Alexander I (Bulgaria)

Alexander I (born April 5, 1857 in Verona , † November 17, 1893 in Graz ), born as Prince Alexander Josef von Battenberg, was elected Prince of Bulgaria from 1879 to 1886 .

Life

Alexander Joseph von Battenberg was born as the second son of Prince Alexander von Hessen-Darmstadt and Countess Julia von Hauke , a former lady-in-waiting of his aunt, the Russian Tsarina Maria Alexandrovna . His parents' marriage was morganatic . His mother therefore received from her brother-in-law, Grand Duke Ludwig III. von Hessen-Darmstadt , the title of Countess, later that of Princess von Battenberg . Like his brothers, Alexander held the title of Prince of Battenberg until 1889. As a teenager he was a student at the Ludwig-Georgs-Gymnasium in Darmstadt. Alexander joined the Grand Ducal Hessian Dragoon Regiment No. 24 as a lieutenant . In 1877 he took part in the Russian-Ottoman War of 1877/78 in Bulgaria at the headquarters of Grand Duke Nicholas . Soon afterwards he was transferred to the Garde du Corps in Berlin .

Prince of Bulgaria

As a result of the Berlin Congress , the autonomous Principality of Bulgaria emerged as part of the Ottoman Empire. Alexander's participation in the campaign against the Turks and his close relatives with the Tsar Alexander II of Russia, whose nephew he was, predestined him to head the new principality. Alexander was unanimously elected prince by the Bulgarian National Assembly on April 29, 1879. On July 8th, he entered Tarnowo and swore the oath on the new constitution of the principality, but set up his residence in Sofia .

Since the Chamber of Deputies, dominated by radical agitators, placed obstacles in the way of his efforts for the public good and reduced his power to a shadow, he declared in a proclamation of May 9, 1881 that he would have to lay down the crown if he were not granted extraordinary government powers. On the same day, Alexander I carried out a coup, overthrowing the Liberal government and invalidating the constitution .

However, his regime of powers failed, and just two years later he was forced to reinstate the constitution. This had serious domestic and foreign policy consequences. He lost prestige among the Bulgarians because of his attitude towards the national constitution, and Russia completely stopped cooperation.

At first he opposed plans that aimed at the liberation of further parts of the country that were still under the rule of the Turkish sultan (Macedonia and Eastern Rumelia ), and that aimed at a merger of all Bulgarian areas, such as an organization based on the model of the Internal Revolutionary Organization represented the Bulgarian Secret Central Revolutionary Committee , BGZRK for short (Bulgarian "Български таен централен революционен комитет"). Although he secured the approval of Great Britain and Austria-Hungary through diplomatic channels in July and August 1885, he could not prevail against the negative attitude of the Russian court towards a union. However, when this was irreversible, he saw an opportunity to strengthen his reputation among the Bulgarian people again and took the lead of the movement.

Bulgarian crisis

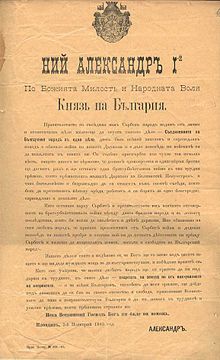

The union of Eastern Rumelia with the Principality of Bulgaria was proclaimed on September 6, 1885. It was one of the greatest events in the history of the young state as well as in the life of the young prince. In this context he is reported to have said: “I am risking my throne and my life, but what should I do? I love Bulgaria! ”After the news of the unification, Prince Alexander issued a manifesto to the Bulgarian people on September 8, officially recognizing the act and calling on the nation to defend the just cause. The next day he drove to the former capital of Eastern Rumelia, Plovdiv , where he was enthusiastically received by the population.

In view of the impending Bulgarian crisis , Alexander sent personal letters to the Austrian Emperor, the Russian Tsar, the Turkish Sultan and Great Britain with a request to recognize the association. He also entered into direct diplomatic negotiations in order to alleviate the discontent of the Serbian Prince Milan . On November 2nd, however, Serbia officially declared war . While the first Serbian units were crossing the border on the same day, Alexander issued a manifesto calling on the Bulgarian population to “defend the country against the aggressors”, as the Bulgarian army had been moved to the Bulgarian-Turkish border because one was from expected an attack there.

After the Treaty of Bucharest on March 3, 1886, the Russian Tsar Alexander III refused . To recognize Prince Alexander I as ruler of enlarged Bulgaria. The Ottoman Empire, on the other hand, recognized in the Tophane Treaty the unification and sovereignty of the Bulgarian tsar over eastern Rumelia. Sultan Abdülhamid II officially appointed the Bulgarian prince as governor general of Eastern Rumelia.

Putsch and surrender of the throne

At the beginning of 1886, pro-Russian forces in the port city of Burgas tried to attack Alexander, who wanted to visit the city in the run-up to the first all-Bulgarian parliamentary elections, and kidnap him to Russia. However, the conspiracy was exposed and those involved were arrested. On August 9 , at the instigation of Russia, a group of pro-Russian officers launched a coup against Alexander I and forced him to abdicate. He was then taken to Russia. With the support of the Bulgarian parliamentary president Stefan Stambolow , who organized a counter-coup with the help of the military, Alexander was able to return briefly to the throne of Bulgaria. On September 7, 1886, however, he finally renounced the rule because he no longer enjoyed the trust of the Russian tsar. After long internal political turmoil, Ferdinand I of Saxe-Coburg was elected as his successor .

