African trypanosomiasis

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| B56.0 | Trypanosomiasis gambiensis |

| B56.1 | Trypanosomiasis rhodesiensis |

| B56.9 | African trypanosomiasis, unspecified |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

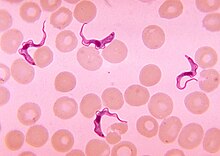

The African trypanosomiasis is a by subtypes of brucei Trypanosoma triggered tropical disease , also called the (African) sleeping sickness is called. It occurs in the tropical areas of Africa and is transmitted by the tsetse fly . The disease, a chronic protozoal disease, has three stages: a few weeks after infection , there is fever , chills , edema , swelling of the lymph nodes, as well as rash and itching. In the second stage, after a few months, symptoms of the nervous system are in the foreground: confusion, coordination and sleep disorders as well as seizures . In the final stage, the patient falls into a sleepy twilight state ( drowsiness ), which gave the disease its name. The pathogen is detected microscopically in the blood or the cerebrospinal fluid and with immunological methods. There are several active ingredients available for treatment.

Pathogen

Sleeping sickness is pathogenic protozoa ( protozoa ) from the group of trypanosomes caused. There are two types of pathogen:

- Trypanosoma brucei gambiense (causative agent of West African sleeping sickness)

- Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (causative agent of East African sleeping sickness)

The genome of Trypanosoma brucei was sequenced in 2005 .

transmission

Humans, cattle and antelopes serve as pathogen reservoirs for the trypanosomes . Unlike malaria , the carriers of sleeping sickness are diurnal, stinging and blood-sucking tsetse flies . In tropical Africa they are mainly found in wetlands (rivers, swamps), but also in dry savannah landscapes (e.g. Kalahari ). The sting is very painful and can be done through clothing. The pathogens enter the sting canal with the fly saliva. It is secreted by the fly to prevent clotting processes. Several thousand pathogens are transmitted through one bite. A single transferred trypanosome could be enough to trigger the disease. Braking and biting flies could (in special cases) possibly play a role through mechanical transmission.

Risk of infection

Not all tsetse flies are trypanosome carriers, so not every bite inevitably leads to an infection. The risk of infection from a bite varies greatly from region to region and is on average in the order of 1%, because the infection rate of the tsetse also varies greatly. So the risk increases with the number of stings. The infection mainly affects the local population, less often tourists.

Epidemiology

Sleeping sickness occurs with a regional distribution pattern that is difficult to determine in the entire tropical belt of Africa. According to WHO estimates, sleeping sickness affects more than 500,000 people. Due to the unstable political situation in many regions and the resulting refugee movements , the disease rate has increased in recent years.

The parasite reservoir of T. b. According to Dönges (1988), gambiense mainly consists of infected, possibly only latently infected people, some domestic animals, especially domestic pigs (also in Desowitz (1981) ) and the giant hamster rat Cricetomys gambianus ( long-tailed mice ). Piekarski (1962) names the antelope among wild animals. Often T. b. gambiense is not diagnosed in humans during the 1st stage and the second stage, which is more difficult to treat, follows (often only after years).

T. b. rhodesiense was found most frequently in the Schirrantilope , followed by the domestic cattle , the hartebeest , the African buffalo , the spotted hyena and the lion ( Dönges ). To a more limited extent than in T. b. gambiense , the sick person is a reservoir of pathogens here too. Piekarski mentions goats and sheep for both trypanosome subspecies .

Which animal species play the most important role in the transmission to humans has not been conclusively clarified, as a complex network of other epidemiological parameters has to be considered (e.g. 31 tsetse species with preferences for certain host animals, as well as rainy seasons, social factors, different pathogen strains etc.). The risk of infection is therefore very different locally and regionally. The parasite reservoirs are to a large extent also relevant for those trypanosomes which cause the so-called nagana in African domestic and farm animals .

