics, the Polish-speaking proportion of the population in Masuria had decreased from over 75% to the last (1910) around 44% since the establishment of the empire in 1871. In reality, however, the percentage of Polish speakers was probably higher because many actually primarily Polish-speaking Masurians did not want to refer to themselves as Poles, since everything Polish or Polish-Masurian had little regard for German culture (“Where culture ends, there is begins the Masur ”). The Russian invasion of the country and the great victories of the German armies at Tannenberg (1914) and at the Masurian Lakes (1915), which seemed to show the superiority of the German over the eastern “Slavic” culture, left a lasting impression on the people of Masuria . The reconstruction of the country, which had been badly damaged by the war, had already started again during the war with the relatively generous help of the Prussian government and many German cities had taken on war sponsorships for East Prussian circles in order to support them materially.

The Polish side, on the other hand, misjudged the mood of the Masurian population from the start. The main aim of Polish propaganda was to portray the Masurians as Poles who had been oppressed by the Prussians and Germans for centuries and who would gain their freedom by joining the newly formed Poland. However, this propaganda did not meet with any response from the Masurian population, the overwhelming majority of whom saw themselves as state-loyal, conservative Prussians. On the contrary, the aggressively nationalist statements made by Polish politicians were perceived as a threat. Accordingly, the Polish side also lacked supporters for organizing an “election campaign” in the voting areas, as there had never been a major pro-Polish movement there before. The German preparations, however, were supported by the fact that, unlike in other voting areas, the German administration was not suspended for the period before and during the vote.

Those entitled to vote returning from outside the voting area were given free transport and accommodation, and any loss of earnings was compensated for. Since the Polish authorities refused to allow around 25,000 voters to pass through the Polish Corridor , the East Prussian Sea Service was created. Air transport was organized from Stolp Airport.

Interallied Commission

On February 14th and 17th, 1920 the Inter-Allied Commission took over the supervision in Allenstein and Marienwerder. The district president in Allenstein Matthias von Oppen and the mayor of the city Georg Zülch were expelled. In their place, Wilhelm von Gayl represented German interests as Reich and State Commissioner. As he himself wrote, however, “a double task was set for him: He had to protect German interests vis-à-vis the Commission and the Poles, but also to help the Commission with information and advice, and to mediate its dealings with the German government agencies outside the area. He was not a unilateral lobbyist like the Polish Consul General, but was organically linked to the Commission through a corresponding agreement. "

In the service of the commission for the East Prussian voting area were 88 senior civil servants and officers: 34 British, 24 French, 23 Italians and 7 Japanese. Great Britain's envoy Sir Ernest Amelius Rennie (1868–1935) was in the chair . The German agent for the West Prussian voting area was initially the former district administrator of Graudenz, privy councilor Hans Kutter (1870-1929). After the Kapp Putsch , he was replaced by Theodor von Baudissin (1874–1950), district administrator in Neustadt / West Prussia. The Polish side was in Marienwerder through Stanislaus Graf von Sierakowski ( Polish Stanisław Sierakowski , 1891-1939), in Allenstein through the later Polish Consul General Zenon Eugeniusz Lewandowski (1859-1929), followed by Prince Henryk Korybut-Woroniecki (1891-1941), represented (Weichbrodt 1980).

For the voting area in the province of West Prussia, the Inter-Allied Commission consisted of the Italian State Commissioner Angelo Pavia as chairman, the English diplomat Henry Beaumont , the French diplomat René de Cherisey and the Japanese diplomat Morikazu Ida .

Voting results

The results were published by the statistical office of the Republic of Poland in the Statistical Yearbook 1920/22, by the Prussian State Statistical Office and summarized in an appendix to the German census of 1925 by the Reich Statistical Office .

Allenstein voting area

Of the 422,067 eligible voters, 87.31% took part. 363,209 (97.86%) voted to remain in East Prussia / Germany and 7,924 (2.11%) to join Poland. The communities of Klein Lobenstein, Klein Nappern and Groschken in the Osterode district, which are located directly on the border, voted in favor of joining Poland and were ceded to Poland. Another 25 communities, the majority of which voted for Poland, remained with East Prussia, as otherwise they would have formed exclaves.