Marriage and offspring

In 1883 he got engaged to Princess Viktoria of Prussia , called Moretta, daughter of the future Emperor Friedrich III. and his wife Victoria of Great Britain . But their grandfather, Kaiser Wilhelm I , and Prince Bismarck were against the engagement for political reasons and prohibited marriage. For years Viktoria fought in vain against the ban, but Bismarck in particular opposed it decisively. In 1888 the engagement was finally broken off for reasons of state .

On February 6, 1889, he married the opera singer Johanna Loisinger (1865–1951) in Menton / France . After the marriage, the couple took the name of a Count or Countess von Hartenau and withdrew from the public. Alexander joined the Austro-Hungarian Army and lived with his family in Graz . The marriage had two children:

- Assen Ludwig Alexander, Count of Hartenau (1890–1965)

- Zwetana Marie Therese Vera, Countess von Hartenau (1893–1935)

Death and burial

Count Hartenau, the former Prince of Bulgaria, died unexpectedly after almost five years of marriage in Graz on November 17, 1893. His body was transferred to Sofia and received a state funeral , which was attended by Alexander's widow, the new Bulgarian Prince Ferdinand I and many Bulgarians . After a service in the Sveta Nedelja cathedral , Alexander was buried in the rotunda of St. George .

In 1897 Alexander was reburied in a mausoleum built for him on today's Wassil-Lewski-Boulevard . The Swiss architect Hermann Mayer designed an 11 m high mausoleum on 80 m² in a predominantly neo-baroque style . The interior design comes from the Bulgarian painter Haralampi Tachew .

The mausoleum was not accessible from 1947 to 1991. It was only restored and reopened after the end of the People's Republic of Bulgaria . Today, in addition to a cenotaph , Alexander's private things and documents that his widow made available in 1937 are on display. Johanna Loisinger was buried in Graz in the St. Leonhard cemetery.

See also

literature

- Egon Caesar Conte Corti : Alexander von Battenberg, his fight with the tsars and Bismarck: papers and other unprinted sources left after the first prince of Bulgaria . Seidel, Vienna 1920, DNB 579298744 .

- Leslie Gilbert Pine: The New Extinct Peerage 1884-1971: Containing Extinct, Abeyant, Dormant and Suspended Peerages With Genealogies and Arms . Heraldry Today, London, 1972, ISBN 0900455233 , p. 52.

- Hugh Montgomery-Massingberd: Burke's Royal Families of the World , Volume 1: Europe & Latin America . Burke's Peerage Ltd, London, 1977, ISBN 0850110238 , p. 58.

- Jirí Louda, Michael MacLagan: Lines of Succession: Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe . Little, Brown and Company, London, 2nd edition, 1999, plates 109, 150.

- Hans-Joachim Härtel, Roland Schönfeld: Bulgaria. From the Middle Ages to the present. Regensburg, Friedrich Pustet Verlag, 1998, ISBN 3-7917-1540-2 , pp. 128-138.

- Christo Lukov Matanov: Alexander von Battenberg, Prince of Bulgaria, 150 years since his birth . Exhibition booklet German / Bulgarian 2007.

- Haralampi G. Oroschakoff: The Battenberg Affair: Life and Adventure of Gawril Oroschakoff or A Russian-European History . Berlin-Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 3-8270-0705-4 .

- Alexander Prince of Battenberg. In: Austrian Biographical Lexicon 1815–1950 (ÖBL). Volume 1, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 1957, p. 14.

- Egon Caesar Conte Corti: Alexander von Battenberg. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 1, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1953, ISBN 3-428-00182-6 , p. 191 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Wilhelm Diehl: Alexander von Battenberg . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 45, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1900, pp. 751-756.

- Hartenau, Alexander, Count of . In: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon . 6th edition. Volume 8, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1907, p. 836 .

Web links

- Vladimir Vladimirov: French publishes book about Alexander the Exarch. Radio Bulgaria, April 7, 2005, accessed August 9, 2016 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Iwan Karajotow, Stojan Rajtschewski, Mitko Iwanow: History of the city of Burgas . From Bulgarian, История на Бургас. 2011, ISBN 978-954-92689-1-1 , pp. 180-187.

- ↑ Borislav Gurdew: On the 110th anniversary of Prince Battenberg's death. Retrieved January 1, 2018 (Bulgarian).

- ↑ Mausoleum of Alexander I Battenbarg. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on March 13, 2005 ; Retrieved January 1, 2018 (Bulgarian). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Alexander von Battenberg . Austrian State Archives , exhibition 2008, accessed on August 9, 2016.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Alexander I. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Prince of Battenberg; Battenberg, Alexander Joseph von (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Prince of Bulgaria |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 5, 1857 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Verona |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 17, 1893 |

| Place of death | Graz |