Symptoms

The course of the disease depends on the causative agent. If infected with Trypanosoma brucei gambiense , the course of the disease is slower; if infected with Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense , it is usually faster and more pronounced.

Stage I (hemolymphatic phase): Completely without symptoms, the trypanosomes penetrate the parenchymal cells of the brain from the blood after just a few hours. In the first week after infection, a painful swelling with a central vesicle, the so-called trypanosome chancre , can occur at the injection site . However, this symptom only occurs in a fraction of those infected (5–20%). 1-3 weeks after infection begins the actual parasitemia that of fever, chills, headache and body aches, edema, itching, rash and swollen lymph nodes is accompanied. Often this lymph node swelling occurs on the back of the cervical lymph nodes or on the neck and is then referred to as the Winterbottom sign . In addition, there are anemia and thrombocytopenia , as well as increased immunoglobulin levels.

Stage II (meningoencephalitic phase): Approx. 4–6 months after infection (with T. b. Rhodesiense often after a few weeks) the first symptoms of penetration into the central nervous system appear . The patients suffer from increasing states of confusion, coordination and sleep disorders, seizures , apathy and weight loss. It can extrapyramidal disorder or Parkinson's disease -like disease occur.

In the terminal stages, patients fall into a continuous twilight state that gave the disease its name. Cell proliferation ( pleocytosis ) can be detected in the cerebrospinal fluid . The disease is fatal after months to years.

Immune response

The trypanosomes are surrounded by glycoproteins , the so-called “ variable surface glycoproteins ” (VSGs). The VSGs are constantly varied by the unicellular organisms as part of their reproduction, which means that they escape the host's immune response ( antigen variation ). The trypanosome genome encodes over 1000 different VSG genes that are alternately expressed . Although the human immune system can produce antibodies against the predominant antigens, it can only eliminate some of the pathogens because new variants are already circulating in the bloodstream.

Another defense method discovered by scientists from the TU Darmstadt and the Max Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self-Organization is the absorption of the antibodies by the pathogen by means of a flow dynamic feature. The trypanosomes move at high speed in the bloodstream and direct the antibodies to the rear cell pole, where they are absorbed by endocytosis , broken down and thus deprived of their effectiveness.

Diagnosis

In stage I, the pathogens are detected microscopically in the blood (“ thick drop ”), in the puncture of the chancre, in the bone marrow aspirate or by means of a lymph node biopsy. To exclude stage II, if parasites are detected, the cerebrospinal fluid is also examined. ELISA , IFT and PHA / IHA are used as immunodiagnostic methods . Especially with the T. b. gambiense in the late stage, the pathogen detection in the blood may fail.

prevention

At the moment, neither drug prophylaxis for sleeping sickness nor preventive vaccination is available. In the middle of the last century, pentamidine , intramuscularly injected , successfully used as prophylaxis. This was effective for at least six months ( T. b. Gambiense ). The only possible prevention today is avoiding insect bites. Tourists should protect themselves with repellents , mosquito nets, and long-sleeved clothing. It could also be important to wear light-colored clothing, as the tsetse fly is particularly attracted to blue and black. However, these measures are only partially successful, as tsetse flies act aggressively and quickly find an unprotected place on the body.

therapy

Due to the toxicity of the drugs available, sleeping sickness is treated as an inpatient in most cases. In stage II, arsenic compounds are used, which trigger pronounced side effects. The lethality here can be up to 10%.

- Stage I: administration of suramin ( T. b. Rhodesiense / gambiense ) or pentamidine ( T. b. Gambiense ). Both drugs have no effect on pathogens in the central nervous system because they do not cross the blood-brain barrier .

- Stage II: Administration of melarsoprol or eflornithine , previously also tryparsamide ( T. b. Gambiense ). Both drugs work against pathogens in the central nervous system, but are neurotoxic .

In November 2018, a drug with the active ingredient fexinidazole was recommended for approval in Europe , which can be taken as a tablet and cures patients in both stages within ten days. The active ingredient had previously been successfully tested on 750 patients in Africa.

history

David Bruce was one of the first to research the epidemiology of the disease in Africa.