The area around Soldau , part of the Neidenburg district, had to be ceded to Poland without a referendum. The reason for this was the Prussian Eastern Railway Line Danzig – Warsaw running through Soldau . The following table shows the results of the voting.

| circle | Area (km²) |

Population 1910 |

Languages 1910 (number of speakers) | Population (Oct 8, 1919) |

voting justified |

Valid votes | Votes in percent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polish | German | other language |

German and another |

All in all | for Poland |

for Germany |

for Poland |

for Germany |

|||||

| Elk ( Ełk ) | 1,114.0 | 55,579 | 25,755 | 27,138 | 67 | 2,619 | 57,414 | 40,440 | 36,573 | 44 | 36,529 | 0.12 | 99.88 |

| Johannisburg ( Jańsbork ) | 1,682.4 | 51,399 | 33,344 | 16,379 | 35 | 1,641 | 52,403 | 38,964 | 33,831 | 14th | 33,817 | 0.04 | 99.96 |

| Soldering ( Lec ) | 894.5 | 41.209 | 13.007 | 26,352 | 43 | 1,807 | 45,681 | 33,339 | 29,359 | 10 | 29,349 | 0.03 | 99.97 |

| Neidenburg ( Nibork ) | 1,071.2 | 32,610 | 20,075 | 10,779 | 42 | 1,714 | 38,571 | 26,449 | 22,565 | 330 | 22,235 | 1.46 | 98.54 |

| Oletzko (Olecko) | 841.3 | 38,536 | 12,398 | 24,562 | 95 | 1,481 | 40,259 | 32.010 | 28,627 | 2 | 28,625 | 0.01 | 99.99 |

| Olsztyn (City) (Olsztyn) | 51.5 | 33,077 | 2,348 | 29,344 | 51 | 1,334 | 34,731 | 20,160 | 17,084 | 342 | 16,742 | 2.00 | 97.99 |

| Allenstein (district) (Olsztyn) | 1,304.7 | 57,919 | 33,286 | 22,825 | 15th | 1,793 | 57,518 | 41,586 | 36,578 | 4,871 | 31,707 | 13.47 | 86.53 |

| Osterode ( Ostróda ) | 1,550.7 | 74,666 | 28,825 | 43,508 | 46 | 2,287 | 76,258 | 54,256 | 47,399 | 1,031 | 46,368 | 2.19 | 97.81 |

| Rößel ( Reszel ) | 855.4 | 50,472 | 6,560 | 43,189 | 0 | 723 | 49,658 | 39,738 | 36.006 | 758 | 35,248 | 2.10 | 97.90 |

| Ortelsburg ( Szczytno ) | 1,705.1 | 69,635 | 46.903 | 20,218 | 47 | 2,467 | 73.719 | 56,389 | 48,704 | 497 | 48.207 | 1.49 | 98.51 |

| All in all | 12,304.5 | 555.196 | 245.031 | 288.790 | 1,177 | 20.198 | 577.001 | 422.067 | 371.083 | 7,924 | 363.159 | 2.13 | 97.86 |

Formally, the voting area was handed over to the district president of Allenstein ( Matthias von Oppen ) on August 16, 1920 by the Inter-Allied Commission in the presence of the Reich Commissioner for the voting area ( Wilhelm Freiherr von Gayl ) .

Voting area Marienwerder

Of the 121,176 eligible voters, 84.00% took part in the vote. Of these, 96,895 (86.52%) voted for East Prussia / Germany and 7,947 (7.58%) to join Poland.

| circle | Area (km²) |

Population (1910) |

Languages 1910 (number of speakers) | Population (Oct 8, 1919) |

voting justified |

Valid votes | Votes in percent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polish | German | other language |

German and another |

all in all | for Poland |

for Germany |

for Poland |

for Germany |

|||||

| Marienwerder (Kwidzyn) | 555.8 | 41,153 | 3,371 | 37.209 | 15th | 558 | 40,730 | 31,913 | 27,387 | 1,779 | 25,608 | 6.50 | 93.50 |

| Marienburg (Malbork) | 216.0 | 29.004 | 693 | 27,968 | 23 | 320 | 27,858 | 20,342 | 17,996 | 191 | 17,805 | 1.06 | 98.94 |

| Rosenberg (Susz) | 1,041.6 | 54,550 | 3,429 | 50.194 | 46 | 881 | 56,057 | 39,630 | 34,571 | 1,073 | 33,498 | 3.10 | 96.90 |

| Stuhm (Sztum) | 641.6 | 36,527 | 15,548 | 20,923 | 33 | 23 | 39,538 | 29,291 | 24,888 | 4,904 | 19,984 | 19.70 | 80.30 |

| All in all | 2,455.0 | 161.234 | 23,041 | 136.294 | 117 | 1,782 | 164.183 | 121.176 | 104,842 | 7,947 | 96,895 | 7.58 | 92.42 |

Commemoration

To commemorate the vote, memorial stones were erected in numerous villages and towns. In 1922 a voting memorial was inaugurated at Marienburg and in 1928 a central voting memorial was inaugurated in Olsztyn . Sports and folk festivals were organized to mark the anniversaries of the voting, for example a relay race through the voting area from Olsztyn in 1925. After the expulsion of the Germans, the Olsztyn monument was destroyed by the Polish administration in 1945.

Web links

- Referendums in East Prussia

- Voting areas in Germany

- Referendums in Germany

- In the days before the referendum in 1920 - reports from the Ermländische Zeitung. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Adolf Eichler (until 1925 General Manager of the Olsztyn Home Service): What was achieved by the home clubs in the East Prussian voting area. 2020, accessed May 10, 2020.

literature

- Rüdiger Döhler : East Prussia after the First World War . Einst und Jetzt, Vol. 54 (2009), pp. 219-235.

- Wilhelm Freiherr von Gayl : East Prussia under foreign flags - A book of memories of the East Prussian referendum of July 11, 1920 , 1940.

- Walther Hubatsch : The referendum in East and West Prussia in 1920 - a democratic commitment to Germany . Hamburg 1980.

- Ernst Weichbrodt: Self-determination for all Germans. 1920/1980. Our yes to Germany. On the 60th anniversary of the referendum in East and West Prussia on July 11, 1920 . Landsmannschaft East Prussia, Hamburg 1980.

- Max Worgitzki , Adolf Eichler, W. Frhr. von Gayl: History of the vote in East Prussia: The fight for Ermland u. Masuria . Leipzig 1921.

- Michael Bulitta: A contribution to the organization of the referendum in 1920 in the Allenstein district (East Prussia). Old Prussian Gender Studies, NF 54, 2006, pp. 191–212.

- Paul Hoffmann: The referendum in West Prussia on July 11, 1920. Comparative presentation of the voting results based on the official material. Marienwerder 1920.

- Bernhart Jähnig (Hrsg.): The referendum in 1920 - requirements, course and consequences. NG Elwert Verlag, Marburg 2002.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Wojciech Wrzesiński: The right to self-determination or the consolidation of state sovereignty. The East Prussian plebiscites in 1920 . In: Bernhart Jähnig (Hrsg.): The referendum 1920 - requirements, course and consequences . NG Elwert, Marburg 2002, ISBN 3-7708-1226-3 , p. 11 ff .

- ^ Robert Kempa: The northeastern part of Masuria in the plebiscite 1920 . In: Bernhart Jähnig (Hrsg.): The referendum 1920 - requirements, course and consequences . NG Elwert, Marburg 2002, ISBN 3-7708-1226-3 , p. 149 ff .

- ^ Law on the Peace Agreement between Germany and the Allied and Associated Powers. In: Herder Institute (ed.): Documents and materials on East Central European history. Topic module "Second Polish Republic", edit. by Heidi Hein-Kircher (accessed April 25, 2014).

- ↑ a b Hans-Werner Rautenberg: The mood of the population in the Masurian voting area . In: Bernhart Jähnig (Hrsg.): The referendum 1920 - requirements, course and consequences . NG Elwert, Marburg 2002, ISBN 3-7708-1226-3 , p. 27 ff .

- ^ A b c Robert Kempa: Youth in East Prussia.

- ^ Andreas Kossert: Masuria, East Prussia's forgotten south. Pantheon, 2006, p. 247.

- ↑ AHF -Information No. 54: The referendum 1920 - Requirements, course and its consequences ( Memento from February 10, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Andreas Kossert: Prussia, Germans or Poles? The Masurians in the field of tension of ethnic nationalism 1870–1956 . Ed .: German Historical Institute Warsaw . Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2001, ISBN 3-447-04415-2 , p. 151 .

- ↑ Stolper Heimatblatt , Volume XIV, No. 8 - Lübeck, August 1961.

- ↑ Hans Ulrich Wehler: Hot spots of the Empire: 1871-1918. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1979, p. 264.

- ^ Preussische Allgemeine Zeitung : The Allies take over , episode 27-10 of July 10, 2010

- ↑ Rocznik statystyki Rzczypospolitej Polskiej / Annuaire statistique de la République Polonaise 1 (1920/22), part 2 . Warsaw 1923, p. 358 (Polish, French, pdf (reproduction at the Herder Institute Marburg) ).

- ↑ The areas ceded by Prussia with a general overview, a municipality and place directory of the districts divided by the new state border, etc. together with area sizes and population numbers (including the Saar area remaining under Prussian sovereignty) . Edited by the Prussian State Statistical Office. Berlin 1922.

- ↑ Preliminary results of the census in the German Reich of June 16, 1925 . In: Statistisches Reichsamt (Hrsg.): Special issues on economy and statistics . tape 5 , no. 2 . Reimar Hobbing Publishing House , 1925 ( pdf ).

- ^ The results of the referendums in West and East Prussia and in Silesia established by the Versailles Treaty. In: Herder Institute (ed.): Documents and materials on East Central European history. Topic module "Second Polish Republic", edit. by Heidi Hein-Kircher (accessed April 25, 2014).

- ^ Hermann Pölking: East Prussia: Biography of a Province. Berlin 2012, pp. 444–445.

- ↑ Robert Traba: "We remain German" - The vote in 1920 as a symbol of identity for the German population in East Prussia . In: Bernhart Jähnig (Hrsg.): The referendum 1920 - requirements, course and consequences . NG Elwert, Marburg 2002, ISBN 3-7708-1226-3 , p. 163 ff .