The pathogen ( Trypanosoma gambiense ) was discovered by RM Forde and JE Dutton in 1901.

Based on the work of Harold Wolferstan Thomas and Anton Breinl , Robert Koch researched the effect of Atoxyl against the disease. From this, Paul Ehrlich developed arsphenamine , which was first tested by Werner von Raven in Togo . Before the discovery of antibiotics, the arsenic-containing drug stovarsolan was used as a preventive chemotherapeutic agent .

The first effective drug against sleeping sickness is suramin ( Germanin , Bayer 205 ) developed by Bayer around the 1920s , which was also used for propaganda purposes in Germany at the time of National Socialism .

See also

literature

- Sarah Ehlers: Europe and Sleeping Sickness. Colonial disease control, European identities and modern medicine 1890–1950 . Göttingen 2019, ISBN 978-3-525-31068-7 .

- Peter GE Kennedy: Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). In: The Lancet Neurology . 12, 2013, pp. 186-194. doi: 10.1016 / S1474-4422 (12) 70296-X

- Stefan Winkle : Scourges of mankind - cultural history of epidemics. 3. Edition. Artemis & Winkler Verlag, 2005, ISBN 3-538-07159-4 .

Web links

- African trypanosomiasis. In: Orphanet (Rare Disease Database).

- WHO factsheet

- Information on sleeping sickness from Doctors Without Borders

- Information of the CDC (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ M. Berriman et al. a .: The genome of the African trypanosome Trypanosoma brucei. In: Science. 2005 Jul 15; 309 (5733), pp. 416-422. PMID 16020726

- ↑ T. Cherenet et al. a .: Seasonal prevalence of bovine trypanosomosis in a tsetse-infested zone and a tsetse-free zone of the Amhara Region, north-west Ethiopia. In: Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2004 Dec; 71 (4), pp. 307-312. PMID 15732457 .

- ↑ C. Moll-Merks, H. Werner, J. Donges: Suitability of in-vitro xenodiagnosis: development of Trypanosoma cruzi in Triatoma infestans depending on larval stage of bugs and number of trypomastigotes taken during in-vitro blood meal. In: Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg [A]. 1988 Mar; 268 (1), pp. 74-82. PMID 3134769

- ↑ U. Frevert, A. Movila et al. a .: Early invasion of brain parenchyma by african trypanosomes. In: PloS one. Volume 7, number 8, 2012, p. E43913. doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0043913 . PMID 22952808 . PMC 3432051 (free full text).

- ↑ M. Engstler, T. Pfohl, S. Herminghaus, M. Boshart, G. Wiegertjes, N. Heddergott, P. Overath: Hydrodynamic flow-mediated protein sorting on the cell surface of trypanosomes. In: Cell. Volume 131, Number 3, November 2007, pp. 505-515, doi: 10.1016 / j.cell.2007.08.046 , PMID 17981118 .

- ↑ CHMP recommends first oral-only treatment for sleeping sickness | European Medicines Agency. Retrieved November 23, 2018 .

- ↑ Celine Müller: First oral therapy for sleeping sickness. In: Deutsche Apotheker Zeitung. November 19, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2018 .

- ↑ Donald G. McNeil Jr .: Rapid Cure Approved for Sleeping Sickness, a Horrific Illness. In: New York Times. November 16, 2018, accessed November 20, 2018 .

- ↑ Werner Köhler : Infectious diseases. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 667-671; here: p. 671.

- ↑ JL Kritschewsky, KA Friede: The chemoprophylaxis of relapsing fever and trypanosomal diseases through the stovarsolan. Leipzig 1925.

- ^ Eva Anne Jacobi: The sleeping sickness drug Germanin as a propaganda instrument: Reception in literature and film at the time of National Socialism. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 29, 2010, pp. 43-72.